February 04, 2007

Memorex for the Krakens: The Fall's Pulp Modernism (part II)

(AT LAST - and they said it would not be done!: Part II - but - be warned - there is still a Part III to follow.) (Part I is here)

M R James, be born be born

- City Hobgoblins: 'Ten times my age, one tenth my height...'

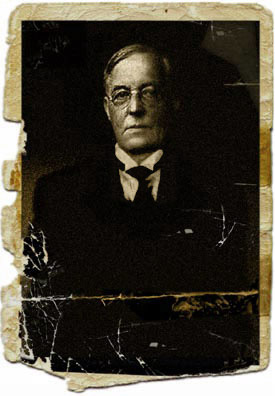

- Mark Sinker: So he plunges into the Twilight World, and a political discourse framed in terms of witch-craft and demons. It's not hard to understand why, once you start considering it. The war that the Church and triumphant Reason waged on a scatter of wise-women and midwives, lingering practitioners of folk-knowledge, has provided a powerful popular image for a huge struggle for political and intellectual dominance, as first Catholics and later Puritans invoked a rise in devil-worship to rubbish their opponents. The ghost-writer and antiquarian M.R. James (one of the writers Smith appears to have lived on during his peculiar drugged adolescence) transformed the folk-memory into a bitter class-struggle between established science and law, and the erratic, vengeful, relentless undead world of wronged spirits, cheated of property or voice, or the simple dignity of being believed in.' 'Watching the City Hobgoblins', The Wire, August 1986

Whether Smith first came to James via TV or some other route, James’ stories exerted a powerful and persistent influence on his writing. Lovecraft, an enthusiastic admirer of James' stories to the degree that he borrowed their structure (scholar/ researcher steeped in empiricist common sense is gradually driven insane by contact with an abyssal alterity) understood very well what was novel in James' tales. ‘In inventing a new type of ghost,’ Lovecraft wrote of James, ‘he departed considerably from the conventional Gothic traditions; for where the older stock ghosts were pale and stately, and apprehended chiefly through the sense of sight, the average James ghost is lean, dwarfish and hairy – a sluggish, hellish night-abomination midway betwixt beast and man – and usually touched before it is seen.’ Some would question whether these dwarven figures ('ten times my age, one tenth my height') could be described as ‘ghosts’ at all; often, it seemed that James was writing demon rather than ghost stories.

If the libidinal motor of Lovecraft’s horror was race, in the case of James it was class. For James’ scholars, contact with the anomalous was usually mediated by the ‘lower classes’, which he portrayed as lacking in intellect but in possession of a deeper knowledge of weird lore. As Lovecraft and James scholar S T Joshi observes:

- The fractured and dialectical English in which [James’s array of lower-class characters] speak or write is, in one sense, a reflection of James’s well-known penchant for mimicry; but it cannot be denied that there is a certain element of malice in his relentless exhibition of their intellectual failings. […] And yet, they occupy pivotal places in the narrative: by representing a kind of middle ground between the scholarly protagonists and the aggressively savage ghosts, they frequently sense the presence of the supernatural more quickly and more instinctively than their excessively learned betters can bring themselves to do.

James wrote his stories as Christmas entertainments for Oxford undergraduates, and Smith was doubtless provoked and fascinated by James’ stories in part because there was no obvious point of identification for him in them. ‘When I was at the Witch trials of the 20th Century they said: You are white crap.’ (Live at the witch trials: is it that the witch trials have never ended or that we are in some repeating structure which is always excluding and denigrating the Weird?)

A working class autodidact like Smith could scarcely be conceived of in James’ sclerotically-stratified universe; such a being was a monstrosity which would be punished for the sheer hubris of existing. (Witness the amateur archaeologist Paxton in ‘A Warning to the Curious’. Paxton was an unemployed clerk and therefore by no means working class but his grisly fate was as much a consequence of ‘getting above himself’ as it was of his disturbing sacred Anglo-Saxon artefacts.) Smith could identify neither with James’ expensively-educated protagonists nor with his uneducated, superstitious lower orders. As Mark Sinker puts it: 'James, an enlightened Victorian intellectual, dreamed of the spectre of the once crushed and newly rising Working Classes as a brutish and irrational Monster from the Id: Smith is working class, and is torn between adopting this image of himself and fighting violently against it. It's left him with a loathing of liberal humanist condescension.'

But if Smith could find no place in James’ world, he would take a cue from one of Blake’s mottoes (adapted in Dragnet’s ‘Before the Moon Falls’) and create his own fictional system rather than be enslaved by another man’s. (Incidentally, isn’t Blake a candidate for being the original pulp modernist?) In James’ stories, there is, properly speaking, no working class at all. The lower classes that feature in his tales are by and large the remnants of the rural peasantry, and the supernatural is associated with the countryside. James’ scholars typically travel from Oxford or London to the witch-haunted flatlands of Suffolk, and it is only here that they encounter demonic entities. Smith’s fictions would locate spectres in the urban here and now; he would establish that their antagonisms were not archaisms.

- Sinker: No one has so perfectly studied the sense of threat in the English Horror Story: the twinge of apprehension at the idea that the wronged dead might return to claim their property, their identity, their own voice in their own land.

England: Look Back In Anguish, NME, 2 January 1988

The Grotesque Peasants stalk the Land

|  |

- Spectre Vs Rector: 'Detective vs. Rector (possessed by Spectre) / Spectre blows him against the wall. Says:/'Die wretch this is your fall /I've waited / Since Caesar for this. Damn Latin my /hate is crisp I'll rip your fat body to pieces'

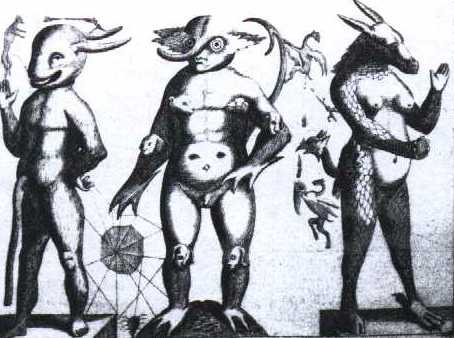

- Patrick Parrinder: 'The word grotesque derives from a type of Roman ornamental design first discovered in the fifteenth century, during the excavation of Titus's baths. Named after the "grottoes" in which they were found, the new forms consisted of human and animal shapes intermingled with foliage, flowers, and fruits in fantastic designs which bore no relationship to the logical categories of classical art. For a contemporary account of these forms we can turn to the Latin writer Vitruvius. Vitruvius was an official charged with the rebuilding of Rome under Augustus, to whom his treatise On Architecture is addressed. Not surprisingly, it bears down hard on the "improper taste" for the grotesque. "Such things neither are, nor can be, nor have been," says the author in his description of the mixed human, animal, and vegetable forms:

- 'For how can a reed actually sustain a roof, or a candelabrum the ornament of a gable? or a soft and slender stalk, a seated statue? or how can flowers and half-statues rise alternately from roots and stalks? Yet when people view these falsehoods, they approve rather than condemn, failing to consider whether any of them can really occur or not.'

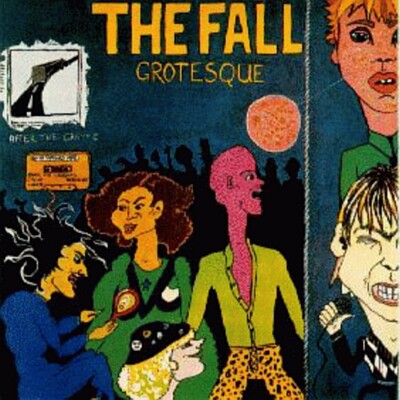

By the time of Grotesque, The Fall's pulp modernism has become an entire political-aesthetic program. At one level, Grotesque can be positioned as the barbed Prole Art retort to the lyric antique Englishness of public school Prog. Compare, for instance, the cover of 'City Hobgoblins' (one of the singles that came out around the time of Grotesque) with something like Genesis' Nursery Cryme. Nursery Cryme presents a gently corrupted English surrealist idyll. On the 'City Hobgoblins' cover, an urban scene has been invaded by 'emigres from old green glades': a leering, malevolent cobold looms over a dilapidated tenement. But rather than being smoothly integrated into the photographed scene, the crudely rendered hobgoblin has been etched, Nigel Cooke-style, onto the background. This is a war of worlds, an ontological struggle, a struggle over the means of representation.

Grotesque's 'English Scheme' was a thumbnail sketch of the territory over which the war was being fought. Smith would observe later that it was 'English Scheme' which 'prompted me to look further into England's "class" system. INDEED, one of the few advantages of being in an impoverished sub-art group in England is that you get to see (If eyes are peeled) all the different strata of society - for free.' The enemies are the old Right, the custodians of a National Heritage image of England ('poky quaint streets in Cambridge') but also, crucially, the middle class Left, the Chabertistas of the time, who 'condescend to black men' and 'talk of Chile while driving through Haslingdon'. In fact, enemies were everywhere. Lumpen punk was in many ways more of a problem than prog, since its reductive literalism and perfunctory politics ('circles with A in the middle') colluded with Social Realism in censuring/ censoring the visionary and the ambitious.

Although Grotesque is an enigma, its title gives clues. Otherwise incomprehensible references to 'huckleberry masks', 'a man with butterflies on his face' and Totale's 'ostrich headress' and 'light blue plant-heads' begin to make sense when you recognize that, in Parrinder's description, the grotesque originally referred to 'human and animal shapes intermingled with foliage, flowers, and fruits in fantastic designs which bore no relationship to the logical categories of classical art'.

Grotesque, then, would be another moment in the endlessly repeating struggle between a Pulp Underground (the scandalous grottoes) and the Official culture, what Philip K Dick called 'the Black Iron Prison'. Dick's intuition was that 'the Empire had never ended', and that history was shaped by an ongoing occult(ed) conflict between Rome and Gnostic forces. 'Specter versus Rector' ('I've waited since Caesar for this') had rendered this clash in a harsh Murnau black and white ; on Grotesque the struggle is painted in colours as florid as those used on the album’s garish sleeve (the work of Smith's sister).

It is no accident that the words 'grotesque' and 'weird' are often associated with one another, since both connote something which is out of place, which either should not exist at all, or which should not exist here. The response to the apparition of a grotesque object will involve laughter as much as revulsion. 'What will be generally agreed upon,' Philip Thompson wrote in his 1972 study of The Grotesque 'is that "grotesque" will cover, perhaps among other things, the co-presence of the laughable and something that is incompatible with the laughable.' The role of laughter in The Fall has confused and misled interpreters. What has been suppressed is precisely the co-presence of the laughable with what is not compatible with the laughable. That co-presence is difficult to think, particularly in Britain, where humour has often functioned to ratify commonsense, to punish overreaching ambition with the dampening weight of bathos.

With The Fall, however, it is as if satire is returned to its origins in the grotesque. The Fall's laughter does not issue from the commonsensical mainstream but from a psychotic Outside. This is satire in the oneiric mode of Gillray, in which invective and lampoonery becomes delirial, a (psycho)tropological spewing of associations and animosities, the true object of which is not any failing of probity but the delusion that human dignity is possible. It is not surprising to find Smith alluding to Jarry’s Ubu Roi in a barely audible line in ‘City Hobgoblins’ (‘Ubu le Roi is a home hobgoblin’). For Jarry, as for Smith, the incoherence and incompleteness of the obscene and the absurd were to be opposed to the false symmetries of good sense.

But in their mockery of poise, moderation and self-containment, in their logorrheic disgorging of slanguage, in their glorying in mess and incoherence, The Fall sometimes resemble a white English analogue of Funkadelic. For both Smith and Clinton, there is no escaping the grotesque, if only because those who primp and puff themselves up only become more grotesque. We could go so far as to say that is the human condition to be grotesque, since the human animal is the one that does not fit in, the freak of nature who has no place in nature and is capable of re-combining nature’s products into hideous new forms.

On Grotesque, Smith has mastered his anti-lyrical methodology. The songs are tales, but tales half-told. The words are fragmentary, as if they have come to us via an unreliable transmission that keeps cutting out. Viewpoints are garbled; ontological distinctions (between author, text and character) are confused, fractured. It is impossible to definitively sort out the narrator’s words from direct speech. The tracks are palimpsests, badly recorded in a deliberate refusal of the ‘coffee table’ aesthetic Smith derides on the cryptic sleeve notes. The process of recording is not airbrushed out but foregrounded, surface hiss and illegible cassette noise brandished like improvised stitching on some Hammer Frankenstein monster.

‘Impression of J Temperance’ was typical: a story in the Lovecraft style in which a dog breeder’s ‘hideous replica’ (‘brown sockets…. Purple eyes… fed with rubbish from disposal barges…’) haunts Manchester. This is a Weird tale, but one subjected to modernist techniques of compression and collage. The result is so elliptical that it is as if the text – part-obliterated by silt, mildew and algae - has been fished out of the Manchester ship canal (which Hanley's bass sounds like it is dredging).

- ‘Yes,’ said Cameron. ‘And the thing was in the impression of J Temperance.’

The sound on Grotesque is a seemingly impossible combination of the shambolic and the disciplined, the ceberbral-literary and the idiotic-physical. The obvious parallel was The Birthday Party. In both groups, an implacable bass holds together a leering, lurching schizophonic body whose disparate elements strain like distended, diseased viscera against a pustule and pock-ridden skin (‘a spotty exterior hides a spotty interior’). Both The Fall and The Birthday Party reached for Pulp Horror imagery rescued from the white trash can as an analogue and inspiration for their perverse ‘return’ to rock and roll (cf also The Cramps). The nihilation that fired them was a rejection of a Pop that they saw as self-consciously sophisticated, conspicuously cosmopolitan, a Pop which implied that the arty could only be attained at the expense of brute physical impact. Their response was to hyperbolically emphasise crude atavism, to embrace the unschooled and the primitivist.

The Birthday Party’s fascination was with the American ‘junkonscious’, the mountain of semiotic/ narcotic trash lurking in the hindbrain of a world population hooked on America’s myths of abjection and omnipotence. The Birthday Party revelled in this fantasmatic Americana, using it as a way of cancelling an Australian identity that they in any case experienced as empty, devoid of any distinguishing features.

Smith’s r and r citations functioned differently, precisely as a means of reinforcing his Englishness and his own ambivalent attitude towards it. The rockabilly references are almost like ‘What If?’ exercises. What if rock and roll had emerged from the industrial heartlands of England rather than the Mississippi Delta? The rockabilly on ‘Container Drivers’ or ‘Fiery Jack’ is slowed by meat pies and gravy, its dreams of escape fatally poisoned by pints of bitter and cups of greasy spoon tea. It is rock and roll as Working Men’s Club cabaret, performed by a failed Gene Vincent imitator in Prestwich. The 'What if?' speculations fail. Rock and roll needed the endless open highways; it could never have begun in Britain's snarled up ring roads and claustrophobic conurbations.

For the Smith of Grotesque, homesickness is a pathology. (In the interview on the 1983 Perverted by Language video, Smith claims that being away from England literally made him sick.) There is little to recommend the country which he can never permanently leave; his relationship to it seems to be one of wearied addiction. The fake jauntiness of ‘English Scheme’ (complete with proto-John Shuttleworth cheesy cabaret keyboard) is a squalid postcard from somewhere no-one would ever wish to be. Here and in ‘C and Cs Mithering’, the US emerges as an alternative (in despair at the class-ridden Britain of ‘sixty hours and stone toilet back gardens’, the ‘clever ones’ ‘point their fingers at America’), but there is a sense that, no matter how far he travels, Smith will in the end be overcome by a compulsion to return to his blighted homeland, which functions as his pharmakon, his poison and remedy, sickness and cure. In the end he is as afflicted by paralysis as Joyce’s Dubliners.

On ‘C n Cs Mithering’ a rigor mortis snare drum gives this paralysis a sonic form. ‘C n Cs Mithering’ is an unstinting inventory of gripes and irritations worthy of Tony Hancock at his most acerbic and disconsolate, a cheerless survey of estates that ‘stick up like stacks’ and, worse still, a derisive dismissal of one of the supposed escape routes from drudgery: the music business, denounced as corrupt, dull and stupid. The track sounds, perhaps deliberately, like a white English version of rap (here as elsewhere, The Fall are remarkable for producing equivalents to, rather than facile imitations of, black American forms).

Body a Tentacle Mess

Cthulhu as painted by John Coulhart

- The N.W.R.A.: 'So R. Totale dwells underground/away from sickly grind/with ostrich head-dress/face a mess, covered in feathers/orange-red with blue-black lines/that draped down to his chest/body a tentacle mess/and light blue plant-heads.'

But it is the other long track, ‘N.W.R.A.’, that is the masterpiece. All of the LP’s themes coalesce in this track, a tale of cultural political intrigue that plays like some improbable mulching of T.S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis, H. G. Wells, Dick, Lovecraft and Le Carre. It is the story of Roman Totale, a psychic and former cabaret performer whose body is covered in tentacles. It is often said that Roman Totale is one of Smith’s ‘alter-egos’; in fact, Smith is in the same relationship to Totale as Lovecraft was to someone like Randolph Carter. Totale is a character rather than a persona. Needless to say, he is not a character in the ‘well-rounded’ Forsterian sense so much as a carrier of mythos, an inter-textual linkage between Pulp fragments.

The inter-textual methodology is crucial to pulp modernism. If pulp modernism first of all asserts the author-function over the creative-expressive subject, it secondly asserts a fictional system against the author-God. By producing a fictional plane of consistency across different texts, the pulp modernist becomes a conduit through which a world can emerge. Once again, Lovecraft is the exemplar here: his tales and novellas could in the end no longer be apprehended as discrete texts but as part-objects forming a mythos-space which other writers could also explore and extend.

The form of ‘N.W.R.A.’ is as alien to organic wholeness as is Totale’s abominable tentacular body. It is a grotesque concoction, a collage of pieces that do not belong together. The model is the novella rather than the tale, and the story is told episodically, from multiple points of views, using a heteroglossic riot of styles and tones (comic, journalistic, satirical, novelistic): like ‘Call of Cthulhu’ re-written by the Joyce of Ulysses and compressed into ten minutes.

From what we can glean, Totale is at the centre of a plot – infiltrated and betrayed from the start – which aims at restoring the North to glory (perhaps to its Victorian moment of economic and industrial supremacy; perhaps to some more ancient pre-eminence, perhaps to a greatness that will eclipse anything that has come before). More than a matter of regional railing against the capital, in Smith’s vision the North comes to stand for everything suppressed by urbane good taste: the esoteric, the anomalous, the vulgar sublime, that is to say, the Weird and the Grotesque itself. Totale, festooned in the incongruous Grotesque costume of ‘ostrich head-dress … feathers/orange-red with blue-black lines/…and light blue plant-heads’, is the would-be Faery King of this Weird Revolt who ends up its maimed Fisher King, abandoned like a pulp modernist Miss Havisham amongst the relics of a carnival that will never happen, a drooling totem of a defeated tilt at Social Realism, the visionary leader reduced, as the psychotropics fade and the fervour cools, to being a washed-up cabaret artiste once again.

Posted by mark at February 4, 2007 10:53 PM | TrackBack