August 29, 2007

Fire dance with me

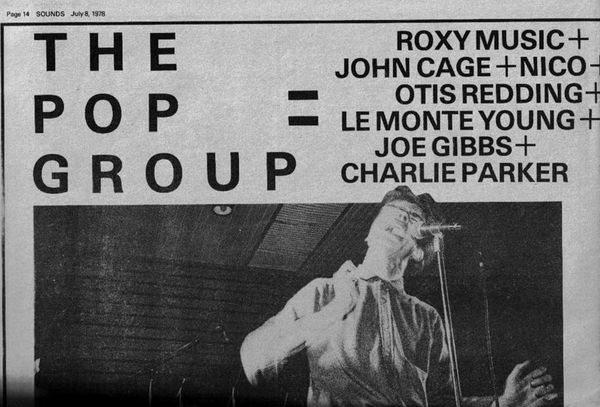

Me on The Pop Group (for younger readers: the kind of thing folk had to make do with before pop reached its glorious zenith with Paris Hilton and Backstreet Boys) in Fact.

Excellent hauntology piece by Dan at the End Times.

Speaking of hauntology, I should have mentioned before that I'm talking at this in September.

UPDATE

I didn't realise these stunning Pop Group videos had surfaced on Youtube until I saw this....

August 24, 2007

Some hauntological confluences

Suffolk Hauntology (slight return)

Some photographs by Bacteria Grrl ...

... of Leeks Hill wood in Woodbridge/ Melton, as featured on Eno's On Land and mentioned in previous dispatches...

... and of some more phantom-fragment boats in the Deben:

'There's something very cinematic about these pieces, though the music sounds nothing like a soundtrack': sonic hauntology (new and old)

|  |

Rolan Vega's Documentary, which I've just reviewed for the Wire, appears to have arrived at a Library Music-inspired syn(thesizer)aesthetic very similar to Ghost Box, but by an independent route. Like Ghost Box, Mordant and Foxx's Tiny Colour Movies, Vega's sound has a relation to film and photography, although with Vega the visual is an entirely virtual component of the audio. The sounds - as fragile and evocative as scratched celluloid - are inspired and informed by images, or by music that once accompanied images. 'Is "Documentary" a collection of works for actual short films and media, or an attempt to pay tribute to the synth epics of media music's past?,' asks the intriguing press release. 'Both', it answers, rightly; and, rather like Mordant's Dead Air, Documentary feels like a tour through a decaying archive that produces strange and beautiful patterns as it disintegrates.

Jeck's Stoke, which I recently - and belatedly - discovered courtesy of Touch's Jon Wozencroft, is another oneiric drift through the archives. Listening to the record - or rather gradually being possessed by it - over the course of the last few weeks has confirmed my initial impression that any serious discussion of sonic hauntology cannot ignore Philip. His sound could be characterized as a dyschronic, disembodied hip hop (a dream hop?) - Jeck 'started using record players in the early eighties after hearing mixers like Walter Gibbons and Larry Levan and Grandmaster Flash' - produced using dansette turntables, FX units and records found in charity shops. (Imagine what you thought middlebrow mediocrities DJs Shadow and Spooky sounded like before you actually heard the records). But Jeck's methodology - he composes his records largely from edits of live performances - makes it equally plausible to describe him as a junk shop counterpart of Teo Macero, the legendary sonic sorcerer who conjured wondrous unlive collages from Miles Davis' studio playing. (It's not at all coincidental that Eno mentioned Macero on the sleeve notes to On Land.) Both the hip hop DJ and the studio remixer are experts in the necromantic art of manipulating sonic unlife: the DJ performs live manipulations of Read Only Memory recordings, whereas the remixer takes a live performance out of the lived duration of so-called real time into the unlive no-time of the studio. Like sonic hauntology in general, Jeck - a steampunk surgeon of sound, a surfer of surface noise - is at the confluence of these two approaches. Stoke is often keeningly plaintive, although there is an impersonal, mechanical quality to the melancholy, almost as if it belongs to the aged machinery and the recovered objects themselves. Philip refers to the sonic sources he uses as 'fragments of memory, triggering associations' but it is crucial that the memories are not necessarily his; the effect is is sometimes like sifting through a box of slides, photographs and postcards from anonymous people, long gone.

In his excellent review of Stoke for Pitchfork, Mark Richardson drew out the virtual-visual dimension of Philip's work (remember that Jon W always insists that Touch is an audio-visual label):

- Listening to his most recent album, Stoke, it's hard not to think about Jeck's background in visual art, and how it informs his audio work. There's something very cinematic about these pieces, though the music sounds nothing like a soundtrack. Some of the visual referencing could come from the regular pops and scrapes in the vinyl, which are reminiscent of the sound of a spool of film being fed into a projector. Jeck's endlessly rotating platters, like the whirr of moving film, serve as a constant reminder of the time-based nature of the medium.'

'You've always been the caretaker...'

The audio-visual dimension of sonic hauntology perhaps arises from an affinity with the inherently dyschronic nature of film (and television insofar as it is pre-recorded). I concluded the remarks I made a long time ago on Teo Macero by comparing him to Kubrick. Kubrick always repudiated without any compunction the live, theatrical aspects of cinema, treating actors as re-(com)posable resources rather than as artists, the integrity of whose performance had to be respected. Kubrick's own films were themselves meditations on life as automatism, on the insistence of hauntological structure beneath the illusion of agency.

I tried to draw this out in my contribution to the Spectral Spaces issue of Perforations, which was the latest of my many visits - and surely not the last - to the Overlook. What is the Overlook - its corridors, as King put it, extending in time as well as space - if not an audio-visualization of dsychronia? (Venice in Roeg's Don't Look Now, which I watched this week for the first time in ages, is of course another dyschronic labyrinth, in which time's out-of-joint fatality is rendered as repetitions of colour and tricks of sound: Roeg took advantage of the way that Venice acted as a 'sound maze', an architectural schizophonizer that separates sounds from their sources, setting up a duplicitous, hyper-doubled sonic space).

'Places that do not exist and were never going to exist'

Owen's piece in Spectral Spaces explores a special kind of ghost town: 'places which do not exist and were never going to exist', the British New Towns that were planned but not built. Contemplation of the plans 'brings the contemporary reader up against the sheer strangeness of mid-century normality': these monuments to a rejected British Modernism are relics of a popular utopianism that was at its most potent when most quotidian. Owen notes that Ghost Box/ Belbury Poly's re-dreaming of a postwar public space revives the possibility - unthinkable now, what could be more anathema to popist orthodoxy? - of a benign paternalism (I will return to this in my next post).

In postmodernist Britain - where, as as Owen puts it, 'nothing can happen ..., nothing has ever happened' and the '20th century was a bad dream', where you can buy a latte on every corner but half the population dare not leave their houses at night - the remains of modernism are typically treated with contempt and revulsion. This returns us to Owen's old question: what would have happened if the population of modernist Britain's council estates, tower blocks and New Towns had embraced popular modernism instead of yearning for the replicant false-memory sim-paradise of a dissolved organic community? Post-punk was already an ambivalent requiem for the destroyed and despoiled dreams of a modernist Britain; you can hear its broken glass trodden underfoot not only in The Slits'/ Bovell's 'New Town', but also in Hannett/ Joy Division's Manchester. One of Savage's best pieces on JD centres on Bernard Sumner's anguish about his old area being replaced by tower blocks.

'Watching the reel as it comes to a close ...'

'Aesthetic hauntology rarely deals with actual instead of imagined death, but in Joy Division ... it must', writes Ian Mathers in his (un)timely excavation of hauntology and Closer in the Spectral Spaces issue of Perforations. Ian focuses close attention on the preternatural qualities of Curtis' recorded voice - pitched down below his natural range under the tutelage of Hannett - as hauntological trace. 'The voice is both a more and less sure guarantor of presence than the image; if a loved one passes away their pictures may pain us, but how much worse is it to call their number one more time and hear their voice on their answering machine? How much worse to hear that voice on the radio, sounding already gone?' Part of what makes Closer so harrowing is its quality of sounding like recorded message from one who was already dead, a Waldemar-like seance with a corpse that has found a voice. In his lyrics Curtis dwelt on the theme of being-a-prerecording, of living life as if it were a film, of being the only living entity in a world of zombies - a sense interred and distilled in the glacially fatalistic cata-tone of his voice, about which Ian writes so eloquently.

An impressario of Death

Curtis, Hannett, Gretton, now Wilson - premature death has always shadowed Factory. Morley's Guardian obituary for Wilson read like a reprise of Nothing, his masterpiece, which was as darkly vivid as Words and Music was brightly dull. Wilson might have exploited Curtis' death - casting Morley as mythographer-in-chief - but his motive was not money.

As Momus put it in his tribute, Wilson kept business in its place. He stood on the other side of a cultural economic fault-line, his sensibility formed long before Business Ontology totally colonized the post-Thatcherite unconscious. Making money was a means to a series of ends that were artistically extravagant, culturally flamboyant.

It was to Wilson's credit that he was never ashamed of his background; instead of indulging in tedious guilt trips or pop(ul)ist gestures, he used what resources he had to support the production of popular art works that anyone could buy. Wilson might have been an inveterate show-off, but the audience he courted were working class youth. He might have wanted to beguile and entrance them, to impress them with his learning and his eloquence, but better that - far better that - than pretending to be more stupid than you are, as more or less every educated person is required to do to get on in Old Media today; and, as Owen says, Wilson never thought that 'never assumed that football fans, ex-dock clerks and so forth wouldn't 'get' such far from 'upbeat' ideas or artefacts as Durrutti, Fortunato Depero, the SI.' Irritating, provoking, captivating, Wilson represented a positive paternalism. On which, see the next post: Marxist Supernanny.

August 17, 2007

'a rupturing of this collective amnesia'

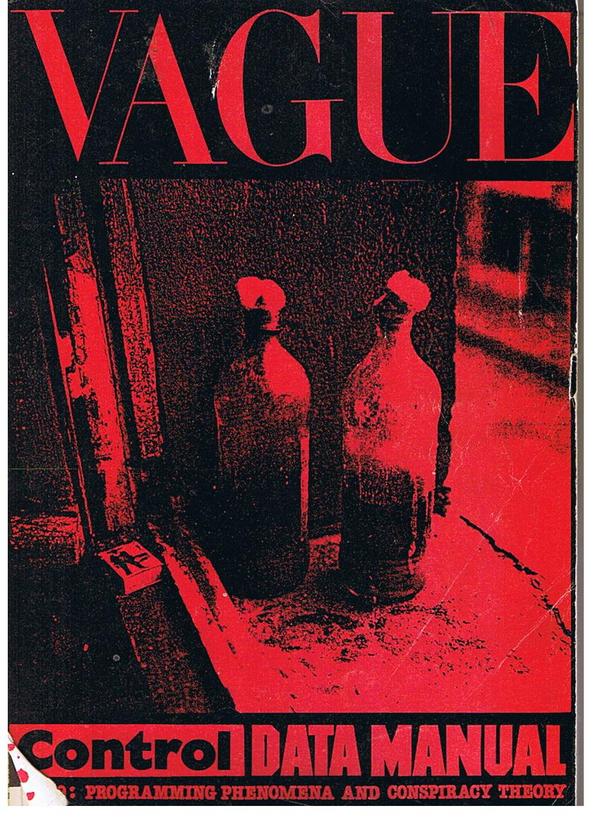

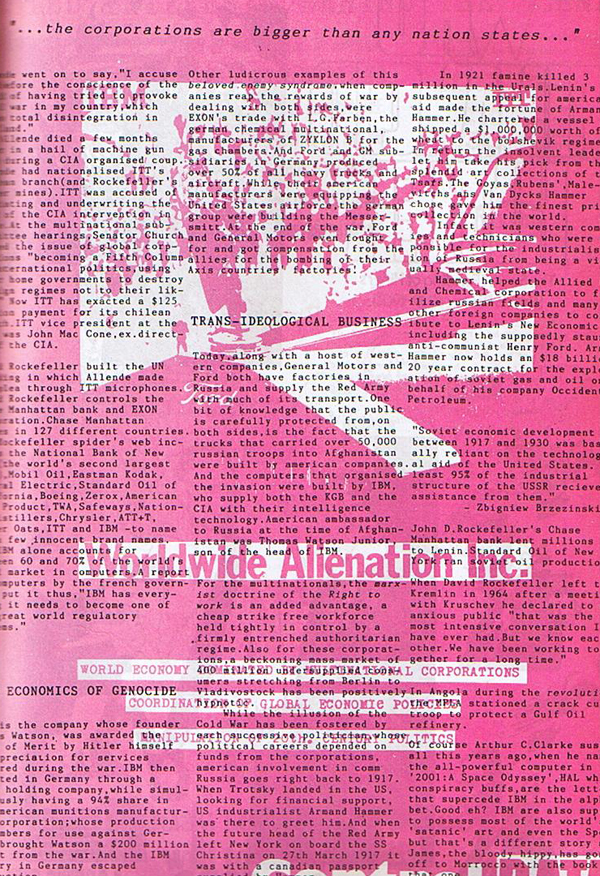

- 'Tom Vague is a fiction...' (Mark Downham, Vague 21: Cyberpunk)

... or Tom Vague had fictionalized himself, casting himself as Willard in a comic strip version of Apocalypse Now set in late Cold War Stoke Newington, (and not entirely as a joke); or he had induced others to weave him into their fictions, fictions that he, TV, dole culture auto-didact, had himself published in zines that became much more than zines... (Of course he knew full well that - in an age of simulation which he had a better handle on than most - fictions were more than fictions...)

The small bands of interference realise they are totally unprepared for what lies ahead.

It's the mid-eighties. London before Starbucks. Deep into the perma-midwinter of white queen Thatcher's New Bad Dream, GB 84-85-86-87-88-89... Postwar labour has just died with the Miners' Strike; and, jeered along by a neurologically-damaged, military-Keynesian PKD-Ballard actor-president in the White House, the U.S.S.R. is set to self-destruct, with market Stalinism already preparing it to become a neo-liberal lab. All that is sold is melting into a cyberspace precorporated into Capital, but we have no idea how bad things are going to get.

- From punk to k-punk

Vague did... While all (other) eyes were on the rearview mirror - Very Old Media was being brutally cyberneticized at Wapping, the Old Left was already obligingly distintegrating into a nostalgia cult - Vague was absolutely of its time and therefore ahead of it. (As McLuhan said, a prophet is simply someone who can see what is right in front of them.) Excoriating rock und roll for failing in its millenarian promises, Vague had long since ceased to be a fanzine and had become a mutating (Control/Data/Cyberpunk) manual and videodrome console.

The pages, text and images teeming over one another, often with little regard for legibility, were like the visual analogue of Mark Stewart's As the Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade (Stewart was himself a sometime contributor), fragmentary signal bleeding out through noise. Vague understood that the (70s) stand-off between Old Media and fanzines presaged a conflict that you are participating in now. Punk only mattered if it could become cyberpunk, which Vague knew had nothing to do with airbrushed Californian dreamin', and everything to do with Capital as super-sentient planetary monstrosity - 'the hugeness, the humming, a torrent of pure light, a semiotic web, a global nervous system thinking for itself' (Mark Downham, 'Cyberpunk') ... And k codes for cybernetics...

British cyberpunk was invented by pulp modernist bricoleur Mark Downham in the pages of Vague. Certainly, there would have been no Ccru without Downham's two treatises, 'Videodrome: the Thing in Room 101' and 'Cyberpunk', which, - years before such connections would be academic-rusted into familiarity - patched together Gibson, Debord, Moorcock, Tesla, Baudrillard, Apocalypse Now, in a form that accelerated what Ballard had done in The Atrocity Exhibition.

- From cyber-punk to hauntology

Cut to now, where the once crudely cut-and-pasted neo-liberal reality picture has stabilised and naturalised itself, positing itself as the terminal towards which the bullet train of history has always been heading. The only class war violence you will see on television is on re-runs of Billy Elliot. Rioting is unimaginable, but it's normal for fourteen year old black kids to be shot. Kapital Utopia UK.

Welcome to Liberty City....

I finally get to meet Tom Vague, sitting outside the re-located Chelsea College of Art on Millbank. Still as speed-thin as the old pix, only slightly greyer (aren't we all?) he's quiet as Kurtz, as withdrawn as you'd expect someone who is part fiction, part writer, to be. He has a writer's nerves about public speaking. I ask him what he's been doing, delighted that he's neither been invalided-out on some psych ward, nor incorporated into some nu-meeja niche, or worse - delighted, that is to say, that he's avoided the fates you fear for the casualties of capitalist realism's pacification program...

I'll find a key and try to get out of this dormitory

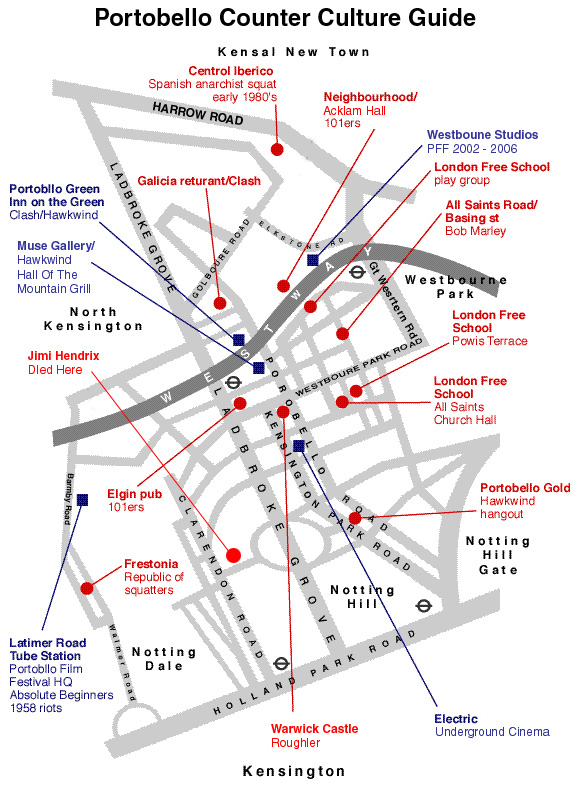

The latest version of Tom Vague is a psychogeographic tour guide. He's been invited to Chelsea by John Cussans to present a version of his meticulous, metamorphosing, sprawling pulp history of Notting Hill. Is this pysychogeography or hauntology?

In London, even the spectral streets are overcrowded. The air is thick with ghosts in Notting Hill... The shades of Jagger and Fox, who sleazed into each other and ended the Sixties in Performance, will always stalk Powis Square; the punky reggae party brewed up here, in the Ballard (High Rise/ Concrete Island) zone marked by the Trellick tower and the Westway, and some relics of that fission - Dub Vendor, the Rough Trade shop - still notionally survive, if now only the simulacrum-shell of their former selves. Vague tells us that the Trellick Tower haunted British culture even before it was built, Ian Fleming naming one of James Bond's most famous adversaries after of its architect, (Erno) Goldfinger. It's no accident that the Richard Curtis/ New Labour/ neo-liberal theme park - Vague calls it Notting Hell - has been erected here, the former site of so many riots and insurrections.

The point of TV's tour is to stir up the insurrectionary ghosts so that they contest the space, cultural as well as physical, now owned by middle mass poster boys for Brown's picture postcard London, open for business but closed to anything else. Tom Vague 2007 is much more forgiving to r and r than he was in 1987 (it was TV who said that Baader Meinhof was what W Germany had instead of punk. He says now that he used to regard Baader Meinhof as the real deal and the punk Thing as some commodified Spectacular distraction, but not any more...) The difference between the 80s and the 00s is perhaps the difference between mourning and melancholia. The Eighties counterculture was still flash-lit by the dimming afterglow of (post)punk, making the contrast between the promises of Then and the realities of Now all the keener. A new reality picture was being imposed, violently, but something else could still be remembered. After twenty years of capitalist realism, Thatcher's mantra - there is no alternative, a self-fulfilling prophecy feeding the seamless forcefield of the OedIPod - has gained in hyperstitional potency. The reason all these ghosts matter, the point of saying It wasn't always like this, is not that it was better then, let's go back, but to remind ourselves that it doesn't have to be this way... The ghosts that should most haunt us are the spectres of events that have not yet happened...

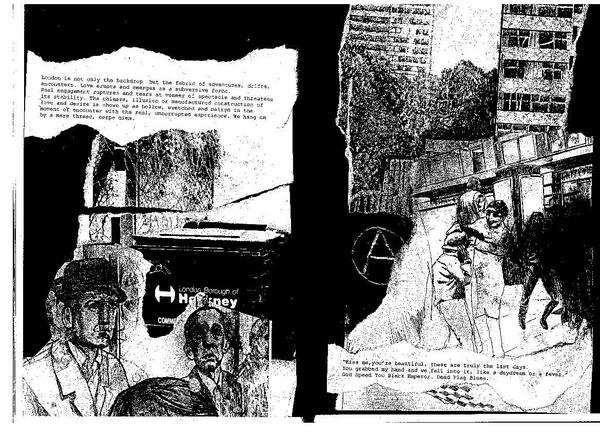

While waiting for Vague's talk, we meet another of London's hauntologists, Laura Oldfield Ford, the producer of Savage Messiah zine, now on its 8th issue. Each edition is devoted to a particular area of London, this time E8. Savage Messiah is like Heronbone with politics and pictures, Burial's London in words and image instead of sound. The collage form - text, photographs, Laura's own drawings - decomposes London from seamless, already-established capitalist reality into a riot of potentials, the city rediscovered as a site for drift and daydreams, a labyrinth of side-streets and spaces resistant to the process of gentrification and 'development' set to culminate in the miserable synchronized SF Capital festival of 2012.

- Perhaps it is here that the space can be opened up to forge a collective resistance to this neo liberal expansion, to the endless proliferation of banalities and the homogenising effects of globalization. Here in the burnt out shopping arcades, the boarded up precincts, the lost citadels of consumerism one might find the truth, and a new space opened up, there might be a rupturing of this collective amnesia.

Available from Savagemessiah[at]hotmail.co.uk

August 15, 2007

Australia and Class Update

Andrew Parker comments:

- The class mobility in Australia is probably derived from the basis of its economy and the relative lack of dialect. The Australian economy is predominantly driven by agriculture and mining. This means that many of the families capable of sending their children to private schools are involved in ‘blue-collar’ industries. This has probably helped ensure that it is only possible to discern that someone has attended a private school by judging their deportment, rather than their accent. The ‘branding’ effect of accent – that nominates region and class – hasn’t been discussed at length so far, perhaps because it is taken for granted in Britain.

... Latham lost the election because he was portrayed as an unstable hot-head who would destroy the economy and cause interest rates to rise. Sadly people’s dismay over Australia’s involvement in the Iraq war was subsumed by their concern for their mortgages.

Meanwhile, Emmy Hennings responds to Love and Terrorism's objections...

(I've had a great deal of correspondence recently, so if you've written in and I haven't responded yet, apologies, I'm getting to it...)

UPDATE 2

Andrew Parker adds:

- Class mobility looks set to continue in Western Australia. The current mining boom – in combination with a culture that promotes the idea that everyone should attend University – has produced a shortage of manual labourers such as plumbers, bricklayers and carpenters. This shortage has dramatically increased the incomes of manual labourers, with many of them earning more than University lecturers. The relative wealth of miners and labourers has led to an increase in house prices as many people choose to invest in property; the house prices in the capital of Western Australia have almost doubled in the last three years. The decision of many people to subdivide their land and build units/apartments has also increased the demand for manual labourers. Unfortunately, this booming economy is leaving many people and professionals behind. For example, there is an ongoing shortage of teachers due to many people either working for the mining companies so they can afford to continue living in the state, or leaving the state altogether.

August 12, 2007

Choose your weapons

People are often telling me that I ought to read Frank Kogan’s work, but I’ve never got around it. (Partly that’s because, Greil Marcus apart, I’ve never really tuned into much American pop criticism at all, which in my no doubt far too hasty judgement has seemed to be bogged down in a hyper-stylized faux-naif gonzoid mode that has never really appealed to me.) The – again, perhaps unfair – impression I have is that, in Britain, the battles that Kogan keeps on fighting were won, long ago, by working class autodidact intellectuals. No doubt the two recent pieces by Kogan that Simon has linked to are grotesquely unrepresentative of his work as a whole (I certainly hope so, since it is difficult to see why so many intelligent people would take his work seriously if they weren’t), but it’s hard not to read them as symptomatic, not only of an impasse and a malaise within what I now hesitate to call ‘Popism’, but of a far more pervasive, deeply-entrenched cultural conservatism in which so-called Popism is intrinsically implicated.

Remember, in the immediate wake of 9/11, all those po-faced Adornoite proclamations that there would be ‘no more triviality’ in American popular culture after the Twin Towers fell? There can be few who, even when the remains of the Twin Towers were smouldering, really believed that US pop culture would enter a new thoughtful, solemn and serious phase after September 11th – and it’s surely superfluous to remember, at this point, that what ensued was a newly vicious cynicism soft-focused by a piety that only a wounded Leviathan assuming the role of aggrieved victim can muster – but would anyone, then, have believed that, only six years later, a supposedly serious critic would write a piece called ‘Paris [Hilton] is our Vietnam’ … especially, when, in those years, there has, like, been another Vietnam. What we are dealing with in a phrase like ‘Paris is our Vietnam’ is not trivia - this isn’t the collective narcissism of a leisure class ignorant of geopolitics - but a self-conscious trivialization, an act of passive nihilistic transvaluation. Debating the merits or otherwise of a boring heiress have been elevated to the status of a political struggle; and not even by preening aesthetes in some Wildean/ Warholian celebration of superficiality, but by middle-aged men in sweat pants, sitting on the spectator’s armchair at the end of History and dissolutely flicking through the channels.

The end of history is the nightmare from which I am trying to awake.

At least the ‘Paris is Vietnam’ piece laid bare the resentment of resentment that I have previously argued is the real libidinal motor of ‘popism’ – ‘we love Paris all the more because others hate her (but luckily we loved her any way, honest!)’ But this latest piece Simon has linked to is, if anything, even more oddly pointless and indicative . Unlike the pleasantly mediocre Paris Hilton LP, the ostensible object of the piece, Backstreet Boys’ single ‘Everybody (Backstreet’s Back)’ is actually rather good. Practically everyone I know liked it. The problem is the idea that saying this is in some way news in 2007. No word of a lie, I had to check the date on that post, assuming, at first, that it must have been written a decade ago.

|  |

The article makes me think that, if the motivating factor with British popists is, overwhelmingly, class, with Americans it might be age. Perhaps those a little deeper into middle age than I am were still subject to the proscriptions and prescriptions of a Leavisite high culture. But it seems to me that popists now are like Mick Jagger confronted with punk in 1976: they don’t seem to realise that, if there is an establishment, it is them. Even if the ‘Nathan’ with whom Kogan debates exists - and I’ll be honest with you, I’m finding it hard to believe that he does - his function is a fantasmatic one (in the same way that Lacan argued that, if a pathologically jealous husband is proved right about his wife’s infidelities, his jealousy remains pathological): for popists to believe that their position is in any way challenging or novel, they have to keep digging up ‘Nathans’ who contest it. But, in 2007, Nathan’s hoary old belief that only groups who write their own songs can be valid has been refuted so many times that it is rather like someone mounting a defence of slavery today – sure, there are such people who sold such a view, but the position is so irrelevant to the current conjuncture that it is quaintly antiquated rather than a political threat. There may be a small minority of pop fans who claim to hold Nathan’s views; but, given the success of Sinatra, the Supremes, Elvis Presley and the very boybands that popists think it is so transgressive to re-evaluate, those views would in most cases be performatively contradicted by the fans’ actual tastes. (Kogan does grant that the problem is not so much fans' tastes as their accounts of them - but the unspoken assumption is that it is alright, indeed mandatory, to contest male rock fans' accounts of their own tastes, but that the aesthetic judgements of the figure with which the popist creepily identifies, the teenage girl, ought never to be gainsaid.) (The other irony is that, if you talk to an actual teenager today, they are far more likely to both like and have heard of Nirvana than they are the Backstreet Boys.)

The once-challenging claim that for certain listeners, the (likes of) Backstreet Boys could have been as potent as (the likes of) Nirvana has been passive-nihilistically reversed – now, the message disseminated by the wider culture - if not necessarily by the popists themselves - is that nothing was ever better than the Backstreet Boys. The old high culture disdain for pop cultural objects is retained; what is destroyed is the notion that there is anything more valuable than those objects. If pop is no more than a question of hedonic stim, then so are Shakespeare and Dostoyevsky. Reading Milton, or listening to Joy Division, have been re-branded as just another consumer choice, of no more significance than which brand of sweets you happen to like. Part of the reason that I find the term ‘Popism’ unhelpful now is that implies some connection between what I would prefer to call Deflationary Hedonic Relativism and what Morley and Penman were doing in the early 80s. But their project was the exact inverse of this: their claim was that, as much sophistication, intelligence and affect could be found in the Pop song as anywhere else. Importantly, the music, and the popular culture of the time, made the argument for them. The evaluation was not some fits-all-eras a priori position, but an intervention at a particular time designed to have certain effects. Morley and Penman were still critics, who expected to influence production, not consumer guides marking commodities out of five stars, or executives spending their spare time ranking every song with the word ‘sugar’ in it on live journal communities that are the cyberspace equivalent of public school dorms.

Whereas Morley and Penman (self-taught working class intellectuals both) complicated the relationship between theory and popular culture with writing that – in its formal properties, its style and its erudition, as well as in its content - contested commonsense, Deflationary Hedonic Relativism merely ratifies the empiricist dogmas that underpin consumerism. More than that. Owen has astutely observed that, in addition to reiterating the standard Anglo-American bluff dismissal of metaphysics, the Deflationary Hedonistic Relativist disclaiming of theory (‘we just like what we like, we don’t have a theory’) uncannily echoes the dreary mantras of the average NME Indie band: ‘we just do what we do, anything else is a bonus’, ‘the music is the only important thing’. In the UK, the rhetorical fight between ‘Popists’ and Indie is as much a phony war as the parliamentary political punch and judy show between Cameron’s Tories and Brown’s New Labour: a storm in a ruling class tea-cup. In both cases, the social reality is that of ex-public schoolkids carrying on their inter-House rivalries by other means. In the case of both Indie and Popism, there is a strangely inverted relationship to populism and the popular. While the ‘Popists’ claim to be populist but actually support music that is increasingly marginal in terms of sales figures, the Indie types claim to celebrate an alternative while their preferred music of choice (Trad skiffle) has Full Spectrum Dominance (you can’t listen to Radio 2 for fifteen minutes without hearing a Kaiser Chiefs song). In many ways, because it was attempting to analyse a genuinely popular phenomenon, Simon’s defence of Arctic Monkeys was more genuinely popist than all of the popist screeds on Paris Hilton’s barely-bought LP – but of course much of the impulse behind them was the ultra-rockist desire to be seen thumbing one’s nose at critical consensus. Witness the genuinely pathetic – it certainly provokes pathos in me – attempt to whip up controversy about the workmanlike plod of Kelly Clarkson, on a blog which, in its combination of hysterical overheating and dreary earnestness, is as boring as it is symptomatic – though, I have to confess I have never managed to get to the end of a single post, a problem I have with a great many ‘popist’ writings, including the magnum opus of popism, Morley’s Words and Music.

Much as he occasionally flails and rails against popist commonplaces (see, for instance, his recent – I would argue unwarranted – attack on Girls Aloud), Morley is as deeply integrated into Deflationary Hedonic Relativist commonsense as Penman is excluded from it. What was the strangely affectless Words and Music if not a description of the OedIpod from inside? All those friction-free freeways, those inconsequent consumer options standing in for existential choices... Yet Morley is still a theorist of the ends of History and of Music, still too obviously in love with intelligence to be fully plugged into the anti-theoretical OedIpod circuitry. Even so, Ian’s silence speaks far louder than Morley’s chatter, and, after my very few dealings with Old Media, I’m increasingly seeing Ian’s withdrawal, not as a tragic failure, but as a noble retreat.

All of UK culture tends to the condition of the clip show, in which talking heads – including, of course, Morley - are paid to say what dimwit posh producers have decided that the audience already thinks over footage of what everyone has already seen. I recently had dealings with an apparatchik of Very Old Media. What you get from representatives of VOM is always the same litany of requirements: writing must be ‘light’, ‘upbeat’ and ‘irreverent’. This last word is perhaps the key one, since it indicates that the sustaining fantasy to which the young agents of Very Old Media are subject is exactly the same as the one in which popists indulge: that they are refusing to show ‘reverence’ to some stuffy censorious big Other. But where, in the dreary-bright, dressed-down sarky snarky arcades of postmodern culture, is this ‘reverence’? What is the postmodern big Other if it is not this ‘irreverence’ itself? (Only people who have not been in a university humanities dept for a quarter-of-century – i.e. not at all your bogstandard Oxbdridge grad Meeja employee/ leisure-time popist – could really believe that there is some ruthlessly-policed high culture canon. When Harold Bloom wrote The Western Canon is what as a challenge to the relativism that is hegemonically dominant in English Studies.) I’ve quickly learned that ‘light’, ‘upbeat’ and ‘irreverent’ are all codes for ‘thoughtless’ and ‘mundanist’. Confronted with these values and their representatives – who, as you would expect, are much posher than me - I often encounter a cognitive dissonance, or rather a dissonance between affect and cognition. Faced with the Thick Posh People who staff so much of the media, I feel inferiority – their accents and even their names are enough to induce such feelings – but think that they must be wrong. It is this kind of dissonance that can produce serious mental illness; or – if the conditions are right – rage.

Anti-intellectualism is a ruling class reflex, whereby ruling class stupidity is attributed to the masses (I think we’ve discussed here before the ruse of the Thick Posh Person whereby make a show of pretending to be thick in order to conceal that they are, in fact, thick.) It’s scarcely surprising that inherited privilege tends to produce stupidity, since, if you do not need intelligence, why would you take the trouble to acquire it? Media dumbing down is the most banal kind of self-fulfilling prophecy.

As Simon Frith and Jon Savage long ago noted in their NLR essay, ‘The Intellectuals and the Mass Media’, which Owen recently brought to my attention again, the plain common-man pose of the typical public school and Oxbridge-educated media commentator) trades on the assumption that these commentators are far more in touch with ‘reality’ than anyone involved in Theory. The implicit opposition is between Media (as transparent window-on-the-world transmitter of good, solid commonsense) and Education (as out-of-touch disseminator of useless, elitist arcanery). Once, Media was a contested ground, in which the impulse to educate was in tension with the injunction to entertain. Now – and the indispensable Lawrence Miles is incisive on this, as on so many other things, in his latest compendium of insights – Old Media is almost totally given over to a vapid notion of Entertainment – and so, increasingly, is education.

In my teenage years, I certainly benefited far more from reading Morley and Penman and their progeny than from the middlebrow dreariness of much of my formal education. It’s because of them, and later Simon and Kodwo et al, that I became interested in Theory and bothered to pursue it in postgraduate study. It is essential to note that Morley and Penman were not just an ‘application’ of High Theory to Low Culture; the hierarchical structure was scrambled, not just inverted, and the use of Theory in this context was as much a challenge to the middle class assumptions of Continental Philosophy as it was to the anti-theoretical empiricism of mainstream British popular culture. But now that teaching is itself being pressed into becoming a service industry (delivering measurable outputs in the form of exam results) and teachers are required to be both child minders and entertainers, those working in the education system who still want to induce students into the complicated enjoyments that can be derived from going beyond the pleasure principle, from encountering something difficult, something that runs counter to one’s received assumptions, find themselves in an embattled minority. Here we are now entertain us.

The credos of ruling class anti-intellectualism that most Old Media professionals are forced to internalise are fare more effective than the Stasi ever was in generating a popular culture that is unprecedently monotonous . Put it this way: a situation in which Lawrence Miles languishes, at the limits of mental health, barely able to leave his house, while the likes of Rod Liddle swagger around the mediascape is not only aesthetically abhorrent, it is fundamentally unjust. Contrary to the ‘it’s only hedonic stim’ deflationary move that both Stekelmanites and Popists share, popular culture remains immensely important, even if it only serves an essential ideological function as the background noise of a capitalist realism which naturalises environmental depredation, mental health plague and sclerotic social conditions in which mobility between classes is lessening towards zero.

A class war is being waged, but only one side is fighting.

Choose your side. Choose your weapons.

K got mail

1. Wesley of Love and Terrorism contests some of Emmy Hennings' claims:

- I disagree with some elements of Emmy Henning's short account of Mark Latham as a character who the conservative government was frightened of. On the contrary the government successfully exploited Latham's resentment.

From the beginning of his leadership they knew that they could use it, and it's a significant reason why Latham's electoral performance was catastrophic for Labour in that that election ended in the government winning both houses of parliament. A famous television clip from his election expresses this. In it Latham emerges from a radio interview as his conservative opponent John Howard coincidentally waits outside the studio. Latham looms up to Howard very aggressively and overbearingly, while Howard stands smiling and indifferent to this aggression while the cameras lap it up. That expression of hot resentment versus cool indifference was indicative of the government's successful labeling of Latham as unpredictable and chauvinistic. In the end they were almost certainly correct. I think there can be a practical purpose for contexts in which individuals can understand their own class history because that's often necessary to transforming it, but politics will always be a world of means and ends in which the influences of personal histories are almost always rightfully marked as irresponsible.

This obviously connects with the 'chip on the shoulder' thing, the condemnation of which smugly assumes that working class people should be grateful for admission into the ruling class world rather than furious that they were excluded, and that so many others continue to be exploded.

2. Bat points out that Nina Simone's 'Sinnerman' 'is also the closing credits song to the recently released (and in my view sorely underrated) film Golden Door'.

August 09, 2007

Oh Timbaland

(being, amongst other things, a belated billet-doux to Future sex/ Love Sounds)

|  |  |

If Rihanna is the Queen of Pop, then Timbaland is now restored to his rightful place as King. The fact that Rihanna has finally been displaced from the UK number 1 slot by Timbaland's 'The Way I Are' means that we have had the best succession of number 1s since...who knows when. It's hard not to read Timbaland's continuing pre-eminence as a symptom that things are moribund elsewhere (where are all the young turks gunning for his crown?), but Timbaland is a moving target, and today's Tim is not at all the same beast as Timbaland 97.

Three years ago, Timbaland looked as if he was idling into irrelevance. It's significant that his reinvention went via Nelly Furtado and Justin Timberlake: no-one can doubt any more that he is a pop - rather than an r and b or hip hop - producer. Timbaland's productions may no longer so ostentatiously advertise their weird geometries, but they have acquired a slow burn subtlety. It took me a while to acclimatize to the new Timbaland. I found the unconsummated cocaine buzz of 'SexyBack' immediately addictive because it gave me what I expected and wanted from Timbaland: a Foxxoid EBM slink over which Tim presided as some psychotic mis-director, inviting JT to take us to a chorus that would never come, the song looping back to the verse from an Escheresque bridge that led nowhere. Initially, however, I had made the lazy mistake of dismissing the rest of Future Sex/ Love Sounds as a series of formally conservative, if superior, ballads, Timbaland sacrificing his avant-edge to the requirements of the ballad form. But, a year too late, and I'm practically obsessed with the LP, and what I most value in Timbaland's current incarnation is his luxurious refurbishment and modernization of the Ballad.

Future Sex now strikes me as a sumptuous neo-disco noo-wop song suite lent a space-station sheen by Timbaland's epic production.

Voyou - who wasn't nearly so slow off the mark as me in swooning for Future Sex's charms - intriguingly described the LP as queering of r and b. But part of what interests me about the LP is the way that it re-invents r and b heterosexuality from the male point of view. It's as if Timberlake has sought to rise to the demands made by pop's female desiring-machine in the last decade - can this baby boy keep up? If Justin is still too (baby) boyish to entirely convince as the man ‘on a mission to please' of the title track, it is at least heartening that the song is orientated towards female gratification.

The obvious precursor for Future Sex/ Love Sounds would be Prince – who can miss the echoes of Lovesexy in the title? - but, for my money, Future Sex outdoes anything that revolting priapic spiv ever achieved. Timberlake has a capacity to dissolve into the sound, to melt into multi-tracked falsetto, to coo and croon, that I’ve never found in the preening Prince, even though his supporters always attribute such lovestruck ego-dissolution to him. (A better comparison for the Timberlake of Future Sex might be Blackstreet, who at their best rendered male desire in terms of a blissful disabling.)

The characteristics of JT that made me have misgivings around the time of Justified - a certain blankness, a desire to please standing in for charisma - have now become virtues. On Justified neither Timbaland nor the Neptunes came up with a sonic design sufficiently unique to dispel the impression that Timberlake was a boyband refugee become Michael Jackson wannabe. But Timberlake's ingenuousness is now the perfect complement to Timbaland's ingenuity, and the two appear to be influencing one another. (One other product of this collaboration is the love-hangover ballad 'Rehab' on the new Rihanna album, which Timberlake co-wrote and sang backing vocals on, and Timbaland produced.) Set a challenge by Timberlake, Timbaland hasn’t given up his freaky-freaky weirdness so much as secreted it in the crevices and secret passages of the Ballad. Throughout the LP, Timbaland renders the non-relation between the sexes as an SF encounter, a bride-stripped bare conjoining of sounds that are suppurating-wet and Dali-desert dry, spine-crackingly hard and yieldingly soft. The production is all about the detail, a masterpiece of feints and faint traces, echoes and nuances (check, for instance, the slight nod to the ‘Good Times’ bassline on ‘Future Sex/ Love Sounds’, Timbaland repositioning himself in a disco lineage).

Future Sex/ Love Sounds is a love-song suite that aims to compete with the very best. If Junior Boys' So this is Goodbye was 06's No One Cares, then Future Sex was its Songs for Swingin' Lovers. (Greenspan and Timberlake, two synthetic disco Sinatras, with 21st century pharmaceuticals - or their sonic analogues - substituting for Frank's martinis and whisky sours). Songs for Ravin' Lovers, perhaps, with Timbaland's magisterial arrangements - or derangements - plugging the Ballad into all the rushes, tics and washes in his post-Rave box of tricks.

As far as I'm aware, Timbaland has always denied that his production was directly influenced by the hardcore continuum, and in many ways it's more interesting if he arrived at a similar abstract machine to Rave and its progeny by an entirely different route. Voyou brilliantly characterised Future Sex's 'My Love' as 'weird ghost-rave (but not at all hauntological; more hammer horror, or Scooby Doo)', a description so perfect that every time I hear the track now I'm unable to shake the image of an animated Justin being chased by white-sheeted cartoon ghosts, the inhuman gibbering and piping FX recalling some electro-ghoul from an 80s videogame. 'My Love' turns the commonplace of E as a luv'd up drug on its head, making the delirial exhilaration of falling in love sound like an E-rush, with a breathless JT - gabbling as if he has popped ten pills to many - fast forwarding through a virtual slideshow of anticipated future-love vignettes ('I can see us holding hands/walking on the beach, our toes in the sand/ I can see us on the countryside/ sitting on the grass, laying side by side').

Timberlake is at his best as the lover beguiled, betrayed and stoned by the object a, and what impresses is about Timbaland’s sympathetic-but-estranging production is how it situates JT in – or rather distributes him across – soundscapes that both complement and complicate the yearning, bliss and aches of the lover’s discourse. On the bittersweet sunset-fading-into-gloom of 'Summer Love', it's like Timberlake is trying to hold onto love as it begins to drain away before it has properly begun, the maudlin stomp of the rhythm track underscoring the edge of desperation beneath the lyric's superficial optimisim ('this just can't be summer love').

With 'What Goes Around', we are beyond the end of the affair - and beyond the pleasure principle. The song sees Timberlake lording it on the moral high ground, enjoying the just-deserts scenario of his betrayer herself being betrayed. Recrimination has replaced anticipation, and the stalled sitar loop and cycling love-comedown strings join with the abandoned Timberlake in mocking his ex-lover's misery. Yet the amount of seething, sadistic jouissance that Timberlake derives from the situation (‘You spend your nights alone/ And he never comes home/And every time you call him/ All you get's a busy tone/ I heard you found out/ That he's doing to you/ What you did to me') suggests that he is still in the grip of a love that is no longer alive but cannot die. By the time of the closing interlude, we even begin to suspect that the song is some Singing Detective-style revenge fantasy, and that his former lover has not been rejected by her new love at all.

'Until the End of Time' makes the oldest of pledges to the lover – the cocoon of her embrace will be enough to protect JT from the slings and arrows of an indifferent universe – but Timbaland gives it the widescreen treatment, and you feel as if you are surveying the cosmos from the bridge of a spaceship. The strings swirl like the milky way, while a massive Tommy Boy/ Leblanc-style snare pounds like a solar flare, spectacular and ominious.

Timbaland’s own solo LP from this year, Shock Value cannot compare with Future Sex. By contrast with the languid consistency of Future Sex - which, like So This is Goodbye, is an album that could only exist in the digital era - Shock Value suffers from a blight that afflicts so many CD albums. The plethora of tracks inevitably give it a piecemeal feel , an effect further amplified by an eclecticism that makes it difficult to digest (as a) whole. But there are plenty of jewels among the fragments, for instance:

‘Time’, guesting Goth-devivalists She Wants Revenge (who’d have thought that there would be a band influenced by the Danse Society in 2007?), which sounds like a karaoke Ian Curtis over a channelling of ‘She’s Lost Control’.

‘2 Man Show', featuring Elton John on piano, the soundtrack to some impossibly lavish faux-baroque masque, which puts me in mind of the vogueing neo-New Romantic fops in Russell T Davies’ chic-anachronistic Casanova.

Most uncanny – or should that be weird - of all: ‘Oh Timbaland’ which digitally-doctors Nina Simone’s ‘Sinnerman’, so that, instead of singing ‘Oh sinnerman’, Simone appears to be saying ‘Oh Timbaland'. The track was famously used in the closing credits sequence of INLAND EMPIRE, so Timbaland’s use of it poses an enigma: is it just a weird coincidence, or did Timbaland sample ‘Sinnerman’ because he had seen the film? Either way, it’s fascinating, another example of Tim’s keeping it strange.

August 07, 2007

Correspondence

The excellent Emmy Hennings with another moving contribution to the class discussion:

- I've been following with great interest your recent posts on class. So often, I wish for debates and commentary of an equal calibre here where I live, but in Australia class - or, to be specific, class envy, hatred and resentment - is one of the great unmentionables. Only witness the fate of Mark Latham, former Leader of the Opposition (Australian Labor Party), whose reign was swift and whose downfall was spectacular. Though he was in many ways an odious right-wing headkicker, his council house upbringing and general air of grim determination ( I'm gonna get my revenge on these fuckers) was enough to terrify the Government, established media, etc. Especially when he started talking about taking money away from private schools and giving it back to public schools. (Eleven years of financial perfidy by the Liberal Party has resulted in the majority of Federal funding for education going to already wealthy private schools; they often get millions of dollars per year while public schools are still waiting for toilet blocks).

But before I get completely sidetracked...

What I have wished for - and maybe this applies more to an Australian context than to a British one, because I do get the sense that class mobility in Australia is more common an experience than in Britain - is some nuance in discussing matters of class, particularly as they relate to personal experience. And you have done this so well, and people have responded to it. For ages I've thought that my own talk of feeling between classes was just self-indulgent waffle, but it's true, as an experience - true for myself and many others.

My family is a mixture of teachers and tradespeople - builders, electricians, etc. I suppose the label would be lower-middle class (though I often wonder if this nebulous category of the lower-middle has much worth, whether it would not be better to speak of a broader working class and, at the bottom of the social hierarchy, an underclass created by capital's need for structural unemployment?) Both my parents (of the same generation as Mark Latham, interestingly enough: born in the late 50s/early 60s, the fag end of the baby boomers) were brought up in council housing; my dad went to university on the long-abandoned Commonwealth Scholarship system and my mum, a few years later, to Teachers' College, in the brief window during the 1970s when higher education was made free in this country. They were married at nineteen and divorced by twenty-eight, when I was five years old. I remember my childhood as a jumble of cheap rental houses, living with my grandparents, mismatching school uniforms worn from one school to another, etc etc. There was real poverty. My brother was only a baby and my mum, bringing us up, unable to afford childcare, stopped teaching and had a number of part-time jobs - bar person, hotel cleaner - before eventually she put herself through university (a Graduate Dip.Ed) on the single parent pension, and went back to teaching. I remember falling asleep as a child to the sound of her typewriter banging away into the night, writing her uni assignments after she had put us to bed.

When your parents are themselves educators, the discursive continuity between school and home reaches comic proportions - we frequently had to remind my mother that she was using her "teacher" voice on us again...

I can certainly relate to this experience; I can also appreciate the flipside: when your parent or parents are themselves teachers you see teaching for what it is - a job - and not a position of strange mystery (how many of my friends at primary school were convinced that teachers slept in the school overnight, that they simply appeared each day!). There's a continuity but also a discontinuity between an experience of school and home as, a child of teachers, you witness the 'hidden' labour of teaching: the hours and hours of unpaid overtime, assignment marking, report writing, etc.

So, where do I fit, with parents who are teachers but who were often poor? (And my father was barely in the picture here; I was raised by a single parent). Who never forgot their own class resentment or origins? (One of the compulsory aspects of class mobility, so it seems, is forgetting or suppressing where you came from, "moving on", and maybe the anxiety of feeling between classes is partly an inability or unwillingness to do this?). Where do I fit, when those who've been through higher education are still an absolute minority in my extended family, where 'security' - financial, employment - is by no means a guarantee? (It occurs to me that the class confidence you write so observantly of is absolutely tied to this sense of security, that "everything will be alright"). And especially, where do I fit in a society where radical politics is so often seen as some self-indulgent pastime of the bourgeoisie when my own family are proud and articulate about their radical, working class history? My great-grandparents were railway workers and Communists. My grandfather, a crane driver, was a staunch trade unionist. My parents marched against the Vietnam war in their mid-teens. My mother reads Brecht and my father reads Chomsky. My family have passed on this sense of historical awareness to me - it has been one of their greatest gifts.

Meanwhile, in connection with Eltham Palace, Ben Noys sends this quotation from Geoffrey Hill's Collected Poems (Penguin 1985)

- Funeral Music: An Essay

In this sequence [referring to the poem 'Funeral Music'] I was attempting a florid grim music broken by grunts and shrieks. Ian Nairn's description of Eltham Palace as 'a perfect example of the ornate heartlessness of much mid-fifteenth-century architecture, especially court architecture' [Ian Nairn, Nairn's London (1966), p.208] is pertinent, though I did not read Nairn until after the sequence had been completed.