June 28, 2007

June 23, 2007

June 21, 2007

June 20, 2007

Calling South London massive

I'm teaching a five-day Critical Thinking course at Orpington next week. If anyone has the time available and wants to acquire some Cold Rationalist intellectual weaponry, then please come along. Email me at k_punk99[at]hotmail.com for details. It's free, and you can see me in action, if that's of interest. If you want a recommendation on my teaching, a student said yesterday, 'Mark, you shouldn't give up teaching, because if you do lots of people will miss out.' Which was one of the nicest things that has ever been said to me.

Tent state university

'Tent State University UK (or Tent State) is an initiative of an autonomous group of staff and students at the University of Sussex, inspired by the national Tent State University movement in the United States.'

TENT STATE TIMETABLE:

WEDNESDAY June 20th

10.00 World Social Forum Presentation and feedback

11.00 Vietnam Protest Art and Talk

12noon Who Really Ended Slavery?

13.00 Lunch and EDO Brighton’s Bomb Factory

14.00 Reducing HIV/ AIDS Stigma and Discrimination

15:00 Students Against Trident and Nuclear Proliferation

16.00 Africa Fighting Back

17.00 Dinner

18.00 Films and Music

Thursday June 21st

10.00 Patriarchy in Everyday Life

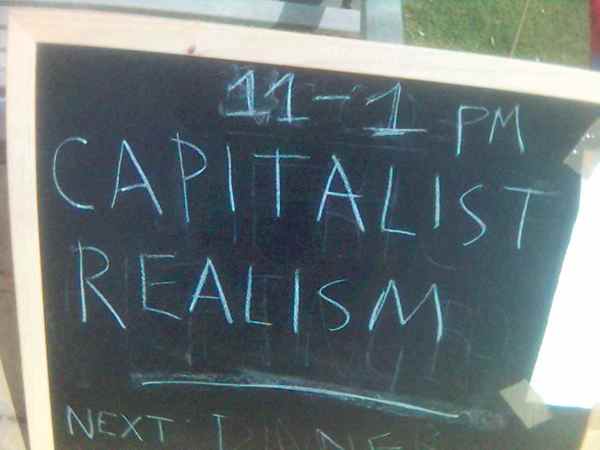

11.00 Capitalism and Realism

12.00 Capitalism and Realism

13.00 Lunch and Free Palestine

14.00 Women and Global Violence

15.00 Attacks on Civil Liberties: Brighton NO2ID

16.00 Can Patriarchy Have a negative Impact on men?

17.00 Dinner

18.00 Films, Music and Silent Disco!

Friday June 22nd

10.00 Securing Human Rights, Peace and Sustainable Development in Africa: The Case of Zimbabwe

11.00 Gender Fucking or Fucking Gender: The Poster People for Post-Modernity

12.00Lunch and An Introduction to Anarchism

13.00The Need for Global Militant Environmentalism: Eco-Uni, plane Stupid and Permaculture

14.00 Pan-Afrikanist Futures

15.00 Pan Afrikanist Futures

16.00 Fighting Racism in Our Communities

17.00 Dinner and Final Plenary!

18.00 Films and Music

Lousy celebrity makes record

(OK, contary to what I suggested in the previous post, I have managed to find a little time for a quick few words today).

Tim makes some excellent points about the 'foreshortened critiques of capitalism' involved in some of the response to Paris Hilton's incarceration.

Campaigning to keep Hilton in jail has no more political significance than campaigning to free her - but then the 'Free Paris' demands (as described by a bemused Simon here) are not political, except symptomatically. They are statements of flaccid flaneurism (a flaneurism reduced to the most dryly theoretical of poses), a flaunted but uninteresting decadence, whose disavowed libidinal charge comes almost entirely from baiting the haters - what I have previously called a resentment of resentment. Would that Paris' defenders were voguers, who had an intense interest in their appearance, clothes and mannerisms, who wanted to make of themselves a work of art. The shameful, embarrassing, and silly 'Free Paris' acting out - I refuse to dignify it with the term 'campaign' - is vogueing without the drive to self-beautification, a spectatorial pretence of worship. For, naturally, the worship is all a matter of being seen to worship her - what else could it be? And who is supposed to be watching?

I don't hate Paris Hilton. I hate Katie Hopkins, because I've confronted people like her, they have some reality in my life. (The only hyper-rich heiress I've dealt with is Her Majesty Le Chabert, and, certainly, I find her moralising self-hating sanctimony far more loathsome than Hilton's blank pleasure-seeking.)

The truth is that Hilton is an object I am unable to cathect in any way whatsoever - in other words, she is boring. She is a symptom - of her class and background - but an uninteresting one. In fact, her utter lack of remarkable features, the so-formulaic-a-computer-program-could-have-predicted-it pattern of her dreary rich girl life, may be the only interesting thing about her - but you would have to the austere asceticism of a Warhol to maintain that position.

More than the dull reality of Hilton herself, it is the pro-Hilton posturing that is a serious symptom - of a suiciding of intelligence, of cultural bankruptcy and exhaustion. It is the logic of cultural depression, of gradually but implacably lowered expectations, that has produced the over-investment in Hilton; a logic of devaluation, not revaluation - a logic of betrayal, of a failure of fidelity to pop culture's great events. Imagine all the proscriptions, the prohibitions, the self-denial involved in the pretence that anything at all is at stake in Hilton's record. Reflect on how a series of tortuous theoretical convolutions have led to a position that is, in both political and aesthetic terms, about as elitist as one could imagine - elitist precisely in the sense that it consists in a demonstrating of one's superiority to the plebeian masses (who did not buy the record - why not? Were they deluded? Duped? Didn't they know about it?) Let's be clear, though, those who so ostentatiously parade their love for Hilton - and it is all about the parading - have outed themselves: theirs is not a serious critical position, but a gentlemen's club weekend activity for stressed executives. They don't live and breathe pop culture, as I hope the readers of this site do; in fact, the category 'culture' - like 'history' or 'politics' - doesn't exist for them. It is all just entertainment, leisure and consumer preference, in other words capitalist realism, interpassive nihilism. This is what this discourse must be treated as: a noxious ideological fog, an apologia for mediocrity, a defence of boredom and the boring. Which is exactly what capitalism wants. Don't make any demands. Don't be critical. Make the best of what's there.

The arguments against Hilton-as-object are ultimately aesthetic ones. The merely mediocre record has more going for it than the substandard Paris-the-celebrity. The problem is Hilton isn't aristocratic enough; isn't sufficiently artificial or invested in artificiality; isn't a weaver of opulent fantasies. Compare Hilton to the artistry of the working class-born Kate Moss - Moss, whose life may well be as boringly hedonistic as Hilton's, but who as an artist (and it is only misogynistic prejudice that maintains that modelling cannot be artistry) cultivates an opacity-without-depth, the fascinating distance of the object that gazes. Working class fantasies about the wealthy are far more interesting than the reality (as Bryan Ferry long ago found out, to his cost.) And if there is a leftist moral to be drawn from the Hilton phenonemon it is this: that the lives of rich people are not interesting.

June 18, 2007

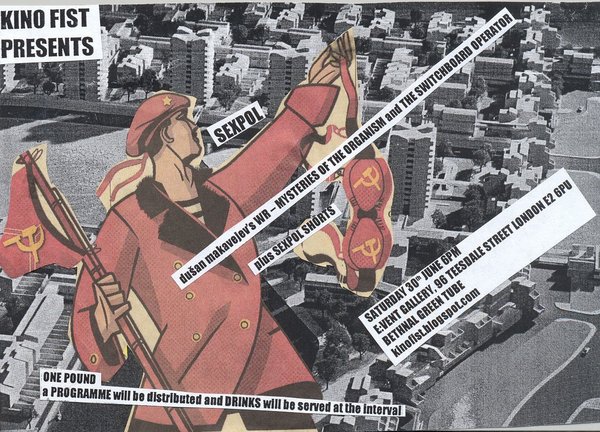

I'm going to be away for a few days - one of the things I'm doing is speaking on Capitalist Realism and education at the Tent State University event in Brighton on Thursday morning. I have two post-Edelman Queer posts in preparation - don't let me slack on those, they're important. With any luck, there should be at least one post up by the weekend; in the meantime, check out the superb contributions to the Edelman discussion made by Owen , Dominic and Daniel (there's a very interesting comments thread attached to Daniel's post, too).

Oh, and there's an interesting review of Faster than Sound in the FT, including a little interview with Philip Jeck.

Reaction shots

|  |

Last week, Lawrence Miles wrote of Steven Moffat's overrated Dr Who episode from the last series, 'The Girl in the Fireplace' that it 'as if the author's so desperate to write about the tragic consequences of the love affair that he hasn't bothered figuring out how the characters might actually fall in love to begin with.' Miles, as so often, has identified one of the defining pathologies afflicting postmodern entertainment in Britain: premature emotional ejaculation.

Case in point: the ghastly, grand guignol grotesquerie of Britain's Got Talent, a programme that tells you far more about the current state of British popular culture than the tired Big Brother (is anyone watching this year?) What is interesting about Britain's Got Talent is the way in which it distils current TV conventions to the point of being indistinguishable from an Armando Ianucci parody. The acts vary in quality from the watchably appalling (a midget-in-a-handbag routine, for instance was almost Lynchian) to the unwatchably mediocre - but, no matter, because the show is not about them, it is about the 'emotional journey', which we are led through in three stages that years of X-Factor and Pop Idol have second naturalized. First, we have the back story - in which, with no crass emotional trigger left unhammered - we are fed the tragic conditions that are being overcome, the illnesses fought against, the griefs bravely faced; then, there's the performance itself, often so boring and inconsequent that Ant and Dec have to be shown at the side of the stage cavorting and mugging in order to maintain flagging interest; and thirdly - the real point of it all - the emotional ejaculation, the looks of triumph and disaster over which the camera pores in cloying slo-mo, while 'I can be your hero baby' or 'here, there, there's nothing to fear' or some other hyper-hackneyed sentimentalist anthem belts out. In the past, I've been tempted to call this 'emotional pornography' but, by comparison with the obscene speed of TV's tear jerk-offs, porn-time is almost quaint in its patient distention. In porn, it takes twenty odd minutes before you get the money shot; but the kistch sturm-und-drang reaction shot arrives in under three. It's pretty clear that the competition is not about the acts at all, but which back story is most mawkishly exploitable. A lisping six year old - who reminds me of the child talent competition in the last series of League of Gentleman ('Cherry Bakewell is chair of the judges? Good, good') - was the tabloid favourite.

Even quizzes are now required to adhere to this tripartate structure. As, naturally, is Drama. Which brings us back to Dr Who. Saturday's episode was an ultra high speed tour through the conventions of current TV: it was so fast-paced it felt like a simulation of a series of neurological spasms. At the same time, it felt bizarrely contentless - you are being hectored through at such a rate, that you do not feel that you are actually watching the programme itself. Jameson has said that the trailer is the form most with late capitalism, and, like much TV now, Dr Who feels like a trailer for itself, an impression reinforced by Murray Gold's awful bombastic orchestral score. Gold's music - produced to the order of Russell T Davies, who insisted that the show needed a 'Hollywood' score - is both formally and texturally inapt (it could be shipped in from any action film whatsoever) and emotionally redundant, (screaming at us what to feel, in case the emotional manipulations of the script aren't bludgeoning enough). Neurotic hucksterism (cynicism) and sentimentalism (piety) become indistinguishable, just as they are in advertising, whose logic and form, as Baudrillard long ago predicted, has infected all TV now. Every time David Tennant goes into his nauseating paean to 'indominatable 'uuuumans, gor blimey, ain't they marvellous, surviving 'ere at the end of the yewwwniverse, god bless 'em', I think of commercials for BUPA.

The twitchy urge to keep selling us what we are about to see, the fear of slowing down for one minute, the designing of every feature of programming to fit some focus-grouped demographic specification, is a consequence of what Owen has called the BBC's failure to be the BBC. Since there is no 'public' to service any longer, the BBC justifies itself by its pursuit of market share. Defenders of capitalism will argue that it delivers diversity, yet a quick survey of the relentless monotony of TV quickly gives the lie to that illusion. Hedonic conservatism goes hand in hand with retrospective impossibilization. It has now become impossible to imagine something that was, in fact, once the case: a teatime television show that used experimental electronic music. This , we are told, cannot happen any more - but is there more to this than the self-fulfilling prophecy of TV execs, or is it, terrifyingly, indicative of a terminal, irreversible condition?

Last night, as with Human Nature/ Family of Blood two weeks ago, there were flashes of the old Who. I must confess to have had gooseflesh and a tear in my eye when Derek Jacobi proclaimed, 'I...am.... the Master...' It was as if Russell Davies, who has been maliciously melting our childhood toys down into PoMo gloop on the pyre of capitalist realism, miraculously relented and gave us one back. But, quick as a CGI flash, it was snatched away again, as Jacobi was regenerated into the capering and japing John Simm (the most overrated actor on British TV), and normal service was resumed.

It's unfair to judge Simm on the basis of the three or so - albeit dreadful - minutes he had in the role last night. Perhaps he'll seem less like the Riddler in the next two episodes. But even if he doesn't turn out to be Tennant-but-EVIL (and my bet is that the Master will have boned up on his 21C popcult references by the time we see him in the next installment, ready to trade Harry Potter references with his adversary), my problem with Simm is much like my problem with Tennant. It's physical. Simm is too baby-faced toothsome to play The Master. Like Tennant, he doesn't look weird enough. Watching Tennant and Simm, I am constantly made aware that these aren't Doctor Who and the Master, they are actors playing Doctor Who and the Master. With the classic Doctors, from Hartnell to Tom Baker, the face and hair were three quarters of the character. Hartnell, Troughton, Pertwee and Baker were character actors, not leading men, and they had faces - interesting faces - to match. But in today's TV, with its age and looks apartheid, there is little place for anyone whose face is unusual, or over fifty.

It's not as if the Master in the original series was anything other than a standard melodrama turn. But something about the physical presence of Roger Delgado gave the cartoon menace an edge. With Simm, it looks like we're going to get the usual postmodern wisecracking mad-as-a-box-of-frogs hyperactive model of evil. The problem is that this is not a convincing - or interesting - picture of either madness or evil. (When did this tedious version of madness and evil begin? I'm afraid that the 'Here's Johnny' moment in The Shining was probably pivotal; and another moment of Nicholson self-regarding contempt for the audience, his Joker in Burton's dreadful Batman, pretty much established all of the conventions of PoMo mad evil. Hopkins' hamtomime Lecter is another key moment in this genealogy, of course.)

One effect of capitalist realism is de-mythologization: it seems that the failure to envisage alternative political or social systems has also corroded the ability to imagine monstrosities. The poverty of teratological innovation has been evident in film and TV SF for the last twenty five years (China might think about consulting his lawyers about the insect headed woman in this week’s Who, though). But psychological monstrosity has been equally badly elaborated. The BBC's Jekyll, whose first episode was broadcast last night, was another example of this imaginative failure. The hole at the centre of the programme was James Nesbitt's Hyde. Nesbitt used the same pleased-with-himself, I'm made, me style Simm had used earlier in the evening (I should point out here that Jekyll was scripted by Steven Moffat). But smugness is not menacing. It's just irritating.

* 'Vintage' Dr Who was mocked on arch-smugonaut Angus Deayton's dreadful new panel show last night. I switched over just after Deayton turned out a received idiocy about classic Who having the 'budget of a village pantomime but with worse production values'. Deayton is so ontologically smug that it's impossible to imagine that punchable smirk wiped off his face in any circumstances whatsoever. After tabloid revelationsa few years ago that would have caused anyone else to head for an arctic Fortress of Solitude, Deayton returned, smug as ever, as indefatigable as Michael Myers. Would anything stop him being smug? Pulling his fingernails out one by one, maybe... Well, we could have a go...

June 17, 2007

Correspondence(s)

Simon is right: the omission of Eno from the Suffolk hauntology post is really quite an oversight, especially odd since Eno, predictably, came up a number of times in conversations at the Bentwaters event last week. I suppose it does prove my point about the inexhaustible richness of Suffolk's cultural landscape; and there is something apt about leaving out Eno - who theorised and exemplified the role of artist as offstage-enabler - from a post on hauntology. Nevertheless, it was odd that I forgot him, especially as I had planned to speculate on the relationship between the title 'On Land' and Suffolk's crumbling coastline. Odder still, is that, until yesterday, I had not visited the 'little wood ... which stands between Woodbridge and Melton' that On Land's 'Unfamilar Wind (Leeks Hill)' invokes, even though the wood stands not half a mile from where I'm sitting now. Leeks Hill turns out to be rather larger than Eno's description had led me to expect - as I walked through the wood, I played the five minute track four times on my iPod, and didn't by any means walk all the way around it. Listening to 'Unfamiliar Wind (Leeks Hill)' in the space it was designed to evoke was every bit as uncanny as you'd expect; the wood was drying in the late afternoon sun after heavy showers earlier in the day, and it was difficult to definitively determine which of the wildlife calls and coos I was hearing belonged to the track and which to the damply bright woodland environment. (Interesting that Simon should mention 'false memory' and Boards of Canada, since Adam Parkinson, an MA student at Newcastle, recently sent me a very interesting essay on BoC and hauntology which refers to Freud's claim, in his essay on 'Screen Memory', that we may not have any memories from childhood at all.)

Context isn't everything. In response to the Woodbridge boats post, reader Andrew Parker writes:

- A sailor sees a boat.

A pyromaniac sees fuel.

A termite sees food.

Once the sailor values warmth more than sailing he sees fuel for a fire and the termite sees the error of his ways.

Context is everything.

But the fascination of Graham's philosophy of objects is that it based on a rejection of this move. Every interaction between objects presupposes a mutual 'caricaturing' - when fire burns cotton, or when a termite eats a rotting boat, each only 'perceive' certain features of the other, ignoring the rest, so that 'some sort of objectification occurs even at the level of sheer matter'. Graham's point, though, is that there is a subterranean remainder in every object that never enters into relations of any kind. 'If we could total up all the "contexts, roles and social goals" in which a specific bridge or flagpole [or decomposing boat] are currently embedded, this would not give us the being of these objects.'

The old hag. Reza writes:

- Another object helpful in exemplifying the enigma of decay (besides Woodbridge's boats) is the myth of the Old Hag in eastern and western Europe and Asia. Hag is a monster that does not die and does not begin to seem older while it maintains its monstrosity by indefinitely perpetuating its aging process and infinitely getting older. It could constitute a good example for Leibniz when he was explaining his infinitesimal calculus.

Suffolk, centre of pestilence. English Heretic writes:

- There are some articles on the english heretic web site on Orford Ness (visitors guides and a video banishing rite! at Orford Ness). There's also a piece on the very hauntological hallucination of Ronald Ashford at Shingle Street. There's also quite a bit on Rendlesham (particularly related to the occultist Kenneth Grant, who considers Suffolk a "centre of pestilence"!). Along with my friend Phil Legard we did some recording close to the suspected site of the landings, which surfaced on the English Heretic annual as a track called Open the Mithraic Stargate. Finally the first couple of releases focused on the filming of Witchfinder General.

At the moment I am working on a release called Visitors Guides, which has got a piece assembled from recordings on location at Orford Ness, last August, as well as a superimposition of Crowley's Amalantrah working over Butley (near Rendlesham)... re-imagined as Pantruel.

... one of the ideas behind the [EH] project was to create these Ballardian type "kits" only in concrete form... maybe a film or a mock guide or fabricated found recording etc. The Dr. Champagne, Robert Navane characters who feature in EH releases are homages to Dr. Nathan and Travis in Atrocity Exhibition. Robert Navane is kind of Champagne's unfortunate experimental guinea pig.

Weird etymology. 'Strangely enough the word weird has come into modern English entirely from its use in Macbeth.'

June 16, 2007

Suffolk hauntology (some provisional notes)

- Dunwich is not even the ghost of its dead self; almost all you can say is that consists of the mere letters of the old name. The coast, up and down, for miles has been, for more centuries that I presume to count, gnawed away by the sea. All the grossness of its positive life is now at the bottom of the German Ocean, which moves for ever, like a ruminating beast, an insatiable, indefatigable lip. Few things are so melancholy - and so redeemed from mere ugliness by sadness - as this long, artificial straightness that the monster has impartially maintained. If at low tide you walk on the shore, on the cliffs, of the little height, show you a defence picked bare as a bone; and you can say nothing kinder of the general humility and general sweetness of the land that this sawlike action gives it, for the fancy, an interest, a sort of mystery for there is now no more to show than the empty eye-holes of a skull; and half the effect of the whole thing, half the secret of the impression, and what I may really call, I think, the source of the distinction, is the very visibility of the mutilation. Such at any rate is the case for the mind that can properly brood. There is a presence in what is missing ...

Henry James made these remarks in 1897, in his 'Old Suffolk' (later anthologized as part of English Hours). The fate of Dunwich fascinated the Victorian mind. The town had come to public notice in the 1830s as one of the 'rotten boroughs' eliminated by the Reform Act of 1832 - until the Act was passed, Dunwich, which then had a population of less than forty, still had the right to elect two MPs. Its notoriety led to a reawakening of interest of the ‘visibly mutilated’ town, and poets and painters - most, no doubt, taking advantage of the East Suffolk Railway, opened in 1851, - rushed to Dunwich to indulge in melancholy disquisitions on the vanity of physical existence. After all, the disappeared port was practically a vanitas painting brought to life - or to unlife; for, if as James notes, all the town's 'positive life' had crumbled away, what is left at Dunwich must be either a negative life or a negation of life.

There is rather more in James' observations than the penny dreadful piety and mawkishness which Dunwich brought out in many of its Victorians observers. James understood that, for the mind capable of brooding - and he insists, later in the essay, 'that it to the brooding mind only, and from it, that I speak' - there is a jouissance to be derived from the melancholy contemplation of what has disappeared, and continues to disappear.

There were major landmarks yet to disintegrate when James visited in 1897. He would have still been able to see All Saints Church - shown above in a photograph from 1904 - but by 1920, it, too, would be 'at the bottom of the German Ocean'. Twenty years ago, 'the bones of those buried in All Saints' graveyard protruded gruesomely from the cliff, and a single gravestone, to John Brinkley Easey, stood in an inconceivably bleak loneliness at the cliff top.' Now even those traces are long gone. Slow change is a constant at Dunwich. When I visited last week it had changed even in the comparatively short time since I was last there. Paths that were once walkable are now fenced off as unsafe.

Walking around the remains of Dunwich - and Dunwich is nothing but remains - is not, then, only to contemplate a past disaster. Even without global warming to accelerate the process, visitors can be certain that the land on which they walk will soon be consumed by the sea. The destruction of the great port 'with a fleet of its own on the North Sea' was dramatic and sudden, but if the erosion which still gnaws away at the coast around Dunwich is more gradual, it is also implacable. Global warming means that oceanic catastrophism confronts us now neither as a possibility that can be quarantined off in Science Fiction, nor one that is unthinkably distant. It was fitting that James should have devoted most of his ‘Old Suffolk’ to writing about Dunwich. Disappeared Dunwich, its churches and cathedrals now lying on the ocean floor, anticipates the near future of the whole county.

Darrell's battery at Landguard Fort. Photograph by James Hume

Suffolk has always been fighting two wars - the war against the sea, which will be lost, the groynes and the granite on the beaches providing makeshift coastal defences that will only retard the process of erosion, not end it; and also the war against invading foreign armies. Virtual wars have long shaped the county: the overgrown pill boxes, tank traps and deserted Cold War bases which make so much of the county resemble Tarkovsky's Zone are relics of conflicts that never occurred. The Martello towers which stud the coast stand waiting for a Napoleonic invasion that would not arrive, their squat and bullish defiance sufficient in itself to dissuade the French forces from attacking.

Four centuries of military history are compacted into the architectural palimpsest of Landguard Fort at Felixstowe, the last fort in England to oppose a full-scale invasion when, in 1667, four hundred soldiers stationed there repelled Dutch forces two to three thousand in strength. The Fort was modified and altered over the course of the next two hundred years; its most notable twentieth century feature is a gun battery which looks out to sea like a pair of modernist Easter Island statues. The Fort, gloriously preserved in much the same state of dilapidation it was left in when the military finally abandoned it in the 1970s, would be the perfect site for a hauntology event. In the dank, labyrinthine corridors lit only by bare lightbulbs, you can practically hear the raucous ghosts of the generations of soldiers once barracked here. From outside, the building looks like the sort of place that UNIT might have kept the Master prisoner in Pertwee-era Doctor Who. (I swear that the first time I visited, the man selling tickets said, 'It's like Tardis in here, much bigger than it looks from the outside!')

Inside Landguard fort.... photograph by Bacteriagrl

A little up the coast from Landguard, you come to Bawdsey. It was here that radar was developed, a massively undersung moment both in the Second World War and in the (feminist) history of cyberspace. Bletchley Park's role in cracking the Enigma code has been endlessly celebrated, in films, documentaries and novels, while Bawdsey has remained obscure. Yet its role in winning the Battle of Britain was decisive: radar - operated in the main by women - enabled an outnumbered RAF to overcome the Luftwaffe. The transmitter block at Bawdsey, open to the public throughout the summer, is a short walk from Bawdsey Quay, whose lights M R James described seeing from across the Deben Estuary in 'O, Whistle and I'll Come to You, My Lad'.

People often ask why I chose to live in Suffolk. The short answer is that, after a few visits here last year - themselves partly prompted by a desire to revisit childhood haunts, the sites where we spent our most memorable holidays in the 1970s - it struck me that the fictional and cultural richness of the Suffolk landscape is so dense that one could not exhaust it in a lifetime. I have not even mentioned Patricia Highsmith, who lived for a time a few miles away from here, in the little village of Earl Soham, and who set her novel A Suspension of Mercy in Suffolk; or Orford Ness, a place of 'missiles and marshes and bombs and birds', a 'poignant symbol of 20th century warfare', the home of the mysterious 'Cobra Mist' project; nor have I mentioned Matthew Hopkins, the witchfinder General, whose horrific campaign centred on Suffolk - Michael Reeves' lurid film about Hopkins was filmed in nearby Orford; or the Sizewell B nuclear power station, whose bizarre white dome is enough to inspire thoughts of how British television SF could be revived (if only Dr Who could be set in a readymade location like this, as it used to be, instead of inside some flashy, flimsy CGI sim, as it tends to be now). Oddly, almost nothing of the Suffolk that fascinates me features in Sebald's Rings of Saturn, a book venerated by many people I admire, but which did very little for me; I dream of one day producing a pulp modernist riposte to Sebald's mittel-brow text.)

Then there is Rendlesham forest, site of one of the most famous UFO incidents in Britain in 1980. Bentwater airbase, one of several Suffolk airfields abandoned by the USAF in the early 90s, is on the edge of Rendlesham. it was here that, last weekend, the second Faster than Sound event took place. Suffused by the gradually dying June sunlight, the site was fabulously evocative - a Ballardian space in which wildlife scampers amid the decommissioned furniture of the Cold War: disused control towers, hangars, mysterious and ominous and concrete bunkers, delicious in their brutalist functionalism. These Suffolk airfields are haunted by the terrible spectres of missions that, thankfully, did not occur, terminal commands that were never issued.

Bentwater at sunset. Photograph by Jon Wozencroft

Faster than Sound is the ‘experimental’ offshoot of the Aldeburgh music festival. Thankfully, the sounds on display here were not all Experimental (TM), i.e. Experimental as a set of rigidly-policed traits, defined by aversions (to melody, rhythm, etc.), like a negative image of everything that is interesting in music. If the standard methods of producing sonic consistency are to be dispensed with, the challenge is to produce new modes of consistency, not to simply churn out inchoate crackle and clicks. (I'll return to this in a post on Oren Ambarchi, who precisely succeeds in generating new means of sonic consistency.)

The highlights of the festival, then:

Hildur Guðnadóttir: first to perform in the 'Multi-National Circle', an outdoor concrete circle adjacent to a runway, Hildur overcame the unceremonious conditions in which she was asked to play (she wasn't introduced, and the late afternoon sunlight threatened to dissipate any atmosphere) with a performance of sombre rapture, her cello multiple tracked (with live playing augmented by laptop loops) into a slow sonic ocean sound whose ebbs and flows were shifted expertly around the six speakers of the ultravivid PA by BJNilsen. Hildur achieved something akin to the dark tranquility about which Dominic writes so eloquently, the suspension of all urgencies in a viscously tactile sound that gives the illusion of being poised on the edge of stasis (perhaps it's no accident that Xasthur use cello).

Pierre Bastien - with its menagerie of mechanical machines beavering away to produce triggering samples, Bastien's enchanting Meccano-musique plastique, brilliantly described by Pete Smiley on the Fact website as 'rusted and tragic and astoundingly beautiful, like early Tom Waits mixed with ancient ragtime', is what you imagine Jan Svankmajer would make if he was a sound artist rather than a film-maker. It's music from an alternative nineteenth century, steampunk hip-hop.

Philip Jeck, photograph by Jon Wozencroft

Philip Jeck - a godfather of sonic hauntology, of whose work I was shamefully ignorant until last weekend. Using two turntables and a magic-box of effects which defamiliarise the vinyl source material to the point of near-abstraction, Philip reconceives DJing as the art of producing sonic phantasmagoria. The occasional recognizable fragment (the Byrds, Mantovani-like lite classical kitsch, sonic objet as made all the more alluring by their partial submersion) thrillingly bobs up out of the whooshing delirium-stream. As he performs, Philip leans over his machines with a look of tender melancholy (perfectly captured in Jon Wozencroft's picture, above), almost as if he is tending a dying puppy.

Colleen. Photograph by Jon Wozencroft

Colleen. Colleen struggles. Sadly, the PA isn't turned up loud enough to compete with drunken boors, chatting bores and banging tunes coming from elsewhere on the site. She plays tracks from her new record, memorably described by Clare O'Brien as resembling either 'music played by aliens for a courtly masque staged on another planet or a talented child let loose into a music shop.' Colleen's delicate lite-baroque sound, produced by viola da gamba, acoustic guitar, clarinet, wind chimes and music boxes, and given an uncanny edge by unlive loops, is oversweet, excessively pretty, yet winningly so. 'Like a female Durutti Column', says Jon Wozencroft.

By now the Suffolk night has descended, and, as we leave, the poorly lit airfield is doubly eerie. Individual performances made Faster than Sound 2007 memorable, but the overall effect was too disparate, and I am left musing about the possibility of an unlive hauntology event that could make much better use of the semi-deserted spaces of Suffolk, an event that would be like some combination of film set, fiction and installation, in which each element forms part of kit, assembled differently by each person who attends. Is such a thing inconceivable?

June 11, 2007

When does a boat cease to be a boat? Prolegomena to a future photo-post

Rotting boats in Woodbridge, yesterday. Photograph by Jon Wozencroft.

- The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their place, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same.

The conundrum Plutarch described was already an old one when he wrote it down, and it has continued to haunt philosophy to this day. Can a ship be said to be the same ship if it has been completely rebuilt, so that not one of its original planks remain; and if it can be said to be the same, what is it that guarantees its identity?

In the twentieth century, Otto Neurath used the image of the ship rebuilt at sea for a quite different purpose. 'We are like sailors who must rebuild the ship on the open sea, never able to dismantle it in dry-dock and to reconstruct it there out of the best materials,' he wrote. Neurath's intention with the metaphor, which became one of the most well-travelled images in twentieth century philosophy, was to debunk any straightforward appeal to experience - philosophers must work in an already-existing context (of language and concepts), which they cannot simply step outside. (No doubt Neurath was thinking of Kant's 'broad and stormy ocean, the true seat of illusion, where many a fog bank and rapidly melting iceberg pretend to be new lands and, ceaselessly deceiving with empty hopes the voyager looking around for new discoveries, entwine him in adventures from which he can never escape and yet also never bring to an end.') Neurath's coherentism is, I think, one version of the now widely disseminated mode of philosophy Graham Harman, after Hubert Dreyfus calls 'deflationary realism'. ('According to deflationary realism, the inseparability of reality and context means that there is no way of talking about things in themselves apart from human practices.' Tool-Being, 122) In absolutely rejecting the 'quarantining [of] the cosmos within a network of human significance', in its pursuit of the 'subterranean power of things', in its positing of objects as endlessly opaque mysteries, Graham's philosophy returns us to the ancient questions posed by the riddle of Theseus' ship. What is an object, if its identity cannot be defined either by reference to its physical properties, or to any properties whatsoever?

The same question is posed in the work of Reza Negarestani but differently. The enigma Reza's philosophy confronts, one familiar to Medieval Scholastic philosophy, is: how far can an object rot before it ceases to be the same object? When does a change in condition become a change in kind? The small town in which I live, Woodbridge in Suffolk, was founded on the craft of boat-building, and boats remain central to the place. Take the short walk from the town centre to the River Deben and you pass a number of boatyards. Walk along the river and you see many houseboats and pleasure craft moored. But when the boats fall into disrepair, they are not removed - presumably because that would be an expensive and cumbersome process - but are simply left where they stand, to rot on the riverbed, becoming a temporary resting place for birds and other scavengers. The boat-carcasses pictured above, though warped and dilapidated, are still, recognizably, boats. But as you walk alongside the river you see stumps, wood-skeletons, and slimy, huddled heaps: putrefying corpses of boats which are at the very limit of boathood - a picturesque exemplification of the problem that is at the heart of Reza's philosophy. It would be good, one day, to have a photographic record of the various different stages of rotting-boat at Woodbridge.

Photograph by Jon Wozencroft

Interesting Borgesian question...

What could the 'etc.' in this list of influences possibly refer to?

- Neu!,Giorgio Moroder,Kiss,Suicide,Todd Rundgren,Michael Mcdonald,Arvo Pärt,Mötley Crue,Fleetwood Mac etc..

Surely such a list is as bizarre as the taxonomy Borges famously refers to in his story 'The Analytical Language of John Wilkins'. Or surely it is just a joke? Incredibly, judging by the tracks on Kleerup's myspace page, it doesn't appear to be, entirely. The sumptuous, glistening Kate Bush-meets-Moroder-meets-Kelley Polar-meets-Stevie Nicks hit 'With Every Heartbeat' (featuring Robyn) is Kleerup's most renowned track, but also check out the machinic melancholy of the magisterial instrumental 'I Just Want to Make...'; it's the soundtrack for a train journey through icefields, like the Junior Boys if they were suffused with the Scandinavian, rather than the Canadian, winter.

More weird yet wonderful Scandinavian pop here. Check the song 'Tricks' - girlpop with a backing track that sounds like some Fruity-Loopy Grimed-up stab at conjuring up ye-olde-pipes-and-flutes-Tolkienesque-rusticity.

Both tip-offs from Johnny Dark, whose brilliant collaboration with San Serac, Stereo Image, ought to be massive this year, if there's any pop justice.

June 10, 2007

'Where is this Interzone place, then?'

(For readers outside the UK... Alexa Chung and Alex Zane are the inhumanly smug presenters of Channel 4's Popworld, a programme that pursues compulsory trivialization to the point of leering, joyless nihilism. Someone who totally detested pop music and wanted to drain it of all remaining libido couldn't have come up with a better vehicle than Popworld, a kind of cheery-sneering marcabre lab experiment to see how far unmitigated PoMo can be taken. Channel 4's other late-night pop programmes are slightly more earnest, but if anything even more abject than Popworld. They are basically free promo slots for the industry to show off its latest - usually Indie - wares, and they produce the same immuno-response in me as gardening programmes or Formula 1 - I'd rather watch the inane quizzes on ITV Play. Channel 4, where once upon a time you could stumble upon PiL live next to Tarkovsky seasons or Patricia Churchland talking about eliminative materialism next to Art of Noise videos, is now prostituted out to the lowest-common-denominator fantasy projections of slumming-it ruling class producers going further and further downmarket in unseemly pursuit of the elusive under-30 dollar. Strange that anything 'educational' or 'difficult' is deemed to be oppressive and elitist, whereas programmes which explicitly tell people (usually working class) how to dress, eat and clean their houses are perfectly acceptable. It's OK to suggest that someone looks haggard because they have neglected the botox (rather than because they have been doing a miserable job and looking after kids for the last thirty years) but anything even remotely smelling of cultural or intellectual improvement is verboten. I suppose that's democratic materialism for you...)

A reader writes:

- What's most wearisome about the popworld/balls of steel/Friday night project axis is that, for the first time, we have a tv version of 'popism' - a place where everything is trivialised, where the 'nothing is true, everything is permitted' ethos just turns everything into an unholy mush, where the only condition is to be 'in on the joke'. The joke being precisely… what?

So your question 'How many popists are there who didn't go to public school' could be extended to any of the new wave of the television of boredom. How many of the hapless researchers preparing jokes for Alexa went to state schools?

... One final word on the insidious effect of popism on tv - not sure if you've heard the Good Shoes record about Morden (basically, it says it's a shithole). Hardly the last word in sonic invention, but a pleasing, annoying racket if you like that kind of thing.

Lo and behold, there's Alexa (a post on her must be round the corner!) taking the band round Morden, meeting with the tourist office, mugging for the cameras - basically, draining any power the single might've before it's even in the fucking shops! The implications are staggering - you can imagine an alternative history where Paul Weller is made to wear an Eton uniform while Alexa plays a saucy school-mistress, or Ian Curtis on a day-trip to Warsaw with Alex Zane pretending to be a goth ("where is this Interzone place then?")... Or how about Morrissey camping out on the Strangeways roof, while the pair of them play cheery prison guards, delivering him a cuppa?

June 09, 2007

Pomo as physiology

Fascinating interrogation of Davina McCall last week in the Guardian.

- Davina McCall is posing for photos and struggling, it seems, with the range of faces available to her. The TV persona, once sprightly and uncontrived, now shouty and camp, keeps surfacing to corrupt her features, whereupon the photographer pleads for neutrality and she tries with an almost physical effort to suppress it.

McCall as a carrier of a set of gurning, twitching tics, like some leering Jim Carrey monstrosity: idiot reflexivity gone anatomical, her face stolen by a screaming Mr Punch mask which cannot speak except in a circus-barker yell or hyper-histrionic panto conspiratorial whisper-to-camera...

Incidentally, I've managed to largely avoid BB so far this year, perhaps because I had given up all resistance to it and accepted that I would watch it. Perhaps it's only when I make a decision to avoid it that it ends up seducing me, like Death at Samarkand.

- Consider the story of the soldier who meets death in the marketplace, and believes he saw his making a menacing gesture in his direction. He rushes to the king’s palace and asks the king for his best horse in order that he might flee far into the night from Death, as far as Samarkand. Upon which the king summons Death to the palace and reproaches him for having frightened one of his best servants. But Death, astonished, replies ‘I didn’t mean to frighten him. It was just that I was surprised to see this soldier here, when we had a rendez-vous tomorrow in Samarkand.' (Baudrillard, Seduction, 72)

In other reality TV news, how can it be that clueless Cambridge twit Simon has made the final of The Apprentice? Oh, I suppose I've answered my own question. The bumbling, ineffectual Simon - described by Charlie Brooker today as a 'shivering puppy' - was the opposite case to Katie Hopkins. Hopkins' baseless confidence blinded everyone - including the supposedly bullshit-sniffing Sralan - to her actual incompetence. As I argued before, it was the discrepancy between Hopkins' confidence and her limited ability that most galled about her. Sadly, her exit this week - she left when Sugar forced her to admit that she didn't really want the job - meant that the illusion that she is talented (but unpleasant) is preserved. Revelations that Hopkins "went on the show to make herself a Simon Cowell 'Mr Nasty' figure" come as no surprise, but Hopkins' witless put-downs betrayed a cliched level of thought far more limited than that she attributed to the one-dimensional caricatures she tried to ridicule.

Simon Ambrose, however, doesn't need to be confident, because his university is confident on his behalf. His career since leaving Cambridge has been shambolic - but never mind, he doesn't actually have to do anything, because his being to Cambridge means that he is ontologically talented. Going to Cambridge or Oxford is a magic talisman which ensures that graduates are like the Brazil football team - only the good things they do are perceived, everything else is treated as an aberration.

Just for one week, wouldn't it be good if everyone appearing on television who went to Oxford, Cambridge or Eton - presenters, politicians, captains of industry, etc - had to wear a temporary tattoo on their heads (O for Oxford, C for Cambridge, E for Eton)? That would produce some good resentment, I reckon.

No promises, but...

What is it about promising to write posts that guarantees that they won't be finished, or will be finished only after a tortuously extended period?

Is it simply that when something has been promised it becomes something one ought to do instead of something one wants to do? Many of my posts - including some of what turned out to be the most important ones - arose semi-spontaneously, when I had perhaps only intended to put up a link with only a few words of comment. In common with all modes of jouissance, the jouissance of blogging often arises by accident, by the avoidance of an official goal, the thought that 'this isn't what I should be writing about now, but I'll just write a bit more...'

In any case, my plan to have posts up early this week was derailed. Partly by a fabulous few days in London last weekend, so inspiring that they produced a whole set of other virtual posts that seemed more urgent than those I had previously intended to complete, partly because of deadlines and visitors this week. So in a bid to catch up, and to quickly sketch in a few ideas before they are forgotten, I offer the following ragbag set of reflections, which are connected only by the fact that they occurred to me in the period since the last post.

Two interesting interviews with Simon, one at Ballardian, the other, by Bat, at Socialist Worker. (Speaking of Bat, he has a fascinating take on Rihanna's 'Umbrella', which I hope he will post soon - incidentally, at this stage, it's looking very possible that Rihanna may well end up producing my favourite singles of both 2006 and 3007.) There's a great deal of bad resentment about Simon doing the rounds, but I like to think that his success is due, not only to his talent, but also to his grace, reliability and willingness to encourage others. Nice guys don’t always finish last…

’Permission to give Latimer a beating, sir’. A really rather good Dr Who two-parter, by Paul Cornell, concluded on Saturday. The story was adapted from Cornell’s own New Adventure novel. (Throwing up an interesting philosophical quandary…. The New Adventure novels were written in the period after the show had originally been cancelled in 1989 and at the time they constituted what appeared to be the only official continuation the series would have. But now that the Human Nature novel has been adapted, it seems to have been retrospectively demoted to a lower ontological status in the programme’s ‘reality’. Cue all sorts of debates in fandom about whether the novel is ‘canon’ - this usage, rather than the grammatically standard ‘canonical’, is preferred by Dr Who fans – , whether there is a Doctor Who canon of texts which officially belong to the programme’s reality at all – because, unlike with Star Wars and Star Trek there is no official authority which ‘rules’ on which texts do or not count in the official reality – and whether enjoyment can be retrospectively stolen.)

The plot of the two episodes concerned the Doctor transforming himself into a human being - a schoolteacher in a 1913 school, called John Smith - so as to evade a predatory family of aliens. It can't only be me who was crushingly disappointed at the moment when the restrained John Smith gave way to the gurning, overexcited postmodern Kenneth Williams that is David Tennant’s tenth Doctor. If there is a personification of the new BBC, it would be Tennant’s Doctor – at one and the same time, neurotically ingratiating in his desire to please and oh-so-pleased-with-himself smug.

In effect, the conceit allowed Dr Who to temporarily de-Buffyize itself, to dispense with so many of the features that we are told are essential to its continued success, to shuck off all the tiresome popcult references, the hormonally-crazed emotional porn (the love relationship between Smith and the matron was all the more powerful for its restraint), the hectic pace (it was notable that far more seemed to happen in these two episodes than in any two episodes paced at breakneck speed). In becoming a 1913 human, the Doctor became far more alien to 21C culture than he has ever seemed in his tenth incarnation.

Oestrogen-deficiency. Me on Soul Jazz’s Box of Dub…

Bigmouth strikes again...and I've got no right to take my place/ in the human race... Owen is the first off the blocks to express dissatisfaction with the No Future Together event (although Dominic, who didn't attend the conference, inadvertently - but with impeccable, perhaps uncanny, timing - highlighted many of the problems that the symposium gave rise to in this superb post on kinship). The conference was highly stimulating, albeit, for the most part, negatively so, provoking me into a long delayed engagement with Queer theory. (I won't promise to post any more of that engagement here, for fear of giving rise to the hex I described above.) Owen has already highlighted the principal problem as I saw it: the failure to derive from Edelman's critique of 'reproductive futurism' a collective alternative to the Right's 'family values'. The conference - including Edelman's keynote presentation - seemed to evade all of No Future's traumatic implications for theory. Is the problem the appeal to the future per se, and what would it be like to have a type of theory that was no longer anchored to any concept of the future at all? Or is it only 'reproductive futurism' that it is the problem, and, if so, what would a non-reproductive futurism look like? Raising these questions - which I did in perfectly good faith - was, shall we say, not welcomed.

Edelman's presentation of bareback gay male porn as some anti-heroic anti-Christian humbling of a Man already as dead as God was disappointing, to say the least. With his paper, and with the paper by the Chair in Aberrant French Sexualities' (not her real title, but only a slight caricature) we were in an all-too familiar transgressive space that, as Joel Anderson pointed out, Lacan was the very theorist to most effectively critique. The elementary Lacanian question 'for whom are you doing or talking about X?' was evaded. Who is that is scandalised or appalled by references to sexual practices that risk death, and why should scandalising them be the implicit aim? If the goal is not, or no longer, to petition the State for rights, surely there has to be more at stake than a perverser-than-thou desire to demonstrate to a big Other whose existence is at the same time disavowed how naughty one can be? (Daddy, you can’t make me protect myself, it’s my body and I’ll die if I want to…)

Owen is right: the point at which the Queer was paralleled with the child was both deeply unfortunate and revelatory. Again, it is an elementary lesson of Lacanianism that polymorphous perversity cannot be recovered, nor is it present in the human child in any unmediated way. The very moment a baby is born, it screams: i.e. it makes a demand to the Other. All of its activities - especially the most supposedly 'natural' ones - are very quickly tied up in signification. This is not simply to do with the role of language, but the play of approval and disapproval, so that shitting and eating are immediately and inextricably connected to with what pleases or displeases mummy and daddy. To shit is never only a natural process, but also a sign. So being seen to deliberately put one's life at risk, or being seen to smear one's face in the excrement of transgression, can never be simply a matter of devil-may-care abandon. And this dimension of 'being seen to do X' cannot be avoided, especially if you are very pointedly being seen to talk about supposedly unspeakable practices in a university. The pretext of transgressive panto-mummery - if only the fusty old Symbolic weren't there, the pervert could be, like, free to do what he wants, - barely conceals its disavowed reliance on a disapproving gaze. And the tragic impasse for discourses of transgression is that an act doesn't cease to be mummery no matter how extreme, how 'authentic' it is. Even death remains a sign.

The big Other cannot be transgressed away, and the conference also highlighted something that has really begun to grate on me: the incessant appeal in contemporary culture to the 'radical'. When every New Labour neo-liberal 'reform', when every theory in the Humanities, no matter how insipid, has to be touted as 'radical', shouldn't alarm bells be ringing about the impulse to claim radicalism? It's possible, of course, to argue that these ostensible forms of radicalism are not authentic, that there is a real radicalism that all these fake candidates never attain. But why not pursue the opposite route, and stake out a new orthodoxy, a big Other that is not disavowed but acknowledged? (Couldn't one role of concepts of faith and fidelity be to displace the exhausted language of 'subversion'?) (None of the above questions are rhetorical by the way.) The paradox of course is that the big Other's non-existence can only be confronted when the big Other is acknowledged; when it is ignored or overlooked, it insists all the more powerfully.

The child's face is the ultimate ethical trap. Some of the most interesting discussions at the No Future event concerned the Madeleine Mccann phenomenon. Mandy Merck - for me the best speaker at the conference - was excellent on this. I'll try not to repeat points that have already been well made by Antigram, but the coincidence of the 'Maddy' hysteria with the No Future event was highly suggestive. What better example could there be of Edelman's claim that the figure of the child is an unrefusable moral blackmail in contemporary culture? I need hardly say, I hope, that of course the disappearance of Madeleine Mccan is a horrific event; but we are not dealing only with the fate of a little girl any more. The media injunctions about Madeleine Mccan have the apparent form of ethical demands - we should maintain awareness, we should feel compassion - but they have no ethical content at all. Rather, the demand that 'awareness' be raised is a symptom of the persistence in postmodernity of the supposedly primitive belief structure of magical thinking (the idea that thoughts can have a direct effect on reality); and the useless, narcissistic compassion we are invited to feel for the Mccans - how will that help, them or anyone else? - is the piety that is the flipside of media cynicism. It's not only that Madeleine Mccan's face is used to cover up other geopolitical events, as Antigram shows; it is also that the pseudo-ethics surrounding one child's face are used to blind us to systemic injustices that lead to the suffering and deaths of many thousands of children and adults every day. (And the sight of the Pope - who actually could do something concrete about systemic child abuse in the Roman Catholic Church if he wasn't dragging his feet - piously engaging in a thought transference ritual with the Mccan's is really too grotesque to contemplate.)

The divine Daphne.

Edelman’s andro-(ab)normativism – in principle it is not only the male homosexual who can occupy the position of the Queer, but in fact most of Edelman’s examples end up being gay men (Antigone and the Birds are, as far as I recall, the only two cases of Sinthommosexuals in No Future who aren’t men) led me to thinking about du Maurier. As yet, I confess to have only encountered du Maurier indirectly, through the film adaptations of her work. But what films … The Birds, Don’t Look Now and Rebecca. (And what, by the way, of Hitchcock’s relationship to Queer women, since he adapted three of Du Maurier fictions, and one of Highsmith’s?) Rebecca, a film that haunts and is haunted – perhaps most of all by Jane Eyre, its ancestor-doppelganger. Rebecca, which like Jane Eyre and many of Highsmith’s novels achieves uncanny – or would it be better to say queer - effects without any recourse to the supernatural. (A question I want to raise but can’t answer yet: what is the relationship of the Queer to the Uncanny and the Weird?) Rebecca, which can only be placed in the interstices of genre: Du Maurier denied it was a romance, but what else is it? This un-romance which, unlike the classic romance novel, begins not ends with marriage – first there is the sham marriage, Symbolically mandated but existentially and affectively a charade, then there is the true marriage, with the couple destituted, dispossessed of the Symbolic property, Manderley. (A near reversal, or better, a skewing, of Jane Eyre, in which Jane and Rochester, governess and master, first of all live as if husband and wife, without Symbolic mandate and without sex, and can only be officially married only after Thornfield has burned down. In the case of Jane Eyre, the Other woman has to be killed before the marriage can occur; in the case of Rebecca, the Other woman – Rebecca herself – blights the marriage by already being dead.) But isn’t Rebecca a sinthommosexual, as a brilliant piece on du Maurier in the Independent last month, suggested?

- [F]ar from being a demure wife, it turns out, Rebecca was a sexually free spirit who held the bonds of marriage in contempt. We aren't told what she got up to: Max de Winter won't give it a name. But "she was not even normal", he says, savagely. "I don't want to tell you about [those years], the lie we lived, she and I." If he is repulsed, however, Danvers is admiring. Rebecca's close companion and maid for many years, "Danny" is clearly still in love with her. Rebecca "had all the courage and spirit of a boy", Danvers says. "She ought to have been a boy." Rebecca's affairs with men meant nothing, Danvers insists: "She despised all men.... Lovemaking was a game to her, only a game. She did it because it made her laugh. I've known her come back and sit upstairs in her bed and rock with laughter at the lot of you."

- What has happened to Rebecca, this vital, forceful creature who we are told had the face of a beautiful boy, who went through life shaking with silent laughter, thumbing her nose at the world? Before the novel even starts, she has been killed, locked in a box forever - the tiny cabin of her boat - and buried beneath the sea. Du Maurier may have raved "to hell with psychoanalysis", but that's as clear an image of repression as you can get. It fails, as repression fails: the attempt to blot out Rebecca has only made her stronger. Though dead, she still dominates the book. She is the centre around which the thoughts of the others constantly revolve. Even the boat her body lies in is called Je Reviens ("I will return"). Her presence haunts Manderley, where it is felt in every room: the second wife sees her possessions, her taste, as "vividly alive, having something of the glow of the rhododendrons... rich and glowing in the morning sun".

The second wife's growing obsession with Rebecca, which du Maurier claimed was jealousy, begins to seem curiously like desire as the book proceeds. For one, there's a preoccupation with Rebecca's physical attributes, which she cannot seem to control. "Wherever I walked in Manderley, wherever I sat, even in my thoughts and in my dreams, I met Rebecca," she says. "I knew her figure now, the long slim legs, the small and narrow feet. Her shoulders, broader than mine, the strong and clever hands... If I heard it, even among a thousand others, I should recognise her voice. Rebecca, always Rebecca." In a telling episode, she goes on the sly to inspect what had been Rebecca's bedroom, "my heart beating in a queer excited way". Once there, she begins to fondle Rebecca's intimate possessions. She notes that the room smelt "queer" - that word again. At that moment the door opens and in comes Danvers, "triumphant, gloating, excited in a strange unhealthy way". Danvers comes nearer. "Now you are here let me show you everything," she says. "'I know you want to see it all, you've wanted to for a long time, and you were too shy to ask.' She took hold of my arm, and walked me towards the bed. I could not resist her." But Danvers doesn't thrust the wife on to the bed and have her evil way with her, as you might expect. Instead, she talks obsessively about Rebecca. "I did everything for her, you know..." The mood darkens as Danvers describes the night of Rebecca's death, then becomes intimate again: "When Mr De Winter is away, and you feel lonely, you might like to come to these rooms and sit here ... I feel her everywhere. You do too, don't you?"

Though this scene pulses with the narrator's "queer" excitement, there's dread, too, and distaste: far be it from du Maurier to admit to "that unattractive word that begins with L". Danvers, in other words, is a threatening character because she represents what du Maurier thought of as a threatening thing. She, like Rebecca, is "a menace". She is often described as looking dead, a "black figure" with a "skull's face" and "hollow eyes". That is partly because she is, in one sense, a dead woman: her heart is in the grave with Rebecca. Like the second wife, who feels herself to be a ghost, and Rebecca herself, Danvers is a "disembodied spirit", "all wrong".

With all this, it's perhaps surprising that heterosexuality wins in the end. Or does it? After all, Max de Winter and his bride are forced into exile in a foreign land, where they fritter away their time in dull routines, talking about cricket. They lose Manderley, which stands for many things, among them class, privilege, marriage, domesticity, all destroyed, burned to the ground by an enraged lesbian (who gets away scot-free, too, in contrast to the film). In fact, Manderley can be seen as another box: a grandiose box, but a box nonetheless, in which the second wife feels herself to be buried.

We’re apt to read Du Maurier’s distaste for the ‘L word’ as a symptom of the repression of her historical period – just as we are likely to attribute the avoidance of the settling of the question of Ripley’s sexuality in The Talented Mr Ripley as merely an effect of Highsmith not being able to say, in the 1950s, what he ‘really’ was. But it’s equally possible that the refusal to be defined by one (sexual) predicate is what makes Du Maurier and Ripley queer rather than simply gay. Highsmith’s genius in having Ripley married at the start of the second novel, Ripley Under Ground - he and his wife Heloise remains happily married, that is, in a state of contented non-relation, throughout all the subsequent novels - does not definitively settle the question of his sexuality, it keeps it open. And if Ripley cannot be defined by one predicate, neither can his queerness. What makes him queer is some indefinable X that cannot be ‘located’ in any one of his determinate properties…