February 16, 2007

Memorex for the Krakens: The Fall's Pulp Modernism, part III

Don’t start improvising for Christ’s sake

The temptation, when writing about The Fall’s work of this period, is to too quickly render it tractable. I note this by way of a disclaimer and a confession, since I am of course as liable to fall prey to this temptation as any other commentator. To confidently describe songs as if they were ‘about’ settled subjects or to attribute to them a determinate aim or orientation (typically, a satirical purpose) will always be inadequate to the vertiginous experience of the songs and the distinctive jouissance provoked by listening to them. This enjoyment involves a frustration – a frustration, precisely, of our attempts to make sense of the songs. Yet this jouissance – something also provoked by the late Joyce, Pynchon and Burroughs - is an irreducible dimension of The Fall’s modernist poetics. If it is impossible to make sense of the songs, it is also impossible to stop making sense of them – or at least to it is impossible to stop attempting to make sense of them. On the one hand, there is no possibility of dismissing the songs as Nonsense; they are not gibberish or disconnected strings of non sequiturs. On the other hand, any attempt to constitute the songs as settled carriers of meaning runs aground on their incompleteness and inconsistency.

The principal way in which the songs were recuperated was via the charismatic persona Smith established in interviews. Although Smith scrupulously refused to either corroborate or reject any interpretations of his songs, invoking this extra-textual persona, notorious for its strong views and its sardonic but at least legible humour, allowed listeners and commentators to contain, even dissipate, the strangeness of the songs themselves.

The temptation to use Smith’s persona as a key to the songs was especially pressing because all pretence of democracy in the group has long since disappeared. By the time of Grotesque, it was clear that Smith was as much of an autocrat as James Brown, the band the zombie slaves of his vision. He is the shaman-author, the group the producers of a delirium-inducing repetition from which all spontaneity must be ruthlessly purged. ‘Don’t start improvising for Christ’s sake,’ goes a line on Slates, the 10” EP follow-up to Grotesque, echoing his chastisement of the band for ‘showing off’ on the live LP Totale’s Turns.

Slates’ ‘Prole Art Threat’ turned Smith’s persona, reputation and image into an enigma and a conspiracy. The song is a complex, ultimately unreadable, play on the idea of Smith as ‘working class’ spokesman. The ‘Theat’ is posed as much to other representations of the proletarian pop culture (which at its best meant The Jam and at its worst meant the more thuggish Oi!) as it is against the ruling class as such. The ‘art’ of The Fall’s pulp modernism – their intractability and difficulty – is counterposed to the misleading ingenuousness of Social Realism.

The Fall’s intuition was that social relations could not be understood in the ‘demystified’ terms of empirical observation (the ‘housing figures’ and ‘sociological memory’ later ridiculed on ‘The Man whose Head Expanded’). Social power depends upon ‘hexes’: restricted linguistic, gestural and behavioural codes which produce a sense of inferiority and enforce class destiny. ‘What chance have you got against a tie and a crest?’, Weller demanded on ‘Eton Rifles’, and it was as if The Fall took the power of such symbols and sigils very literally, understanding the social field as a series of curses which have to be sent back to those who had issued them.

The pulp format on ‘Prole Art Threat’ is Spy fiction, its scenario resembling Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy re-done as a tale of class cultural espionage, but then compressed and cut up so that characters and contexts are even more perplexing than they were even in Le Carre’s already oblique narrative. We are in a labyrinthine world of bluff and counter-bluff – a perfect analogue for Smith’s own elusive, allusive textual strategies. The text is presented to us as a transcript of surveillance tapes, complete with ellipses where the transmission is supposedly scrambled.

- GENT IN SAFE-HOUSE: Get out the pink press threat file

and Brrrptzzap* the subject. (* = scrambled) .

‘Prole Art Threat’ seems to be a satire, yet it is a blank satire, a satire without any clear object. If there is a point, it is precisely to disrupt any ‘centripetal’ effort to establish fixed identities and meanings. Those centripetal forces are represented by the ‘Middle Mass’ (‘vulturous in the aftermath’) and ‘the Victorian vampiric’ culture of London itself, as excoriated in ‘Leave the Capitol’:

- The tables covered in beer/ Showbiz whines, minute detail/ It’s a hand on the shoulder in Leicester Square/ It’s vaudeville pub back room dusty pictures of white frocked girls and music teachers/ The bed’s too clean/ The water’s poison for the system/ Then you know in your brain/ LEAVE THE CAPITOL! / EXIT THIS ROMAN SHELL!

This horrifying vision of London as a Stepford city of drab conformity ('hotel maids smile in unison') ends with the unexpected arrival of Machen’s Great God Pan (last alluded to in The Fall’s very early ‘Second Dark Age’), presaging The Fall's return of the Weird.

The textual expectorations of Hex

- Hex press release: 'He'd been very close to becoming ex-funny man celebrity. He needed a good hour at the hexen school...'

Hex Enduction Hour was even more expansive than Grotesque. Teeming with detail, gnomic yet hallucinogenically vivid, Hex was a series of pulp modernist pen portraits of England in 1982. The LP had all the hubristic ambition of Prog combined with an aggression whose ulcerated assault and battery outdid most of its postpunk peers in terms of sheer ferocity. Even the lumbering ‘Winter’ was driven by a brute urgency, so that, on Side One, only the quiet passages in the lugubrious ‘Hip Priest’ – like dub if it had been invented in drizzly motorway service stations rather than in recording studios in Jamaica – provided a respite from the violence.

Yet the violence was not a matter of force alone. Even when the record's dual-drummer attack is at its most poundingly vicious, the violence is formal as much as physical. Rock form is disassembled before our ears. It seems to keep time according to some system of spasms and lurches learned from Beefheart. Something like ‘Deer Park’ – a whistle-stop tour of London circa 82 sandblasted with ‘Sister Ray’-style white noise - screams and whines as if it is about to fall apart at any moment. The ‘bad production’ was nothing of the sort. The sound could be pulverisingly vivid at times: the moment when the bass and drums suddenly loom out of the miasma at the start of ‘Winter’ is breathtaking, and the double-drum tattoo on ‘Who Makes the Nazis?’ fairly leaps out of the speakers. This was the space rock of Can and Neu! smeared in the grime and mire of the quotidian, recalling the most striking image from The Quatermass Xperiment: a space rocket crashlanded into the roof of a suburban house.

In many ways, however, the most suggestive parallels come from black pop. The closest equivalents to the Smith of Hex would be the deranged despots of black sonic fiction: Lee Perry, Sun Ra and George Clinton, visionaries capable of constructing (and destroying) worlds in sound.

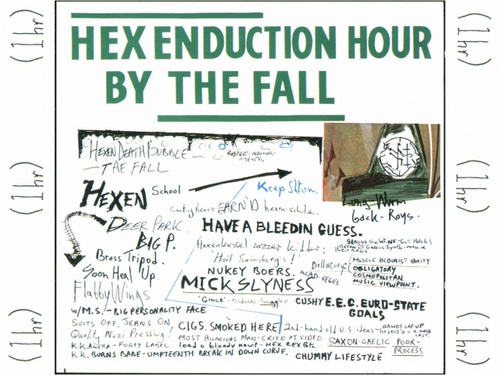

As ever, the album sleeve (so foreign to what were then the conventions of sleeve design that HMV would only stock it with its reverse side facing forward) was the perfect visual analogue for the contents. The sleeve was more than that, actually: its spidery scrabble of slogans, scrawled notes and photographs was a part of the album rather than a mere illustrative envelope in which it was contained.

With The Fall of this period, what Gerard Genette calls ‘paratexts’ – those liminal conventions, such as introductions, prefaces and blurbs, which mediate between the text and the reader – assume special significance. Smith’s paratexts were clues that posed as many puzzles as they solved; his notes and press releases were no more intelligible than the songs they were nominally supposed to explain. All paratexts occupy an ambivalent position, neither inside nor outside the text: Smith uses them to ensure that no definite boundary could be placed around the songs. Rather than being contained and defined by its sleeve, Hex haemorrhages through the cover.

It was clear that the songs weren’t complete in themselves, but part of a larger fictional system to which listeners were only ever granted partial access. ‘I used to write a lot of prose on and off,’ Smith would say later. ‘When we were doing Hex I was doing stories all the time and the songs were like the bits left over.’ Smith’s refusal to provide lyrics or to explain his songs was in part an attempt to ensure that they remained, in Barthes’ terms, writerly. (Barthes opposes such texts, which demand the active participation of the reader, to ‘readerly’ texts, which reduce the reader to the passive role of consumer of already-existing totalities.)

Before his words could be deciphered they had first of all to be heard, which was difficult enough, since Smith’s voice – often subject to what appeared to be loud hailer distortion - was always at least partially submerged in the mulch and maelstrom of Hex’s sound. In the days before the internet provided a repository of Smith’s lyrics (or fans’ best guesses at what the words were), it was easy to mis-hear lines for years.

Even when words could be heard, it was impossible to confidently assign them a meaning or an ontological ‘place’. Were they Smith’s own views, the thoughts of a character or merely stray semiotic signal? More importantly: how clearly could each of these levels be separated from one another? Hex’s textual expectorations were nothing so genteel as stream of consciousness: they seemed to be gobbets of linguistic detritus ejected direct from the mediatized unconscious, unfiltered by any sort of reflexive subjectivity. Advertising, tabloid headlines, slogans, pre-conscious chatter, overheard speech were masticated into dense schizoglossic tangles.

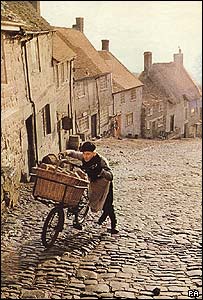

Who wants to be in a Hovis advert any way?

‘Who wants to be in a Hovis/ advert/ any way?’ Smith asks in ‘Just Step S’ways’, but this refusal of cosy provincial cliche (Hovis adverts were famous for their sentimentalised presentation of a bygone industrial North) is counteracted by the tacit recognition that the mediatized unconscious is structured like advertising. You might not want to live in an advert, but advertising dwells within you. Hex converts any linguistic content – whether it be polemic, internal dialogue, poetic insight – into the hectoring form of advertising copy or the screaming ellipsis of headline-speak. The titles of ‘Hip Priest’ and ‘Mere Pseud Mag Ed’, as urgent as fresh newsprint, bark out from some Voriticist front page of the mind.

As for advertising, consider ‘Just Step S’ways’’ opening call to arms: ‘When what you used to excite you does not/ like you’ve used up allow your allowance of experiences’. Is this an existentialist call for self re-invention disguised as advertising hucksterism, or the reverse? Or take the bilious opening track, ‘The Classical’. ‘The Classical’ appears to oppose the anodyne vacuity of advertising’s compulsory positivity (‘this new profile razor unit’) to ranting profanity (‘hey there fuckface!’) and the gross physicality of the body (‘stomach gassss’). But what of the line ‘I’ve never felt better in my life?’ Is this another advertising slogan or a statement of the character’s feelings?

It was perhaps the unplaceability of any of the utterances on Hex that allowed Smith to escape censure for the notorious line, ‘where are the obligatory niggers?’ in ‘The Classical’. Intent was unreadable. Everything sounded like a citation, embedded discourse, mention rather than use.

Smith returns to the Weird tale form on ‘Jawbone and the Air Rifle’. A poacher accidentally causes damage to a tomb, unearthing a jawbone which ‘carries the germ of a curse/ of the Broken Brothers Pentacle Church’. The song is a tissue of allusions - James (‘A Warning to the Curious’, ‘Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come to you, my Lad’), Lovecraft (‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’), Hammer Horror, The Wicker Man - culminating in a psychedelic/ psychotic breakdown (complete with torch-wielding mob of villagers):

- He sees jawbones on the street/ advertisements become carnivores/ and roadworkers turn into jawbones/ and he has visions of islands, heavily covered in slime. / The villagers dance round pre-fabs/ and laugh through twisted mouths

‘Jawbone’ resembles nothing so much as a League of Gentlemen sketch, and The Fall have much more in common with the League of Gentlemen’s febrile carnival than with witless imitators such as Pavement. The co-existence of the laughable with that which is not laughable: a description that captures the essence of both The Fall and The League of Gentlemen's grotesque humour.

White Face finds roots

- Moorcock: Below, black scars winding through the snow showed the main roads. Great frozen rivers and snow-laden forest stretched in all directions. Ahead they could just see a range of old, old mountatins. It was perpetual evening at this time of year, and the further north they went, the darker it became. The white lands seemed uninhabited, and Jerry could easily see how the legends of trolls, Jotunheim, and the tragic gods - the dark, cold, bleak legends of the North - had come out of Scandinavia. It made him feel strange, even anachronistic, as if he had gone back from his own age to the Ice Age. The Final Programme

'Iceland', recorded in a lava-lined studio in Reykjavik , is a fantasmatic encounter with the fading myths of North European culture in the frozen territory from which they originated. ‘White face finds roots’ Smith’s sleeve-notes tell us. The song, hypnotic and undulating, meditative and mournful, recalls the bone-white steppes of Nico's The Marble Index in its arctic atmospherics. A keening wind (on a cassette recording made by Smith) whips through the track as Smith invites us to ‘cast the runes against your own soul’ (another James’ reference, this time to his ‘Casting the Runes’).

‘Iceland’ is rock as ragnarock, an anticipation (or is it a recapitulation) of the End Times in the terms of the Norse ‘Doom of the Gods’. It is a Twilight of the Idols for the retreating hobgoblins, cobolds and trolls of Europe’s receding Weird culture, a lament for the monstrosities and myths whose dying breaths it captures on tape:

- Witness the last of the god men ….

A Memorex for the Krakens