January 29, 2007

Speaking of cultural exhaustion...

I dunno, reading these quotes from the Klaxons, you can't help but think: if anyone ever wanted to make a Spinal Tap-type movie about Indie Dance.... To be fair, I haven't heard the album, but what I have heard puts me in mind of beery bargain basement chancers like EMF and Jesus Jones...

And how tired is this: 'All the dance bands relied on electronic programming and drum machines. We wanted to take that and give it a human element.' Because, naturally, what rave was deficient in was 'organic' and 'human' elements. Pointless rhetorical questions... Just why is it that indie bands think that transforming rave/ hip hop/ house/ r and b into plodding pub rock bluster is either necessary or interesting? Why is it unimaginable that they would say 'we want to remove the vestigial human components and make a sound even more abstract, impersonal and strange....'?

January 26, 2007

coffee bars and internment camps

I've finally seen Children of Men, on DVD, after missing it at the cinema. Watching it last week I asked myself, why is its rendering of apocalyspe so contemporary?

British cinema, for the last thirty years as chronically sterile as the issueless popluation in Children of Men, has not produced a version of the apocalypse that is even remotely as well realised as this. You would have to turn to television - to the last Quatermass serial or to Threads, almost certainly the most harrowing television programme ever broadcast on British TV - for a vision of British society in collapse that is as compelling. Yet the comparison between Children of Men and these two predecessors points to what is unique about the film; the final Quatermass serial and Threads still belonged to Nuttall's bomb culture, but the anxieties with which Children of Men deals have nothing to do with nuclear war.

Children of Men reinforces what few would doubt, but which British cinema would seldom lead you to suspect: the British landscape bristles with cinematic potential. It's long since been evident that only someone outside the self-serving, self-pitying low gene pool of British cinema is capable of realising this potential, and Children of Men's director, Alfonso Cuarón, and cinematographer, Emmanuel Lubezki, are both Mexican. Together they have produced a portrait of Grim Britannia that is like a film equivalent of the Burial LP (and the film's excellent soundtrack features Burial's mentor and label-mate, Kode9).

Lubezki's cinematography is breathtaking. His photography seems to leech all organic and naturalistic vitality from the images, leaving them a washed-out grey-blue. The effect is something like a visual equivalent of the 'muting' about which Woebot speaks so eloquently in his latest broadcast. As David Edelstein put it in an insightful review in New York Magazine: ' The movie calls to mind an early description in Cormac McCarthy’s overwrought but gripping post-apocalypse novel The Road of gray days “like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world.”' The lighting is masterly: it as if the whole film takes place in a permanent winter afternoon when even the sun is dying. White smoke, its source unspecified, curls ubiquitously.

Cuarón's trick is to combine this despondent lyricism with a formal realism, achieved through the expert use of hand-held camera and long takes. Blood spatters onto the camera lens and goes unwiped. The gunfire is as oppressively tactile as it was in Saving Private Ryan. The meticulously choreographed long takes - technical feats of some magnitude - have justly been highly praised, and they are all the more remarkable because they go beyond the familiar role of simulating documentary realism to serve a political and artistic vision.

This brings us back, then, to my initial question, and I think that there are three reasons that Children of Men is so contemporary.

Firstly, the film is dominated by the sense that the damage has been done. The catastrophe is neither waiting down the road, nor has it already happened. Rather, it is being lived through. There is no punctual moment of disaster; the world doesn't end with a bang, it winks out, unravels, gradually falls apart. What caused the catastrophe to occur, who knows; its cause lies long in the past, so absolutely detached from the present as to seem like the caprice of a malign being: a negative miracle, a malediction which no penitence can ameliorate. Such a blight can only be eased by an intervention that can no more be anticipated than was the onset of the curse in the first place. Action is pointless; only senseless hope makes sense. Superstition and religion, the first resorts of the helpless, proliferate.

Secondly, Children of Men is a dystopia that is specific to late capitalism. This isn't the familiar totalitarian scenario routinely trotted out in cinematic dystopias (see, for example, V for Vendetta, which, incidentally, compares badly with Children of Men on every point).

If, as Wendy Brown has so persuasively argued, neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism can be made compatible only at the level of dreamwork, then Children of Men renders this oneiric suturing as a nightmare. In Children of Men, public space is abandoned, given over to uncollected garbage and to stalking animals (one especially resonant scene takes place inside a derelict school, through which a deer runs). But, contrary to neo-liberal fantasy, there is no withering away of the State, only a stripping back of the State to its core military and police functions. In this world, as in ours, ultra-authoritarianism and Capital are by no means incompatible: internment camps and franchise coffee bars co-exist.

In P.D. James' novel, democracy is suspended and the country is ruled over by a self-appointed Warden. Wisely, the film downplays all this. For all that we know, the Britain of the film could still be a democracy, and the authoritarian measures that are everywhere in place could have been implemented within a political structure that remains, notionally, democratic. The War on Terror has prepared us for such a development: the normalisation of crisis produces a situation in which the repealing of measures brought in to deal with an emergency becomes unimaginable (when will the war be over?) Democratic rights and freedoms (habeas corpus, free speech and assembly) are suspended while democracy is still proclaimed.

Children of Men extrapolates rather than exaggerates. At a certain point, realism flips over into delirium. Bad dream logic takes hold as you go through the gates of the Refugee Camp at Bexhill. You pass through buildings that were once public utilities into an indeterminate space - Hell as a Temporary Autonomous Zone - in which laws, both juridical and metaphysical, are suspended. A carnival of brutality is underway. By now, you are homo sacer so there's no point complaining about the beatings. You could be anywhere, provided it's a warzone: Yugoslavia in the 90s, Baghdad in the 00s, Palestine any time. Graffiti promises an intifada, but the odds are overwhelmingly stacked in favour of the State, which still packs the most powerful weapons.

The third reason that Children of Men works is because of its take on cultural crisis. It's evident that the theme of sterility must be read metaphorically, as the displacement of another kind of anxiety. (If the sterility were to be taken literally, the film would be no more than a requiem for what Lee Edelman calls 'reproductive futurism', entirely in line with mainstream culture's pathos of fertility.) For me, this anxiety cries out to be read in cultural terms, and the question the film poses is: how long can a culture persist without the new? What happens if the young are no longer capable of producing surprises?

Children of Men connects with the suspicion that the end has already come, the thought that it could well be the case that the future harbours only reiteration and repermutation. Could it be, that is to say, that there are no breaks, no 'shocks of the new' to come? Such anxieties tend to result in a bi-polar oscillation: the 'weak messianic' hope that there must be something new on the way lapses into the morose conviction that nothing new can ever happen. The focus shifts from the Next Big Thing to the last big thing - how long ago did it happen and just how big was it?

The key scene in which the cultural theme is explicitly broached comes when Clive Owen's character, Theo, visits a friend Battersea power station, which is now some combination of government building and private collection. Cultural treasures - Michelangelo's David, Picasso's Geurnica, Pink Floyd's inflatable pig - are preserved in a building that is itself a refurbished heritage artefact. This is our only gilmpse into the lives of the elite. The distinction between their life and that of the lower orders is marked, as ever, by differential access to enjoyment: they still eat their artfully presented cusisine in the shadow of the Old Masters. Theo, asks the question how all this can matter if there will be no-one to see it? The alibi can no longer be future generations, since there will be none. The response is nihilistic hedonism: 'I try not to think about it'.

T.S. Eliot looms in the background of Children of Men, which, after all, inherits the theme of sterility from The Waste Land. The film's closing epigraph 'shantih shantih shantih' has more to do with Eliot's fragmentary pieces than the Upanishads' peace. Perhaps it is possible to see the concerns of another Eliot - the Eliot of 'Tradition and the Individual Talent' - ciphered in Children of Man. It was in this essay that Eliot, in anticipation of Bloom, described the reciprocal relationship between the canonical and the new. The new defines itself in response to what is already established; at the same time, the established has to reconfigure itself in response to the new. Eliot's claim was that the exhaustion of the future does not even leave us with the past. Tradition counts for nothing when it is no longer contested and modified. A culture that is merely preserved is no culture at all. The fate of Picasso's Geurnica - once a howl of anguish and outrage against Fascist atrocities, now a wall-hanging - is exemplary. Like its Battersea hanging space in the film, the painting is accorded 'iconic' status only when it is deprived of any possible function or context.

A culture which takes place only in museums is already exhausted. A culture of commemoration is a cemetry. No cultural object can retain its power when there are no longer new eyes to see it.

January 25, 2007

January 24, 2007

Well worth supporting

... if you can make it to Hackney this weekend...

Further details here...

Note that the venue has been changed to 90 Wallis Road...

Proleface

For those who haven't seen them, there are good pieces on Jade Goody at Antigram, Charlotte Street and the Weblog (see also the response to this last at Foucault is Dead).

Antigram's question is well-posed: 'A millionaire lumpen prole gargolyle on the one hand, a glamorous Bollywood actress on the other: is this, then, what we supposed to believe constitutes the class divide running down the middle of this country?' Part of the displacement of the class question in the culture is that class tensions can only appear in this caricatured form. The freakshow exhibiting of Jade is all of a piece with Channel 4's fascinated-repelled depiction of the working class as in need of makeovers, domestic training or education about diet (Ten Years Younger/ How Clean is your House? / You are what you Eat). The much-hyped Shameless, with its silly, overwrought stereotypes, strikes me as part of this Proleface trend, actually. It goes without saying that Goody's impotent acting out of class resentments confirms, rather than challenges, the representational grid in which she is enmeshed.

The comparison between Goody and her defender Julie Burchill tells us a great deal about how class relations and prospects have changed over the last thirty years. Burchill benefited from an earlier version of the ruling class fascination/ repulsion with proletariat; in her case, the progression from self-taught intellectual Marxist firebrand to prole-for-hire ('some of them can even write proper sentences, don't you know') had its tragic dimensions, its disappointments and betrayals. Yet Burchill's presence has always been about working class intelligence, the very possibility of which Jade Goody's success has implicitly denied.

January 19, 2007

Classist jouissance

Three interesting posts on new Lacanian blog Foucault is Dead about Celebrity Big Brother.

The rather unedifying furore provoked by CBB this year presents a very depressing picture of Britain in 2007. Initially, it was gratifying to see so many members of the public complain about the treatment of Shilpa Shetty. Yet, it quickly became apparent that there was another jouissance in play here: as Foucault is Dead correctly notes, the enjoyment of castigating Jade, of anticipating the derision and humilation she will face once she leaves the house, involves, undoubtedly, a classist jouissance. Under the cover of defending a housemate from racism, the media and the public have indulged in a slew of class hatred.

Goody's behaviour in the house makes it clear that class is about a sense of inferiority which cannot be ameliorated by the acquisition of wealth (she is reputedly worth several million pounds). Goody's role in the national pantomime since she rose to fame has been to play the role of lumpen proletarian gargoyle: inarticulate, lacking in basic general knowledge, prone to flying into ecstasies of rage such as she subjected Shetty to the other day. Such behaviour has been alternately reviled and rewarded - Goody's success was based on a wave of sympathy which followed a similar monstering when she appeared on Big Brother the first time - so it shouldn't be surprising if Goody is confused about how to act. This is not to excuse Goody's actions - but her behaviour cannot be separated from the class impasses of British society, which more than ever trap the working class in miserable self-denigration and low self-confidence (even if those traits are concealed behind boorish bravado and conspicuous hedonism).

While Goody and her compatriots have certainly bullied Shetty, I agree with Foucault is Dead that the treatment of the actress has not been straightforwardly racist. There have been racist remarks, but the central dynamic appears to be resentment and jealousy rather than racial hatred. There are certain structural similarities with racism in that the housemates who have attacked Shetty have done so on the basis of fantasies about the enjoyment of the other: Shetty, for instance, is held to have been given privileged treatment by Big Brother.

It is pleasing that the debate around the programme has concerned whether or not racism has happened rather than whether racism is acceptable or not. But it is worth thinking about why postmodern media abominates racism (at the level of discourse; it has, of course, done little to tackle racism and a structural problem) but is worryingly silent about class.

Incidentally, those looking forward to the ending of Jade's career are sure to be disappointed. The soap opera rhythm of postmodern media will not alllow it. The routine is now familiar: a rash of cancelled contracts, period of silence, followed by triumphant, contrite, return.

January 18, 2007

Image management in the Imperium

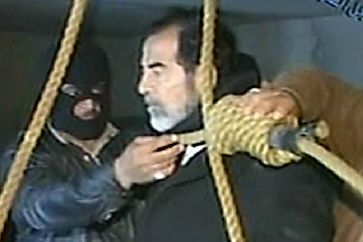

There is no better illustration of American cultural entropy, of the sense that things have finished but they continue to grind on, than Saddam's execution. The scene is appalling, of course, in the way that all executions must be: the contrast between the quotidian dreariness of the surroundings and the terrible metaphysical threshold over which the executed individual must pass; the squalid brutality of the act of pre-meditated killing, which remains brutal and squalid no matter how atrocious the crimes of the condemned were. Films of live death are attempts to screen the Real, but, inevitably, the Real of death cannot be captured. What we are left with, instead, is another reality TV moment, recorded on mobile phone videocamera and distributed by YouTube. It begins with Shock and Awe and ends in Snuff...

The significance of the sounds and images of Saddam's execution resides in what is absent from them: namely, any sense of ceremony. The images confirm the impression that, far from being the gleaming citadel of a nascent democracy (even Bush has given up on that pretence) Iraq is given over to casual atrocity, lynching and civil disorder.

The execution is a reminder that the American-led invasion of Iraq has singularly failed to produce any images that possess Symbolic efficacy. There is very far from being any equivalent of the flag-raising at Iwo Jima: an image powerful enough to itself constitute an incorporeal transformation. The scenes of Saddam's statue being felled, all too obviously staged, played like a weak echo of similar, more powerful, scenes at the close of the Cold War.

The failure of image management is no trivial matter. We might go so far as to say that this alone indicates the final failure of the Neo-Conservative project, which, after all, was supposed to be about generating popular images and myths. No image which the US military-industrial-entertainment complex has produced in the last half decade can compare even remotely with the TV pictures of the twin towers collapsing, which remain - by some distance - the most significant semiotic event of the century. Instead of countering 9/11, indeed, the images of US bombing raids on Afghanistan and Iraq seemed to belong to the same symbolic moment. Rather than some succesfully stage-managed US photograph, it is the improvised Snuff of Abu Ghraib which has come to represent the campaign in Iraq. Saddam's execution may have been intended as a moment of closure, but it signalled quite the opposite: the horrors continue. The images of Saddam being taunted by hooded figures horribly rhyme with the Abu Ghraib pictures.

With Saddam, it is as if the object of the Americans' desire receded every time they closed in upon it. The first time they caught him, a bewildered old man cowering in a hole in the ground, the very radicality of the desublimation counted against the Americans perhaps even more than against Saddam himself: surely this could not be the personification of Evil that the war had been waged against? In this case, Saddam was too dehumanised to serve as the proper object of avenging American justice. But the execution produced the opposite effect: it did what the spectacle of executions cannot fail to, it humanised Saddam, all the more effectively because of his stoic demeanour in the face of the taunts of his tormentors.

After the end, again

The discussion of post-apocalypse culture continues, with contributions from Jodi . Owen , Larval Subjects and Rough Theory.

Jodi is sceptical about my claim that apocalyptic dread has receded from the popular unconscious. This may well be a difference between the UK and the US, although, as far as I am concerned, none of the examples Jodi provides convincingly make the case: as Jodi herself concedes, Apocalypto is not about apocalypse in the relevant sense, while the forthcoming Omega Man is itself a remake of a film from an earlier - in my view much more genuinely apocalypse-fixated - era. (Interestingly, incidentally, The Omega Man was already a remake of the 1964 The Last Man on Earth, starring Vincent Price.) That leaves Children of Men, which may well be apocalyptic - but, well, one radioactive swallow does not a nuclear winter make. Jodi is right that there is no British equivalent to the religious apocalypticism that features so prominently in American cultural life but this is less apocalyptic dread than apocalyptic ecstasy, a fevered anticipation of the Rapture.

The kind of apocalyptic dread I am referring to was in any case far too pervasive to be reduced to particular cultural artefacts; nor was it confined to religious groups. There were, of course, innumerable films, novels and songs which explicitly dealt with apocalypse of one kind or another, but the dread was so widespread, so deep-rooted, that it amounted to a psychic climate. The whole of postpunk was an expression of this climate, which in part accounts for the appeal to postpunk of Ballard, whose Atrocity Exhibition remains the best primer on Cold War psychopathology. Jeff Nuttall's indispensable Bomb Culture went so far as to claim that the impulse behind postwar popular culture in its entirety was the virtual presence of nuclear war.

During the 60s, 70s and 80s, dreams about nuclear annihilation were such a nightly routine that they were deemed unworthy of comment. I remember a period of a few years as a child when I would ritualistically watch the first few minutes of the news just to check that a nuclear war was not imminent. Such dread was not confined to the anxious or the neurotic; it was part of the background noise of the culture. It may well be the case that this type of dread remains a feature of everyday life in the USA; I think I can say with some confidence that it no longer is the case here. In fact, if you describe the level of fear that was taken for granted in the Cold War to British teenagers, they are likely to look at you askance.

Certainly, Sinthome's remarks - in particular, his claim that 'apocalyptic fantasies' are 'omnipresent' in American culture - suggest that apocalypse has retained its hold on the American unconscious. The key passage in Sinthome's post is the following, where, in an echo of similar claims by Fredric Jameson, he makes the case that apocalyptic fantasies mask disavowed utopian impulses:

- [C]ould not the omnipresence of apocalyptic fantasies in American culture be read as an indication that somehow we have "given way on our desire" or betrayed our desire at a fundamental social level? That is, these visions simultaneously allow us to satisfy our aggressive animosity towards existing social relations, while imagining an alternative (inevitably we always triumph in these scenerios, even if reduced to fundamentally primative living conditions... a fantasy in itself), while also not directly acknowledging our discontent with the conditions of capital (it is almost always some outside that destroys the system, not direct militant engagement).

Against, or perhaps alongside, Sinthome's 'hope that apocalyptic fantasies manifest a desire for something other than their explicit content', N Pepperell at Rough Theory suggests that 'we can understand Adorno’s work as an attempt to reflect seriously ... on the possibility that certain mass movements might genuinely desire to achieve what their fantasies express: destruction and death.' A complementary analysis might emphasise the fantasy of survivability, as Christopher Lasch did in The Minimal Self: Pyschic Survival in Troubled Times, a book which seems in many respects to be a relic of the final phase of the Cold War. Lasch's claim was that, in the face of neo-liberal economic 'reform' and multiple threats of catastrophe - ecological, military - the self had been stripped down into a protective core. Anything beyond brute survival had become an extravagance. This 'minimal self' makes it beyond the Cold War to the end of history, and I wonder if the popular cultural examples Sinthome gives aren't better read as survivalist, rather than apocalyptic, fantasies: Independence Day and Armageddon, for instance, strike me as quintessentially nineties films in which the emphasis is not upon the apocalypse but on the very quick restitution of 'ordinary' life. In both, the destruction by Special Effects of a few cities is speedily succeeded by the muscular and heroic defence of the soon resumed American way of life, a fantasy which ominously foreshadowed the Shock and Awe response to 9/11.

January 13, 2007

The damage is done

'We should acknowledge that our world is doomed, that it has no future;' Dominic writes in a fascinating post, 'but also that it is not the only possible world, that other worlds have been and will be.'

But if it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism, then it is precisely the thinkability of different worlds succeeding this one that is at issue. In terms of the current political imaginary, there is only this world, then nothing... Or there are n number of new worlds, but each is a different rendering of capitalism: none would be an alternative to capitalism. Capitalism would be the equivalent of Alvin Plantinga's transworld depravity: that which must occur in any possible world. China or Dubai already give us glimpses of other possible capitalist worlds, establishing, incidentally, that while there is no parliamentary democracy without capitalism, it is perfectly possible for there to be a capitalism without democracy.

In many ways, however, we have ceased to imagine the end of the world just as surely as we have lost our ability to imagine the end of capitalism. Oddly, apocalyptic dread - so omnipresent during the Cold War - seems to have been extirpated from the popular unconscious. The possibility of environmental catastrophe may well be entertained as a rational hypothesis, but it does not dominate our collective dreams in the way that the threat of nuclear annihilation once did.

Perhaps it is necessary to change the terms of the formula. If it is increasingly difficult to imagine alternatives to capitalism, that is because the world has already ended. In this condition of mors ontologica, the world goes on, but nothing new can ever happen; what remains is a mechanical permutation through options that have already been fixed.

Philip K Dick was of course the great poet of the intuition that the world had already ended in this sense. Ubik and A Scannder Darkly are seen through the eyes of the (existentially or physically) dead. The deteriorating world of Ubik is indeed a 'glimpse [into] the breakdown and dissolution back into nothingness', that Jodi put described in the original post which in part prompted Dominic's reflections. In A Scanner Darkly, death is defined in terms of an inability to act, a terrible stasis: "That's what it means to die, to not be able to stop looking at whatever's in front of you. ... You can only accept what's put there as it is."

What Dominic points to is a situation that is that is even more dire, where it is perfectly possible to act, but any action is now irrelevant. The time to act was in the past; the damage is done; all we can do is await consequences which can no longer be averted:

- at least one plausible model of climate change asserts that all the emissions needed to change the climate irrevocably have already been emitted, and the effects of this change are even now ineluctibly unfolding: we pass from tipping-point to tipping-point. HIV/AIDS has already killed millions across the world, making orphans of millions more. None of this can be undone, and there is no possible future world unmarked by these catastrophes. The future designated by the “unless”, the future hoped for by the Western environmentalists and NGO workers of the 80s and 90s, cannot now come to pass. It “has already ended, and we are persisting in its degrading memory” - how many of the narcissistic disorders of our culture can be attributed to this awareness?

Here, then, is one sense in which we are ghosts, impotently tilting at a world we can no longer affect.

It's worth pausing here to reflect that, in the debates over climate change, it is no longer the apocalyptic potential of current trends that is disputed; what is doubted is whether any effective action could be taken to deal with it. Questioned about whether they will give up flying in order to combat climate change, people will often respond that there is no point, because others will continue to fly: thus runs the fatalism of capitalist realism. If Dominic is correct, of course, then they are not fatalistic enough.

Jodi's intution that the 'world has already ended, and we are persisting in its degrading memory' serves as an apt epigraph for postmodernism (=late capitalism). The 'China brands' problem - 'who can name a Chinese brand?' - may well be another symptom of this secret apocalypse. Even China's massive transformation is not enough to change the basic palette of capitalism. All that remains is cloning and recombination.

January 12, 2007

Enjoyment and the Secret

Christopher Nolan's The Prestige is an enthralling study of doubles, doubling and duplicity. Its twinned themes are obsession and the Secret: the Secret as objet-a, that which inspires, but which can never satisfy, obsession.

The Prestige is set in the 1890s, when a gaslit age was being awakened to the power of electricity, and its sensibility belongs to an older era of simulacra; one in which, instead of seeking to unmask illusion, audiences succumbed to its power. The film is about stage magic, and its most insistent refrain is 'are you watching closely?' But in the theatre, it was not possible to watch too closely; moreover, as The Prestige reminds us, the audience of magic willingly submits to misdirection in order to be beguiled.

The 1890s was perhaps the most Gothic decade ever: Dracula, The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Time Machine, not to mention Heart of Darkness and The Interpretation of Dreams, were all written between 1890 and 1899. The film has a lovingly cultivated whiff of fin-de-siecle Wellsian Scientific Romance, with Nikola Tesla (David Bowie, ) the key - in more than one sense - to the plot's intrigues. As an examination of duplicity and the willing subordination to illusion, The Prestige is of course about the power of film and fiction to cast spells. Its own captivation depends upon keeping the question of its own generic status open: are we watching a simulation of 1890s narrative realism or have we - as some IMDB commenters complained without irony - been 'conned' into watching an SF film? The film's final irony concerns the fact that, to function as magic, genuine science must appear as an illusion.

The film takes its title from Victorian stage magical terminology, which divided the trick into three stages: the Pledge, in which an ordinary object is presented, the Turn, in which the object disappears or is transformed, and the Prestige, in which the object returns. Behind the empirical object, however, is the sublime object which makes the Prestige possible: the Secret. The Secret is the stage magician's holy grail - what the two rival magicians Borden (Christian Bale) and Angier (Hugh Jackman) are prepared to steal, kill and destroy themselves in order to possess. Professional betterment and wealth may be the ostensible goals driving Borden and Angier, but it is the sublime allure of the Secret which draws them to their doom.

The film warns us repeatedly that the Secret cannot be possessed. The Secret is Nothing, and enjoyment is inherently tantalising. Before we are privy to it, the Secret is only a mysterous nullity, a black box. But, once it is revealed, the Secret immediately devolves into mere facts, empirical happenstance, deprived of that 'extra something' which was its sublime substance. Concealment fascinates; revelation disappoints. Naturally, this holds for the Secrets of fiction and the film - the maguffins and moonstones that are the object-causes of the reader's and viewer's desire - as much as for the Secrets of magic.

As soon as the Secret is exposed, the trick no longer interests the audience. Yet the magician who has designed the trick does not possess the Secret; he only knows the facts. What makes him an artist (the conjuror of an illusion) as well as an artisan (the creator of machines) is his capacity for convening/ concealing the Secret for/ from an Other.

The Secret exists in the reciprocal interplay of the audience's enjoyment and that of the illusionist. The audience's enjoyment derives from its state of puzzlement together with its awareness that there is a subject who knows; in order to preserve this enjoyment, the audience must not acquire knowledge for itself. The illusionist's enjoyment, as Angier makes clear in his final speech, resides in his seeing the entranced face of the Other - in other words, it consists in his enjoyment of the other's enjoyment, and to preserve his enjoyment, the illustionist cannot disclose his Secret. While the Secret is kept, Angier tells Borden, it transforms the universe from a grubby charnel house governed by logical and factual enchainments into a unpredictable place glowing with mystery and wonder. In this sense, the Secret is a miracle, the means by which the universe becomes more than what it is ...

January 06, 2007

The Germ of a Curse

Is the second Fall post cursed?

I've fallen victim to some debilitating viral thing over the past few days. I hope to be back before too long.

|  |

Meanwhile, in the year that another film version of the Strugatskys' Roadside Picnic is promised, Ballardian's Simon Sellars draws my attention to this....

"Anomalous zones pose great danger to stalkers. Getting into an anomalous zone nearly always results in instant death. There is only one way to oppose such zones, that is to avoid them! A problem here is to detect an anomalous zone, for the majority of them are invisible and can be detected with special devices or by inconspicuous indications."

Well, Jameson did refer to the Zone as an 'ontological Chernobyl'....