June 09, 2007

No promises, but...

What is it about promising to write posts that guarantees that they won't be finished, or will be finished only after a tortuously extended period?

Is it simply that when something has been promised it becomes something one ought to do instead of something one wants to do? Many of my posts - including some of what turned out to be the most important ones - arose semi-spontaneously, when I had perhaps only intended to put up a link with only a few words of comment. In common with all modes of jouissance, the jouissance of blogging often arises by accident, by the avoidance of an official goal, the thought that 'this isn't what I should be writing about now, but I'll just write a bit more...'

In any case, my plan to have posts up early this week was derailed. Partly by a fabulous few days in London last weekend, so inspiring that they produced a whole set of other virtual posts that seemed more urgent than those I had previously intended to complete, partly because of deadlines and visitors this week. So in a bid to catch up, and to quickly sketch in a few ideas before they are forgotten, I offer the following ragbag set of reflections, which are connected only by the fact that they occurred to me in the period since the last post.

Two interesting interviews with Simon, one at Ballardian, the other, by Bat, at Socialist Worker. (Speaking of Bat, he has a fascinating take on Rihanna's 'Umbrella', which I hope he will post soon - incidentally, at this stage, it's looking very possible that Rihanna may well end up producing my favourite singles of both 2006 and 3007.) There's a great deal of bad resentment about Simon doing the rounds, but I like to think that his success is due, not only to his talent, but also to his grace, reliability and willingness to encourage others. Nice guys don’t always finish last…

’Permission to give Latimer a beating, sir’. A really rather good Dr Who two-parter, by Paul Cornell, concluded on Saturday. The story was adapted from Cornell’s own New Adventure novel. (Throwing up an interesting philosophical quandary…. The New Adventure novels were written in the period after the show had originally been cancelled in 1989 and at the time they constituted what appeared to be the only official continuation the series would have. But now that the Human Nature novel has been adapted, it seems to have been retrospectively demoted to a lower ontological status in the programme’s ‘reality’. Cue all sorts of debates in fandom about whether the novel is ‘canon’ - this usage, rather than the grammatically standard ‘canonical’, is preferred by Dr Who fans – , whether there is a Doctor Who canon of texts which officially belong to the programme’s reality at all – because, unlike with Star Wars and Star Trek there is no official authority which ‘rules’ on which texts do or not count in the official reality – and whether enjoyment can be retrospectively stolen.)

The plot of the two episodes concerned the Doctor transforming himself into a human being - a schoolteacher in a 1913 school, called John Smith - so as to evade a predatory family of aliens. It can't only be me who was crushingly disappointed at the moment when the restrained John Smith gave way to the gurning, overexcited postmodern Kenneth Williams that is David Tennant’s tenth Doctor. If there is a personification of the new BBC, it would be Tennant’s Doctor – at one and the same time, neurotically ingratiating in his desire to please and oh-so-pleased-with-himself smug.

In effect, the conceit allowed Dr Who to temporarily de-Buffyize itself, to dispense with so many of the features that we are told are essential to its continued success, to shuck off all the tiresome popcult references, the hormonally-crazed emotional porn (the love relationship between Smith and the matron was all the more powerful for its restraint), the hectic pace (it was notable that far more seemed to happen in these two episodes than in any two episodes paced at breakneck speed). In becoming a 1913 human, the Doctor became far more alien to 21C culture than he has ever seemed in his tenth incarnation.

Oestrogen-deficiency. Me on Soul Jazz’s Box of Dub…

Bigmouth strikes again...and I've got no right to take my place/ in the human race... Owen is the first off the blocks to express dissatisfaction with the No Future Together event (although Dominic, who didn't attend the conference, inadvertently - but with impeccable, perhaps uncanny, timing - highlighted many of the problems that the symposium gave rise to in this superb post on kinship). The conference was highly stimulating, albeit, for the most part, negatively so, provoking me into a long delayed engagement with Queer theory. (I won't promise to post any more of that engagement here, for fear of giving rise to the hex I described above.) Owen has already highlighted the principal problem as I saw it: the failure to derive from Edelman's critique of 'reproductive futurism' a collective alternative to the Right's 'family values'. The conference - including Edelman's keynote presentation - seemed to evade all of No Future's traumatic implications for theory. Is the problem the appeal to the future per se, and what would it be like to have a type of theory that was no longer anchored to any concept of the future at all? Or is it only 'reproductive futurism' that it is the problem, and, if so, what would a non-reproductive futurism look like? Raising these questions - which I did in perfectly good faith - was, shall we say, not welcomed.

Edelman's presentation of bareback gay male porn as some anti-heroic anti-Christian humbling of a Man already as dead as God was disappointing, to say the least. With his paper, and with the paper by the Chair in Aberrant French Sexualities' (not her real title, but only a slight caricature) we were in an all-too familiar transgressive space that, as Joel Anderson pointed out, Lacan was the very theorist to most effectively critique. The elementary Lacanian question 'for whom are you doing or talking about X?' was evaded. Who is that is scandalised or appalled by references to sexual practices that risk death, and why should scandalising them be the implicit aim? If the goal is not, or no longer, to petition the State for rights, surely there has to be more at stake than a perverser-than-thou desire to demonstrate to a big Other whose existence is at the same time disavowed how naughty one can be? (Daddy, you can’t make me protect myself, it’s my body and I’ll die if I want to…)

Owen is right: the point at which the Queer was paralleled with the child was both deeply unfortunate and revelatory. Again, it is an elementary lesson of Lacanianism that polymorphous perversity cannot be recovered, nor is it present in the human child in any unmediated way. The very moment a baby is born, it screams: i.e. it makes a demand to the Other. All of its activities - especially the most supposedly 'natural' ones - are very quickly tied up in signification. This is not simply to do with the role of language, but the play of approval and disapproval, so that shitting and eating are immediately and inextricably connected to with what pleases or displeases mummy and daddy. To shit is never only a natural process, but also a sign. So being seen to deliberately put one's life at risk, or being seen to smear one's face in the excrement of transgression, can never be simply a matter of devil-may-care abandon. And this dimension of 'being seen to do X' cannot be avoided, especially if you are very pointedly being seen to talk about supposedly unspeakable practices in a university. The pretext of transgressive panto-mummery - if only the fusty old Symbolic weren't there, the pervert could be, like, free to do what he wants, - barely conceals its disavowed reliance on a disapproving gaze. And the tragic impasse for discourses of transgression is that an act doesn't cease to be mummery no matter how extreme, how 'authentic' it is. Even death remains a sign.

The big Other cannot be transgressed away, and the conference also highlighted something that has really begun to grate on me: the incessant appeal in contemporary culture to the 'radical'. When every New Labour neo-liberal 'reform', when every theory in the Humanities, no matter how insipid, has to be touted as 'radical', shouldn't alarm bells be ringing about the impulse to claim radicalism? It's possible, of course, to argue that these ostensible forms of radicalism are not authentic, that there is a real radicalism that all these fake candidates never attain. But why not pursue the opposite route, and stake out a new orthodoxy, a big Other that is not disavowed but acknowledged? (Couldn't one role of concepts of faith and fidelity be to displace the exhausted language of 'subversion'?) (None of the above questions are rhetorical by the way.) The paradox of course is that the big Other's non-existence can only be confronted when the big Other is acknowledged; when it is ignored or overlooked, it insists all the more powerfully.

The child's face is the ultimate ethical trap. Some of the most interesting discussions at the No Future event concerned the Madeleine Mccann phenomenon. Mandy Merck - for me the best speaker at the conference - was excellent on this. I'll try not to repeat points that have already been well made by Antigram, but the coincidence of the 'Maddy' hysteria with the No Future event was highly suggestive. What better example could there be of Edelman's claim that the figure of the child is an unrefusable moral blackmail in contemporary culture? I need hardly say, I hope, that of course the disappearance of Madeleine Mccan is a horrific event; but we are not dealing only with the fate of a little girl any more. The media injunctions about Madeleine Mccan have the apparent form of ethical demands - we should maintain awareness, we should feel compassion - but they have no ethical content at all. Rather, the demand that 'awareness' be raised is a symptom of the persistence in postmodernity of the supposedly primitive belief structure of magical thinking (the idea that thoughts can have a direct effect on reality); and the useless, narcissistic compassion we are invited to feel for the Mccans - how will that help, them or anyone else? - is the piety that is the flipside of media cynicism. It's not only that Madeleine Mccan's face is used to cover up other geopolitical events, as Antigram shows; it is also that the pseudo-ethics surrounding one child's face are used to blind us to systemic injustices that lead to the suffering and deaths of many thousands of children and adults every day. (And the sight of the Pope - who actually could do something concrete about systemic child abuse in the Roman Catholic Church if he wasn't dragging his feet - piously engaging in a thought transference ritual with the Mccan's is really too grotesque to contemplate.)

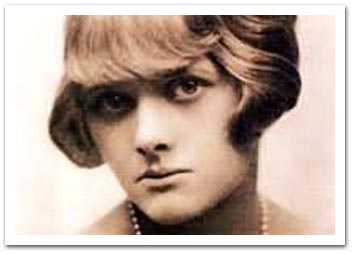

The divine Daphne.

Edelman’s andro-(ab)normativism – in principle it is not only the male homosexual who can occupy the position of the Queer, but in fact most of Edelman’s examples end up being gay men (Antigone and the Birds are, as far as I recall, the only two cases of Sinthommosexuals in No Future who aren’t men) led me to thinking about du Maurier. As yet, I confess to have only encountered du Maurier indirectly, through the film adaptations of her work. But what films … The Birds, Don’t Look Now and Rebecca. (And what, by the way, of Hitchcock’s relationship to Queer women, since he adapted three of Du Maurier fictions, and one of Highsmith’s?) Rebecca, a film that haunts and is haunted – perhaps most of all by Jane Eyre, its ancestor-doppelganger. Rebecca, which like Jane Eyre and many of Highsmith’s novels achieves uncanny – or would it be better to say queer - effects without any recourse to the supernatural. (A question I want to raise but can’t answer yet: what is the relationship of the Queer to the Uncanny and the Weird?) Rebecca, which can only be placed in the interstices of genre: Du Maurier denied it was a romance, but what else is it? This un-romance which, unlike the classic romance novel, begins not ends with marriage – first there is the sham marriage, Symbolically mandated but existentially and affectively a charade, then there is the true marriage, with the couple destituted, dispossessed of the Symbolic property, Manderley. (A near reversal, or better, a skewing, of Jane Eyre, in which Jane and Rochester, governess and master, first of all live as if husband and wife, without Symbolic mandate and without sex, and can only be officially married only after Thornfield has burned down. In the case of Jane Eyre, the Other woman has to be killed before the marriage can occur; in the case of Rebecca, the Other woman – Rebecca herself – blights the marriage by already being dead.) But isn’t Rebecca a sinthommosexual, as a brilliant piece on du Maurier in the Independent last month, suggested?

- [F]ar from being a demure wife, it turns out, Rebecca was a sexually free spirit who held the bonds of marriage in contempt. We aren't told what she got up to: Max de Winter won't give it a name. But "she was not even normal", he says, savagely. "I don't want to tell you about [those years], the lie we lived, she and I." If he is repulsed, however, Danvers is admiring. Rebecca's close companion and maid for many years, "Danny" is clearly still in love with her. Rebecca "had all the courage and spirit of a boy", Danvers says. "She ought to have been a boy." Rebecca's affairs with men meant nothing, Danvers insists: "She despised all men.... Lovemaking was a game to her, only a game. She did it because it made her laugh. I've known her come back and sit upstairs in her bed and rock with laughter at the lot of you."

- What has happened to Rebecca, this vital, forceful creature who we are told had the face of a beautiful boy, who went through life shaking with silent laughter, thumbing her nose at the world? Before the novel even starts, she has been killed, locked in a box forever - the tiny cabin of her boat - and buried beneath the sea. Du Maurier may have raved "to hell with psychoanalysis", but that's as clear an image of repression as you can get. It fails, as repression fails: the attempt to blot out Rebecca has only made her stronger. Though dead, she still dominates the book. She is the centre around which the thoughts of the others constantly revolve. Even the boat her body lies in is called Je Reviens ("I will return"). Her presence haunts Manderley, where it is felt in every room: the second wife sees her possessions, her taste, as "vividly alive, having something of the glow of the rhododendrons... rich and glowing in the morning sun".

The second wife's growing obsession with Rebecca, which du Maurier claimed was jealousy, begins to seem curiously like desire as the book proceeds. For one, there's a preoccupation with Rebecca's physical attributes, which she cannot seem to control. "Wherever I walked in Manderley, wherever I sat, even in my thoughts and in my dreams, I met Rebecca," she says. "I knew her figure now, the long slim legs, the small and narrow feet. Her shoulders, broader than mine, the strong and clever hands... If I heard it, even among a thousand others, I should recognise her voice. Rebecca, always Rebecca." In a telling episode, she goes on the sly to inspect what had been Rebecca's bedroom, "my heart beating in a queer excited way". Once there, she begins to fondle Rebecca's intimate possessions. She notes that the room smelt "queer" - that word again. At that moment the door opens and in comes Danvers, "triumphant, gloating, excited in a strange unhealthy way". Danvers comes nearer. "Now you are here let me show you everything," she says. "'I know you want to see it all, you've wanted to for a long time, and you were too shy to ask.' She took hold of my arm, and walked me towards the bed. I could not resist her." But Danvers doesn't thrust the wife on to the bed and have her evil way with her, as you might expect. Instead, she talks obsessively about Rebecca. "I did everything for her, you know..." The mood darkens as Danvers describes the night of Rebecca's death, then becomes intimate again: "When Mr De Winter is away, and you feel lonely, you might like to come to these rooms and sit here ... I feel her everywhere. You do too, don't you?"

Though this scene pulses with the narrator's "queer" excitement, there's dread, too, and distaste: far be it from du Maurier to admit to "that unattractive word that begins with L". Danvers, in other words, is a threatening character because she represents what du Maurier thought of as a threatening thing. She, like Rebecca, is "a menace". She is often described as looking dead, a "black figure" with a "skull's face" and "hollow eyes". That is partly because she is, in one sense, a dead woman: her heart is in the grave with Rebecca. Like the second wife, who feels herself to be a ghost, and Rebecca herself, Danvers is a "disembodied spirit", "all wrong".

With all this, it's perhaps surprising that heterosexuality wins in the end. Or does it? After all, Max de Winter and his bride are forced into exile in a foreign land, where they fritter away their time in dull routines, talking about cricket. They lose Manderley, which stands for many things, among them class, privilege, marriage, domesticity, all destroyed, burned to the ground by an enraged lesbian (who gets away scot-free, too, in contrast to the film). In fact, Manderley can be seen as another box: a grandiose box, but a box nonetheless, in which the second wife feels herself to be buried.

We’re apt to read Du Maurier’s distaste for the ‘L word’ as a symptom of the repression of her historical period – just as we are likely to attribute the avoidance of the settling of the question of Ripley’s sexuality in The Talented Mr Ripley as merely an effect of Highsmith not being able to say, in the 1950s, what he ‘really’ was. But it’s equally possible that the refusal to be defined by one (sexual) predicate is what makes Du Maurier and Ripley queer rather than simply gay. Highsmith’s genius in having Ripley married at the start of the second novel, Ripley Under Ground - he and his wife Heloise remains happily married, that is, in a state of contented non-relation, throughout all the subsequent novels - does not definitively settle the question of his sexuality, it keeps it open. And if Ripley cannot be defined by one predicate, neither can his queerness. What makes him queer is some indefinable X that cannot be ‘located’ in any one of his determinate properties…

Posted by mark at June 9, 2007 02:41 AM | TrackBack