August 15, 2006

'Fashion's Great Sphinx'

|  |

- The masses have been "seduced" in the modern era by only two great events: the white light of the stars and the black light of terrorism. These two phenomena have much in common. Terrorist acts, like the stars, "flicker:" they do not enlighten, they do not radiate a continuous, white light, but an intermittent, cold light; they disappoint even as they exalt; they fascinate by the suddenness of their appearance and the imminence of their disappearance. And they are constantly being eclipsed as they each try to outdo each other.

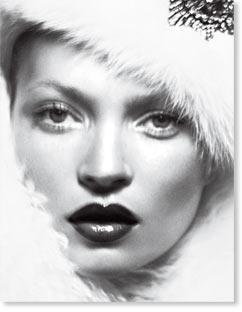

The great stars or seductresses never dazzle because of their talent or intelligence but because of their absence. They are dazzling in their nullity, and in their coldness - the coldness of makeup and ritual hieraticism (rituals are cool, according to McLuhan).

- Baurillard, Seduction

We still have the terrorism, but we no longer have the seduction of the Star. Or such seduction is rarer, far rarer, than it was in 1977.

'The death of the stars is merely punishment for their ritualized idolatory,' Baudrillard went on. 'They must die, they must already be dead - so that they can be perfect and superficial, with or without makeup.' At this time, Baudrillard could still imagine a death that 'itself shines through its very absence, ... turned into a brilliant and superficial appearance'. This was still the age of cinema, and Seduction would turn out to be its epitaph. Neither cinema, nor seduction, nor the Star, would survive the period of TVerite celebreality Baudrillard was already anatomizing. A different death awaited, no longer a death that was brilliant and superficial, but the death represented by banal psychological depth.

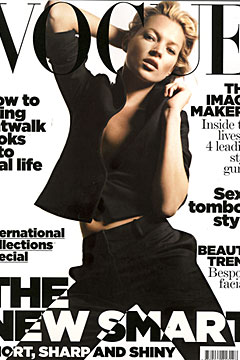

A year ago, the tabloids, with their customary solemn hysteria, passed a death sentence on Moss's career --- but here she is, in August 2006, on the front of both Vogue and Vanity Fair. In fact, Vogue informs us that, in addition to being its cover-star for a record-breaking 23rd time, Moss features in no less than eight adverts this month: 'Dior on page 11, Louis Vuitton on page 15, Versace on page 49, Burberry on page 50, Stella McCartney on pages 86 and 87, Longchamp on page 139, Belstaff on page 240 and 241 and Rimmel on page 389.'

A A Gill's excellent puff-piece on Moss in Vanity Fair - accompanying some wonderful photographs which have Moss sumptuously re-staging the Silent era Star poses of Garbo, Dietrich and Harlow - stresses that it is Moss's notorious refusal to speak that guaranteed her sublimity remained unassailable. Moss's career as Image would indeed have died if she had taken the tabloid bait and entered its Confessional. To respond to the demand to speak, to have herself assumed the banalizing soap opera role of 'troubled star' which the tabloids had scripted for her, would have won her the temporary sympathy of the populist big Other, but would have permanently cost her the aristocratic cache which keeps the high fashion contracts coming in. The tabloids have always resented Moss because she has never been their Thing; she passes through their pages, immaculately immune to all their anti-Glam techniques (Gill: 'However hard they tried - and they tried - she's incapable of taking a grim, morning-after, baggy, saggy, up-the-nose shot'). Gill again:

- Moss's zipped-lipped lack of cant and hypocrisy implies that she won't be held responsible for society's worries about drugs or anorexia or family values, or its fears for its children. She's a fashion model, not a role model. You want to be like Kate Moss? Be yourself. All there is of Kate is the image. She has never told us what she thinks of us. She is the last great silent star. A ubiquitous, postmodern Garbo. Look at that face: the hooded eyes, the merest hint of a private smile, quizzical and knowing, amused and wary. It's an old expression on a young face. By instinct or design, Moss has understood a lesson from our clamorous, cheap-talking, opinion-clogged age - that less is more. ... Kate says nothing, but looks everything.

'You want to be like Kate Moss. Be yourself...' is a little cheap, especially since, as Gill so eloquently establishes in the rest of the piece, Moss has assiduously avoided the temptations of subjectivity. Compare a genuine visual artist like Moss with a dull anti-sensualist Confessor like Emin. Moss the artist is encumbered by psychological depth - 'all there is of Kate is the image' - but for quaint, Romantic Tracey, all the visual material - her 'Work' - is to be read in terms of an underlying celebrity-subjectivity. The better slogan would have been: you want to be like Kate Moss, be an object. Hers is the silence of the object - and also, perhaps, the silence of the drives that circulate around the object...

- The silence of the drives ... is not a silence which contributes to sense, and this is its most disturbing feature ... It does not tell us anything, but it persists.

- Mladen Dolar