July 31, 2007

Built to Last

To the splendid opulence of Eltham Palace on Sunday, one of London's hidden jewels recently eulogised by Owen. Like Portmeirion, but in a very different way, the architectural palimpsest of Eltham Palace - 'a 1930s graft onto a 15th century Tudor pile' - is an example of sympathetic modernization. The 'deco rotunda', the 'rooms done in whichever historicist style currently favoured, in this case some ersatz Dutch and Italian bedrooms (with the telephones and radio speakers secreted in imaginative places)', were ostentatiously new - as Owen observes, 'the sinister ambience of the moderne' is everywhere in Eltham Palace - without being violent desecrations.

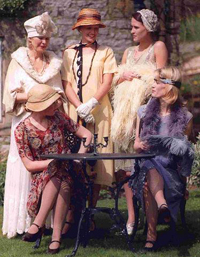

By happy accident, our visit coincided with a show of Thirties fashion organised by the gloriously-named Notty Hornblower of Hope House Costume Museum and Restoration Workshop. Hornblower's obvious love and enthusiasm for the clothes set her far apart from the tight-lipped smugonautics of the typical - shudder -'curator'. Her restorations of the dresses, coats and nightwear amounted to acts of reverential hauntological summoning. Her intimate knowledge, not only of the fine details of the clothes themselves, but also of their owners and their personal histories, brought a whole era of women's lives and preoccupations back to unlife. Naturally, not all of the owners were known, since many of the clothes had been rescued from charity shops, jumble sales or other anonymous sources. She discovered one especially stunning dress, whose detail was all in the sleeves, unceremoniously stashed in a box of oddments, the deco sleeve drape over the side, almost as if it were beckoning to her, the dress quietly inviting its own reconstruction. In the cases where the owner is not known, there is only speculation, spectrality...

- In another apartment, not far away, in Kensington, he opened a wardrobe and found half a dozen pure silk Fortuny dresses that must have formerly been worth a few thousand pounds. They were not hung, but twisted and rolled into skeins to preserve their pleats. These were said to be so fine that one could pass them through a wedding ring, and as he lifted them, he marvelled at their lightness and the soft shining of their subtle colours in the dusty illumination from the windows.

In this same apartment he came across photographs of the woman who must have worn these dresses as a young girl. She was very slender and typically thirties in style - short hair, pale face, dark eyes and lips. The photos showed her standing among her friends in the gardens and drawing rooms of the well-to-do through the years of changing fashions - the austerity of the forties, the grey fifties, and as a good-looking mature woman in the early sixties. After that there were no more photographs, though she must have lived in this apartment for long afterwards.

- John Foxx, 'The Quiet Man'

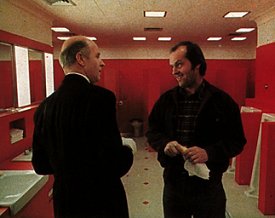

To see these clothes amidst the faux-Hollywood finery of Eltham palace, with elegant thirties tearoom pop wafting in the background, was to experience a double nostalgia, a nostalgia for modernism that had already been reflexively worked through in the 70s, in Roxy, Pennies from Heaven and The Shining. Walking around the long-vacated apartments of the Cortaulds, you half expect to come upon an 'obsequious manservant' of the Delbert Grady type, a relic of a disappeared social hierarchy, a ghost who doesn't remember that he is dead ('it's all forgotten now...') , delivering drinks to deceased masters who will never receive them. Yet Eltham palace is rich in its own wealthy ghosts and, as so often in English Heritage sites*, you imagine the kind of British film that it is impossible to conceive of being made now: a lavish existential epic anatomizing the heartaches within all those leisure class dreamhomes... (Eltham Palace was actually used in the TV adaptation of Brideshead Revisited but, as Owen when we talked after my visit on Sunday, surely Eltham Palace deserves better than that...)

|

Jameson's comments on the nostalgia of The Shining are worth recalling here, since they are highly pertinent to current discussions of class envy:

- The nostalgia of The Shining, the longing for collectivity, takes the peculiar form of an obsession with the last period in which class consciousness is out in the open: even the motif of the manservant or valet expresses the desire for a vanished social heirarchy, which can no longer be gratified in the spurious multinational atmosphere in which Jack Nicholson is hired for a mere odd job by faceless organization men. This is clearly a "return of the repressed" with a vengeance: a Utopian impulse which scarcely lends itself to the usual complacent and edifying celebration, which finds its expression in the very snobbery and class consciousness we naively supposed it to threaten.

In retrospect, The Shining, rather like Pennies from Heaven and the early Roxy, can be seen not as an example of postmodernism, but rather as a case of pulp modernism. It was still an interrogation of the pull of nostalgia rather than an exemplification of the nostalgia mode; it was still awake, even if its eyes were growing heavy-lidded; still in history, not yet given over to the nightmare of the end of history from which we are yet to awake. Deliberate anachronism means that, for all its soft focus sweet sickness, The Shining's longing for the past never produces a seamless simulation. The Shining's Gold Room is ostensibly set in the Twenties, but is soundtracked by music from the Thirties - by Ray Noble and Al Bowlly, who feature so heavily in Potter's work, as it happens. And here is the dishevelled Jack, Oedipus at the end of History, dreamer dreamt by Old dreams, dreaming of Good Old Days where a man knew his place; here he is, a dressed-down mess, drink spilled down his oh-so-inappropriate lumberjacket. He does not fit in - sartorially, existentially, temperamentally. He's not the right sort of chap at all...

Unmask! Unmask!

In the popular modernism of those thirties fashions, we see an embellishment, a beautification, of the everyday. But at the end of History we all look like Jack, a.k.a. the Last Man, a.k.a. Oedipus, the avatar of capitalist realism. (Capitalist realism, the myth of no myths, is the dullest of masques, where Capital calls the tune, and the revellers imagine that they are their faces.) Life is not even a dress rehearsal now. We tramp around in track suits through the artfully arranged relics of previous events, beliefs and rituals, forever the consumer, the spectator, of (past) stability ... ours is world that's constantly changing. (So this is the atermath...)

Many of the clothes in Lotty Hornblower's thirties collection, she said proudly, are still in immaculate condition after 70 years. (Amazing, isn't it, how they managed to produce commodities of such durability without Quality managers, mission statements and 'core values'?) It was a period of capitalism still naive enough to build things to last... by contrast with the inbuilt obsolescence of the OedIPod at the end of history, where nothing lasts, and only trash keeps returning...

* I fantasise about a collaboration with English Heritage called English Hauntology, in which the sites are used for some Weird confection of fiction, film and music ...

'If the proletarian should speak, we should not understand him...' (aka grunts, snarls... and curses)

This just in from Dominic (via email):

- HAMM: Yesterday! What does that mean? Yesterday!

CLOV: (violently). That means that bloody awful day, long ago, before this bloody awful day. I use the words you taught me. If they don't mean anything any more, teach me others. Or let me be silent.

(from Endgame)

Something that crops up in E.M. Forster (Howards End) and also Virginia Woolf (although I can't place a reference) is the notion that if ordinary clerks like Leonard Bast (one of the most condescended-to figures in literature) should attempt to improve themselves by exposing themselves to "high" culture, they would eventually make the horrifying discovery that beneath all of the elevated sentiment there is an esoteric message of profound spiritual desolation, which if

haplessly uncovered will terribly maim them. The proper owners of high culture are shielded from this radioactive kernel of anomie by their ownership of nice country homes, etc, but if they ever let on that life is essentially meaningless and tragic, morality is a lie, not to be born is the best for man and so on, then dire social consequences will surely ensue. (Burroughs: bring it on). The exoteric meaning of high culture is that it is improving, ennobling, a worthy object of aspiration, but the esoteric content is the total destitution of all of these values (and the privilege of being the insider who *knows* they are destitute, and laughs at the pretences of those who still aspire to realize them: thus the ruling class disdain towards any sort of passionate cultural commitment - to them, culture's a bunch of old stuff they keep in their attics, like the picture of Dorian Grey...).

Racist ethnologist of the "underclass" Theodore Dalrymple amusingly blames the Bloomsbury intellectuals for infecting the masses with their bohemian fecklessness - again, it's a matter of divulging the nuclear secrets of high culture and thereby corrupting the commonsense morality of ordinary folk.

Wittgenstein's version of Caliban - "if the lion could speak, we should not understand him": a form of words is bound to a form of life, outside of which it is unintelligible except perhaps as grunts, snarls...and curses.

UPDATE:

Reader Scott Duguid responds:

- Perhaps [Dominic was] thinking of Charles Tansley from Woolf's To The Lighthouse. Tansley is the novel's whipping boy - Woolf says as much through Lily Briscoe. Below is the relevant passage (and, in terms of pov, a somewhat complex one it is too). While this affirms the pattern noted in your post ("all she felt was how could he love his kind who did not know one picture from another" - is it the arriviste Tansley, or "his kind" whose aesthetic discriminations is being impugned here?), this view of an upsetting, upstart class-consciousness is also mediated by Woolf's feminism. Tansley is not simply a class whipping boy but also provides the alibi for Lily's class as regards the role of women. Woolf's lower-middle class upstart is conveniently the prime example of the male as intellectual bully of women.

This is, of course, one of the hidden tricks of a strain of contemporary anti-class discourse too...

And yet, there is the education of the sister (which resonates with the foregoing "brotherly love"). In my reading of To the Lighthouse (which is not recent), I seem to recall this passage as being one of the few where any reflective critical light is thrown on the novel's wider class assumptions.

If I get round to reading the piece in last weeks guardian about Woolf's treatment of her maid, perhaps I'd have more to say...

'Her going was a reproach to them, gave a different twist to the world, so that they were led to protest, seeing their own prepossessions disappear, and clutch at them vanishing. Charles Tansley did that too: it was part of the reason why one disliked him. He upset the proportions of one’s world. And what had happened to him, she wondered, idly stirring the platains with her brush. He had got his fellowship. He had married; he lived at Golder’s Green.

She had gone one day into a Hall and heard him speaking during the war.

He was denouncing something: he was condemning somebody. He was preaching brotherly love. And all she felt was how could he love his kind who did not know one picture from another, who had stood behind her smoking shag (”fivepence an ounce, Miss Briscoe”) and making it his business to tell her women can’t write, women can’t paint, not so much that he believed it, as that for some odd reason he wished it? There he was lean and red and raucous, preaching love from a platform (there were ants crawling about among the plantains which she disturbed with her brush—red, energetic, shiny ants, rather like Charles Tansley). She had looked at him ironically from her seat in the half-empty hall, pumping love into that chilly space, and suddenly, there was the old cask or whatever it was bobbing up and down among the waves and Mrs Ramsay looking for her spectacle case among the pebbles. “Oh, dear! What a nuisance! Lost again. Don’t bother, Mr Tansley. I lose thousands every summer,” at which he pressed his chin back against his collar, as if afraid to sanction such exaggeration, but could stand it in her whom he liked, and smiled very charmingly. He must have confided in her on one of those long expeditions when people got separated and walked back alone. He was educating his little sister, Mrs Ramsay had told her. It was immensely to his credit. Her own idea of him was grotesque, Lily knew well, stirring the plantains with her brush. Half one’s notions of other people were, after all, grotesque. They served private purposes of one’s own. He did for her instead of a whipping-boy. She found herself flagellating his lean flanks when she was out of temper. If she wanted to be serious about him she had to help herself to Mrs Ramsay’s sayings, to look at him through her eyes.'

UPDATE 2

From reader Wedge:

- Jeeezus - I remember using that exact 'Endgame' quote in university (comparing it with '1984' as a domestic - as opposed to geopolitical - dystopia). Spooky.

Also weird is that Beckett is a prime example of 'high culture' finding it's way to 'the masses'. The BBC had a long season in 1988 in tribute to Sam Beckett. It was one of those things I didn't exactly 'love', but it held enough fascination (and mystery!) for me to feel like I could access a diffrent cultural world. It put my brain in certain directions.

Ironically, I had lecturers who regarded this Reithian purpose with disdain (smug 60s kids the lot of 'em). Well, I suppose there's no way you'd get an extended season devoted to Beckett on terrestrial TV anymore (or even Welles, Chaplin or Lang as you once did). Or a month of programmes devoted to May 1968 as C4 did in the late 80s.

The dumb-down of TV and pop discourse has been a huge blow to popular culture in general. Pretension can be a good thing, if it involves its audience 'thinking' above its 'station'. Watching Potter, or even reading 'NME' or '2000ad' could once make a 13-year old feel he was on an intellectual adventure of sorts, a junction that could lead to something 'higher'. Not something you could say for the hollow ghosts those publications now exist as.

But then, I'm still bitter that our patronising 'yoof' culture BBC means that Om Puri wasn't cast (or wouldn't even be considered) as Dr. Who...

July 30, 2007

"You taught me language ..

.......and my profit on 't / Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you / For learning me your language!" (Caliban in The Tempest).

Collage of anonymised class correspondence:

1.

- I grew up in a Daily Mail nightmare (council flat, single parent, mixed-race, erratic employment for relatives etc.), but as the 'bright' one managed to end up with a degree after absorbing a whole dollop of high theory and intellectual excitement that seems to have little use in the 'real world' (and is slowly being erased from the academic one, by the look of it).

Ironically enough, the only 'proper' full-time job I've had since then has been in the same godforsaken street I grew up on - helping 'disengaged' youth (I went to university as far away as possible). After years of having it pumped into my head (by family) that I could 'escape' my surroundings, I could only find a decent salary by 'regenerating' them...

I too find it difficult to relate to people I grew up around (nothing to talk about, unless I want to be seen as a crank). My more middle-class peers/colleagues seem unwilling to accept their prejudices when it comes to this community. 'Gentrification' has left me hovering around the uncomfortable sides of the fence. I know why 'locals' hate the 'carpetbaggers', but I still end up hanging out (with increasing discomfort) in their gated enclaves; talking about 'the scallies' who (to them) seem to be waiting to attack at any minute... often time to make my excuses and leave the dinner party, exhibition opening... whatever exclusive space they've put a moat around for the evening.

Since graduating, I've also been struck by the absolute lack of critical thinking among the supposedly 'cultured' elite - they're more gullible to any fad or fashion than your average 'chav' teenager... and god help you if you're 'negative' (about anything - from gadgets to rip-off restaurants). It's a given than liberal lip-service is given to race, sexuality etc. but class? That's a paradigm that New Labour have shifted... you can be 'concerned' for the 'socially excluded', but can also demonstrate contempt for anything they actually do or say.

I find as I get older, my closest friendships/relationships are in that 'interzone' of other working-class autodidacts, disillusioned educational aspirers, 'scally mystics' (a term given by a colleague in a similar situation); or well - educated 'downshifters' whose middle-class parents are terribly disappointed by their failure to be in the home-owning professional class (the last group bring their own set of complex tensions to the table - it's hard to resist seeing their slide down the ladder as more psychological than circumstantial). I also find that the 'youth' I easily relate to tend to be self-taught 'nerds' (although their nerdish persuits seem more technologial than cultural these days). It's like I'm stuck between two languages that I can't quite get the hang of.

The Blair era to me is a period of being 'put back in my place'. The summer of 1997 (where the deaths of Diana and free higher education seemed connected, as I graduated into minimum wage service) was a restoration of sorts. Personally, I think we could do with another Major-style recession - nothing like mass unemployment and repossessions to bring down barriers (and piss on the current levels of middle-class smugness). People (well at least young people) seemed just a little more adventurous and socially fluid fifteen years ago...

2.

- When your parents are themselves educators, the discursive continuity between school and home reaches comic proportions - we frequently had to remind my mother that she was using her "teacher" voice on us again...

3.

- What your post proved … is how talking about class provokes the middle class so much. They drag out the usual 'chip on your shoulder' accusations.

4.

- Your recent articles on class consciousness (or the lack thereof) and the confidence differences between those educated at private schools and those in state-funded rang true to me and echoed something I had noticed. I recently graduated from a high school in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a city almost infamous for being working class and "down-to-earth." For all four years of my high school education, I was part of the forensics/speech and debate club. My main category was Student Congress which aimed to replicate either of the houses of the United States Congress. It was about as terrible as it sounds. The sheer amount of hollow politicking involved was amusing at first, but quickly became tiresome. Beyond that, the arrogance of some of the members was astounding, especially as most of it was unwarranted.

However, there was a group of students who were arrogant, but not offensively so. Their arrogance was backed up by confident, intelligent speeches. They seemed to carry themselves with a special sort of dignity. These were students from a particular private school in the area. Perhaps it is worth noting that many of them had a strange, New England accent which reeked of affluence and sounded very out of place in Pittsburgh, though the private school was not a great distance from the city itself. Not every student from this school had the accent, and not every one was a great speaker, but the best speakers almost always came from this particular school (and the two best had the accent); furthermore, this school seemed to produce an above-average amount of superior speakers.

For a long time, I considered myself middle-class "since I hadn't experienced any material hardship, and I was interested in books and writing," ("Epistemic Privilege of the Proletariat") but meeting these students showed me that I certainly was nowhere near the top. Nor could I ever be; I simply lacked the confidence that these students possessed. Perhaps it is also worth noting that the students from this particular school were not mean, as so many others were; on the contrary, some of them were very amiable. They did not need to be mean and claw their way to the top. They were the best, and they knew it.

I cut my long hair, I typed up my speeches ahead of time, I researched them more. And I fell further behind. I switched my event to Prose, where I could perform a reading of a particularly gruesome passage of Nausea as a sort of indirect revenge. I didn't do so well, there, either, but such is life.

I am, admittedly, a bit resentful. These students were accepted into the schools (the Ivy League but it may as well be Oxbridge, no?) that I was encourage to apply to (by parents, peers, guidance counselors and the schools themselves) and from which I was rejected. I am excited to attend the college in which I did eventually enroll and do not at all regret those rejections or my eventual choice. However, the rejections themselves, and the entire process (why bother interviewing me if you're all going to reject me, you bastards?) left an indelible and sour taste in my mouth. Nor, am I sure, is class the only thing that separated us; they were better speakers and probably had better grades, and more extra-curricular activities, etc. But your articles, and the articles of your colleagues in the "blogosphere," (Infinite Thought, especially) helped me to organize my thoughts on these issues and decide that, ultimately, if there is anything separating the Low from the High, it is not money (which can be gained or lost) but a sense (innate? developed? both?) of confidence that, frankly, I lack and they have.

I hope that this did not sound like (too much of) a whine, and I hope that it contributes somewhat to the testimonials you have on this issue.

5.

- It's only now, at the age of 33, that I realise quite how much the transition from the working class to my present 'privileged' status (in terms of education, certainly not material worth!), has really cost me, and countless thousands like me. Certainly working in the media, a supposed meritocracy, one still feels pitifully alone - and I got a first class degree from Cambridge for Christ's sake.

…

I went to see Hoggart speak once, and the question of feminism came up. 'You're onto a dead duck there love', was his dismissive, and no doubt deliberately provocative, answer. Stupid of course, speaking as a male fascinated and transformed by feminism. But identity politics have really done fuck all for the working class, nada, zilch, zero. So interesting that the writer Hari Kunzru, in an interview on BBC World, really laid into his interviewer when they began to warble on about the 'post-colonial' experience, bemoaning the absense of 'class' in all debates. Hence, of course, the horrors of laying into 'chavs', the only acceptable form of racism.

But the big worry, of course, is what's the alternative? So fascinating, your post about the sense of discontinuity between home life and school life for the working class. But while one can feel like Caliban (and I am certainly getting angrier as I get older!), would I switch back? I had a quote from Burroughs scrawled on my wall at home (I must've been a fun child to raise) - 'Bomb Your Bus Stops'. Resentment is a worthwhile point of entry, but... what then?

July 27, 2007

The Dulwich Horror

The Dulwich Horror - H.P. Lovecraft and the Crisis in British Housing

An exhibition by Dean Kenning

Launch evening: Friday 27th July 6.30-8.30 2007 All welcome

Exhibition runs: 20th July to Sept 2nd 2007

window exhibition, viewed from the street 24hrs

Closing event: Sept 2nd 4-7pm, performances. All welcome

A limited edition catalogue associated with the exhibition will be available for sale, with a text by John Cussans.

Image : Camberwell Road SE5, CTHULHU by Dean Kenning, in situ.

The outside walls of rented accommodation constitute a vast advertising billboard for Estate Agents. They appear without warning. TO LET, LET BY - they never seem to come down. If you live in rented accommodation, your home has been branded: you are a temporary occupant subject to the authority of the property owner and his agent.

For The Dulwich Horror TO LET signs across London will form the canvas onto which Dean Kenning will paint images representing the supernatural and monstrous entities from H.P.Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos. Horrible alien beings such as Yog Sothoth, The Outer Ones, and Great Cthulhu himself are famously beyond description (the sight of such creatures would drive any human over the edge of insanity). Nevertheless, Kenning will have a go.

July 20, 2007

Reason wept

OK, I'm supposed to be going on holiday to Wales until next Friday.... but no doubt I'll manage a post or two when I'm there.

Things have been very busy here, and one consequence is that I'm very behind on correspondence (a situation that going on holiday won't help). So apologies if you've mailed me and I haven't responded, I'll do my best to catch up as soon as possible.

In the meantime, this says a great deal about the unreflective assumptions and stupidity of the middle mass...

(And if you haven't read em yet, check Infinite Thought and Dominic on the Class Thing...)

July 18, 2007

Sub specie aeternitas

Has anyone noticed these lines in Rihanna's 'Umbrella', which, I swear, gets better with every listen?

- You're part of my entity/ Here for Infinity...

Meanwhile, Rihanna in hyperstitional-inducer of bad Brit summer shock.

(And since everyone digs Rihanna now, just a reminder of this...)

July 16, 2007

Epistemic privilege of the proletariat

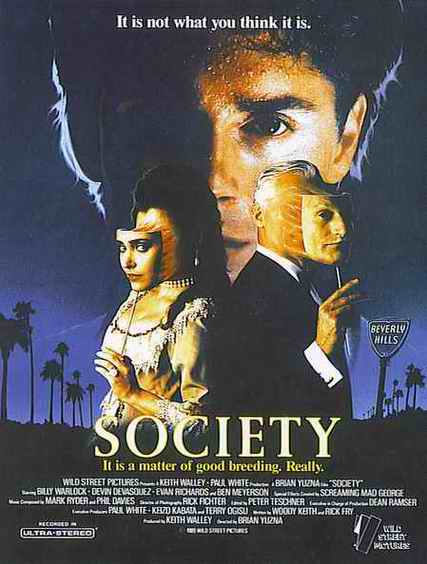

(Image shamelessly plundered from Dejan, who reminded me of the excellent Society, more on which very soon.)

Thanks to everyone who responded, with observations that were captivating and sometimes very personal observations, to the post on class confidence, either via email or on their own sites. The personal very obviously is political here, though, and the sharing of such experiences is always valuable because it shows that they are structurally, not individually, determined. As to other responses - well, (working class) Supernanny knows best, and infants having a tantrum should not be given any attention, especially if they have been indulged in the past.

By email, Kim wrote:

- For me, I'm working class, no high school education, a bachelor's degree that I got from UC Berkeley on scholarship, I spent my teen years in the sex industry, and now I work a regular day job and spend what little free time I have -- when I'm not working or parenting -- writing, making un-trained art, reading, going to movies and thinking about culture in a way that's way outside my class or education. So the combination of my self-taught cultural capital, my class background, my outsider status as a former sex worker junkie loser leaves me pretty much alienated from everyone. I feel horrible around privileged cultured academics and when I'm around working class people I have nothing to talk about. I never even knew what class was and how it was making me so miserable while I was at Berkeley until long after I finished going there.

I never even knew what class was and how it was making me so miserable while I was at Berkeley until long after I finished going there. My coming to class awareness was similar; indeed, before I went to university I believed that I was middle class, since I hadn't experienced any material hardship, and I was interested in books and writing (although as Dominic sagely pointed out, geeks are always in a minority, no matter what social class they are in). It is only by being 'projected out of my class', as one of my lecturers at Hull put it, that I became aware of my class position. Naturally, 'being projected out of your class' means that you only retrospectively aware of your previous position - now you belong nowhere, you are permanently exiled from your class of origin, but you are not yet accepted in the Master Class, nor sure that you want to solicit such acceptance. The angst and alienation that this position of anomie produces is not especially interesting; it is as generic as the self-loathing/ sense of entitlement exhibited by the Masters. What is valuable about it, however, is that it denaturalizes class, changing class expectations and behaviours from a series of unthought presuppositions and default behaviours, to a visible structure.

The importance of these unthought presuppositions is one reason that I disagree with Steve Shaviro's claim - made during a highly eloquent and powerful post - that There is nothing besides, nothing outside of, experience.

My objection to this is in part a Kantian one: in addition to experience, there are the structural pre-conditions of experience, and surely any transcendental materialism must centrally involve an investigation of the structural pre-conditions of experience in class society.

I do not waver in any way from my previous wholehearted support for Deleuze's claim that all arguments from experience are bad and reactionary. That is why I would never make any such argument. But, as Steve suggests, there is a difference between an argument which appeals to experience as some ultimate authority, and an argument which uses experience as an illustration. Political and psychoanalytic theory which cannot explain experience is self-evidently vacuous. The great appeal for me of theory - and of love songs and fiction - is that they allow me to escape from my own experience, to re-frame what was previously experienced as a natural fact into a structural effect. As Brecht and Dennis Potter appreciated, it is only those experiences which distance us from our ordinary, habituated experiences that are politically potent.

But the working class never experience their own lives and behaviours as natural or normal in the way the dominant class does. The encounter with the education system immediately makes working class people aware that their use of language differs from - i.e. is inferior to - the 'standard'. As Basil Bernstein's work on elaborated and restricted codes demonstrated, the working class child experiences the classroom as a break from its experience outside school: the language that the teacher uses will be different from that used by its family or peers. The dominant class child confronts no such ontological breaks, since it experiences school and the home environment as continuous, sites in which the same types of language is used. This experience of double consciousness is the beginnings of process of politicization. In epistemic terms - i.e. in terms of knowledge of the true nature of the social - the subordinate group is in the privileged position precisely because its experience is incommensurate and discontinous, precisely, you might say, because it experience is not (a consistent or quasi-natural) experience at all. It encounters the social field not as some natural(ized) home, but as a series of irreconcilable antagonisms and discrepancies. But this sublime and traumatic 'experience of the unexperiancable' is an encounter with the social field as such - which, in class societies, is not contingently but necessarily and inherently distorted by class antagonism. The working class becomes the proletariat when it recognises this - when, that is to say, it begins to dis-identify with the 'class fantasy' which has kept it in its place.

Of course all experiences presuppose an element of the fantasmatic but that gets us nowhere, unless we believe that all fantasies are the products of an individual's pyschopathology (i.e. if we were adopting the kind of anti-Marxist methodological individualism that Deleuze and Guattari rightly excoriated in Anti-Oedipus, and which put many of us off psychoanalysis for years). What needs to be accounted for is why certain groups have the 'fantasy' of being inferior (and why certain groups have the 'fantasy' of being superior). I place the word 'fantasy' in inverted commas here because, surprise surprise, in the case of the working and ruling classes, the 'fantasies' of their social status correspond with their actual position in the social hierarchy. But we must go round the whole loop here: there is no neutral social reality beyond fantasy, and the class structure can only persist so long as people act in accordance with their class fantasies.

Class fantasies are indivisible from the economic. I hasten to point out here that the economic is not a Marxist concept; it is, rather, the pre-eminent category of capitalist realism. It is political economy that is the crucial Marxist notion - a notion that, as both Karatani and Zizek have observed - is in some senses unthinkable under capitalism. But we can see the indivisbility of politics and economics, of affect, belief and class position, very clearly in relation to attitudes to debt. The working class traditionally abominated debt, whereas the middle classes have always understood that you must 'speculate to accumulate', that money borrowed is not a fixed substantival sum, but a mutagenic agent that can be induced to work and grow. That distinction corresponds exactly to the distinction between payment capital and investment capital. Because of a whole set of beliefs and perceptions, the working class tend to treat money as payment capital, as something, that is to say, which is earned and then either spent or saved. The idea that you take on debt in order to make more money, that money does not have an absolute but a differential value, remains opaque. Of course, the exigencies of late capitalism require that the old working class antipathy towards debt has been removed; yet, working class debt is far more likely to come from treating money as payment capital (e.g. running up credit card bills) than from using it as investment capital (e.g. university tuition fees).

I will end now - though there is far more to be said - by echoing Steven's claim that it is grotesque to blame the victims of class warfare for their psychic scars To insist that inviduals are responsible for their own position as a subject is not only the mantra of neo-liberalism, but of therapy par excellence, and exactly what I had to resist when I was undergoing CBT. In a paradox that Althusser and Spinoza would appreciate, however, it was only when I was able to see many of what I had previously thought of as individual feelings of inferiority as structural effects that I was able to claim responsibility for my own position as a subject. Which is why I hope that Dejan was right, when he argued, in Steve's comments boxes, 'if it is true that Lacan felt the subject should take responsibility for himself, because I only ever heard him saying the subject should take responsibility for his symptom - k-punk took on psychoanalytic responsibility par excellence for himself when he acknowledged (made conscious) the psychological motivation of his resentment against the ruling classes.' I certainly aimed to do so.

_________________________________________________________________

By email, Hessian Pepper notes:

- Oxford University allegedly laments its problems attracting students from low-income backgrounds, yet as recently as five years years ago 'chav' themed college discos were very popular. An Eton educated colleague asked me whether I knew what a 'chav' looked like, since I'd been to comprehensive school. He claimed, somewhat proudly, never to have been in contact with one himself. The disgusting sight of these overprivileged imbeciles mocking and imitating modern poverty in Kappa and gold jewelery was magnified by the sight of the few from genuinely poor backgrounds following their lead.

July 10, 2007

The long green light of a July afternoon

A profoundly moving moment for me: the private view for the Retro/Future exhibition at Fulham Palace last week, which has recently converted into a very convivial art venue... John Foxx playing treated piano over a recording of Scanshifts reading 'The Quiet Man'. Introducing the piece to the audience, John describes this as an attempt to re-construct what Scan and I had done with the story on 'londonunderlondon'.

Profoundly moving, also, because I first read the story when I was only about fourteen years old and it affected me greatly: a pre-echo of London, all the place names carrying a hauntological charge even before I had visited many of them. I read the story then, but talked to no-one about it - for about twenty years, until Scan and I started working on 'londonunderlondon'. Scan responded to the story much as I had, and his reading of it is perfect; he achieves a tone of fascinated distance which draws out all the uncanny emotion in the text, the strange poignancy of old photographs and films, 'all these characters of his past moving in old daylight, waving and smiling and moving on', London as a city of spectres, a hidden connecting corridor of quiet places, of numinous sites where mourning, melancholia and subdued rapture can occur:

- He felt as though there were someone standing next to him, a woman. He could feel her warmth through his shirt, seemed to catch a hint of perfume. He dared not turn to look because he felt that even a small movement would dispel the achingly beautiful sensation, and he did not want that. So he stood alone in that room in the deserted city as the warm darkness fell, remembering the faint rumble of underground trains passing beneath his feet, music from distant radios, voices, old conversations, feeling the radiant closeness of someone intangible and gone.

Gratifyingly, the audience seemed to be rapt.

John explains to me after the piece is finished that the gorgeously distended, decaying sustain effect on the piano is achieved through a reverb unit. 'It forces you to play slowly,' he says. It forces you to listen slowly, too; to discover slowness as a speed, to suspend urgencies on a flatlined, anti-climactic, plateau: 'an unusual state amidst all this rush and ambition'.

The previous week, as Scan records the text in a studio in Ealing, John and I talk about Iggy Pop's appearance on Jonathan Ross - a sixty year old man grotesquely aping the swagger of an eighteen year old - while Vertigo is playing silently on the DVD player. We agree that there was something almost sublime about Iggy's act; it fascinates even as it repels. The contrast with James Stewart , a romantic lead in his forties, is instructive. Where have all the adults gone?

The Fulham Palace show continues until the 21 July. Some beautiful prints fromCathedral Oceans, the DVD of which is playing on a loop, are on show.

July 09, 2007

The ghosts of boats

As a sequel to this, here are some more Woodbridge boat-spectres. Note how some of them are merely traces, the outlines of a boat whose original physical substance has all but disappeared.

Photographs by Bacteriagrl.

July 08, 2007

Punishment enough

Well, a great deal has happened since I last posted - never fear, I've been far from inactive and I hope to be able to share some of the fruits of the past couple of weeks here very soon.

What I must mention first of all is the Tent State University event at Sussex. This was a genuinely autonomous event, organised by students themselves. By wonderful contrast with the necrotically over-prepared regimentation of the typical academic conference, the provisional nature of Tent State, the fact it had no official web presence and a mutable programme, meant that it had an improvised freshness and a fugitive urgency. Simply by pitching a tent on the lawn in front of the library and following a programme of collective auto-didacticism, the event posed questions about access to education and the possibility of anti-capitalist dissidence. Initially, the neo-liberal university authorities sought to block the event. Organiser Andres Saenz De Sicilia, who had kindly invited me, wryly observed that if Tent State had been a gender or anti-racist event, there would have been no problem, confirming that insight of Jameson's I am so fond of citing: it is not 'particularly surprising that the system should have a vested interest in distorting the categories whereby we think class and in foregrounding gender and race, which are far more amenable to liberal ideal solutions (in other words, solutions that satisfy the demands of ideology, it being understood that in concrete social life the problems remain equally intractable).'

When, in the very interesting discussions after my talk, I argued that it's hard to imagine a website which would demonise women or racial groups in the way that something like Chavscum.com denigrates the working class, someone objected that the gender equivalent already exists, in the form of the likes of Nuts and FHM. I'm not sure that the parallel between Chavscum and lad mags is very compelling, however, in part because there are very vocal critiques of soft porn, whereas Chavscum seems to escape censure to the point where it is respectable (with Chavscum's webmaster occasionally being cited in the media as if he were a serious social commentator, rather than the proprietor of a hate site). The fact that there is no offence of 'classism' on the statute books is significant; not because anti-racist or anti-sexist legislation have succeeded in eliminating racism or sexism, but because it shows that class is not symbolically registered in the cultural-juridical reality of late, late capitalism. I hardly need add that this is no accident.

I would like to return at this point to the issue of class confidence raised both here and at Infinite Thought a while back. Dominic's remarks (cited on I.T.) are so germane that they bear repeating here:

-

Public schools instil social confidence; the Winchester and Eton boys I encountered at Oxford seemed - to me, at least - astonishingly socially assured. They were also without exception self-loathing headcases, but I suppose that's the price you pay.

Quite so: class power maims at precisely the same moment that it confers its privileges, which is why, in my experience, so many members of the ruling class resemble Daleks: their smooth, hard exterior contains a slimy invertebrate, seething with inchoate, infantile emotions. Dominic is quite right to insist on the distinction between inner phenomenological states and social confidence. The ruling elite will often be in states of profound inner turmoil (which states they often believe are terribly interesting, even if they are tediously generic); yet this doesn't affect their social confidence a jot. The behaviourist philosophy of Gilbert Ryle may prove surprisingly useful if we want to understand how this is so. Ryle's dismissal of the 'ghost in the machine', his claim that there was no inner entity corresponding to the Cartesian notion of mind, might well have been polemical overstatement, but his emphasis on the external and behavioural quality of mental states is essential to understanding how class power operates. As Dominic goes on to establish, confidence consists in an ability to comport oneself in certain ways and to understand the rules of comportment:

-

I think that at the highest level the question you're addressing is simply that of social privilege; what the wealthy have is wealth, ease and a sense of entitlement which suffuses as much as they can control of their social environment, including their schooling (although this may introduce artificial privations for the sake of "character-building"). They have a general expectation that things will go their way, and that any hardships or obstacles they may encounter en route are really only a sort of a game ("this person in this university / job interview is putting me down in order to see if I can shrug it off, rally and come back at him with something; the cut-and-thrust of the tutorial / trading floor requires that one not be an over-sensitive crybaby" - understanding that these are the rules makes a *huge* difference).

Social confidence is not based on achievements but on intrinsic ontological status: the ruling class are taught to see themselves as essentially talented and intelligent, irrespective of either achievements or failures. (Witness the forlorn but indefatigable figure of twice-bankrupted Rory on this year's Apprentice for an example of this syndrome). Hence Oxbridge types will happily call themselves novelists even if they have never written a novel, or curators even if they have never curated any events. The working class, meanwhile, tend to be more existentialist, believing that status has to be earned, and continually earned. One of the tensions that came up when I had Cognitive Behaviour Therapy was over precisely the issue: I refused to accept that I (or anyone else) had intrinsic value. I am valuable only insofar as I do things, or as Sartre puts it in Existentialism is a Humanism, 'You are nothing else but what you live'. My therapist argued that this is a highly risky position to hold, which makes one prone to depression. But better that hell than the empty certainties of ruling class confidence.

The opposite of social confidence and its attendant sense of entitlement, its urbane at- homeness-in-the-world, is a sense of inferiority, a constant worry about whether one should occupy certain spaces, the quietly panicky conviction that 'surely they can see that I don't belong here'. A sense of inferiority is so much a part of the background noise of my existence that until really quite recently I had tended to assume that it is a universal feature of human experience. That sense of - inherent, ontological - inferiority wasn't something that I railed against; rather, it was so naturalized that it was barely noticed, but constantly felt, distorting all my encounters with people and the world. (But of course, under capitalism, there is no social interaction that isn't distorted by class position, no neutral social field that exists beyond social antagonism). I suppose I had my first conscious tastes of inferiority when, in the school holidays, I went with my mother, who worked as a cleaner, to the houses of the well-to-do. Feeling lesser simply wasn't an issue; it was experienced as a non-contestable fact. At least now - and this is partly thanks to CBT - I am aware both of the way in which that the sense of ontological inferiority colours my experience - sometimes I can practically sense it as an entity, a grey vampire squatting on my shoulders, heavy and draining; and I have learned to reduce its power, if not to eliminate it. One of the other tensions that constantly came up with my therapist was over the cause of this feeling of inferiority: for me, it was clearly a class issue, and I dream of a Marxist therapy that could address the pyschic wounds of class society.

Mentioning a working class background may seem glamorous or cool to some, but what we are talking about here are the very non-glamorous feelings of shame, embarrassment and inadequacy. Tone of voice is sufficient to trigger that feeling of inadequacy: that is partly the reason that the sepulchural tones of Radio 4 drive me into a rage, the plummy, affectless voices sending the implicit message that any excitation is some juvenile deviation from commonsense mundanity. (Owen is just developing a concept of 'mundanism', which does seem absolutely central to Popism and other variants of deflationary hedonic relativism. Notice the way commonsense mundanism is integral to ruling class anti-intellectualism - see for instance Pseud's Corner and ILM - with Oxbridge graduates pretending to be plain, common men who just don't understand Theory but who know, by george, that it's damn silly.)

Raise the issue of class to many ex-Public School types and they will be flustered and offended, as if making them aware of their class position were some unpardonable impertinence. But I'm afraid that the rest of us are made aware of our class position almost constantly. At the same time, I believe that a measure of sympathy towards their plight is warranted. The maiming is so savage that Mark E Smith was surely at his most sage when he said that going to Public School was 'punishment enough'. A privileged background is usually an existential malediction, a psychic blight - expectations are raised so high that even becoming Master of the Universe would seem a failure, which is why so many Oxbridge graduates and Public School types have a cheated, world weary look on their faces. (Whereas, it was easy for me to feel that I had achieved something, because no-one in my family had got an A-level, never mind a degree.) If there is nothing more boring than a ruling class person in torment about their position and privilege, if there is nothing sadder than a Public Schoolboy pretending that eating spaghetti hoops is a revolutionary act, it is still possible for share the benefits of their learning with others: a redemption of sorts.

_________________________________________________________________

The very interesting discussions that followed my talk at Tent State focused most insistently on the issue of the family (and alternative kinship structures), questions to which I shall return in the two long-promised Edelman/ Queer Theory posts.