February 28, 2007

Rumbles, grumbles

My review of the very generic new Fall LP is now up on the Fact website.

Sadly, Carl was right...

Ecclesiastical nihilism

Reader Matthew Jones joins in the discussion of Metal/hauntology/Burial:

- Two points on Alex's recent thoughts:

1) As he quite rightly points out, sonically Sunn-O are removed from much of metal, but he should also have noted the affect it has on the listener in an emotional/spiritual sense, particularly when experienced live. The ceremonial nature of their performance is actually, unlike the relentless grind of every other doom metal act (e.g Khanate, recent Celtic Frost material) that I've ever heard, an uplifting and joyous experience; a total embracing of the darkness they (largely wordlessly) articulate, without the aggression and violence that characterises their peers.

In many ways, Sunn-O's closet relatives are not within metal, but in spiritual/religious music, such as qawili. Compare and contrast Sunn-O with Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan; lengthy pieces of music (where something clocking in at about 10 minutes could be considered brief), which cycle through seemingly endless repetitions, leaving the listener either in a total tranced-out state or sending them into a state of pure rapture (if you ever see Sunn-O live, take a few moments to cast yr eye around the audience and you'll see what I mean.) In the case of Nusrat, he frequently dispensed with actual words and uses a series of vocal sounds that in many ways express the intense religious love/ecstasy far better than words ever could (even if one does understand Urdu); Sunn-O's vocals, when they are present, are so ridiculously distorted and echo-plexed that even when they sound like words you couldn't possibly make out more than the briefest of snippets (and like Nusrat, would probably weaken the effect). Both artists share the ability to command yr attention without leaving you the actual choice of where to direct it; yr drawn in to their world inexorably; compare that to other doom metallers, where unless you are really on it trying to pay attention becomes something of a chore fairly quickly.

Sunn-O's sound, and fundamentally their philosophy, is one of ecclesiastical nihilism. It goes deeper than"revelling in the jouissance of the terminal" (the words 'revel' and 'jouissance' themselves suggest a level of indulgence and frivolity absent in their sound), but to some sort of religious ecstasy induced through distortion and sub bass. And it is PURE, in a way their peers could never hope to be. Anderson and O'Malley don't refer to their live shows as "sub-sonic rituals" and didn't call the last tour "autumnal bass communion" for nothing.

2) On the subject of Burial, it surprises me that no one has linked his post-rave south London with Joy Division's Manchester as etched out in "Unknown Pleasures", [k-punk interjection. They have - Jon Wozencroft was also very quick to insist on the parallel...] which to my ears sounds like it should immediately be added to the hauntological canon (if such a thing really exists).

Sonic superficiliaties such as minimalism, echoes and found sounds in the mix? Check. A sense of mourning infusing both records? Check ("Me and him, we're from different, ancient tribes, now... we're both almost extinct... dreams don't rise up they descend/ but I remember/ when we were young."). Temporal disturbances? Check. (Joy Division and Hanett's gutting+spectralising of rock* tunes, e.g war pigs, maps almost perfectly onto Burial's faded 2-step beats and rave synths. Not to mention Wilderness' "I travelled far and wide through many different times" line, which in many ways strikes me now as UP's key lyric; the isolation and despair expressed by Ian Curtis stemming from knowing that which others do not remember and cannot know).

Both records create seemingly accurate yet entirely mythical representations of the areas most closely associated with the two artists; a kind of map to orientate yrself with if you've no previous knowledge of the area, which you'll find shows landmarks that no longer exist upon arrival; just rubble, boarded up windows and flyers from over a decade ago peeling of the walls. Also, they are both associated with scenes (post-punk and dubstep) that they both still seem so far removed from; even the core proto goth groups like The Cure and The Banshees don't really fit neatly with JD; whereas they sound tortured but alive, JD and in particular Ian Curtis (as you've noted before) already sound dead, and Burial clearly operates in a different space to his dubstep peers, as previously discussed by pretty much everyone who has voiced an opinion on the subject. Perhaps the strongest link between JD and Burial is this sense of being alone, falling through the little gaps and cracks in time into a place where they've always been and always will be, totally separate from their contemporaries and their successors (I imagine that like Joy Division no one will be able to go anywhere near Burial's musical terrain, both sounding like the aural equivalent of those little time capsule things with artifacts of today's world that get buried for school projects and such like; despite being reflections on the past, they've also exhausted the final alternatives for their particular musical format).

* Kevin Shields described MBV's sound as rock minus its guts, "the remnants". Whilst I've never been convinced about this as a description of MBV, I can't imagine a better description of JD exists.

Matthew's remarks serve as the perfect riposte to Simon's scepticism as to whether 'Sunn O))) have really escaped the irony/standing-slightly-outside-what-they-do syndrome'. When I saw Sunn O))) last year, there was absolutely no sense of irony, and much of the crowd was, as Matthew says, enraptured, entranced. Of course, I found it difficult to fully submit to the group, to take them at (po)face value, but I had to recognize that this was my problem, my sceptical 'good sense' insisting that 'surely they cannot be serious...' Any ceremony looks ridiculous to those not properly initiated (which is why I've always thought that snorting about the absurdity and silliness of the ritual sex scenes in Eyes Wide Shut entirely missed the point). (It could be that Sunn O))) are like Laibach, and that the irony consists precisely in their very straight-faced identification with their role...)

I find Simon's comparisons of Sunn O))) with KLF and intelligent drum and bass unconvincing. Surely grinning ape japesters and arch-scamsters KLF were PoMo incarnate, PoMo in excelsis in fact, and their robe-wearing was nothing else but an empty citation rather a serious attempt to be the impersonal focus of a ritual. The supposed 'intelligence' of intelligent drum and bass, meanwhile, was achieved by downplaying rave's 'silliness'; Sunn O))), by contrast, amp up metal's absurdities. It is as if they want to produce a sound that will finally match the ridiculous excesses of metal's rhetoric and imagery. And whereas intelligent drum and bass suppressed jungle's impersonal intensities by introducing tasteful Weather Report-ish musical affectations, Sunn O))) move in exactly the opposite direction, subtracting metal's residual rock and roll dynamics and sonic pallette in favour of an exploration of forbiddingly featureless anti-climactic drone-plateaus. (That is why the comparison with Loop does strike a chord; when I first heard Sunn O))), the reference point I reached for was Loop.)

Another parallel with Dubstep springs to mind at this point. Both are about the significance of the minimal difference. Sunn O)))'s portentous repetitions slow down your nervous system so that a single chord change becomes a moment of enormous drama. (In this respect, they couldn't be further from Trad Metal, which aims to vacuum pack as much baroque detail into every second of sound.)

The devotional aspect of Sunn O)))'s sound raises interesting questions. Like Dubstep, Sunn O))) live are lullling, enwombing, rather than oppressive. (Almost the reverse of MBV who, could reputedly be a violent and visceral live.) But then again, Xasthur are curiously calming, too, if you play them at an ambient volume. (The lack of tension-release, the swampy viscosity, make Xasthur excellent background music, really good to work to.) Which poses the question: how much of Xasthur's nihilism comes from the sound, and how much from the words - or more precisely (since the lyrics are all but inaudible), the titles?

February 25, 2007

Po-faced versus PoMo

Reader Alex Williams on metal and hauntology:

- Structurally the real black metal hauntologists/doom-gazers are Sunn0))), their last album (Black one)liberally quoting (but in almost unrecognizable, expanded forms) classic black metal riffs, their live show almost a crystallization of the ghost of metal (in its most evil/ceremonial forms and equally its camp ludicrousness)... but a metal reduced, boiled down, vaporised in some hellish longhair's bong - a single gesture remaining, (a raised satanic salute, as a guitar chord drones on and on...) Whilst they have begun to quote from black metal (whose hallmark is tinny atmosphere, and in its modern non-fascist form depressive nihilism let us remember) the form remains distinctly that of doom metal (hallmark: massive tritone drone) but again a doom metal divested of its "rockingness" (i.e. - rhythm and blues, percussion, climax) and purified into a form which has almost nothing to do with metal at all, for all its signifiers and quotations... but at the same time, whilst in some respects it works in a similar fashion to Burial, the analogy fails because even as it is a sonic ghost-image of metal, (nothing but reverberating amp hum and ritualistic imagery remains) it is not an elegy (is an elegy even possible in the culture of metal - the genre itself kept in eternal forward aesthetic motion so nothing to mourn, alive, yet death/doom fixated - indeed revelling in jouissance, as you say, at the terminal?)

In that case, Black Metal could be lined up more with what we might call the 'mainstream' of Dubstep (with which Burial has very little in common). Dubstep's relationship to jungle doubles Sunn0))'s relationship to Metal. Like Sunn0))), Dubstep has produced a non-elegiac 'ghost-image' of its source-inspiration (which in the case of Dubstep is Jungle). At one level, Dubstep and Sunn0))) could be heard as a (literal) continuation of their inspirations: a sound constructed entirely out of a distending of the after-effects, the traces (echoes, reverberations) of a departed sonic body.

What Metal and Dubstep (and Noise, for the matter) have in common is a philosophy, a metaphysics. At one step back, what they share is a commitment to the idea that music should come out of a philosophy. What is absolutely refused is the hegemonic Indie-endorsed ratification of commonsense, with its - usually implicit - insistence on the smallness of music, its ultimate irrelevance. Irony is repudiated. Music is not 'just music'. It to be taken extremely seriously, even at the risk of seeming absurd. It is perhaps the absence of any fear of ridicule that is most to be treasured in (Doom and Black) Metal. Xasthur's nihilism, which bleeds out through all their titles ('Arcane and Misanthropic Projection', 'Through A Trance Of Despondency') is unrelenting, unrelieved by any raised eyebrows, while Sunn0)))'s return to costume and performance in the most po-faced, ritualistic sense are a repudiation of the dressed-down Indie assertion of an continuity between everyday life and the stage.

If you want to hear the Metal/Dubstep, parallels, the Distance/Vex'd Breezeblock mix (available to download here) is well worth a listen.

February 22, 2007

Links and thoughts

1. Ha ha

2. Wolves Evolve takes up and runs with the Robbie thing. (My quoting of Liam Gallagher, naturally, shouldn't be taken as any kind of endorsement of Oasis, perish the thought. But Gallagher has a sledgehammer way with invective, and his relentless pillorying of Robbie is certainly to his credit.

3. A tremendous run of posts by Dominic on Xasthur/ black metal/ generic misanthropy, partly in dialogue with Documents. Fascinating as Documents' take on Xasthur-as-metal-hauntology is, I'm inclined to agree with Dominic that Xasthur are better described as 'Doomgazer'. Xasthur are like Loveless-era My Bloody Valentine with all the oestrogen removed - nihilism as jouissance. As Dominic suggests, there is no temporal discrepancy in Xasthur. Xasthur may have 'blackened buzz ... wrapped in huge swaths of fuzzy sonic fog' but their textures aren't slices of time, if only because time has ended in their run-down cosmos: 'Black metal is relentlessly entropic, committed to a one-way temporality in which intensities run inexorably down to zero and stay there, forever'. It is like the fantasy of being present at your own funeral, but on a much grander, more epic, scale. 'The state of mind suggested by Subliminal Genocide is one of trancelike contemplation of the ashes of the cosmos - the logical end-point of Xasthur’s misanthropic individualism.' Dominic argue that Xasthur's 'is a universe of perpetual suspension, in which resolution can never arrive' but it might almost be the reverse: a universe in which resolution has been finally achieved, and the tension that accompanies all vital processes - or rather, the tension that is all vital processes - has been extinguished. Death, but no death drive.

4. I'm glad that Simon drew my attention to You need a Mess of Help. Who could resist a site whose links bar includes the following: Entrances To Hell, Sub-Urban, Derelict Places, Nobody There, Subterranea Britannica, UK Cold War, Kelvedon Hatch, English Heretic, Geograph British Isles, Haunted TV, Delia Derbyshire, TV ARK, British Horror Films, Quatermass, Outpost Gallifrey? I found myself nodding along to this post on Boards of Canada. I must admit, until recently I wasn't able to see the appeal of BoC at all, and that was largely because of the indifferent beats. I also agreed with pretty much all of this. (I say pretty much, because Mess is nowhere near hard enough on Love & Monsters, which was the worst. Dr. Who. eva.)

February 19, 2007

Weird Realism

Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Theory

26th April 2007, 11a.m. – 6 p.m.

Centre for Cultural Studies

Goldsmiths University

London

'A philosophy should be judged on what it can tell us about Lovecraft...' (Graham Harman)

A unique one-day symposium dedicated to exploring H. P. Lovecraft’s relationship to Theory.

The event will not follow the ordinary format of the academic conference. Some written materials will be circulated beforehand, but there will be no papers delivered on the day. Instead, there will be structured discussions based on five of Lovecraft’s stories:

· ‘Call of Cthulhu’

· ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’

· ‘The Dunwich Horror’

· ‘The Shadow out of Time’

· ‘Through the Gates of the Silver Key’

Themes to be discussed include:

· The Weird

· Fictional systems

· Lovecraft’s pulp modernism

· Houellebecq’s Lovecraft

· Lovecraft and hyperstition

· Lovecraft’s materialism

· Lovecraft’s racism and ‘reactionary modernism’

· Lovecraft and schizophrenia

· Lovecraft and the transcendental

· Lovecraft and schizophonia

Participants so far include:

Benjamin Noys (Chichester) – author of The Culture of Death and Georges Bataille: A Critical Introduction

Graham Harman (Cairo) – author of Tool Being and Guerilla Metaphysics.

China Miéville – acclaimed author of Perdido Street Station, The Scar, and other tales of the Fantastic.

Luciana Parisi (Goldsmiths) – author of Abstract Sex: Philosophy, Biotechnology and the Mutations of Desire

Steve ‘Kode9’ Goodman (UEL) – author of the forthcoming Sonic Warfare

Dominic Fox – Poetix weblog

Mark Fisher (Goldsmiths) – k-punk weblog

Anyone wishing to attend should email Mark Fisher (k_punk99[at]hotmail.com). Registration is free but places are limited. If anyone wishes to lead discussion on any of the stories, please state in the email which story you would like to talk about.

February 17, 2007

Postmodernism as pathology, part II

|  |

The thing is, Robbie, there's no rehabilitation from PoMo.

The sickness that afflicts Robbie Williams is nothing less than postmodernity itself. Look at Williams: his whole body is afflicted with reflexive tics, an ego-armoury of grimaces, gurns and grins designed to disavow any action even as he performs it. He is the 'as if' Pop Star - he dances as if he is dancing, he emotes as if he is emoting, at all times scrupulously signalling - with perpetually raised eyebrows - that he doesn't mean it, it's just an act. He wants to be loved for 'Rudebox' but, unfortunately for him, his audience demands the mawkish sentimentality of 'Angels'. How Robbie must hate that song now, with its humbling reminders of dependency (Williams' career went into the stratosphere on the basis of 'Angels') and lost success...

Let me entertain you, let me lead you

There's surely a Robin Carmody-type analysis to be done of the parallels between Williams and Tony Blair. Williams' first album, the tellingly-titled Life Thru a Lens was released in 1997, the year of Blair's first election victory. There followed for both a period of success so total that it must have confirmed their most extravagant fantasies of omnipotence (Blair unassailable at two elections; Williams winning more Brit awards than any other artist). Then, a decade after their first success, an ingominious decline into irrelevance (the post-Iraq Blair limping out of office as a lame-duck leader, Williams releasing a disastrous album and checking himself into rehab on the day before this year Brit awards, at which he had received a derisory single nomination). Of course, there are limits to the analogy: Blair is popular in the States, whereas Robbie...

Williams and Blair are two sides of one Joker Hysterical face: two cracked actors, one given over to the performance of sincerity, the other dedicated to the performance of irony. But both, fundamentally, actors - actors to the core, to the extent that they resemble PKD simulacra, shells and masks to which one cannot convincingly attribute any inner life. Blair and Williams seem to exist only for the gaze of the other. That is why it is impossible to imagine either enduring private doubts or misgivings, or indeed experiencing any emotion whose expression is not contrived to produce a response from the other. As is well known, Blair's total identification with his publicly-projected messianic persona instantly transforms any putatively private emotion into a PR gesture; this is the spincerity effect (even if he really means what he is saying, the utterance becomes fake by dint of its public context). The image of Blair or Williams alone in a room, decomissioned androids contemplating their final rejection by a public which once adored them, is genuinely creepy.

It is perfectly possible to imagine Robbie exhibiting public doubts, of course - indeed, as his former reflexive potency declines into reflexive impotence, he is most likely to be seen insisting upon his inadequacy and failure. No doubt this is why Williams' announcement of his 'addiction' to anti-depressants and caffeine has been greeted with a certain scepticism (suspicion has been aroused in part because of the timing of the announcement, on the eve of the Brits). But this scepticism misses the point. Williams' sickness is, precisely, his incapacity to do or experience anything unless it provokes the attention of the other.

Or: as Liam Gallagher more succinctly put it, in words worthy of Mr Agreeable at his compassionate best:

"If you've got a fucking problem, why do you want the whole world to know about it?.

I say sort yourself out. You make a fucking crap album then want everyone to feel sorry for you.

What a fucking tosser.”

February 16, 2007

Memorex for the Krakens: The Fall's Pulp Modernism, part III

Don’t start improvising for Christ’s sake

The temptation, when writing about The Fall’s work of this period, is to too quickly render it tractable. I note this by way of a disclaimer and a confession, since I am of course as liable to fall prey to this temptation as any other commentator. To confidently describe songs as if they were ‘about’ settled subjects or to attribute to them a determinate aim or orientation (typically, a satirical purpose) will always be inadequate to the vertiginous experience of the songs and the distinctive jouissance provoked by listening to them. This enjoyment involves a frustration – a frustration, precisely, of our attempts to make sense of the songs. Yet this jouissance – something also provoked by the late Joyce, Pynchon and Burroughs - is an irreducible dimension of The Fall’s modernist poetics. If it is impossible to make sense of the songs, it is also impossible to stop making sense of them – or at least to it is impossible to stop attempting to make sense of them. On the one hand, there is no possibility of dismissing the songs as Nonsense; they are not gibberish or disconnected strings of non sequiturs. On the other hand, any attempt to constitute the songs as settled carriers of meaning runs aground on their incompleteness and inconsistency.

The principal way in which the songs were recuperated was via the charismatic persona Smith established in interviews. Although Smith scrupulously refused to either corroborate or reject any interpretations of his songs, invoking this extra-textual persona, notorious for its strong views and its sardonic but at least legible humour, allowed listeners and commentators to contain, even dissipate, the strangeness of the songs themselves.

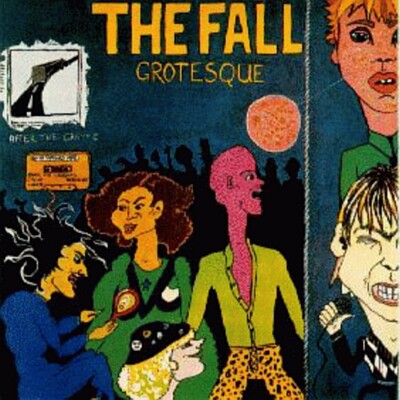

The temptation to use Smith’s persona as a key to the songs was especially pressing because all pretence of democracy in the group has long since disappeared. By the time of Grotesque, it was clear that Smith was as much of an autocrat as James Brown, the band the zombie slaves of his vision. He is the shaman-author, the group the producers of a delirium-inducing repetition from which all spontaneity must be ruthlessly purged. ‘Don’t start improvising for Christ’s sake,’ goes a line on Slates, the 10” EP follow-up to Grotesque, echoing his chastisement of the band for ‘showing off’ on the live LP Totale’s Turns.

Slates’ ‘Prole Art Threat’ turned Smith’s persona, reputation and image into an enigma and a conspiracy. The song is a complex, ultimately unreadable, play on the idea of Smith as ‘working class’ spokesman. The ‘Theat’ is posed as much to other representations of the proletarian pop culture (which at its best meant The Jam and at its worst meant the more thuggish Oi!) as it is against the ruling class as such. The ‘art’ of The Fall’s pulp modernism – their intractability and difficulty – is counterposed to the misleading ingenuousness of Social Realism.

The Fall’s intuition was that social relations could not be understood in the ‘demystified’ terms of empirical observation (the ‘housing figures’ and ‘sociological memory’ later ridiculed on ‘The Man whose Head Expanded’). Social power depends upon ‘hexes’: restricted linguistic, gestural and behavioural codes which produce a sense of inferiority and enforce class destiny. ‘What chance have you got against a tie and a crest?’, Weller demanded on ‘Eton Rifles’, and it was as if The Fall took the power of such symbols and sigils very literally, understanding the social field as a series of curses which have to be sent back to those who had issued them.

The pulp format on ‘Prole Art Threat’ is Spy fiction, its scenario resembling Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy re-done as a tale of class cultural espionage, but then compressed and cut up so that characters and contexts are even more perplexing than they were even in Le Carre’s already oblique narrative. We are in a labyrinthine world of bluff and counter-bluff – a perfect analogue for Smith’s own elusive, allusive textual strategies. The text is presented to us as a transcript of surveillance tapes, complete with ellipses where the transmission is supposedly scrambled.

- GENT IN SAFE-HOUSE: Get out the pink press threat file

and Brrrptzzap* the subject. (* = scrambled) .

‘Prole Art Threat’ seems to be a satire, yet it is a blank satire, a satire without any clear object. If there is a point, it is precisely to disrupt any ‘centripetal’ effort to establish fixed identities and meanings. Those centripetal forces are represented by the ‘Middle Mass’ (‘vulturous in the aftermath’) and ‘the Victorian vampiric’ culture of London itself, as excoriated in ‘Leave the Capitol’:

- The tables covered in beer/ Showbiz whines, minute detail/ It’s a hand on the shoulder in Leicester Square/ It’s vaudeville pub back room dusty pictures of white frocked girls and music teachers/ The bed’s too clean/ The water’s poison for the system/ Then you know in your brain/ LEAVE THE CAPITOL! / EXIT THIS ROMAN SHELL!

This horrifying vision of London as a Stepford city of drab conformity ('hotel maids smile in unison') ends with the unexpected arrival of Machen’s Great God Pan (last alluded to in The Fall’s very early ‘Second Dark Age’), presaging The Fall's return of the Weird.

The textual expectorations of Hex

- Hex press release: 'He'd been very close to becoming ex-funny man celebrity. He needed a good hour at the hexen school...'

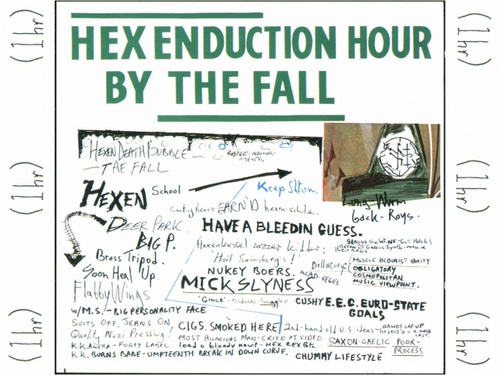

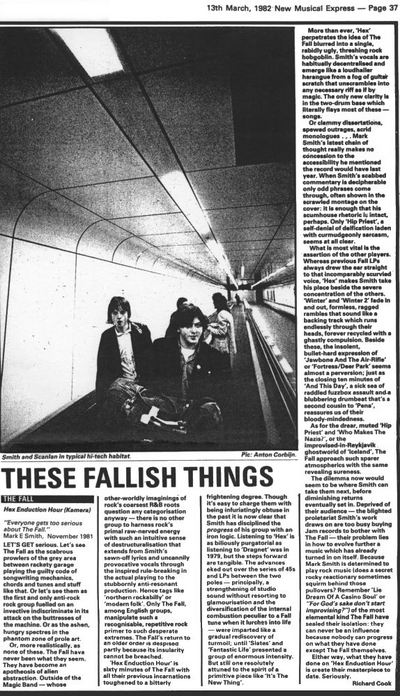

Hex Enduction Hour was even more expansive than Grotesque. Teeming with detail, gnomic yet hallucinogenically vivid, Hex was a series of pulp modernist pen portraits of England in 1982. The LP had all the hubristic ambition of Prog combined with an aggression whose ulcerated assault and battery outdid most of its postpunk peers in terms of sheer ferocity. Even the lumbering ‘Winter’ was driven by a brute urgency, so that, on Side One, only the quiet passages in the lugubrious ‘Hip Priest’ – like dub if it had been invented in drizzly motorway service stations rather than in recording studios in Jamaica – provided a respite from the violence.

Yet the violence was not a matter of force alone. Even when the record's dual-drummer attack is at its most poundingly vicious, the violence is formal as much as physical. Rock form is disassembled before our ears. It seems to keep time according to some system of spasms and lurches learned from Beefheart. Something like ‘Deer Park’ – a whistle-stop tour of London circa 82 sandblasted with ‘Sister Ray’-style white noise - screams and whines as if it is about to fall apart at any moment. The ‘bad production’ was nothing of the sort. The sound could be pulverisingly vivid at times: the moment when the bass and drums suddenly loom out of the miasma at the start of ‘Winter’ is breathtaking, and the double-drum tattoo on ‘Who Makes the Nazis?’ fairly leaps out of the speakers. This was the space rock of Can and Neu! smeared in the grime and mire of the quotidian, recalling the most striking image from The Quatermass Xperiment: a space rocket crashlanded into the roof of a suburban house.

In many ways, however, the most suggestive parallels come from black pop. The closest equivalents to the Smith of Hex would be the deranged despots of black sonic fiction: Lee Perry, Sun Ra and George Clinton, visionaries capable of constructing (and destroying) worlds in sound.

As ever, the album sleeve (so foreign to what were then the conventions of sleeve design that HMV would only stock it with its reverse side facing forward) was the perfect visual analogue for the contents. The sleeve was more than that, actually: its spidery scrabble of slogans, scrawled notes and photographs was a part of the album rather than a mere illustrative envelope in which it was contained.

With The Fall of this period, what Gerard Genette calls ‘paratexts’ – those liminal conventions, such as introductions, prefaces and blurbs, which mediate between the text and the reader – assume special significance. Smith’s paratexts were clues that posed as many puzzles as they solved; his notes and press releases were no more intelligible than the songs they were nominally supposed to explain. All paratexts occupy an ambivalent position, neither inside nor outside the text: Smith uses them to ensure that no definite boundary could be placed around the songs. Rather than being contained and defined by its sleeve, Hex haemorrhages through the cover.

It was clear that the songs weren’t complete in themselves, but part of a larger fictional system to which listeners were only ever granted partial access. ‘I used to write a lot of prose on and off,’ Smith would say later. ‘When we were doing Hex I was doing stories all the time and the songs were like the bits left over.’ Smith’s refusal to provide lyrics or to explain his songs was in part an attempt to ensure that they remained, in Barthes’ terms, writerly. (Barthes opposes such texts, which demand the active participation of the reader, to ‘readerly’ texts, which reduce the reader to the passive role of consumer of already-existing totalities.)

Before his words could be deciphered they had first of all to be heard, which was difficult enough, since Smith’s voice – often subject to what appeared to be loud hailer distortion - was always at least partially submerged in the mulch and maelstrom of Hex’s sound. In the days before the internet provided a repository of Smith’s lyrics (or fans’ best guesses at what the words were), it was easy to mis-hear lines for years.

Even when words could be heard, it was impossible to confidently assign them a meaning or an ontological ‘place’. Were they Smith’s own views, the thoughts of a character or merely stray semiotic signal? More importantly: how clearly could each of these levels be separated from one another? Hex’s textual expectorations were nothing so genteel as stream of consciousness: they seemed to be gobbets of linguistic detritus ejected direct from the mediatized unconscious, unfiltered by any sort of reflexive subjectivity. Advertising, tabloid headlines, slogans, pre-conscious chatter, overheard speech were masticated into dense schizoglossic tangles.

Who wants to be in a Hovis advert any way?

‘Who wants to be in a Hovis/ advert/ any way?’ Smith asks in ‘Just Step S’ways’, but this refusal of cosy provincial cliche (Hovis adverts were famous for their sentimentalised presentation of a bygone industrial North) is counteracted by the tacit recognition that the mediatized unconscious is structured like advertising. You might not want to live in an advert, but advertising dwells within you. Hex converts any linguistic content – whether it be polemic, internal dialogue, poetic insight – into the hectoring form of advertising copy or the screaming ellipsis of headline-speak. The titles of ‘Hip Priest’ and ‘Mere Pseud Mag Ed’, as urgent as fresh newsprint, bark out from some Voriticist front page of the mind.

As for advertising, consider ‘Just Step S’ways’’ opening call to arms: ‘When what you used to excite you does not/ like you’ve used up allow your allowance of experiences’. Is this an existentialist call for self re-invention disguised as advertising hucksterism, or the reverse? Or take the bilious opening track, ‘The Classical’. ‘The Classical’ appears to oppose the anodyne vacuity of advertising’s compulsory positivity (‘this new profile razor unit’) to ranting profanity (‘hey there fuckface!’) and the gross physicality of the body (‘stomach gassss’). But what of the line ‘I’ve never felt better in my life?’ Is this another advertising slogan or a statement of the character’s feelings?

It was perhaps the unplaceability of any of the utterances on Hex that allowed Smith to escape censure for the notorious line, ‘where are the obligatory niggers?’ in ‘The Classical’. Intent was unreadable. Everything sounded like a citation, embedded discourse, mention rather than use.

Smith returns to the Weird tale form on ‘Jawbone and the Air Rifle’. A poacher accidentally causes damage to a tomb, unearthing a jawbone which ‘carries the germ of a curse/ of the Broken Brothers Pentacle Church’. The song is a tissue of allusions - James (‘A Warning to the Curious’, ‘Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to you, my Lad’), Lovecraft (‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’), Hammer Horror, The Wicker Man - culminating in a psychedelic/ psychotic breakdown (complete with torch-wielding mob of villagers):

- He sees jawbones on the street/ advertisements become carnivores/ and roadworkers turn into jawbones/ and he has visions of islands, heavily covered in slime. / The villagers dance round pre-fabs/ and laugh through twisted mouths

‘Jawbone’ resembles nothing so much as a League of Gentlemen sketch, and The Fall have much more in common with the League of Gentlemen’s febrile carnival than with witless imitators such as Pavement. The co-existence of the laughable with that which is not laughable: a description that captures the essence of both The Fall and The League of Gentlemen's grotesque humour.

White Face finds roots

- Moorcock: Below, black scars winding through the snow showed the main roads. Great frozen rivers and snow-laden forest stretched in all directions. Ahead they could just see a range of old, old mountatins. It was perpetual evening at this time of year, and the further north they went, the darker it became. The white lands seemed uninhabited, and Jerry could easily see how the legends of trolls, Jotunheim, and the tragic gods - the dark, cold, bleak legends of the North - had come out of Scandinavia. It made him feel strange, even anachronistic, as if he had gone back from his own age to the Ice Age. The Final Programme

'Iceland', recorded in a lava-lined studio in Reykjavik , is a fantasmatic encounter with the fading myths of North European culture in the frozen territory from which they originated. ‘White face finds roots’ Smith’s sleeve-notes tell us. The song, hypnotic and undulating, meditative and mournful, recalls the bone-white steppes of Nico's The Marble Index in its arctic atmospherics. A keening wind (on a cassette recording made by Smith) whips through the track as Smith invites us to ‘cast the runes against your own soul’ (another James’ reference, this time to his ‘Casting the Runes’).

‘Iceland’ is rock as ragnarock, an anticipation (or is it a recapitulation) of the End Times in the terms of the Norse ‘Doom of the Gods’. It is a Twilight of the Idols for the retreating hobgoblins, cobolds and trolls of Europe’s receding Weird culture, a lament for the monstrosities and myths whose dying breaths it captures on tape:

- Witness the last of the god men ….

A Memorex for the Krakens

February 12, 2007

Hold on...

I'll be back midweek, with Part III of the Fall post featuring.... prole threat, textual expectoration, Hovis ads, ragnorock, white face finds roots...

Here's a sneak preview, in the MES font you can download here....

February 10, 2007

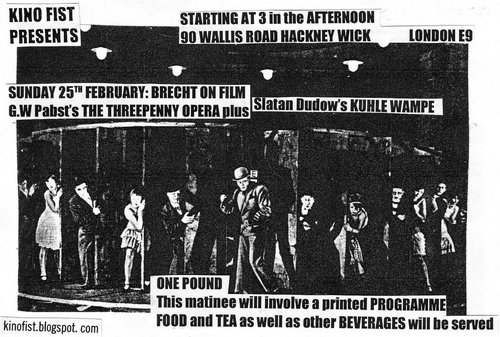

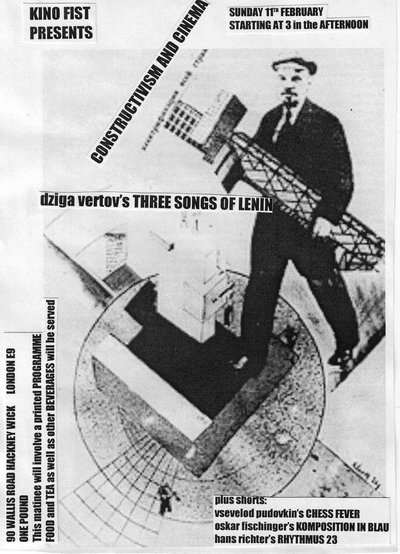

kino therapy

A reminder that the second Kino Fist presentation is taking place tomorrow (Sunday) at 3 PM in Hackney. Click on flyer for more details.

February 04, 2007

Memorex for the Krakens: The Fall's Pulp Modernism (part II)

(AT LAST - and they said it would not be done!: Part II - but - be warned - there is still a Part III to follow.) (Part I is here)

M R James, be born be born

- City Hobgoblins: 'Ten times my age, one tenth my height...'

- Mark Sinker: So he plunges into the Twilight World, and a political discourse framed in terms of witch-craft and demons. It's not hard to understand why, once you start considering it. The war that the Church and triumphant Reason waged on a scatter of wise-women and midwives, lingering practitioners of folk-knowledge, has provided a powerful popular image for a huge struggle for political and intellectual dominance, as first Catholics and later Puritans invoked a rise in devil-worship to rubbish their opponents. The ghost-writer and antiquarian M.R. James (one of the writers Smith appears to have lived on during his peculiar drugged adolescence) transformed the folk-memory into a bitter class-struggle between established science and law, and the erratic, vengeful, relentless undead world of wronged spirits, cheated of property or voice, or the simple dignity of being believed in.' 'Watching the City Hobgoblins', The Wire, August 1986

Whether Smith first came to James via TV or some other route, James’ stories exerted a powerful and persistent influence on his writing. Lovecraft, an enthusiastic admirer of James' stories to the degree that he borrowed their structure (scholar/ researcher steeped in empiricist common sense is gradually driven insane by contact with an abyssal alterity) understood very well what was novel in James' tales. ‘In inventing a new type of ghost,’ Lovecraft wrote of James, ‘he departed considerably from the conventional Gothic traditions; for where the older stock ghosts were pale and stately, and apprehended chiefly through the sense of sight, the average James ghost is lean, dwarfish and hairy – a sluggish, hellish night-abomination midway betwixt beast and man – and usually touched before it is seen.’ Some would question whether these dwarven figures ('ten times my age, one tenth my height') could be described as ‘ghosts’ at all; often, it seemed that James was writing demon rather than ghost stories.

If the libidinal motor of Lovecraft’s horror was race, in the case of James it was class. For James’ scholars, contact with the anomalous was usually mediated by the ‘lower classes’, which he portrayed as lacking in intellect but in possession of a deeper knowledge of weird lore. As Lovecraft and James scholar S T Joshi observes:

- The fractured and dialectical English in which [James’s array of lower-class characters] speak or write is, in one sense, a reflection of James’s well-known penchant for mimicry; but it cannot be denied that there is a certain element of malice in his relentless exhibition of their intellectual failings. […] And yet, they occupy pivotal places in the narrative: by representing a kind of middle ground between the scholarly protagonists and the aggressively savage ghosts, they frequently sense the presence of the supernatural more quickly and more instinctively than their excessively learned betters can bring themselves to do.

James wrote his stories as Christmas entertainments for Oxford undergraduates, and Smith was doubtless provoked and fascinated by James’ stories in part because there was no obvious point of identification for him in them. ‘When I was at the Witch trials of the 20th Century they said: You are white crap.’ (Live at the witch trials: is it that the witch trials have never ended or that we are in some repeating structure which is always excluding and denigrating the Weird?)

A working class autodidact like Smith could scarcely be conceived of in James’ sclerotically-stratified universe; such a being was a monstrosity which would be punished for the sheer hubris of existing. (Witness the amateur archaeologist Paxton in ‘A Warning to the Curious’. Paxton was an unemployed clerk and therefore by no means working class but his grisly fate was as much a consequence of ‘getting above himself’ as it was of his disturbing sacred Anglo-Saxon artefacts.) Smith could identify neither with James’ expensively-educated protagonists nor with his uneducated, superstitious lower orders. As Mark Sinker puts it: 'James, an enlightened Victorian intellectual, dreamed of the spectre of the once crushed and newly rising Working Classes as a brutish and irrational Monster from the Id: Smith is working class, and is torn between adopting this image of himself and fighting violently against it. It's left him with a loathing of liberal humanist condescension.'

But if Smith could find no place in James’ world, he would take a cue from one of Blake’s mottoes (adapted in Dragnet’s ‘Before the Moon Falls’) and create his own fictional system rather than be enslaved by another man’s. (Incidentally, isn’t Blake a candidate for being the original pulp modernist?) In James’ stories, there is, properly speaking, no working class at all. The lower classes that feature in his tales are by and large the remnants of the rural peasantry, and the supernatural is associated with the countryside. James’ scholars typically travel from Oxford or London to the witch-haunted flatlands of Suffolk, and it is only here that they encounter demonic entities. Smith’s fictions would locate spectres in the urban here and now; he would establish that their antagonisms were not archaisms.

- Sinker: No one has so perfectly studied the sense of threat in the English Horror Story: the twinge of apprehension at the idea that the wronged dead might return to claim their property, their identity, their own voice in their own land.

England: Look Back In Anguish, NME, 2 January 1988

The Grotesque Peasants stalk the Land

|  |

- Spectre Vs Rector: 'Detective vs. Rector (possessed by Spectre) / Spectre blows him against the wall. Says:/'Die wretch this is your fall /I've waited / Since Caesar for this. Damn Latin my /hate is crisp I'll rip your fat body to pieces'

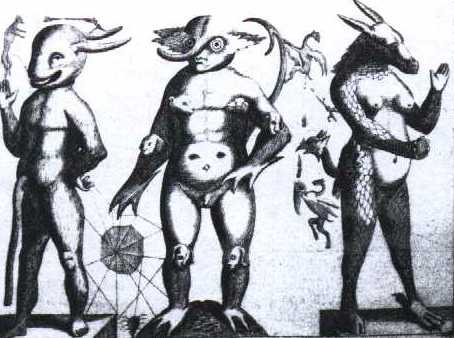

- Patrick Parrinder: 'The word grotesque derives from a type of Roman ornamental design first discovered in the fifteenth century, during the excavation of Titus's baths. Named after the "grottoes" in which they were found, the new forms consisted of human and animal shapes intermingled with foliage, flowers, and fruits in fantastic designs which bore no relationship to the logical categories of classical art. For a contemporary account of these forms we can turn to the Latin writer Vitruvius. Vitruvius was an official charged with the rebuilding of Rome under Augustus, to whom his treatise On Architecture is addressed. Not surprisingly, it bears down hard on the "improper taste" for the grotesque. "Such things neither are, nor can be, nor have been," says the author in his description of the mixed human, animal, and vegetable forms:

- 'For how can a reed actually sustain a roof, or a candelabrum the ornament of a gable? or a soft and slender stalk, a seated statue? or how can flowers and half-statues rise alternately from roots and stalks? Yet when people view these falsehoods, they approve rather than condemn, failing to consider whether any of them can really occur or not.'

By the time of Grotesque, The Fall's pulp modernism has become an entire political-aesthetic program. At one level, Grotesque can be positioned as the barbed Prole Art retort to the lyric antique Englishness of public school Prog. Compare, for instance, the cover of 'City Hobgoblins' (one of the singles that came out around the time of Grotesque) with something like Genesis' Nursery Cryme. Nursery Cryme presents a gently corrupted English surrealist idyll. On the 'City Hobgoblins' cover, an urban scene has been invaded by 'emigres from old green glades': a leering, malevolent cobold looms over a dilapidated tenement. But rather than being smoothly integrated into the photographed scene, the crudely rendered hobgoblin has been etched, Nigel Cooke-style, onto the background. This is a war of worlds, an ontological struggle, a struggle over the means of representation.

Grotesque's 'English Scheme' was a thumbnail sketch of the territory over which the war was being fought. Smith would observe later that it was 'English Scheme' which 'prompted me to look further into England's "class" system. INDEED, one of the few advantages of being in an impoverished sub-art group in England is that you get to see (If eyes are peeled) all the different strata of society - for free.' The enemies are the old Right, the custodians of a National Heritage image of England ('poky quaint streets in Cambridge') but also, crucially, the middle class Left, the Chabertistas of the time, who 'condescend to black men' and 'talk of Chile while driving through Haslingdon'. In fact, enemies were everywhere. Lumpen punk was in many ways more of a problem than prog, since its reductive literalism and perfunctory politics ('circles with A in the middle') colluded with Social Realism in censuring/ censoring the visionary and the ambitious.

Although Grotesque is an enigma, its title gives clues. Otherwise incomprehensible references to 'huckleberry masks', 'a man with butterflies on his face' and Totale's 'ostrich headress' and 'light blue plant-heads' begin to make sense when you recognize that, in Parrinder's description, the grotesque originally referred to 'human and animal shapes intermingled with foliage, flowers, and fruits in fantastic designs which bore no relationship to the logical categories of classical art'.

Grotesque, then, would be another moment in the endlessly repeating struggle between a Pulp Underground (the scandalous grottoes) and the Official culture, what Philip K Dick called 'the Black Iron Prison'. Dick's intuition was that 'the Empire had never ended', and that history was shaped by an ongoing occult(ed) conflict between Rome and Gnostic forces. 'Specter versus Rector' ('I've waited since Caesar for this') had rendered this clash in a harsh Murnau black and white ; on Grotesque the struggle is painted in colours as florid as those used on the album’s garish sleeve (the work of Smith's sister).

It is no accident that the words 'grotesque' and 'weird' are often associated with one another, since both connote something which is out of place, which either should not exist at all, or which should not exist here. The response to the apparition of a grotesque object will involve laughter as much as revulsion. 'What will be generally agreed upon,' Philip Thompson wrote in his 1972 study of The Grotesque 'is that "grotesque" will cover, perhaps among other things, the co-presence of the laughable and something that is incompatible with the laughable.' The role of laughter in The Fall has confused and misled interpreters. What has been suppressed is precisely the co-presence of the laughable with what is not compatible with the laughable. That co-presence is difficult to think, particularly in Britain, where humour has often functioned to ratify commonsense, to punish overreaching ambition with the dampening weight of bathos.

With The Fall, however, it is as if satire is returned to its origins in the grotesque. The Fall's laughter does not issue from the commonsensical mainstream but from a psychotic Outside. This is satire in the oneiric mode of Gillray, in which invective and lampoonery becomes delirial, a (psycho)tropological spewing of associations and animosities, the true object of which is not any failing of probity but the delusion that human dignity is possible. It is not surprising to find Smith alluding to Jarry’s Ubu Roi in a barely audible line in ‘City Hobgoblins’ (‘Ubu le Roi is a home hobgoblin’). For Jarry, as for Smith, the incoherence and incompleteness of the obscene and the absurd were to be opposed to the false symmetries of good sense.

But in their mockery of poise, moderation and self-containment, in their logorrheic disgorging of slanguage, in their glorying in mess and incoherence, The Fall sometimes resemble a white English analogue of Funkadelic. For both Smith and Clinton, there is no escaping the grotesque, if only because those who primp and puff themselves up only become more grotesque. We could go so far as to say that is the human condition to be grotesque, since the human animal is the one that does not fit in, the freak of nature who has no place in nature and is capable of re-combining nature’s products into hideous new forms.

On Grotesque, Smith has mastered his anti-lyrical methodology. The songs are tales, but tales half-told. The words are fragmentary, as if they have come to us via an unreliable transmission that keeps cutting out. Viewpoints are garbled; ontological distinctions (between author, text and character) are confused, fractured. It is impossible to definitively sort out the narrator’s words from direct speech. The tracks are palimpsests, badly recorded in a deliberate refusal of the ‘coffee table’ aesthetic Smith derides on the cryptic sleeve notes. The process of recording is not airbrushed out but foregrounded, surface hiss and illegible cassette noise brandished like improvised stitching on some Hammer Frankenstein monster.

‘Impression of J Temperance’ was typical: a story in the Lovecraft style in which a dog breeder’s ‘hideous replica’ (‘brown sockets…. Purple eyes… fed with rubbish from disposal barges…’) haunts Manchester. This is a Weird tale, but one subjected to modernist techniques of compression and collage. The result is so elliptical that it is as if the text – part-obliterated by silt, mildew and algae - has been fished out of the Manchester ship canal (which Hanley's bass sounds like it is dredging).

- ‘Yes,’ said Cameron. ‘And the thing was in the impression of J Temperance.’

The sound on Grotesque is a seemingly impossible combination of the shambolic and the disciplined, the ceberbral-literary and the idiotic-physical. The obvious parallel was The Birthday Party. In both groups, an implacable bass holds together a leering, lurching schizophonic body whose disparate elements strain like distended, diseased viscera against a pustule and pock-ridden skin (‘a spotty exterior hides a spotty interior’). Both The Fall and The Birthday Party reached for Pulp Horror imagery rescued from the white trash can as an analogue and inspiration for their perverse ‘return’ to rock and roll (cf also The Cramps). The nihilation that fired them was a rejection of a Pop that they saw as self-consciously sophisticated, conspicuously cosmopolitan, a Pop which implied that the arty could only be attained at the expense of brute physical impact. Their response was to hyperbolically emphasise crude atavism, to embrace the unschooled and the primitivist.

The Birthday Party’s fascination was with the American ‘junkonscious’, the mountain of semiotic/ narcotic trash lurking in the hindbrain of a world population hooked on America’s myths of abjection and omnipotence. The Birthday Party revelled in this fantasmatic Americana, using it as a way of cancelling an Australian identity that they in any case experienced as empty, devoid of any distinguishing features.

Smith’s r and r citations functioned differently, precisely as a means of reinforcing his Englishness and his own ambivalent attitude towards it. The rockabilly references are almost like ‘What If?’ exercises. What if rock and roll had emerged from the industrial heartlands of England rather than the Mississippi Delta? The rockabilly on ‘Container Drivers’ or ‘Fiery Jack’ is slowed by meat pies and gravy, its dreams of escape fatally poisoned by pints of bitter and cups of greasy spoon tea. It is rock and roll as Working Men’s Club cabaret, performed by a failed Gene Vincent imitator in Prestwich. The 'What if?' speculations fail. Rock and roll needed the endless open highways; it could never have begun in Britain's snarled up ring roads and claustrophobic conurbations.

For the Smith of Grotesque, homesickness is a pathology. (In the interview on the 1983 Perverted by Language video, Smith claims that being away from England literally made him sick.) There is little to recommend the country which he can never permanently leave; his relationship to it seems to be one of wearied addiction. The fake jauntiness of ‘English Scheme’ (complete with proto-John Shuttleworth cheesy cabaret keyboard) is a squalid postcard from somewhere no-one would ever wish to be. Here and in ‘C and Cs Mithering’, the US emerges as an alternative (in despair at the class-ridden Britain of ‘sixty hours and stone toilet back gardens’, the ‘clever ones’ ‘point their fingers at America’), but there is a sense that, no matter how far he travels, Smith will in the end be overcome by a compulsion to return to his blighted homeland, which functions as his pharmakon, his poison and remedy, sickness and cure. In the end he is as afflicted by paralysis as Joyce’s Dubliners.

On ‘C n Cs Mithering’ a rigor mortis snare drum gives this paralysis a sonic form. ‘C n Cs Mithering’ is an unstinting inventory of gripes and irritations worthy of Tony Hancock at his most acerbic and disconsolate, a cheerless survey of estates that ‘stick up like stacks’ and, worse still, a derisive dismissal of one of the supposed escape routes from drudgery: the music business, denounced as corrupt, dull and stupid. The track sounds, perhaps deliberately, like a white English version of rap (here as elsewhere, The Fall are remarkable for producing equivalents to, rather than facile imitations of, black American forms).

Body a Tentacle Mess

Cthulhu as painted by John Coulhart

- The N.W.R.A.: 'So R. Totale dwells underground/away from sickly grind/with ostrich head-dress/face a mess, covered in feathers/orange-red with blue-black lines/that draped down to his chest/body a tentacle mess/and light blue plant-heads.'

But it is the other long track, ‘N.W.R.A.’, that is the masterpiece. All of the LP’s themes coalesce in this track, a tale of cultural political intrigue that plays like some improbable mulching of T.S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, H. G. Wells, Dick, Lovecraft and Le Carre. It is the story of Roman Totale, a psychic and former cabaret performer whose body is covered in tentacles. It is often said that Roman Totale is one of Smith’s ‘alter-egos’; in fact, Smith is in the same relationship to Totale as Lovecraft was to someone like Randolph Carter. Totale is a character rather than a persona. Needless to say, he is not a character in the ‘well-rounded’ Forsterian sense so much as a carrier of mythos, an inter-textual linkage between Pulp fragments.

The inter-textual methodology is crucial to pulp modernism. If pulp modernism first of all asserts the author-function over the creative-expressive subject, it secondly asserts a fictional system against the author-God. By producing a fictional plane of consistency across different texts, the pulp modernist becomes a conduit through which a world can emerge. Once again, Lovecraft is the exemplar here: his tales and novellas could in the end no longer be apprehended as discrete texts but as part-objects forming a mythos-space which other writers could also explore and extend.

The form of ‘N.W.R.A.’ is as alien to organic wholeness as is Totale’s abominable tentacular body. It is a grotesque concoction, a collage of pieces that do not belong together. The model is the novella rather than the tale, and the story is told episodically, from multiple points of views, using a heteroglossic riot of styles and tones (comic, journalistic, satirical, novelistic): like ‘Call of Cthulhu’ re-written by the Joyce of Ulysses and compressed into ten minutes.

From what we can glean, Totale is at the centre of a plot – infiltrated and betrayed from the start – which aims at restoring the North to glory (perhaps to its Victorian moment of economic and industrial supremacy; perhaps to some more ancient pre-eminence, perhaps to a greatness that will eclipse anything that has come before). More than a matter of regional railing against the capital, in Smith’s vision the North comes to stand for everything suppressed by urbane good taste: the esoteric, the anomalous, the vulgar sublime, that is to say, the Weird and the Grotesque itself. Totale, festooned in the incongruous Grotesque costume of ‘ostrich head-dress … feathers/orange-red with blue-black lines/…and light blue plant-heads’, is the would-be Faery King of this Weird Revolt who ends up its maimed Fisher King, abandoned like a pulp modernist Miss Havisham amongst the relics of a carnival that will never happen, a drooling totem of a defeated tilt at Social Realism, the visionary leader reduced, as the psychotropics fade and the fervour cools, to being a washed-up cabaret artiste once again.