August 27, 2006

Let me be your fantasy

k-punk's contribution to the inter-weblog pornography symposium, attended (so far) by Infinite Thought, Bacteriagrl, Measures Taken, Different Maps and Poetix

What Ballard, Lacan and Burroughs have in common is the perception that human sexuality is essentially pornographic.

For all three, human sexuality is irreducible to biological excitation; strip away the hallucinatory and the fantasmatic, and sexuality disappears with it. As Renata Salecl argues in (Per)Versions of Love and Hate, it is easier for an animal to enter the Symbolic Order than it is for a human to unlearn the Symbolic and attain animality, an observation confirmed by the news that, when an orang-utan was presented with pornography, it ceased to show any sexual interest in its fellow apes and spent all day masturbating. The orang-utan had been inducted into human sexuality by the 'inhuman partner', the fantasmatic supplement, upon which all human sexuality depends.

The question is not, then, whether pornography, but which pornography?

For Burroughs, pornosexuality would always be a miserable repetition, a Boschian negative carnival in which the rusting fairground wheel of desire forever turns in desolate circles. But in Ballard, and in Cronenberg's version of Ballard's Crash, it is possible to uncover a version of pornography that is positive, even utopian.

Cronenberg's work can be seen as a repsonse to the challenge Baudrillard posed in Seduction. Hardcore pornography haunts late capitalism, functioning as the cipher of a supposedly demystified, disillusioned 'reality'. 'A pornographic culture par excellence: one that pursues the workings of the real at all times and all places.' Here, hardcore is the reality of sex, and sex is the reality of everything else. Hardcore trades on a kind of earnest literalism, a belief that there is some empirically specifiable 'it' which = sex in/as the real. As Baudrillard wryly noted, this empiricist bio-logic is fixated on a kind of technical fidelity - the pornographic film must be faithful to the (supposed) unadorned, brute mechanism of sex. Yet, sign and ritual are inescapable: in hardcore, especially in bukkake, the function of semen is, after all, essentially semiotic. No sex without signs. The higher the resolution of the image, the closer you get to the organs, the more that the 'it' disappears from view. There is no better image of this 'orgy of realism' than the 'Japanese vaginal cyclorama' Baudrillard described in the 'Stereo-porno' section of Seduction. 'Prostitutes, their thighs open, sitting on the edge of a platform, Japanese workers in their shirt-sleeves ... permitted to shove their noses up to their eyeballs within the woman's vagina in order to see, to see better - but what?' 'Why stop with genitalia?' Baudrillard asks. 'Who knows what profound pleasure is to be found in the visual dismemberment of mucous membranes and smooth muscles?'

Cronenberg's early work - from Shivers and Rabid through to Videodrome - is an answer to that very question. Cronenberg famously posed his own question, 'why aren't their beauty contests for the inside of the body?', and Shivers and Rabid posit an equivalence between body horror and eroticism. The ostensible catastrophe with which both films conclude - the total degeneration of social structure into a seething, anorganic orgy - functions ambivalently. The disintegration of organismic integrity, the reversion to the condition of the pre-multicellular, is a kind of parodic-utopian riposte to Freud's Civilzation and its Discontents. If civilization and unbound libido are incommensurate, it is implied, so much the worse for civilization. The appartment block taken over by mindless sex zombies at the end of Shivers is the Sixties dream of liberated sex come true...

Crash is a sober retreat from all this, a model for a new mechoMascohistic mode of pornography in which it is no longer the so-called inside of the body that matters, but the body as surface - a surface to be adorned with clothes, marked by scars, punctured by technical machinery. Possessed by a mad passion to exchange biotic code, the sex plague victims in Shivers devolve beyond animality into a kind of bacterial replicator frenzy. By firm contrast, Crash is as passionless as a Delvaux dream. Sex here is entirely colonized by culture and language. All the sex scenes are meticulously constructed tableaux, irreducibly fantasmatic, not because they are 'unreal', but because their staging and their consistency depend on fantasy. The film's opening scene, with Catherine Ballard in the aircraft hangar, is quite clearly an acting out of a fantasmatic scenario; it also functions, later, via its recounting, as a fantasmatic supplement to the first sexual encounter we see between Catherine and James. There is no 'it' of sex, no brute, naked, definable moment when 'it' happens, only a plateau that is (paradoxically) both dilated and deferred, in which words and memories reverberate more powerfully than any penetration.

Crash is so indebted to Helmut Newton that it often looks like little more than a series of animated Newton images. Or, better: in Crash, the bodies attain the near-inanimate stillness of Newton's living mannequins. The echoes of Newton are entirely fittingly, since Ballard regarded Newton as 'our greatest visual artist', a Surrealist image-maker whose vision shamed the mediocrity of those officially working in the fine arts. 'In Newton's work,' Ballard writes, 'we see a new race of urban beings, living on a new human frontier, where all passion is spent and all ambition long satisfied, where the deepest emotions seem to be relocating themselves, moving into a terrain more mysterious than Marienbad.'

When Cronenberg talks about the future sexuality of the 'new race of urban beings' in Crash, he tends to refer to it negative terms. 'The conceit that underlies some of what is maybe difficult or baffling about Crash, the sci-finess of it, comes from Ballard anticipating a future pathological psychology. It's developing now, but he anticipates it and brings it back to the past - now - and he applies it as though it exists completely formed.' The Ballards' marriage is to be understood as inherently dysfunctional:

- Some potential distributors said, 'You should make them more normal at the beginning so that we can see where they go wrong.' In other words, it should be like a Fatal Attraction thing. Blissful couple, maybe a dog and a rabbit, maybe a kid. And then a car accident introduces them to these horrible people and they go wrong. I said, 'That isn't right, because there's something horribly wrong with them right now. That's why they're vulnerable to going even further.'

Yet the Ballards 'pathology' in Crash seems oddly healthy, their marriage a model of well-adjusted perversity. Theirs is a utopian sexuality, where sexual contact is voided of all sentimentality, stripped of any reference to reproduction, and unfreighted by any guilt. The lack of face-to-face sex in the Ballards' marriage - which, again Cronenberg himself tends to talk of negatively, as if it were a deviation from some wholesome, facialized sex in which the partners achieve a harmonious oneness - points to an awareness that there is no sexual relationship. Yet, very far from being a difficulty for the Ballards' marriage, the lack of a direct rapport, the recognition that any sexual encounter has to go via fantasy, is the basis of all their erotic adventures. Compare the Ballards' marriage to that of the Harfords in Eyes Wide Shut. The Ballards' using of their sexual encounters with others as a stimulus for their own - impassive, poised, oneiric - sex forms a clear contrast with the deadlock of the Harfords' marriage, which is exposed in Bill's failure to cope, or keep up, with Alice's fantasy. While Bill is scandalized by Alice's articulation of her fantasies, sex in the Ballards' marriage is governed by the 'feminine' drive to talk; it is almost as if all of the physical encounters happen only so that they can be converted into stories to be recounted later.

The most charged scene in Crash takes place in the carwash, where James looks on through the rearview mirror at Catherine and Vaughan, who - in the words of Cronenberg's script - are 'like two semi-metallic human beings of the future making love in a chromium bower'. Deborah Unger, the film's real star, is particularly impressive here. A kind of feline automaton, she 'acts with her hair, minor adjustments, tosses of the head that advertise the transit of small emotions.' (Iain Sinclair)

Who is using whom here? The answer is that all three of the characters are using each other. Catherine's encounter with Vaughan stimulates James, just as Catherine is stimulated by the thought that James is watching her with Vaughan. Vaughan is using the couple as subjects of his own libidinal experiments, while the Ballards are using Vaughan as the third figure in their marriage. A mis-en-abyme of desire...

Far from being some nightmare of mutual domination, this is Cronenberg/ Ballard's sexual utopia, a perverse counterpart to Kant's kingdom of ends. The kingdom of ends was Kant's ideal ethical community, in which everyone is treated as an end in themselves. Kant reasoned that, from the point of view of his ethics, sex was inherently problematic, because to engage in sexual congress entails treating the other as an object to be used. The only way in which sex could be commensurated with the categorical imperative - which in one of its versions maintains that one should never treat others as a means to an end - was if it took place in the context of a marriage, in which each partner has contracted out the use of their organs in exchange for the use of their partner's.

Desire is construed here in terms of simple appropriation (this equivalence is yet another way in which Kant is in tune with Sade). But what Kant - and those who follow him in condemning pornography because it 'objectifies' - fails to recognize is that our deepest desire is not to possess an other but to be objectified by them, to be used by them in/ as their fantasy. This is one sense of the famous Lacanian formula that 'desire is the desire of the other'. The perfect erotic situation would involve neither a dominance of, nor a fusion with, the other; it would consist rather in being objectified by someone you also want to objectify.

Crash, of course, follows Masoch and Newton in delocalizing sex from genitality. Libido is invested in the mis-en-scene more than in the meat, which draws its attraction almost entirely from its adjacency to the decorous nonorganic - to clothes as much as cars. Clothes differentiate Glam's cold and cruel cultivation of appearances from hardcore's passion for the real. Without suits, dresses and shoes, without fur, leather and nylon, pornography might as well be arranging meat in a butcher's window. Newton told Ballard that he 'loved Cronenberg's Crash, but one thing bothered him. 'The dresses,' he whispered. 'They were so awful.'' This strikes me as waspishly unfair to Denice Cronenberg's elegant wardrobe selections. (One major problem with Jonathan Weiss' version of The Atrocity Exhibition, however, is precisely the dreadfulness of the clothes.) Crash takes its cues from high fashion magazines, whose images are more sumptuously arty than fine art, more suffused with deviant eroticism than hardcore porn. Would be impossible for there to be a pornography, sponsored by Dior or Chanel, scripted by a latter-day Masoch or Ballard, whose fantasies were as artfully staged as the most glamorous fashion photo shoot?

Thanks to Infinite Thought for DVD scans

August 24, 2006

A desire to sunbathe, moan and die

I like this, from Brian Reade, in the Mirror today:

- A QUARTER of a million Poles now work in Britain, leading some experts to claim they're bringing untold misery to our shores.

It could be worse. Think about it. They're mostly young, English-speaking, non-benefit claiming grafters, grateful to do jobs we won't, happy to integrate and be net contributors to the tax system.

Now look at Spain, with the quarter of a million Britons who have fled there.

They're mostly old, non-Spanish speakers, who use their EU citizen status to burden their health system, and whose idea of integration is chipping in with the other British ex-pats in their apartment block to pay a pittance to a Spanish security guard to keep the natives out.

The Poles come here with optimism, a desire to work and build a new life. Brits go there filled with bitterness and a desire to sunbathe, moan and die.

This, about the shameful racist delirium and vigilante 'profiling' in Malaga, is also mordantly apt --- 'political incorrectness gone mad' indeed...

Slow Propulsion

My interview with Jeremy from the Junior Boys is now up on the Fact website.

- The principal influence on the new record is disco, and I think that had a tremendous effect on the 'rhythm of the record'. Disco, we came to realize, occupies a strange rhythmic place, because while itís very steady, itís also rather slow. Itís usually about 110 to 120 BPM, much slower than modern house/techno music. So we thought it would be really interesting to set our music in this kind of space. So a lot of the record has that strange slow propulsion to it.

All the sidestepped cars...

Showbizwhines, minute detail

It's a hand on the shoulder in Leicester Square

I am moving out of London this weekend - finally exiting this Roman Shell - so bear with me for a while.

Time is very short over the next few days, but I'll do my best to have my contribution to the porn symposium (already featuring Infinite Thought, Different Maps, Measures Taken, Bacteria Grl and Poetix) up at the weekend.

Incidentally, I know there are some people who are worried that the second part of my Fall post will never appear. Don't worry: it is already several thousand words long, but it does need a little more work...

August 17, 2006

I'm lost, you got me looking for the rest of me...

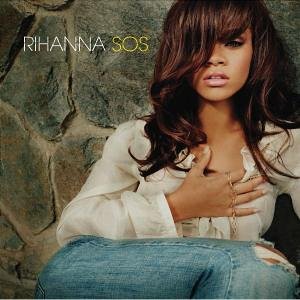

I almost missed one of this year's great songs about obsession, Rihanna's 'SOS'. It nearly passed me by because my initial encounters with the song came via the video. The punitive predictability of R and B* promos (interchangeable digitally-slicked flesh endlessly rolling off an editing suite production line) repels interest, so I paid little heed to 'SOS' - 'Tainted Love' sample notwithstanding - when it came out a few months ago.

My interest in 'SOS' was piqued by Rihanna's follow-up single, the fabulously overblown ballad, 'Unfaithful'. 'Unfaithful' is a ballad in a quaint and apparently outmoded sense, in that it is about regret, pain and responsibility rather than getting it on. But listening back to 'SOS', you realise that it, too, is not so much about carnality as the pathology of love.

'SOS' ingests the sonic substance of the Soft Cell version of 'Tainted Love' - the familiar coldly addictive electronic bass line and subway-at-night synth stabs - but remotivates it. (Interesting to note that 'SOS' returns 'Tainted Love' to a black woman, the song having passed from Gloria Jones to Soft Cell - I'm ignoring Marilyn Manson, obviously.) The toxicity in 'Tainted Love' came from betrayal and infidelity, love turning sour; with 'SOS' love itself is inherently poisonous: 'it's not healthy... for me to feel this way... it don't feel right'. If there is betrayal in 'SOS', it is (implicitly) Rihanna who is doing the betraying (the 'don't feel right' suggesting moral corruption as well as love's dis-ease).

'Tainted Love' was about the struggle between the desire to remain intoxicated by love's sweet sickness and the wish to throw the monkey off the back. There was more than a hint that the grandstanding, climactic declaration - 'now I'm going to pack my things and go' - was bravado, a statement made without meaning it, or made only in front of the mirror. The very form of the song, the very fact that the wronged lover is still addressing the betrayer, indicates that the fixation remains. The threat of leaving is still a demand addressed to the lover who is supposedly being rejected. The truth of 'Tainted Love' is no doubt contained in the line 'I love you though you hurt me so' except that the line should read, 'I love you because you hurt me so....'

The form of the love song is often that of a letter which is not sent, or should not be sent. (The psychosis of David Kelsey in Highsmith's This Sweet Sickness is that he has no concept that could be such a thing as a letter that should not be sent, a feeling that should not be symbolically transmitted.) The most powerful love songs always turn on the discrepancy between the act of declaring love and the knowledge that the ostensible addressee is no longer there, was never there, and could never be there. Everyone knows that people continue to write letters or to talk to lovers long after the loved one is dead. But, very far from being unusual, this is the reality of erotic love laid bare. To give up the fantasy that there is someone there listening is far harder than giving up the object itself. The converse of this is the horror of receiving love letters or declarations of love: we know is that they are never really addressed to us.

'SOS' retains the theme of obsession, but, unlike 'Tainted Love', 'SOS' is about the head-over-heels, early stages of love. The willing submission to love's vertiginous sickness is an encounter with the hole at the heart of subjectivity : 'I'm lost/ you got me lookin' for the rest of me'. The contest between love and the subject is always unequal: 'Love is testing me but still I'm losing it'. Check the way in which Rihanna gives sibilant voice to a phrase like 'stressing, incessantly pressing', and the leering way she delivers the line (a steal from the 'Tainted Love' lyrics, of course) 'toss and turn/ can't sleep at night'. It as if she is the voice of the maternal superego, which knows that its demands to 'enjoy' can never be met, and which gains its own enjoyment from witnessing our torment. (Perhaps it is oddly fitting, then, that 'SOS' should have been used by Nike: lovesickness as an analogue for 'the sheer explosive pointlessness of capital itself'?)

Releasing 'Unfaithful' as the next single make it seem like the next instalment in a story. It's a few months later; the dizzying allure of the affair has dissipated, and Rihanna is overcome by guilt. Both she and the lover she has betrayed know she has being having an affair, although this knowledge remains unspoken: 'And I know that he knows I'm unfaithful/ And it kills him inside..' (I pause to note that 'Unfaithful' is just about the only record by a contemporary black female to be have made the Radio 2 playlist in the last few months - there's plenty of Razorlight and Snow Patrol, naturally.)

'Unfaithful' is remarkable for its gloriously unselfconscious, baroque sense of drama - like a muted Jim Steinman production, if you can imagine such a thing. 'I don't wanna do this any more/ I don't wanna take away his life/ I don't want to be.... a murderer....' It is remarkable also because it has a woman assuming the role of betrayer. If 'SOS' was about the jouissance of losing one's autonomy, 'Unfaithful' is about belatedly taking responsibility. 'On a lot of records,' Rihanna says, 'men talk about cheating as though it's all a game. For me, "Unfaithful" is not just about stepping out on your man, but the pain that it causes both parties.'

'SOS' was turned down by Christina Milian, and Rihanna now emerges as the most serious rival to both Milian and Beyonce. (She shares their notorious work ethic: her latest album, A Girl Like Me is Rihanna's second in less than a year.) Rihanna, a mere 18, wants to position herself as 'having a personal conversation with girls my age. My goal on A Girl Like Me was to find songs that express the many things young women want to say, but might not know how.' Certainly, there is a space for female desires and anxieties on Rihanna's record that is missing on Milian or Beyonce's recent records. The persona Milian projects in her songs - witness her absolute mistresspiece, 'I Can Be That Woman' - is passive to the point of abjection. Beyonce, meanwhile, has moved from singing clever songs about ambivalence and the failings of men to subordinating herself utterly to a caricatured male desire. She is now either the devoted Soul sister cooing bland syrup (a la most of the last Destiny's Child album) or the pneumatic sex machine who will do anything for her man.

The significance of the subjective position adopts in 'Unfaithful' is that it is about both female desire and responsibility. Even the preposterous self-assertion of something like Destiny Child's 'Survivor' stilll assumed a woman that, although undefeated, was wounded by a man, and who still addressed her statement of triumph to the man who had underestimated or dismissed her. 'Unfaithful' is peculiarly touching because it is not addressed to a man at all; it is written in the third person, as if Rihanna is talking to a friend about what she has done. The real addressee of 'Unfaitfhful', of course is the big Other. Perhaps it is only in the third person, when the fantasm of reciprocity is set aside, that expressions of love can pass beyond narcissism.

* Strictly speaking, it is perhaps a little misleading to describe Rihanna's sound as R and B. Even though Jay-Z is executive producer on A Girl Like Me, the album is thankfully free of the rap cameos that blight most R and B. Indeed, A Girl Like Me, which has - to my ears - at least eight possible hits on it, holds open the utopian possibility of a black music liberated from the dead phallic weight of hip hop. A Girl Like Me's mixture of electro, dancehall, old skool skank and R and B makes it something like a Cupid & Psyche 2006. It isn't the sadness of some of the songs that makes the album unique; it is their ambivalence. Check the next single, 'We Ride', for instance, a superficially summer-breezy tune that turns out to be freighted with conflicted longings.

August 15, 2006

'Fashion's Great Sphinx'

|  |

- The masses have been "seduced" in the modern era by only two great events: the white light of the stars and the black light of terrorism. These two phenomena have much in common. Terrorist acts, like the stars, "flicker:" they do not enlighten, they do not radiate a continuous, white light, but an intermittent, cold light; they disappoint even as they exalt; they fascinate by the suddenness of their appearance and the imminence of their disappearance. And they are constantly being eclipsed as they each try to outdo each other.

The great stars or seductresses never dazzle because of their talent or intelligence but because of their absence. They are dazzling in their nullity, and in their coldness - the coldness of makeup and ritual hieraticism (rituals are cool, according to McLuhan).

- Baurillard, Seduction

We still have the terrorism, but we no longer have the seduction of the Star. Or such seduction is rarer, far rarer, than it was in 1977.

'The death of the stars is merely punishment for their ritualized idolatory,' Baudrillard went on. 'They must die, they must already be dead - so that they can be perfect and superficial, with or without makeup.' At this time, Baudrillard could still imagine a death that 'itself shines through its very absence, ... turned into a brilliant and superficial appearance'. This was still the age of cinema, and Seduction would turn out to be its epitaph. Neither cinema, nor seduction, nor the Star, would survive the period of TVerite celebreality Baudrillard was already anatomizing. A different death awaited, no longer a death that was brilliant and superficial, but the death represented by banal psychological depth.

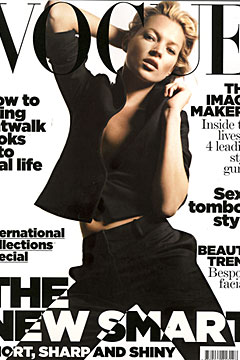

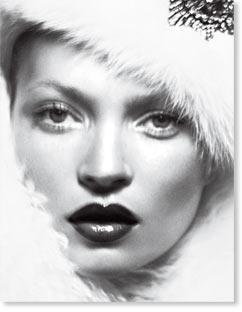

A year ago, the tabloids, with their customary solemn hysteria, passed a death sentence on Moss's career --- but here she is, in August 2006, on the front of both Vogue and Vanity Fair. In fact, Vogue informs us that, in addition to being its cover-star for a record-breaking 23rd time, Moss features in no less than eight adverts this month: 'Dior on page 11, Louis Vuitton on page 15, Versace on page 49, Burberry on page 50, Stella McCartney on pages 86 and 87, Longchamp on page 139, Belstaff on page 240 and 241 and Rimmel on page 389.'

A A Gill's excellent puff-piece on Moss in Vanity Fair - accompanying some wonderful photographs which have Moss sumptuously re-staging the Silent era Star poses of Garbo, Dietrich and Harlow - stresses that it is Moss's notorious refusal to speak that guaranteed her sublimity remained unassailable. Moss's career as Image would indeed have died if she had taken the tabloid bait and entered its Confessional. To respond to the demand to speak, to have herself assumed the banalizing soap opera role of 'troubled star' which the tabloids had scripted for her, would have won her the temporary sympathy of the populist big Other, but would have permanently cost her the aristocratic cache which keeps the high fashion contracts coming in. The tabloids have always resented Moss because she has never been their Thing; she passes through their pages, immaculately immune to all their anti-Glam techniques (Gill: 'However hard they tried - and they tried - she's incapable of taking a grim, morning-after, baggy, saggy, up-the-nose shot'). Gill again:

- Moss's zipped-lipped lack of cant and hypocrisy implies that she won't be held responsible for society's worries about drugs or anorexia or family values, or its fears for its children. She's a fashion model, not a role model. You want to be like Kate Moss? Be yourself. All there is of Kate is the image. She has never told us what she thinks of us. She is the last great silent star. A ubiquitous, postmodern Garbo. Look at that face: the hooded eyes, the merest hint of a private smile, quizzical and knowing, amused and wary. It's an old expression on a young face. By instinct or design, Moss has understood a lesson from our clamorous, cheap-talking, opinion-clogged age - that less is more. ... Kate says nothing, but looks everything.

'You want to be like Kate Moss. Be yourself...' is a little cheap, especially since, as Gill so eloquently establishes in the rest of the piece, Moss has assiduously avoided the temptations of subjectivity. Compare a genuine visual artist like Moss with a dull anti-sensualist Confessor like Emin. Moss the artist is encumbered by psychological depth - 'all there is of Kate is the image' - but for quaint, Romantic Tracey, all the visual material - her 'Work' - is to be read in terms of an underlying celebrity-subjectivity. The better slogan would have been: you want to be like Kate Moss, be an object. Hers is the silence of the object - and also, perhaps, the silence of the drives that circulate around the object...

- The silence of the drives ... is not a silence which contributes to sense, and this is its most disturbing feature ... It does not tell us anything, but it persists.

- Mladen Dolar

August 11, 2006

Disco sublime

Blistering Junior Boys gig last night at the Luminaire.... When I saw Ariel Pink there a few months ago, his sublimitiy succumbed to poor sound. Any worries that the Junior Boys would go the same way were put to rest by the surprising but gratifying vivid physicality of their live sound. It is disco sublime, like an arctic encounter between Chic and Mr Fingers. A few initial technical hitches were soon brushed aside as the Junior Boys quickly imposed Canada's wide open spaces on dingy, claustrophobic London. The sound was as ice-white as Jeremy Greenspan's suit, as expansive as Canada's endless highways. Live performance gave new angles on old songs. They closed with 'Under the Sun', which was never one of my favourite tracks on Last Exit, but live it has a driving, widescreen sweep that recalls Simple Minds' New Gold Dream at its most epic...

August 07, 2006

Requiem for popular modernism

It's hard not to read Woebot's indispensable'Prehistory of British Electronic Music' as a requiem for popular modernism in British cultural life.

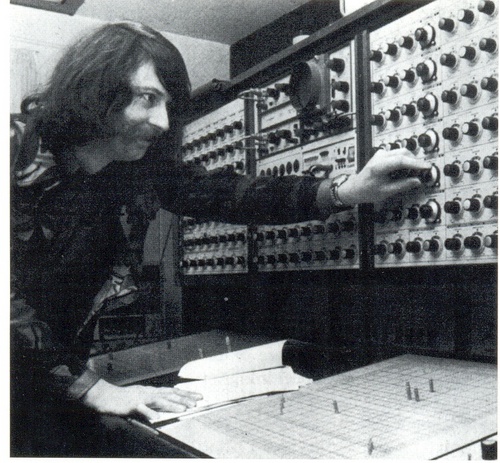

Matt argues that, by contrast with the US, where 'electronics seeped out of the Universities and Laboratories fairly early on and managed to permeate Soul (Tonto/Stevie Wonder/Syreeta), Jazz Funk (Dr.Partick Gleeson/Herbie Hancock) even Folk (Czaajkowski/Buffy Sainte -Marie)', electronic experimentalism was peripheral in Britain. That might be the case with Pop, but electronic experimentalism was subtly pervasive in the UK very quickly, because of the work of the Radiophonic Workshop. As I tried to suggest in the section about Delia Derbyshire I wrote for londonunderlondon, the Radiophonic Workshop's 'earworms' - its local radio idents as well as its better known TV themes and incidental soundscapes - were genuinely unheimlich, unhomely, a familar-alien presence that successfully insinuated itself into the interstices of the domestic environment at its most banal.

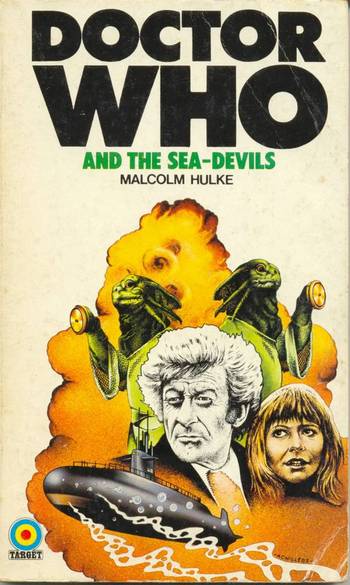

What was most remarkable about this is that it was incursion without entryism. There was no attempt to tone down the electronics in order to make them more palatable. On the contrary, as Nick Gutterbreakz pointed out in his excellent piece on the Workshop and Dr Who cover art, Malcolm Clarke's astonishing soundtrack for the Sea Devils 'made Throbbing Gristle look like a bunch of fucking pussies - three years before they even existed.'

What a contrast with the lame, sub-John Williams syrup that the BBC ladles over the current Dr Who series. This shrill, postmodern confectionery couldn't be less unheimlich. By firm contrast with the radiophonic's anempathic sounds, which rendered even the most everyday scene weird and alienating, the new music Tells You Exactly What to Feel; it's all too appropriate for the post-OC emotional pornography into which the series has devolved.

(Incidentally, the covers for the 70s Dr Who Target adaptations about which Nick wrote so lovingly form a similarly horrible contrast with the flashy Photoshop trash used on the book and DVD covers for the new series.)

UPDATE:

Jon Wozencroft replies:

- I have to take issue with you that "Electronic experimentation was peripheral in Britain"... another argument could be put forward that it was absolutely the foundation stone of how we presently navigate popular culture. Take "Telstar", where Joe Meek's production techniques find symbiosis with a news story-of-the-day. Then "Tomorrow Never Knows", in which the laddish roots of The Beatles flower into a strange meeting between Liverpudlian poetry and The Tibetan Book of the Dead. You could trace a definite line between all previous uses of electronics and how you end up with Cabaret Voltaire - "No Escape" being a key recording in this respect, a cover version of The Seeds.

In other words, just as you have the seedbed of works done by Tim Souster and Trevor Wishart in the 1970s, so too do you have smash hits like "Popcorn" by Hot Butter and the enormous impact of Boney M and then "I Feel Love" - although originated in Germany (there's another story), the main impact was felt in the UK.

In the USA, one of the most influential "electricians" is Curtis Roads, who does indeed operate out of a University context (Texas?), but then so does Wishart (York) as did Gavin Bryars (Leicester) and now does David Toop (LCC). It's not as simple as it looks.

It's also worth mentioning that there are loads of influential groups beyond Pulp that have come out of an academic context - notably Wire.

But if we are stretching the remit a bit here, let's go back to the Radiophonic Workshop and Dr. Who and make the connection with Bill Drummond and the KLF.

Nevertheless, I think it is worth making a distinction between sonic popular culture and Pop here. It seems to me that the whole of Sixties Pop experimentation was rendered conservative - even obsolete - in advance by Delia Derbyshire's Dr Who theme. It would be over 20 years before Pop - in the form of Acid House - would catch up with Derbyshire's electronic abstraction. The Radiophonic Workshop's 'peripheral' position (in relation to Pop spectacle) was precisely what allowed it to be pervasive at the level of the Sonic Unconscious.

UPDATE 2:

Jon Wozencroft repies again:

- Delia's theme music has a dimension with Pop in so much as it was etched on your brain, the mood was so powerful. I remember we used to try and re-enact it vocally as children, our first karaoke if you like, and even when we knew the theme tune backwards and the title sequence backwards, we would still hide behind the sofa in the living room when the programme came on, in homage.

It was always on early on a Saturday evening in those days. In an era (ear) of programming genius, it came on shortly after the football results. Also, the bitter aftermath of the 1963 extreme cold winter and the JFK assasination. An aspect you don't mention is the role of the Daleks in all this. (Years later, Gary Numan would emerge as "the human Dalek", but that's another story). The use of processed voice here is very significant and it also has an echo/collocation with the EVP recordings I gave you today. The Daleks were of course from another world, but the "am I human/am I a machine?" dichotomy is writ large here. In some preconfiguration of the post Lacan/Deleuzean "fold", language is lost and all that can be said is "exterminate, exterminate"!

I was still at (nursery) pre-school, and Kellogs cornflakes started a campaign whereby they gave you cardboard cut-out sections of a Dalek that you could collect and then reassemble to make your own miniature version. I might be wrong in this, but I seem to remember that this co-incided (co-insided) with the emergence of The Beatles as an electric force ("A Taste of Honey" by this time had become "A Hard Days Night") and the imminence of The Kinks.

The Kinks, I would imagine, were watching more episodes of Dr. Who than The Beatles had time to do.

August 04, 2006

Don't miss this

Really excellent documentary on art schools and Pop, presented by Jarvis Cocker, and featuring John Foxx and Jon Wozencroft.

August 03, 2006

The detective supposed to know

|  |

Bacteria grl makes her very welcome entry into the blogosphere, and responds to my post on Columbo and Ripley by raising the issue of the distinctive narrative structure of the Columbo series, in which 'the preparation and the murderer and the murder itself is always showed first, in many cases it is shown along with the opening credits, and often in a quite lurid style ... or if not lurid, in a fairly telescoped visual shorthand that displays all the elements of the crime with no dialogue or music, total silence with quick cuts.'

Columbo departs from the technique of 'reconstruction' upon which the Dupin/ Holmes mode of detective fiction was built. In The Mechanical Bride, McLuhan compares the sleuth of the Dupin/Holmes mode with the cinematographic apparatus itself:

- Edgar Allan Poe hit upon the principle of "reconstruction," or reasoning backwards, and made of it the basic technique of crime fiction and symbolist poetry alike. Instead of developing a narrative straightforward, inventing scenes, character, and description as he proceeds, in the Walter Scott manner, Poe said: "I prefer commencing with the consideration of an effect."

... The sleuth pursues his clues backward to the cause which produced them. He investigates the possible motive of each suspect. Then he assembles all these different perspectives as though he were piecing together a movie that had been shot in separate sections. When all is assembled, he then projects, as it were, the continuous film before the assembled guests at the scene of the murder. He relates the events in their true time sequence, thus automatically revealing the murderer.

It was Poe who discovered the technique of this intellectual cinematograph half a century before the movie camera was invented.

It's worth noting that the departure from this reconstructive technique is something else that Columbo has in common with Highsmith (and with their common ur-source, Crime and Punishment). Highsmith, too, completely abandons the whodunnit structure. Her novels are usually focalized through the subjectivity of the murderer, leaving us no option but to identify with him.

I think the effect of our seeing the murder first in the Columbo episodes is similar, in that we identify with the murderer, not with the detective.

Columbo is not like Dupin or Holmes, a 'gentleman aesthete' existing in his own lifeworld before being called in to solve a crime. Nor is he like Poirot, a bystander in the midst of an aristocratic revel asked to decide which of the his fellow leisure class hedonists is the murderer. Columbo exists only after the crime has been committed, almost as if he is a pure apparition of guilt. The model is the Poe, not of the Dupin stories, but of 'The Tell Tale Heart'. From the guilt-ridden perspective of the murderer, Columbo is not so much the one who knows as the one who must know.

In the classic 70s episodes, Columbo is rarely seen on his own. We typically do not see Columbo 'for himself', only for the criminal, leaving the possibility that the entire Columbo persona - his shambling manner, his absent mindedness, even his references to his wife - may all be a performance designed to disarm the murderer. Unlike middlebrow bores such as the insufferable Morse, Columbo is not 'a man of taste'; he has no psychological depth.

This lack of psychological depth, his reduction to pure function, make Columbo like the pyschoanalyst, i.e. the one in the structural position of one supposed to know. Columbo's deliberately irritating questioning technique - 'just one more thing' - is designed to produce discomfort rather than to elicit information. (The first mistake that the murderer makes is always to airily explain away some anomalous fact with which Columbo presents them. The murderer's flip readiness with an explanation, their willingness to implicate others, already constitutes a kind of admission of guilt. You always feel that they would be far better to simply scratch their heads and express bewilderement.) The plots usually turn on Columbo inducing the murderer to repeat (some aspect of) the crime, i.e. to confront the trauma they are seeking to escape. Like the successful analysand, they must retrospectively take responsibility for what happened: where It (the trauma-murder) was, there I shall be.

________________________________________________________________

Owen interestingly observes that a link between Columbo and Ripley is made in the films of Wim Wenders. Wenders' Wings of Desire features what is evidently a version of the Columbo character, whereas The American Friend is a somewhat loose adaptation of Ripley's Game. If both the Columbo series and the Ripley novels were American versions of European existential narratives, then Wenders' early films represented a complementary European fascination with the USA, America's rootlessness functioning both as an analogue for, and a solution to, West Germany's necessary postwar cultural amnesia.

If Wenders' humanism prevented him from capturing Ripley, it also caused him to miss Columbo. By showing 'Columbo tucking into currywurst at a Kreuzberg imbiss', Wenders precisely gives Columbo depth and an independent subjective life (some of the later Columbo episodes make the same mistake, and we see Columbo eating chili in restaurants etc). The 'angelic' side of Columbo does not consist in his 'really being a regular guy'; it is inseparable from his implacablity, his role as a psychological torturer.

(Wings of Desire has always struck me as appalling sentimentalized: like the 'Everybody Hurts' video, or one of those commercials which show that we might have different hopes and dreams but hey, we're all people, right? Kind of Epic Trite; no wonder he'd soon be working with U2.)

August 02, 2006

Conspicuous Force and Verminization

The paradoxical War on Terror is based on a kind of willed stupidity; the willed stupidity of wishful thinking. Only the logic of dreamwork can suture 'War' with 'Terror' in this way, since terrorists were, by classical definition, those without 'legitimate authority' to wage war. However, it is horribly evident for some while that a new, frighteningly facile, definition of Terrorism has come into play. What makes Terrorists terrorists is not their supposed lack of legitimate authority but their inherent Evil. We are ontologically Good; Good by our very nature, no matter what we do. We belong to an 'alliance of moderation' against the Axis of Evil. So when 'we' 'accidentally' level an appartment block full of children with our moderate bombs, we do not cease to be moderate. The difference between They, the Evil and We, the Good is, of course, intent; the Terrorists deliberately target civilians. This is their only aim, because they are Evil. Although we kill vastly more civilians, we do not intend to it, so we remain Good.

For the libidinal roots of this wishful thinking, we have to look beyond the foibles of individuals to the political unconscious of the hyper-militarized State. It is geared to deal with threats if they come from other armed States, so it pretends - deceives itself, and then attempts to deceive us - that this is in accord with the actual geopolitical situation. Condi's crocodile tears notwithstanding, the US, needless to say, is no position to condemn Israel's air strikes, since the Israeli bombings follow the War on Terror script to the letter. The conflict with Hezbullah turns into a destruction of Lebanese people and infrastructure, just as the struggle with Al Qaeda became a war on Afghanistan and Iraq. For the hyper-miltarized State , assymetry can only be thought of as an advantage: we have more and better weaponry than them, therefore we must win.

The stupidity here is evident, and multi-levelled. First of all, it involves a literal occlusion and suppression of Intelligence. Terrorism is a problem to be met with brute force rather with intelligence. Successfully defeating Terrorist groups is a long-term business, dirty, but above all, stealthy, invisible. But the War on Terror is inherently and inescapably Spectacular; it arises from the demands of the post 9/11 Military-Industrial-Entertainment Complex: it is not enough for the State to do something, it has to be seen doing something. The template here is Gulf War 1, which as both Baudrillard and Virilio knew, could not be understood outside logics of mediatization. Gulf War 1 was conceived of a kind of re-shooting of Vietnam, with better technology, and on a videogame desert terrain in which carpet bombing would be industrially effective. This is the kind of assymetry that the Military-Industrial-Entertainment Complex likes: no casualties (on our side).

The bringing to bear of what, following Veblen, we might call conspicuous force presupposes a second stupidity: the verminization of the Enemy. Before Gulf War 1 had even happened, Virilo saw the logic of verminization rehearsed in James Cameron's Aliens wherein the 'machinic actors do battle in a Manichean combat in which the enemy is no longer an adversary, a fellow creature one must respect in spite of everything; rather, it is an unnameable being that it is more appropriate to exerminate than to examine or analyse.' In Aliens, Virilio ominously notes, attacks on the 'family [form] the basis of ... necolonial intervention.' The teeming, Lovecraftian abominations which can breed much faster than we can are to be dealt with by machines whose 'awesome appearance is part of [their] military effectiveness.' Shock and awe.

Aliens was the moment in which a new mode of the Military-Industrial-Entertainment became visible. Virilio argued that Aliens' privileging of military hardware 'could only lead in the end to the extinction of the talking film, its complete replacement by film trailers for hardened militarists'. In fact, the talking film has been replaced by the shoot-em-up videogame whose picnoleptic delirium is flat with the prosecution of the Sega-Sony-CNN war. 'Realists' who attacked Baudrillard and Virilio for their insistence upon the fact that war is now constitutively mediatized missed the point that hyperrealization is precisely what permits the production of very real deaths on a mass scale.

Verminization not only transforms the Enemy into a subhuman swarm that cannot be reasoned with, only destroyed; it also makes 'us' into victims of its repulsive, invasive agency. As Virilo perspicaciously observed, Aliens itself operated 'a bit like a Terrorist attack. Women and children are slaughtered in order to create an irreversible situation, an irremediable hatred. The presence of the little victim has no theatrical value other than to dispose us to accept the madness of the massacres...'

While 'we' have 'families' who are being senselessly killed, vermin have neither memory nor motive; they act unreflexively, autonomically. Their extermination is a practical problem; it is simply a matter of finding their nests and using the right kind of weapon. Applying this thinking to Hezbullah or any other group is appalling racism, naturally, but also astonishingly poor strategy, implying no understanding of Terrorism whatsoever. Destroy all the infrastructure, kill all the operatives: but you will have only created more Images of atrocity; indestructrible and infinitely replayayble repositories of affect, which, by demanding response and producing (a usually entirely justified) recrimination, act as the best intensifiers and amplifiers of Terror.