May 30, 2004

K-PUNK RECOMMENDS

Undercurrent returns after a brief hiatus with some typically excellent posts. One on Jacques Tati and the photography of Gursky as practicioners of 'subrealism'; and another which sets k-punk to rights. Actually, that's way too reductive an account of a post which embraces, with grace and eloquence, art, philosophy, blogging, friendship and strategies for living.

(Don't know why I'm recommending Undercurrent really, because I assume that, by now, you're going there automatically.)

But it sure is quiet round here: what with Luke in NZ, Matt Woebot off in Italy, Simon R in the treatment room with an injured thumb (no kidding), and Penman apparently really gone for good this time (but I'll never forget)....

At least Sean is on fine form....

HIP HOP AND THE BLACK ECONOMY

Fascinating piece by Abe (prompted by a great post bySteven Shaviro about Ghostface's new album) on hip hop mixtapes (actually a misnomer, since, as Abe points out, many of the 'tapes' are issued on CD and some involve no mixing whatsoever). Abe argues that many hip hop artists effectively operate in two economies: the legal, white economy, controlled and regulated, and the more vivacious black economy, where samples are used without permission.

May 29, 2004

STOP PRESS

Popjustice is right. The new Girls Aloud single is a treat and a triumph.

Have you heart it yet, Mr Carlin?

NONORGANIC MEMORY

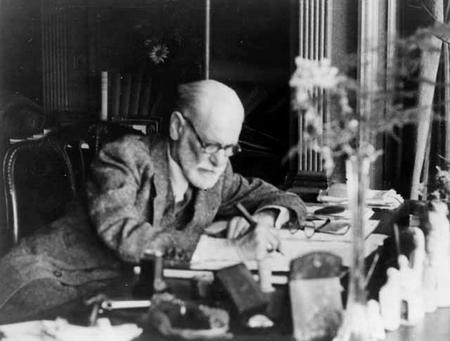

Professor Barker: 'In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud takes a number of crucial initial steps towards mapping the Geocosmic Unconscious as a traumatic megasystem, with life and thought dynamically quantized in terms of anorganic tension, elasticity, or machinic plexion. This requires the anorganizational-materialist retuning of an entire vocabulary: trauma, unconscious, drive, association, (screen-) memory, condensation, regression, displacement, complex, repression, disavowal (e.g. the un- prefix), identity, and person.

Deleuze and Guattari ask: Who does the Earth think it is? It's a matter of consistency. Start with the scientific story, which goes like this: between four point five and four billion years ago - during the Hadean epoch - the earth was kept in a state of superheated molten slag, through the conversion of planetesimal and meteoritic impacts into temperature increase (kinetic to thermic energy). As the solar-system condensed the rate and magnitude of collisions steadily declined, and the terrestrial surface cooled, due to the radiation of heat into space, reinforced by the beginnings of the hydrocycle. During the ensuing - Archaen - epoch the molten core was buried within a crustal shell, producing an insulated reservoir of primal exogeneous trauma, the geocosmic motor of terrestrial transmutation. And that's it. That's plutonics, or neoplutonism. It's all there: anorganic memory, plutonic looping of external collisions into interior content, impersonal trauma as drive-mechanism. The descent into the body of the earth corresponds to a regression through geocosmic time.'

Watching Quatermass and the Pit again last week - Nigel Kneale's masterpiece, and undoubtedly the best film Hammer ever released - I started to think, again, about memory, trauma and the organism.

The film is about an excavation in the fictional London tube station of Hobbs End. Workers uncover what turns out to be a Martian spaceship, filled with the corpses of repulsive quasi-insect beings. Aliens, we think... Yet the genius of Kneale's script is that the Martians turn out not to be aliens at all. Fleeing the destruction of their own planet, the Martians had, five millions years previously, interbred with protohuman hominids in order to perpetuate their species. So the distinction between alien and human is fatally unsettled. As the Quatermass sequence progresses, the alien has become increasingly intimate: The Quatermass Xperiment - the aliens are out in space; Quatermass II - the aliens are already amongst us; Quatermass and the Pit - we are the aliens.

Greil Marcus devotes perhaps the most fascinating and unexpected pages of Lipstick Traces to an analysis of the film, under its US title, Five Million Years to Earth. 'Though there is no consciousness of the intervention,' he wrote,

'there is phylogenetic memory. Freud believed that modern people in some fashion remember, as actual events, the parricides he thought establish human society, and unconsciously preserve that memory in otherwise inexplicably persistent myths and rituals; in Moses and Monotheism he argued that, hundreds of years after the fact, the Israelites carried a memory of their forebears' murder of a first Moses, even though in oral and written tradition the event was completely suppressed. In Five Million Years to Earth the argument is that modern people remember step-parents who, with infinite patience, set out to kill their progeny.'

A darker version of the origin of humanity story told in the near-contemporaneous 2001*, Quatermass and the Pit also shares much with Ballard's The Drowned World: most importantly the theme of what Marcus calls 'phylogenetic memory'.

As I understand it - and I'm really, really keen for someone who knows about science to set me right here (Geeta???) - there is no scientific basis for this notion of 'phylogenetic memory'. Genes are a ROM transmission system; the legacy that you will pass on to your offspring is already determined before your birth (unless you are subject to mutation). Experiences, learning - culture - cannot be directly passed on; such lessons have to be learned anew by each generation.

What then of instincts? How do they fit in? Are instincts a kind of memory?

With Quatermass and the Pit, the memory is a 'literal' memory, a deeply submerged but still accessible mental trace (triggered, in the film, by the unearthing of the spaceship); with The Drowned World, the 'memories' are encoded in they physical form of the human being itself, Ballard's famous 'spinal landscapes.' Quatermass and the Pit is archaeological; The Drowned World, geological. Anticipating Deleuze and Guattari's 'geology of morals' Ballard's innovation lay in collapsing culture, psychology and biology into geology.

Should we refer to Ballard's 'spinal landscapes' as memories at all, or as trauma records? Trauma is anti-memory, non-organic memory, what the organism cannot assimilate but which - according to Freud - makes possible organic life as such. In non-organic systems, there is no distinction between what is remembered and that which remembers; there is no unalterable 'Judgements of God' ROM, just as there is no so 'recording' system that can't itself be 'recorded over'.

Questions, questions...

*Although the Quatermass and the Pit story was, by then, over a decade old. It had been filmed by the BBC back in 1956.

KEEP EM OUT

Scott directs our attention to this anti-BNP thread on ILX.

Only today, I was walking across to the shops when I saw a discarded BNP leaflet on the pavement. In Bromley. Don't know what the political history of this area is, to be honest (nearby Eltham, of course, has an ignominious reputation).

Last week I was walking by Ladbroke Grove station where people were giving out leaflets issued by Ken Livingstone. The point was simple: he was requesting that we exercise our vote, not necessarily for him or for the Labour Party, but for anyone apart from the BNP, because current projections suggest that they will gain enough of a percentage of the vote to gain representation on the London assembly.

Ordinarily I wouldn't vote. Not out of 'apathy', but from principled disengagement. It always seemed to me that the only way to in some small way remove legitimation from Nu-Labour was to increase the non-voter statistic. But Ken's right. It's a duty to keep fascists out. So I'll be voting and I hope everybody else will be too. (BNP supporters excepted, naturally).

May 27, 2004

UPDATE

Janet Street-Porter's infuriating cake and eat it defence of Emin et al on Question Time just now - we should respect YBAs because they are popular AND we should defend them against the derision of the masses. A perfect summation of the confused mixture of populism and elitism that underlies the Britart aesthetic.

Let's hope that the fire acts as a symbolic end to Britart.

BONFIRE OF THE VANITIES

So Jeanette Winterson says that only 'philistines' are celebrating the Saatchi fire. 'The great strength of Brit Art in recent years is that is has forced the debate on what art is and who it is for,' she claims.

Ah, debate. Who was it who said, 'Debate is idiot distraction'?

The sentiments Robin quotes from Deleuze couldn't be more apposite.

"[P]hilosophy has absolutely nothing to do with debate, it’s difficult enough just understanding the problem someone’s framing and how they’re framing it, all you should ever do is explore it, play around with the terms, add something, relate it to something else, never debate it.

Because once one ventures outside what’s familiar and reassuring, once one has to invent new concepts for unknown lands…then thinking becomes, as Foucault puts it, ‘a perilous act,’ a violence whose first victim is oneself."

Or, as Robin himself put it, in connection with I'm a Celebrity Get Me Out of Here: "I have some creeping sense that by being drawn into serious debate about these things one is merely contributing to their reflexive self-image as important cultural beacons. Isn't it a waste of mental energy, for people who have some, to devote it to analysing this stuff?"

The Britart debate, such as it is, was begun and ended with the r.mutt urinal nearly a century ago. Duchamp established once and for all that the object is irrelevant; anything can be a work of art. End of. Or it should have been: instead, we've been subject to ninety years of tedious recapitulation in which the radicality of Duchamp's insight has been garbled. If Duchamp's original gesture was liberatory - 'anything can be art, lose your hang-ups about categorization' - its take-up by his adherents has been relentlessly conservative and restrictive. Now, art can only be 'about art', a boring meta-discourse. The more interesting conclusion to draw from Duchamp's jest was Brian Eno's: that art is less about the object, and everything to do with affect. It is not the art object, but the art experience to which we should pay attention.

But this ability to produce affect shouldn't be confused with the capacity to 'inspire' mindless chit-chat.

A cheap reversal perhaps, but it's Winterson, not the straw men she attacks, who is peddling the worse kind of philistinism. Winterson happily advocates the empty platitude - propagated by Kapital at its most vulgraizing - that art is a kind of PR event. What is important, it seems, is 'that people are talking.' On this definition, art is in nowise different from reality TV.

There's nothing 'perilous' about Emin or Hirst; no hint of 'unknown lands'. The appropriate analogy would be Tarantino; someone who didn't create the taste by which he was judged, but who simply hung onto the coat-tails of previous trailblazers. With the Britartists, as with Tarantino, controversy really means 'controversy': a tried and tested revisting of already exhausted strategies that are just as kneejerk as the response they elicit. Such posturing causes minimum discomfort to the artist, who, in the very moment that they are being vilified (and, naturally, gaining valuable publicity) are already being hailed by self-serving commentators as 'important'.

The point is, worthwhile art may turn out to be controversial, but art that is designed solely with the purpose of producing controversy can never be worthwhile. Winterson's own analogy makes this point consummately. "The informal Constable appreciation society," she writes, "forget that their hero had tomatoes thrown at his pictures, and that they were considered crude daubs by those who complained that Constable did not understand chiaroscuro, and simply laid one primary colour next to another without grading." Unlike the Britart controversocrats, Constable didn't produce his art in order to elicit (yawn!) shock, even if shock, outrage and misunderstandings were by-products of his painting. Constable had what the alleged conceptualists of Britart lack: a unique vision of the world, a set of perceptions that re-engineer the way in which we see. This meant that he could lead taste, pre-empt it; something that the Britartists could never hope to do. It's precisely the 'tomato-throwing' dismissal that has never happened to the cossetted Britartists, who, may well be derided by elements of the public, but who were immediately coddled by a sycophantic art establishment.

All that said, I can't quite go along with Nick Southall or Sean, in part because the fire didn't only consume PoMo tat like Emin and Hirst. There was also serious work by the likes of Paula Rego in there, and the Chapmans categorization as 'Britartists' never seemed to fit. Too much vision, too much affect.

Really excellent piece here on the Nick Berg murder and its exploitation by the American Right. It requires a Kurtz-like unflinching incisiveness to point up the hypocrisy of the 'this proves what savages the muslims are' lobby . Someone brutally executing one person is worse than bombing thousands? How is that exactly?

May 26, 2004

THOUGHTS INSPIRED BY THE CHAMPIONS LEAGUE FINAL

Watching the Champions League Final, it stuck me once again that Jose Mourinho is the most Clough-like manager since the great man himself. It's not only his renowned abrasion and strong will; it's his tactical methods. The discipline and tenacity of Porto's defence tonight, and their capacity for quick, incisive breaks, recalled Clough's Forest teams at their best.

(Of course, the sultry Mourinho is a good deal more dapper and handsome than the raddled Clough ever was.)

All of which is why I predict that, if Mourinho takes on the Chelsea job, it will be a disaster akin to Clough's legendarily ill-starred and brief tenure at Leeds. Like Clough, Mourinho is a master of nurturing young talent and he has made an art out of reconditioning the careers of veterans who, so far as anyone else was concerned, were washed up. Also like Clough, he has limited experience of dealing with pampered playboys accustomed to success. Motivating raw young recruits and those enjoying an improbable Indian Summer in their career is one thing; moulding a disparate group of petulant superstars into a team is another entirely.

Clough was successful at Forest because he was able to dominate the club at every level (much in the way that Ferguson used to be able to preside over United - recent events indicate that this dynasty may be crumbling). As became clear in his press conference yesterday, Mourinho will find himself at odds with everything Roman Abramovich stands for: the (discredited) Real philosophy of headhunting the best-regarded and most expensive players from around the world and then worrying about team-building. Mourinho will simply not be able to rebuild Chelsea in his own image. Much better, if he wants to do that, to go to Liverpool, where he will retain control of transfers, where the biggest players have a homeliness lacking in Chelsea's galaticos and where the fans are hungry for success of any kind.

May 25, 2004

NEW IN FROM MARCUS AT REPHLEX

FRIDAY 18th JUNE

at 'The End'

16a West Central Street, London, WC1

T. 0207 419 9199

(Tottenham Court Road Tube)

11pm - 5am

GRIME ROOM:

KODE 9

DIGITAL MYSTIKS

LOEFAH

DARQWAN

BRAINDANCE ROOM:

DJ REPHLEX RECORDS

ALEKSI PERALA (aka Astrobotnia)

D'ARCANGELO

DMX KREW

CYLOB

May 24, 2004

ALSO IN THE TIMES TODAY

Three separate pieces on Morrissey, including an editorial. That makes him OFFICIALLY an enduring part of the English cultural landscape, doesn't it?

'ONE OF THE LAST REDOUBTS OF UNCHALLENGED ELITISM IN BRITISH SOCIETY.'

Robyn Harris in The Times today with a timely attack on the BBC: 'The licence fee is an unfair, legally enforceable, regressive tax, and it is deeply unpopular... Forget Eton, the Guards and Home Counties golf clubs. Broadcasting is one of the last redoubts of unchallenged elitism in British society.'

You have to take a step back from the licence fee to see how absurd it is. (I'm sure non-UK readers already think it's incomprehensibly ridiculous.) Imagine if Sony were able to charge a levy every time you bought a CD player.

In the days of Potter and the like, the BBC could claim to offer a unique product. Not any more. If the BBC has a USP now, it's drearily 'lavish' costume dramas that I find deeply unappetizing and which I certainly wouldn't pay for given the choice (Trollope! Trollope! Good God). Its contemporary drama, as I have complained here many times, is abject, and you cannot believe that the BBC could ever have commissioned something like The Singing Detective.

Mark Thompson, the new D-G, comes, as everyone knows, from Channel 4. Hmmm, that bodes well doesn't it? C4 is even worse than the BBC; an absolute scandal that totally fails in its public service remit (is anyone even pretending to enforce that any more?), with its endless menu of tedious lifestyle programmes, exploitative reality TV shows and American imports (much the best thing on the channel, obviously), and its boring, pathetic obsession with 'youth'.

It's only genuflection towards tradition, a phlegmatic don't rock the boat attitude and a strange, pre-Thatcherite acceptance of things as they are that leads to people continuing to accept a tax every bit as inequitious as the Poll Tax.

May 19, 2004

HAS IT COME TO THIS?

Jesus Christ!

Did anyone - UK-based obv - see the Green Party Election broadcast tonight or was it some delirium I unwittingly slipped into?

The broadcast was like some Alan Partridge offcut discarded because it was too embarrassing.

Picture the scene. A third on the bill group of Soul II Soul imitators from 1991 strike up what they fondly imagine is 'a soulful groove.' They begin to sing - a chant that it's too traumatic for me to remember, but you can imagine the basic idea, you know fatuous platitudes about 'going green' and 'making a difference.'

Then, then.....

Cut to the leader of the Green party. He's bellowing over the music, declaiming Green policies.

O

my

God

It can't be, it can't be....

Yes ---- what he thinks he's doing is....

rapping....

If this weren't painful enough, later in the broadcast, he starts

dancing

(Nervous system disintegrates in meltdown of vicarious embarrassment).

CUTTING IT VERSUS SEX AND THE CITY

Category: TV trivia

'Why,' I asked her, 'if you like Sex and the City so much don't you like Cutting It?' I suppose I could reverse the question: why do I love Cutting It but detest - in that 'I detest it but watch it' way - SATC?

Superficially, the series have a lot in common. Both are female-orientated, with strong female casts and a predominantly female audience. Both centrally concern relationships, romance and sex. And the central drama in both is strikingly similar: the Big/ Barishnikov/ Carrie love triangle is doubled in Cutting It by the Allie/ Finn/ Gavin relationship.

And yet, in the end, the differences obviously outweigh the points of connection.

Part of this is down to SATC's consumer porn. To the trained eye of the fashionista (i.e. not mine), SATC is so much more sumptuous than the relatively dowdy Cutting It. (This is perhaps reversed by the relative appeal to men of the leading characters in each; as Penman so sagely observed way back when, all of the Sex harridans are repulsive. In the war of the Sarahs, give me Parish over Parker any day of the week!)

Also, and related to this, Cutting It keeps it local whereas SATC flaunts its cosmopolitanism (and its Cosmopolitanism). Cutting It is resolutely local, provincial, whereas SATC was all New York deracinated and internationalist.

And this leads onto the third and most important difference: rootedness. In Cutting It, the theme is the past; its inescapability, the way it will come back to take its revenge upon you, the way you are condemned to repeat it. This was one of the points to emerge from the reverse Great Expectations plot of Gavin's 'outing' this week as the child of a bourgeois family. 'Bullshit', Ruby said, is a 'time bomb'. It will go off in the end, just as roots can only be dyed for so long. By contrast, SATC was all about new starts, about the lack of a past. What do we know of Carrie, Samantha et al's early - presumably pre-NYC - lives? What we do know of their parents? In SATC, family history is excised as neatly as split ends, cut off and swept away, whereas in Cutting It, family history, with all its shadows, secrets, compromises, comforts and commitments, is the net (at once supportive and constricting) that all the characters must negotiate. (Even if the family is not genetic; one of the other themes of this week's episode). In SATC, the problem was: do I start a family or not? In Cutting It, the problem is belonging to a family.

It's impossible not to see this as an English versus an American thing. America, with a future but no past; England, with a past and no future. America, brimming over with possibility, where the sheer blankness of the future, the superfluity of territory, the excess of options are the issue ('how can I possibly choose?'). The terror in SATC was hence of closing down possibilities, of acquiring a past. In Cutting It, the fear (cf Darcy's terror that her life might have been fixed and set before her birth) is of never being able to leave the past ('there is no choice').

SPAWN OF SATAN

Followed the link from Tom at Brown Wedge to this bizarre site on C. S. Lewis as the spawn of Satan.

"Clive Staples Lewis has been perhaps the single most useful tool of Satan since his appearance in the Christian community sometime around World War II."

The page of Letters from Readers ('The Evil Fruits of C. S. Lewis') is especially, creepily compelling. Check the way they refute the reasonable assertions of correspondents saying, like, perhaps they could be more careful in their scholarship... A window onto a truly terrifying world. (Check the home page...)

May 17, 2004

BEYOND THE HORIZON

Baudrillard: "there is no longer a double, one is already in the other world, which is no longer an other, without a mirror, without a projection, or a utopia that can reflect it - simulation is insuperable, unsurpassable, dull and flat, without exteriority - we will no longer even pass through to ‘the other side of the mirror,’ that was still the golden age of transcendence.”

Angus on The Truman Show.

Angus suggests that the film would have been much better if it was all from Truman's POV and all the 'media studies bollocks' were cut out. He quite rightly points out that there has never been a reality TV show in which the participant didn't know that they were in a television programme (although, of course, there have been shows in which the people involved didn't know what type of reality show they were on - Joe Millionaire for instance). The film was obviously an extrapolation of current trends, though as Angus says, the Truman experiment surely goes so far beyond any acceptable limits that any satirical intent is stymied. (I have wondered for some time, however, how long it would be before there were 24 hour soaps...)

As with The Matrix the problem with The Truman Show is that it assumes too straightforward an opposition between 'the real' and 'the illusory'. It's what people who haven't read Baudrillard think Baudrillard is all about. But what Baudrillard tirelessly insisted upon was the way in which the hyperreal had invaded and superceded the real. The very ambivalence of the 'reality' in 'reality TV' demonstrates this. No one really imagines that this 'reality' is some unmediated primal authenticity unaffected by televisualization. In some ways, Truman is the only person who lives in 'reality', the 'true man'; the rest of us are condemned to endure hyperreality.

But I always read The Truman Show as in part a religious allegory. The Ed Harris character was clearly God, presiding over a preordained, perfectly secure universe whose smallest details he has lovingly designed. What Truman must choose between this theistic cosmos (determinism) and a Sartrean existentialist universe (free will). The door on the horizon, the door opening onto blackness, the blackness of pure potentiality, the void of existentialist subjectivity, is the threshold between these two realms.

Nietzsche: "But how did we do this?

How could we drink up the sea?

Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon?

What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun?

Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving?

Away from all suns?

Are we not plunging continually?

Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions?"

ONE YEAR LATER....

K-PUNK IS ONE YEAR OLD!

And here's the first post to prove it...

Well, a year and a bit, actually, since I'm such a dope that I missed the actual anniversary...

Contrary to the plague of miserabilism that seems to have descended on blogdom (as identified by Robin), I know EXACTLY why I blog...

For much of the last year, especially when things got REALLY BAD, it's been my only connection to the world, my only outside line....

It's reinvigorated my enthusiasm for so many things, and pricked my enthusiasm for things I'd never previously considered.... (I say this especially to the currently disenchanted Marcello, who has done both; I remember being drawn out of a catatonic depression last year by reading through the entire Church of Me archives.)

It's made me many valued friends, both online and (thanks to Luke's brilliant walks) off too... Plus it's put me back in touch with friends I'd lost contact with. (Yeh, there's the occasional wanker, but I can honestly say, very few, almost none really, certainly there's far fewer of them than the excellent, high quality correspondents.)

In short, and no exaggeration, it's made life worth living...

I know it's an awful cliche, but it's really true, a blog is what you make it...

So heartfelt thanks to all of those who have contributed, by linking, commenting, reading or inspiring...

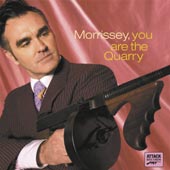

MORRISSEY AGAIN

Geeta responds with a well-reasoned piece on Morrissey. I haven't heard You are the Quarry but I'd trust Geeta's opinion of it over the 'return to form' consensus that seems to be coalescing in most other quarters. I write as someone who admired and appreciated The Smiths, not as an in any sense an obsessive. (The Smiths don't exactly fit squarely into the k-punk aesthetic, for reasons that are readily apparent. This from way back more or less summarises my views on the Moz.) But yes, my current appreciation of Morrissey is based on his music not at all and entirely on his persona. I would question, though, whether Morrissey's album is any worse than that by such feted luminaries as Franz Ferdinand (whose dull sludge was hailed, incredibly, as 'revolutionary' on the front of that Word magazine, I noticed), or Keane, or The Coral. Morrissey isn't the problem; the fact that the paucity of contemporary indie makes us still need him, that's the problem.

May 16, 2004

ostentatious absenteeism

I disagree with Geeta and, as ever, find myself echoing Robin. By his presence alone, Morrissey on Jonathan Ross showed up Now Pop's inability to produce (self-made) mythical characters. Or is that absence? As Simon pointed out back in the day, Morrissey developed a kind of 'ostentatious absenteeism', a perverse 'look at me, I don't want to be here' form of attention-seeking/ repulsion.

On JR he still, absolutely, refused to play the game, refused to step out of role, to relax into Ross's PoMo spree of meta-commentary and lampoonery. Unlike Robin, I do like Ross (he can be forgiven most anything for his wit and his enthusiasm) but he was clearly out of his depth with Morrissey whose gravity and implacable seriousness were unassailable. Both men seemed uncomforable, though Morrissey, painting himself as the misanthrope of legend, on the edge of his nerves (where you suspect he lives most of his life), coiled, reflective, cultivating hatreds and amours fou alike, was at least more used to this painful level of social embarrasment. (Ross's joke about Morrissey becoming his friend quickly shaded into Alan Partridge territory: 'When are you coming round? ... I've got two lambs...')

His solo career amounts to very little, of course, although the new single is compelling enough, and 'The More You Ignore Me, the Closer I Get' is an underrated masterpiece, every bit the equal of his best work with The Smiths, an unflinching vignette of obsessive fixation ('I bear more grudges/ than lonely high court judges'). And his playing of 'Every Day is Like Sunday' reminded you that it is one of THE high watermark moments in Britannia Moribundia ('Trudging slowly over wet sand.... Win yourself a cheap tray'). Its perversity, its Betjeman 'Slough'-esque rage and disgust ('Come armageddon come....') tempered by a grim fascination, a Dubliners-like inertial pull; the o-so English attachment towards that which is ostensibly loathed. (The Joyce comparsion actually an interesting one, since both would remain permanently attached to a homeland they'd eventually live outside of.)

Robin talks of Lynch and that's strangely right: Morrissey in L.A. must be like one of Lynch's ghostly chanteurs, existing in some Lynchian untime, neither of the present nor of the past, never really rock and roll.... I suppose the closest parallel would be Ben, the Dean Stockwell character from Blue Velvet; performer for all those rough trade gangster-types (or perhaps that is Morrissey's dream of what he could be)....

As I watched, I realised that I couldn't remember the last time I'd seen Moz interviewed on television. (Well, it's been, so they said, eighteen years...) Is it me or does he look more handsome than before, his eyes an even brighter, an even steelier, blue than ever? That East End gangster look suits him rather well, I think.

The strange power of media and pop to simulate intimacy....

Morrissey says he doesn't like people, but we all feel, secretly, that he'd like us, don't we?

BOYS KEEP SPINNING

Obviously Piers Morgan had to go, but reflect on this: as Alex Salmond sagely pointed out on Question Time on Thursday, the only people to be sacked (or forced to resign) over Iraq have been in the media (Morgan, Gilligan, the DG and Chairman of the BBC). And the QLR's high-handed tone shouldn't make us forget that some of their personnel are being investigated for murdering, not 'merely' torturing, a prisoner.

May 14, 2004

YOU'VE GOT THE BODY

Lies/ More Lies - Beckett and Taylor

Snakeskin Teeth/ Abusing the Body - Spandex

This blogging lark's OK when you get free stuff as good as this.

An upcoming release on the Hand on the Plow label.

The opener, 'Lies' by Beckett and Taylor (I echo Philip's entreaty that these guys please get a less delibidinizing monniker; Beckett and Taylor sound like a firm of provinicial solicitors), is a kind of digital blues: an unplaceable and displacing suturing of house, funk, plantation chant and glitch that gratifyingly refuses to airbrush out the stitchmarks. 'More Lies' attenuates the vocal to vowel-stabs (o's and i's) and distributes it over a more driving house beat.

But the stand-outs here are the two tracks by Spandex (which is, if possible, an even worse name than Beckett and Taylor). The desire-drunk-funk of 'Snakeskin Teeth' boasts a gloriously, deliriously stoned vocal that recalls Arthur Russell at his wooziest or an even more slurred John Martyn. It's like the Junior Boys if their reference points were house and blues rather than 2-step and OMD. As the track develops, it's as if the vocals simultaneously become increasingly intoxicated and increasingly artificialized (as the lines - scarcely coherent at the start - become wreathed in delay and thick digital fog, and the voice devolves into tics and stammers) until, by the end, it sounds like it's being sung by a drunken cyborg.

Not surprsingly, one of the tracks of the year for me so far, no contest.

If 'Snakeskin Teeth' has the majestic torpor of a supine body reclining into satiation, 'Abusing the Body' (whose title has an unfortunate topical piquancy en ce moment) is all datapaniked confusion and stuttering anxiety, a chatterspasm of digitally-agitated vocal and hesitant beats. The track's hook is a sample that, when, initially, it's submerged in the mix and abbreviated to the briefest of stabs, registers only as a shiver of deja vudu, the merest subliminal sliver. As the track progresses, the suspicion that there's something familiar here hardens into recognition when the line 'You've got the body....' from Hall and Oates' epochal 'Say No Go' emerges from the digital mist.

May 13, 2004

Simon cites Jon on the inability to consume EVERYTHING. Put me in mind of this and also Siobhan's riff on flitting.

May 12, 2004

The Atrocity Exhibition

"War strips us of the later accretions of civilization and lays bare the primal man in each of us. It compels us once more to be heroes who cannot believe in their own death; it stamps strangers as enemies, whose death is to be brought about or desired; it tells us to disregard the death of those we love."

- Freud

I'm not going to make a habit of this, I promise ---- but here's a political post ----

Perhaps the most amazing aspect of the latest events in Iraq is that they reveal the extent to which American incursion has actually undermined US interests. Now this is surprising, since Leftist criticism of the Iraq war has assumed that the war was prosecuted to pursue American self-interest rather than out of some high minded ethical principle. The neo-conservative defence of the war has not disagreed; it has simply maintained that American interests are coincident with the best interests of humanity. Using a version of 'invisible hand' logic, neo-cons have argued that, in protecting their own interests, the Americans will produce a better world for everyone. Apologists for neo-con nutters like Wolfowitz like to present them as post-ideological pragmatists, single-minded in their protection of American interests.

But who really imagines that America and Americans are safer now than in the time before the war? Far from coolly driving through a program that will secure US interests, the American strategy in Iraq seems to have been guided by a strange death drive: an almost systematic will to make things worse for themselves. The Americans have now succeeded in transforming a secular state into a seething hotbed of Islamist extremism. On the Arab 'street', the abuse scandal has confirmed the lowest and most hyperbolically negative view of the decadance and barbarism of Western society. None of the lessons that the British learned in Kenya or Northern Ireland - that interning actually feeds local militicancy - have been heeded. And a correspondent in today's Independent speculates that the inevitable and ignominious departure of America from Iraq could presage not only a civil war in that country which will destabilise the entire region, but which could effectively end the States' influence on the Middle East.

Only a death drive could account for the American actions in setting up an interrogation centre in Saddam's former headquarters of torture: an act of such stupefying guilelessness and stupidity that it beggars belief. As someone observed: would the Americans in postwar Germany have set up a Nazi interrogation unit in Auschwitz? The symbolic power of the Americans installing themselves in the of Saddam's regime need hardly be underlined.

Oh, and I've just clocked onto this baffling media euphemism, 'contractor'. I'd previously naively imagined that 'contractor' meant a builder or something, when of course it means 'mercenary'.

"'In terms of television and the news magazines the war in Vietnam has a latent significance very different from its manifest content. Far from repelling us, it appeals to us by virtue of its complex of polyperverse acts." - Ballard.

May 10, 2004

Goldfrapp - Strict Machine. Does everything B*****e wants to do, but fails to, on 'Naughty Girl'. An update rather than a wearily sexless recapitulation of Donna Summer's aching, effortless cyberoticism.

May 08, 2004

I agree with what eppy says here about Eamon - great single, f'sure - but as per my Abba post, I disagree that pop is essentially adolescent. Off the top of my head, I can think of four counter-examples that disprove this claim: Abba, of course, Roxy, Kate Bush and Fleetwood Mac. Pretty powerful counter-examples.

EVERYBODY'S GOTTA LEARN SOMETIME

If we had the chance to do it all again

Tell me, would we?

Could we?

It might be that Charlie Kaufman and Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is the most Philip K Dick-esque film ever.

Oddly, it achieves this by freeing SF from the template that Ridley Scott established over two decades ago in Blade Runner, his adaptation of Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? For all its merits, Blade Runner was not especially Dickian. The heroic register, the expressionist grandeur, have in fact more to do with Scott than PKD. Reading A Scanner Darkly or The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldridge, what is most striking about them is their shabbiness, seediness and scuzz, both moral and physical. Dick rubbed SF’s upturned nose in the quotidian mess of failed relationships, drug dependency and cheap media.

Kaufman is the master of scuzz (just remember what his script for Being John Malkovich had Cameron Diaz look like); or it not quite scuzz so much as an unvarnished, unscrubbed real. We’re so habituated to cinema’s default glamour that it’s shocking to see the opening close-ups of Jim Carrey, all rumples and wrinkles, non-designer stubble, disordered hair. Kaufman’s dialogue, with its longeurs, and its awkward, unwitting revelations is the spoken equivalent of this visual sobriety. Despite what you may have heard, Eternal Sunshine is, in every good way, muted: there’s none of the sleek black gloss of The Matrix trilogy. It refuses to Turn the Contrast Up in the way that is de rigeur in contemporary media.

Eternal Sunshine takes up the legacy which Dick bequeathed to SF: the reductive materialist thought that memory and personality are as physical – and therefore as replicable – as a digital file. Its premise is simple: what if you could have your memories of someone technologically removed? (In one of the many wickedly humorous moments, Carrey’s Joel asks the Doctor, ‘is there any danger of brain damage?’ to which the doctor replies, ‘Well, strictly speaking, the procedure is a form of brain damage.’)

Actually, a closer parallel than Dick might be the forgotten queen of cyberpunk, Pat Cadigan, whose Mindplayers and Fools staked out the territory that Eternal Sunshine explores: memory as a treacherous landscape through which characters can move, identity as an editable program.

Director Michel Gondry brings a visual inventiveness to his realization of Kauffman’s vision that is never obtrusive or indulgent: backgrounds fade into white-out, space curves in Escheresque loops, houses disintegate in nightmare collapse. For once in contemporary SF, the FX are led by concepts rather than the reverse.

But Eternal Sunshine, naturally, must be positioned not only in relation to SF, but also in relation to romantic comedy. It’s like a romantic comedy written by Beckett – a romantic tragicomedy - in which romance dies not in some passionate combustion, but fizzles out into uncomfortable, aseptic banality. One of the most painful scenes in the movie has Carrey and Winslet sitting amongst the ‘dining dead’ at a Chinese restaurant. ‘How’s the chicken?’ ‘Good.’ (From now on, we can refer to the time when you know that a relationship has died as 'the Chicken Moment.')

If Beckett is a reference point, it’s the Beckett Nina has evoked: not the miserabilist Beckett of cliché, but the Beckett of the evanescenent epiphany . The lines Nina quotes from Krapp’s Last Tape perfectly capture the tone of the memories. 'I lay down across her with my face in her breasts and my hand on her. We lay there without moving. But under us all moved, and moved us, gently, up and down, and from side to side...' Here is Krapp listening to his tapes for the last time; here is Joel through his memories even as they are deleted. Joel and Clementine lying on the frozen lake, the distant traffic lights bobbing like will o’ the wisps, him knowing, even then, that this is a moment of unparalleled joy.

An early scene set within Joel’s memoryscape sees him running down a street after Clementine: space curves and bends back on itself, and Joel finds himself moving away from and towards the same point simultaneously. What was once behind him is now in front of him, and vice versa. Another striking scene – reminiscent of Potter’s Blue Remembered Hills - finds Joel fleeing through his memories with the remembered Clementine, fetching up in the chintzy seventies kitchen of his childhood, Carrey crawling and bawling under the table dressed in toddler’s clothes. In Kauffman’s hands, Freud’s bleak message – that we are condemned to repeat the past forever, that the child is father to the man, that life itself is nothing but a repetition – is given a positive, fatalistic twist. When their act of memory erasure is exposed to Clementine and Joel, they have the opportunity to choose to live through their relationship again. It’s always painful for a lover to overhear their partner detail their faults, but for Clementine and Joel – who, so far as they have concerned, have just met - to hear a tape in which they rip each other to shreds is almost unbearably traumatic. But opting, in spite of this, to live through the relationship again - even knowing how it ends: well, it's a gesture far more romantic than anything Winslet did in Titanic. It's easier to love a dead partner - one who has been sublimated into pure memory - than one who leaves hair on the soap.

So Clem and Joel opt not to change the past, but to affirm it, to live it again. Thus the couple manage to meet the challenge that Nietzsche’s little demon poses. “What, if some day or night, a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: ‘This life, as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh… must return to you—all in the same succession and sequence—even this spider and this moonlight between the trees and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned over again and again—and you with it speck of dust!’ Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: ‘You are a god, and never have I heard anything more divine!’"

Every story ends unhappily if you follow it long enough. Life is not about endings, but middles (and muddles), the in-between.

Maybe we should try

The same old scene...

To see Kauffman's original script, go here.

May 07, 2004

IT'S 3:30 A.M.. LET US SAY ONE IS 'COPYING FROM A BOOK'

Speaking of Ccru....

Undercurrent brings news of a stupefying example of 'plagiarism'. It actually goes far beyond plagiarism, since the culprit's typical MO involves reproducing the original texts with the odd word replaced, sometimes with comic effect. e.g. 'Coarse materialism' becomes 'course materialism.'

I don't think I've ever encountered quite so sustained an example of textual theft. What I love is that he has the gall to put 'copyright Adrian Gargett' on some of these witless collages.

Quite what the motive is for Gargett replacing words in the original texts is especially mysterious; it's not as if this will disguise the text to the reader who's familiar with it; but it effectively robs him of any argument that he is merely propagating the texts (in a way that bears out their machinic impersonality).

Some argue that Gargett is engaging in a Sokalesque spoof on the academy in which he exposes for ridicule the ludicrous laxness of peer review. Perhaps....

The whole thing is both utterly hilarious and terribly sad...

NEW BURROUGHS BOOK

This new collection of Burroughs essays is out on Pluto Press; it includes a contribution from Ccru.

Here's the press release:

RETAKING THE UNIVERSE: William S. Burroughs in the Age of Globalization

Edited by Davis Schneiderman and Philip Walsh

Published by Pluto Press

May 2004 / 328pp / Pb £17.99 / $24.95 / 0745320813

“An artist with his antennae up, Burroughs responded to the same cultural landscape that spurred and shaped so much of contemporary theory: the manipulation of images by mass media, space travel, Cold War politics, genetic engineering, sophisticated surveillance systems, chemical/biological warfare, nuclear arms proliferation, genocide, environmental disaster, global inequalities in the aftermath of colonialism, a surge of religious fundamentalism, electronic communications, more open expressions of various forms of sexual desire, and so on.” [extracted from chapter 1]

With a proud history of publishing the very best in progressive, critical thinking across politics, the social sciences and literary theory, Pluto Press is proud to present this title on our list.

'Schneiderman's and Walsh's new collection should mark the beginning of a new and wider view of the contemporary implications of Burroughs's thought. This book is retaking the universe of Burroughsian interpretation – starting now.' James Grauerholz

This anthology of writings on the work of William S Burroughs offers genuinely new and contemporary scholarship on a hugely influential and still widely read and studied cultural phenomenon. The move beyond the merely literary, to argue for the social and political dimensions and relevance of Burroughs’ work, is what makes this particular collection a distinctive one.

If you would like to feature an extract, request a review copy, or feature this title to your members at a substantial discount, please e-mail webmarketing@plutobooks.com.

May 05, 2004

REPHLEX VS WILEY

Jess with a real great post on the Rephlex Grime LP. Glad he liked it too. Must say that I've played the elpee pretty compulsively since I received it a week or so ago, and it just gets better with every listen.

Stick with Slaughter Mob, though, Jess. I, too, was most taken with the MarkOne and the Plasticman tunes initially (especially the awesome MarkOne opener, 'Stargate 92'). But the Slaughter Mob tracks are real growers. To whet Nick Gutterbreakz' appetite even further, their 'Fireweaver' is almost like a 00's Cabaret Voltaire, with its paranoia-as-a-form of resistance worldview ('Fear is the most powerful weapon we have' 'Trust no-one', 'Question Authority') and simmering electro insinuations. Ditto the bleak acid of 'Black Hole': all Voice of America-style pitched-down vocal samples and viscous synths.

By contrast.....

I have to assume from the near-radio silence on the Wiley LP hereabouts (ironic that there's so little on the blogs about it, given the Petridis review) that everyone is as underwhelmed by it as I am. It's not that it's bad. It's more that it only just meets expectations and in doing so falls short of them. I haven't yet experienced anything like the compulsion to play it that the Rephlex LP excites.

Wiley palls by comparison not only with the most obvious parallel, his protege, Dizzee, but also by comparison with himself. If - as Simon sagely insisted - Dizzee 'superls' as both a producer AND an MC, the discrepancy between Wiley's abilities on the mic and on the PC are all-too evident on Treddin on Thin Ice. Again, it's not that Wiley is a bad MC. Far from it. But he's not good enough to stop you hungering for the desolated splendour of the eskidubs. As an MC, Wiley lacks Dizzee's rhythmic invention, verbal exuberance, affective register and - to put it at its simplest - his 'vocal grain', that ineffable but completely material vocal signature. As Nick Gutterbreakz, one of the few to break cover on this subject, has plaintively said, the painfully attenuated 'interlude' versions of 'Ice Rink' and 'Eskimo' cry out to be heard in their entirety. (Nick's right that 'Special Girl' is like some E. London cousin of a Kanye West track; but where Kanye has a mellifluous spirituality [the speeded-up vox playing like cyborg angels], the helium samples on the Wiley track sound like crystal meth demons haunting some piss-stenching Bow underpass.)

There's a strange paradox about the LP, in that Wiley's repeated insistences that 'his heart is cold' actually add a human warmth to the tracks that they gloriously lack in their vocal-free versions. Any vocal would be an unwelcome interloper in the eerie calm and smoking rubble of 'Ground Zero''s depopulated carnage. I know I won't be alone in seconding Nick's call for an LP of eski instrumentals.

May 04, 2004

CHRIS MORRIS IS ALIVE AND WELL....

Just heard on ABC news: 'He said he was forced to appear as part of a human pyramid....'

PAGING ALEXIS PETRIDIS

Popjustice refers to records as TEXTS! (See Tuesday singles sweep). Well, someone had to do it. Eventually.

May 03, 2004

THIS IS (NOT) THE GIRL

David Lynch versus Dennis Potter....

The affinities between the work of David Lynch and Dennis Potter have often been remarked upon. No doubt they would have been confirmed if Lynch and Potter’s long-planned collaboration on an adaptation of D. M. Thomas’s The White Hotel had come to fruition.

Superficially, the works of Potter and Lynch which have most in common with each other are Twin Peaks and The Singing Detective; both are explorations of the detective genre by televisual auteurs; both display their authors’ signature obsessions with popular culture; both examine the interplay between sexuality, memory and identity – but the most Potteresque of Lynch’s films is actually his masterpiece and most recent feature, Mulholland Dr. In cross-fertilizing the soap, detective and Horror genres (amongst others), Twin Peaks contaminated realism with strains of the marvellous. Yet its concerns were epistemological (‘Is this real or not?’) rather than ontological (‘What is reality?’ ‘What is the reality of this?’) Mulholland Dr, meanwhile, like The Singing Detective, is reflexively engaged with its own fictionality.

The ‘standard’ interpretation of Mulholland Dr claims that its first two-thirds are the fantasy/ dream of failed two-bit actress Diane Selwyn, whose actual life is allegedly depicted, in all its quotidian squalor, in the final section of the film. This would underscore MD’s striking similarities to The Singing Detective, whose complexly-interacting narrative lines are weaved from the fantasies and memories of the convalescent pulp author, Philip E Marlow (Michael Gambon). Yet such a reading is ultimately unsatisfactory. As Timothy Takemoto argues, (you have to scroll down to his piece, ‘Double Dreams in Hollywood’) to see the second part of Mulholland Dr as real is inherently conservative in its assumption that there is an unambiguous reality to which we can ‘return’.

Following Zizek, Takemoto suggests that what MD presents is not an exposed ‘reality’ but a ‘grey fog’ of competing, incommensurable realities, from which desire and will are never extricable. (An homologous case is Kubrick’s near-contemporaneous Eyes Wide Shut, which is standardly interpreted as entirely the dream of the protagonist, Tom Cruise’s Bill. What this reading of Eyes Wide Shut has in common with the dominant readings of Mulholland Dr is a confidence in the possibility of parsing reality from desire, a distinction which both films disturb, as the very title of Kubrick’s film indicates).

Lyotard famously defines postmodernity as an ‘incredulity towards meta-narratives’ If the standard interpretation of MD were valid, then, far from being incredulous towards meta-narratives, it would be presenting a meta-narrative (an empirical realism focalized through a psychological interiority).

In his earlier Libidinal Economy, Lyotard opposes ‘the representational cube’ to the Moebian strip: a single-sided figure, with no inside or outside.

In tracing the endless surface of this moebian strip, both Lynch and Potter exemplify a libidinal postmodernism diametrically opposed to self-conscious, auto-referencing ‘PoMo’. Whereas PoMo mourns the absence of a stable transcendent plane, a meta-space ‘above’ the fiction, typically identified with a self-present, self-conscious subject (God/ the author…), Lynch and Potter’s fiction explores the Escheresque flatness of a plane of immanence. Far from being metafictions, then, Potter’s and Lynch deny the possibility of any meta level.

The Real of Mulholland Dr is not Diane’s supposedly waking world, but the paradoxically entrancing insomniac realm of Club Silencio (which, in acting as the gateway from the first section of the film to the second is like the ‘cut’ of the moebian band that when sutured together, transforms the two sides of the piece of paper into a single strip). I say ‘paradoxically entrancing’ because the scene is ostensibly demystifying. Yet only ostensibly so; like Magritte’s ‘This Is Not a Pipe’, Club Silencio, reminiscent of the Black/White Lodge in the first and final episodes of Twin Peaks and as intensely charged as anything in Lynch’s oeuvre, demonstrates film – and art’s - irreducible sorcery. Club Silencio’s scenario is thoroughly Potteresque. The entertainment is provided by perfomers who mime onstage to a pre-recorded soundtrack, much in the way that Potter had the characters in The Singing Detective and Pennies From Heaven lip sync to thirties’ pop. Despite the complete ingenuousness of the magician-compere’s words – ‘There is no band. What you will hear are recordings.’- we (the audience) are nevertheless unable to resist the seduction of the spectacle. So when the apparent singer, Rebeka Del Rio, collapses but the music continues, we are shocked. Something in us compels us to treat the performance as if real.

It would be difficult to conceive of a more compelling parable for postmodernism. Just as Postmodernism simultaneously exposes and disturbs generic conventions whilst also participating in their ‘lure’, so the Silencio audience is made aware of the artificiality of what they are experiencing at the very moment that they succumb to it. (See here for an analysis of this in relation to Twin Peaks and The Singing Detective

There is of course nothing less mendacious, less dissimmulatory, in cinema’s history of illusion than the scene in Club Silencio. What we are seeing and hearing – the film itself - is a recording and nothing but. On the most banal level, this is the Real which the ‘magic of cinema’ must conceal. Yet the scene haunts for reasons other than this. It challenges the audience (us!) to recognize that our own lives, the roles we perform when we leave the auditorium, are themselves recordings, scripted by forces outside the self whose ‘substance’ turns out to be itself nothing more than a palimpsest of influences.

Lip syncing is a model for a subjectivity that is essentially empty; that is driven, not driving; that is a rendition, not an origination; whose inside, like that of the moebius band, is all outside. Watching Club Silencio I’m reminded of Philip K Dick’s gnomic but suggestive remark that ‘life is not lived, but lived through.’

(It’s worth noting parenthetically here that both Potter and Lynch are most at home with pre-rock pop. Potter famously fills his soundtracks with the wistful tearoom pop of his childhood, while Lynch favours Badalmenti’s oneiric jazz or Julee Cruise’s ethereal doo-wop. Even when the music is chronologically of the rock era, it is temperamentally pre-rock – Lynch’s favourite, Roy Orbison, for instance, although supposedly a rocker, was always a crooner at heart. Not coincidentally, Lynch and Potter are at their least convincing when trying to deal with rock – Potter’s dawn-of-rock opera Lipstick On Your Collar and Lynch’s rebel rocker fantasy Wild At Heart are amongst their weakest work.)

Mulholland Dr shares much with the television serial Potter wrote after The Singing Detective, the troubled Blackeyes. Blackeyes, whose protagonist, Gina Bellman, physically resembles MD’s Laura Elena Harring, was intended to be Potter’s examination of the production and manipulation of female subjectivity (and his own desiring-complicity with this manipulation). The Lynch female – like the Potter female (and the Ferry female, come to think of it) – is a largely fantasmatic concoction of blood-red lipstick, nail polish, high heels and long hair. Tellingly, the iconic image of both Lynch’s Twin Peaks and of Potter’s The Singing Detective is a dead woman (Laura Palmer wrapped in plastic; Sonia/ Philip’s mother dredged up from the Thames under Hammersmith bridge), just as Mulholland Dr revolves around a female corpse.

But in situating women as both dreamers and the dreamed, MD's examination of the desiring-trajectories of Hollywood’s factory of dreams, succeeded in a way that Blackeyes never did.

May 02, 2004

ONE FOR ADRIAN MADDOX...

A wonderful contribution to the Britannia Moribundia canon by old-hand and k-punk fave Michael Moorcock in last week's Guardian:

'Cheap renderings and patched stucco are moulded by a natural graffiti spelling out the dreams of failed novelists who come to escape, to set down their stories, before it dawns on their horrified minds that the bungalows and boarding houses are as hungry as the sea. Stay too long and you inevitably drown in a quicksand of disappointment, seedy nostalgia and self-deception. Here, on the shingle of Kent and Sussex, East-Enders habitually come to die, just as south and west Londoners choose Worthing or Bournemouth as their final resting places, no longer able to attain the dormitory heavens of Brighton and Hove.

Sidling around the Estuary, Sinclair, via Norton, has learned the secret of the English seaside: it was designed only to be visited. This is where desperate immigrants, former showbiz stars and ancient juvenile delinquents seek asylum. To live here for more than a few weeks is to be caught in a 1950s time-trap where all the prejudices, loyalties, hatreds, myths and desires of immediate post-second world war England constantly recycle themselves.'

(Thanks to Sphaleotas for drawing my attention to this nugget.)