September 27, 2005

Jessica Rylan Interview: Sometimes I do feel this psychic connection with machines…

[the following post is by Infinite Thought]

'Look into that world of automatons, that robot-world which still invokes the name and even the mercy of God in order to get itself going, and invokes the existence of the living so as to imitate that existence more perfectly than in nature.' – Luce Irigaray, 'The "Mechanics" of Fluids', This Sex Which Is Not One

'Machinery does not lose its use value as soon as it ceases to be capital….It does not at all follow that subsumption under the social relation of capital is the most appropriate and ultimate social relation of production for the application of machinery' – Marx, Grundrisse

The future masters of technology will have to be light-hearted and intelligent. The machine easily masters the grim and the dumb – Marshall McLuhan

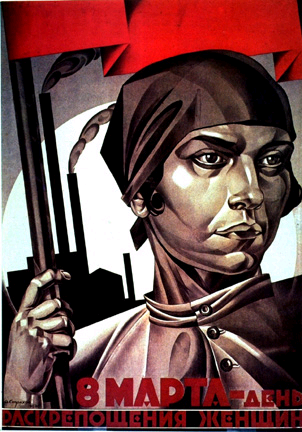

There's a scene in Dziga Vertov's 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera which combines footage of women doing a variety of different activities: sewing, cutting film (with Elizaveta Svilova, Vertov's wife and the film’s actual editor), counting on an abacus, joyfully making boxes, plugging connections into a telephone switchboard, packing cigarettes, typing, playing the piano, answering the phone, tapping out code, ringing a bell, applying lipstick. The cut-up footage speeds up to such a frenzy that at one point it becomes impossible to tell which activity is done for pleasure, and which for work. This is a vision, long before desktops, mobiles, call-centres and the invention of temp agencies, of the optimistic compatibility, perhaps even straightforward identification, of women with the boundless manifestations of technology and artifice….In February 1966, a group of Belgian women working in arms manufacture demand equal pay for equal work. Calling themselves "women machines", they go on strike, disrupting work for twelve weeks, behaving in the same way, they argued, 'as one carries out a war'...

Women have always been desired by the machine. It has needed them for their deftness, their smaller hands, their capacity to work quickly and, initially at least, to demand less for doing so. Rarely, of course, have women ever been on the side of construction (though Waterloo Bridge, the longest bridge in London, rebuilt by women during World War II, magnificently undermines the idea that women’s work is 'small-scale'). For women, typically, the machine dreams through them, as Sartre famously noted, inculcating just the right level of distraction for maximising performance - the erotic dreams a curious byproduct. The proliferation of typewriters and telephones in 1870s and 1880s, and the concomitant mechanisation of information, allowed women to compete for jobs they could easily do better than men. In other words, 'a large number of higher-salaried men with pens who added columns of four-digit numbers rapidly in their heads were replaced by lower-salaried office workers, many of them women, with machines' (Lisa Fine, The Souls of the Skyscraper).

Capital was and is increasingly feminised via its machines; high-rise gyno-capitalism literally making nothing, better, faster, as the circuits babble ceaselessly among themselves. A million data-entry workers sigh as the tips of fingernails clatter interminably; call centres trilling with the trained tones of treble-tone perfection; fembot recordings at stations instructing harried commuters where to be and when; on the other side of the divide, stitching, sewing, the sharing of space made easier by the capacity of women to almost vanish, despite their tendency to curve and accessorise. Far from possessing a deep-seated aversion to the unnatural, the contrived, the processed, women have forever shown their speedy capacity to adapt to and out-automate the machine, even as it uses and abuses them in turn.

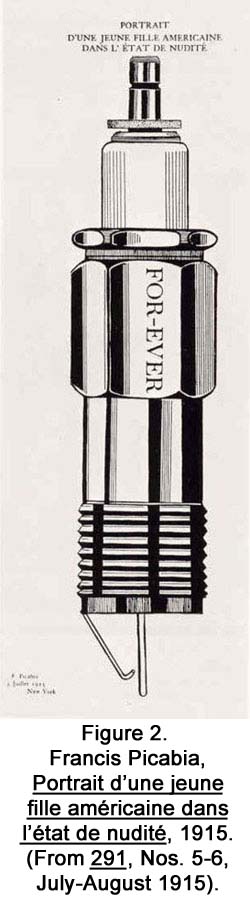

In one sense, we have always known this: that most machinic of data, communication, has always been the preserve of women, for better or worse (Kant’s Anthropology peevishly banishes 'the girls' to the other room for frivolous chatter, while the men discuss the important issues of the day). When silver screen superstar Hedy Lamarr co-invented a secret communication system in order to help the allies defeat the Germans in World War II, MGM kept this aspect of her life under wraps as incompatible with her 'star' image (even though she had already done her best to deflate the illusion, even at the very beginning of film idolatry - 'any girl can be glamorous. All she has to do is stand still and look stupid'). From mangles to washing machines, dictation to cryptography, espionage and war-time code-breaking, the manipulation and mechanisation of the feedback of machine, information and transmission has needed women often a lot more than it has needed men. As Gary Sauer-Thompson asks in a discussion of Picabia's Portrait d'une jeune fille americaine dans l'etat de nudite: 'If women…have become machines - in terms of the male gaze - then what has happened to men?'

What happens now, however, if we go beyond this? When communication becomes not something to understand and uncover but is the production of pure noise? When the machine, instead of dreaming through women, is created, maintained and exploited by them?

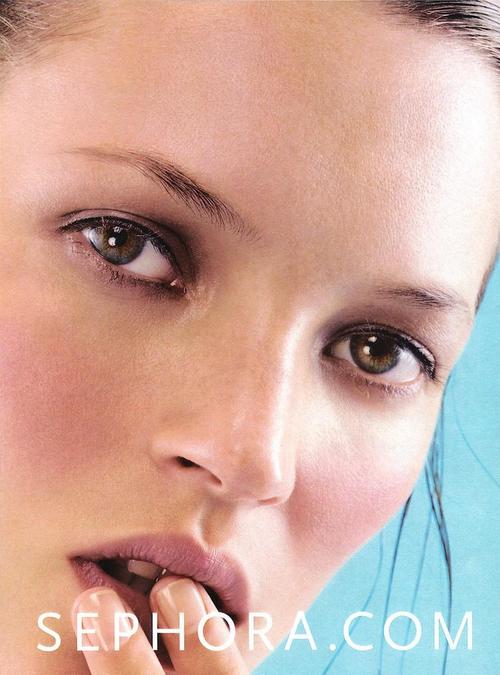

(from)

(from)

Jessica Rylan is the future of noise, in the way that men are the past of machines. Tall, slender, politely dressed, bespectacled…across a crowded clerks' office, Kafka's heart starts to pound. While the sirens of unpleasantness continue to seduce the male noise imaginary, Ms Rylan and her home-made synth-machines pose a delectable alternative: what if, instead of abject surrender to the hydraulic-pain of metal-tech, we forced the machine to speak… eloquently. But let's not be coy: there’s nothing nice about her noise – no concessions to the cute, the lo-fi, the cuddly or the pretty.

How does Rylan herself describe what she does? How does it fit with the rest of the Noise 'scene'? She has written on her website about the idea of 'personal noise', so I ask her to expand on this a little: 'So many people doing harsh noise, trying to live up to this Merzbow image. It seems really impersonal to me a lot of the time… Some people that do noise play really harsh. You’ll see them playing they’re like gritting their teeth, and playing this noise and it’s like, you don’t even enjoy your music. What are you doing? To me, it’s one thing if you’re doing art music, it’s totally abstracted and you don’t think about the emotional part, but when someone’s doing this loud music and it’s harsh, it should be about something.'

About something. There’s something perfectly poised about Rylan's fusing of form and content. She confesses her fondness for the organic all around her: 'I'm really interested in plants. That synth I’ve been playing, that personal synth is not very much like a plant but I have this other one I’ve built that I might start touring with, the natural synthesiser, and that one is more like a plant, more wavery sounds, and swishes, and there are time-frames that you kind of hear in the world, burbling water, whatever'. Replicating the organic via the inorganic, correcting the hippie idea that the best way to commune with nature is to be as close to it as possible (the familiar horror of beards, body odour, weed, letting it all 'hang out', the inelegance of the 'natural, comfortable' mob). On the contrary, the only way to even approach the artificiality of the natural is to outstrip and outdo its simulation, which Rylan does by plugging and unplugging her voice and body into the auto-circuits of an oneiric eroticism that weaves beguilingly amidst a series of disconcerting incongruities: 'Although it is characteristic of noise to recall us brutally to real life, the art of noise must not limit itself to imitative reproduction' (Luigi Russolo).

There’s no interest in nature in the noise scene, she says. 'This whole world, we’ve all gone indoors, we look on the internet, watch Tv, read books, watch movies, take drugs whatever. It’s all very interior, we don’t spend any time in the world. I mean, I did that for years, but there's all this stuff in the world that is so cool, that I feel like I didn’t pay attention to. It was really neat, we went to the museum today and there was this one Van Gogh painting, and looking at it, the whole thing just vibrated. And I was just got really choked up, it seemed like the painting was animated. It was moving and waving like grass would wave in the wind. That kind of thing to me is really interesting, like when sounds are animated in this really detailed way. I'm still working on that. That’s more like stuff to listen to at home. But live, it's different. You want to put on a show'.

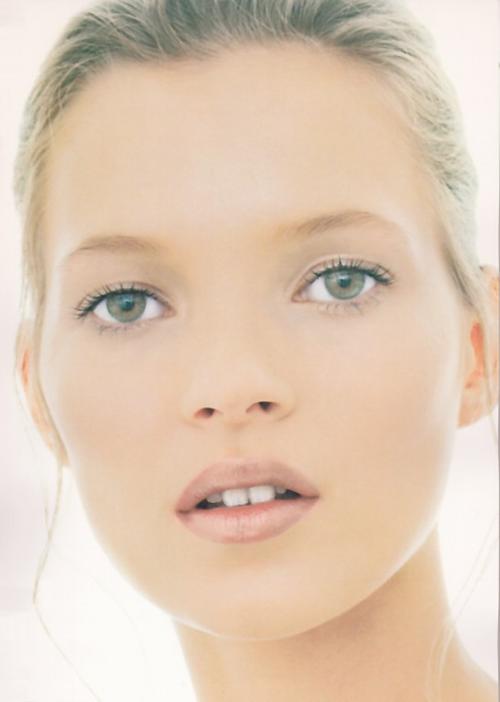

(from)

(from)

Ah, the show. Live, Rylan performs a combination of discomforting personal exposure (in the form of a capella songs played with unstinting directness towards the audience) and machinic communing with self-made analogue synthesisers feeding back to eternity fusing with ethereal, unholy vocals that haunt like cut-up fairy tales told by a sadistic aunt. I must admit the first time I saw the unaccompanied work I was taken aback, slightly appalled, even. Is that…noise? It’s just a girl reading poetry! But, in retrospect, without the disconcerting effect it produces, the rest of the show would perhaps lack a certain dimension, a certain creepy completeness. She says the British audiences respond very differently to this part of the show – at the gig the previous night, when she suggested she might do something 'quieter', the desire for 'more noise, more pain!' was shouted from the floor.

There's something deeply unusual about the way the analogue gets processed by the synths. Usually prized for its warmth, its authenticity, its richness, Rylan turns this fetishism of the vintage machine in to anti-warmth, the anti-real, a series of self-styled machines that cut up and disconnect time from itself in the present. Using analogue to out-mimic the effects of digital: 'I guess you think of warm drone when you say "analogue". The thing that is cool to me is that the analogue circuit is doing it in real time. The same thing as a tree branch shaking or something as the circuit electrically is vibrating and then that is going directly to the speaker and the speaker is vibrating, and so the circuit is vibrating in its own electrical world in the exact same way in the exact same time and to me that's really cool. If you use a computer and digital stuff that's like chopping it up and computing it, I just feel that computers operate in a time that we don't have access to. Because the instant for a computer is like four billion times a second, four million times a second. One ten-millionth of a second. What does that mean to us? I mean, we’re so slow in all our ways.' Rylan has commented before on her desire not to use any effects that mess with time (reverb, delay), but instead the machine messes with her and with itself, so you can no longer tell where the sound is coming from. In a way it no longer matters. What you see and hear is a series of deftly manipulated switches, wires and sockets attached to their creator, who circles the mechanical morass and herself emits sounds that feed back, away from and into the machine. The relation to the audience is deliberately ambiguous and highly structured – rather than the crowd-baiting outright aggression (however ironic) of most power electronics.

(from)

(from)

She confesses to a past infatuation with the work of Paul Virilio: 'I was reading all his books at that time and I was trying to do as much as I could as fast as I could, I was into changing everything as fast as I could. But he doesn’t even have an answer-machine, or a computer. Yet there’s this interview where he says how much he loves technology, I can totally relate to that. I really like that about him.' Her shows, while on the brief side now used to be even shorter, seven minutes or so, anti-indulgence personified. 'I did everything at once', she says. In many ways, this has always been the temptation of noise, to embrace the speed and brutality of the car, the machine, the 'love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness' of Marinetti's 1909 Futurist Manifesto, to live up to Russolo's demand to combine 'infinite variety of noises' using a thousand different machines (1913's Art of Noises). Whether or not the Futurists were openly or implicitly phallocratic (particularly compared to the prominence of women in the contemporaneous Soviet Suprematist movement) is perhaps secondary to the question of whether we should understand noise as the frenzied attempt to 'keep up' with machines, or with nature's most extreme sonic constructions: 'the rumble of thunder, the whistle of the wind, the roar of a waterfall, the gurgling of a brook, the rustling of leaves, the clatter of a trotting horse as it draws into the distance, the lurching jolts of a cart on pavings, and of the generous, solemn, white breathing of a nocturnal city; of all the noises made by wild and domestic animals, and of all those that can be made by the mouth of man without resorting to speaking or singing' (Russolo, 1913).

Rylan herself has had a Futurist-like transition from classicism to noise (Russolo again: 'We Futurists have deeply loved and enjoyed the harmonies of the great masters. For many years Beethoven and Wagner shook our nerves and hearts. Now we are satiated and we find far more enjoyment in the combination of the noises of trams, backfiring motors, carriages and bawling crowds than in rehearsing, for example, the "Eroica" or the "Pastoral"'). Her musical background is rather upright: 'I was in a classical children's choir, performing Mendelssohn, Bach at all these churches. It was wonderful. But then I had to go and destroy my voice by smoking all these cigarettes and screaming.' A little later, and not altogether surprisingly, she confesses her admiration for Jennifer Herrema (Royal Trux/RTX): 'she's like an albino or something, wearing a fur coat in the middle of summer. I think she’s so amazing. So trashy, but so cool'. I tell her the show put me in mind of Diamanda Galas, even though there are no obvious similarities in terms of voice or pitch. She seems pleased: 'I've never gotten that comparison, but I do really like her a lot!' There are certainly hints of a certain violent rock 'n' roll extremism to Rylan's shows which it seems has been tempered in the past couple of years:

The falling on the floor thing. Tell me about it. 'In the video (from 2002), I was at college and I fell on top of one of my professors, who that year won this MacArthur 'Genius' grant, for $500,000. He's like this genius improvising jazz musician and I just like took a dive at him. But he was cool, he just pushed me off. That was the weirdest show. But I felt good about it.' Personally, I can't think of a better way to pass a course. But things have calmed down for Ms Rylan of late. A bit.

'This year I started closing my eyes quite a lot this year, I don't know why. I just starting turning more inside. You have to be careful though. Playing with your back to the audience, it could be a position of vulnerability, but that position could also be like "fuck you, I don't care, I don't want to look at you". I've just started to try and think more about being on stage and how does it come across. All that spastic dancing…when I was playing to my friends they knew where I was coming from, but when it started being people I didn’t personally know coming to a show then they would just have these weird reactions to it. The worse one ever was at my house actually, at my loft…we were having this big party, there were like 200 people there, and so I was playing and some people came in but not that many. I was dancing all crazy, it was the best time I ever had at a show and I finished and I was so happy. And then nobody clapped and this one guy, who had been sitting on the floor got up and said "Thanks. That. Was. Very. Disturbing." And then everybody just walked out in single file. And I found out later on that the reason that only ten people had come into the space was because the people in the doorway just got stuck, deer in headlights style, afraid and couldn’t come in or something. And after that I was like "what am I doing?" That’s not what I want to communicate at all!'

So, how to avoid the blood draining from the faces of your unsuspecting audience? 'My relation to the audience has been changing. For a long time most of the shows we do are like really small, just thirty people or something. We usually play on the floor, with everyone right around you, it's more intimate. I really like that but I'm also really starting to think about…playing on the floor has become an ego thing…when there's more people at the show and you play on the floor they just can't see you….I don't want to play as loud as everyone else, but I think they turned it up louder last night. Working with feedback is tricky because sometimes it'll just get too loud and messed up. I’ve been moving on to the stage and off the floor. I had been playing on the floor for a long time. It’s like this punk rock idea like "we don’t want to have a separation between the audience and the musicians" and that’s awesome, but it's like, they paid money to see you play music! You want to put on a good show, people want to see. And it just especially sucks for shorter girls.'

Ah, Jessica! You stand on stage so girls like me can see you. It's impossible not to fall for that, but in many ways it exemplifies the careful thought involved in every aspect of her work: music, the show, the performance, the equipment. No slap-dash, jumbled-together mix of a misplaced genius-complex and self-indulgence here – go home off-the-cuff (or, ahem, wrist)-boys….

(from)

(from)

She speaks of her desire to have silence between bands at noise gigs, rather than loud pop music (as indeed happened just before Sutcliffe Jugend with a Strokes track). Purification? Timing? I think it's more a question of structure, of locating one performance amongst the others, creating a proper production. This tallies with her recent attitude towards structure in her own work:

'I used to do more improv things that were just kind of like a mess and just like whatever was, happened. But then I started writing songs and at a certain point I was like, how do I write songs with noise? So I tried to do that, which was tricky. A lot of the harsh noise bands, none of them have songs, it’s all improv, and with power electronics, they’ll have lyrics and the sounds they're going to use on certain parts but also like an open structure. That to me is the most attractive, because it’s a recognisable song, but you can also improvise. I like the idea of being very focused. I want it to be enough of a song that you could get into it, but also enough unpredictability that you really have to focus on it.'

Certainly, unpredictable effects seem to follow Rylan around - 'The first song I played last night when I went on tour in the US in February I played fourteen times in a row which somehow worked really well, and it doesn't work any more. Which is really weird because it was actually a love spell. It's called "casting a spell", and I was trying to get someone to fall in love with me. I thought if I keep doing it it'll work. But it didn't work on the person I wanted it to work on and I'm glad it didn't, in fact, I realise it would have been bad news if this person had fallen in love with me and then it seemed like it worked on some other people that I didn't want it to work on. But now my heart isn't really in that song, and it's really strange but the last few times I played it in the US, it was a total disaster. My mind and the synthesiser don't get along on this one. Sometimes I do feel this psychic connection with machines'.

You insist that there is something a machine cannot do. If you tell me precisely what it is a machine cannot do, then I can always make a machine which will do just that - John von Neumann

Where now? After a summer of extensive touring, Rylan could probably do with some time to reflect. 'Who knows what the future will be. But to be honest, I want to move out of the noise scene, although I really like it. I enjoy going to noise shows, I enjoy harsh noise but harsh noise is very self-limiting because it's only certain people that want to listen to that all the time, especially at those super loud volumes. There are certain things I wish I had more control over in what I'm doing. I did that same song in Leeds and it was just amazing, it was like this dream come true, but then the other two times I did it on this tour it was ok, but not quite at that level so you know it’s like, what I'm trying to figure out is how to recreate the experience. But not get bored. Personally I've really been trying to thing of it more as pop music, or to try and approach it like that.'

Pop-noise! If there were ever someone capable of leading such a movement, she's sitting opposite me sipping white wine in Soho while rubbish-collecting machines purr outside. But tell me more, who do you rate?

'I really like Kites and Prurient. With Kites – we have this real back and forth. We both build some of our stuff, analogue things. I really like his stuff a lot. But right now, this is terrible to say, Joanna Newsom. Everybody hates Joanna Newsom but folk, harps, high weird voice. I'm really into new folk. In the States, there's definitely a connection between the noise scene and that, or some parts of the noise scene and that kind of folk.'

Folk-noise! We talk a little bit about neo-folk and the quite, er, intriguing way this has emerged and mutated in Europe. It doesn't quite share the same complex ideological overtones in the US, apparently: 'In the US it’s kinda hippie, which I'm not as much into. But I like more traditional folk music. Because I feel that noise is a form of folk music. It's very grassroots. The thing about noise shows is a lot of the time that half the people in the audience also play. Which in a way is awesome and in another way is frustrating. We need more fans! I love that grassroots things, but there are things I think could also go to a broader audience. I hope it happens, because I think people could relate to it. It's amazing, like Merzbow, is kind of like a household name, almost. For any self-respecting hipster, they have one record or something. Even Wolf Eyes, who would've had thought that they would be as popular as they are now five years ago?’

We discuss the difference between the US, Japan and Britain with regard to noise. She speaks a little about Providence, the No Fun festival and Load Records: 'The whole Providence scene, it was a really noisy situation, and it's just grown. It was a lot of places like the Foundry, but worse. Concrete rooms, like super-reverberant, bad PAs, just gross. That's fun but...then, what is Noise? Is it like catharsis, something you have to go through, you have to face bad things in your life that you don't want to deal with and this is the way you deal with it? I don't even know anymore. I'm so used to listening to noise that it just doesn’t seem that extreme to me.' Nor, it turns out, does extreme pop music: 'Honestly, when I'm at home I listen to easy-listening music. Claudine Longet, in particular. She went crazy and killed her boyfriend, she was awesome. I'm really into melodies.'

from)

from)

So, folk-pop-noise project in mind, what else could the scene do with changing? 'The noise scene traditionally has been very interested in limited editions, fancy packaging, super fetish of the object. Which is interesting. I do think if you’re putting out a recording it’s really important to focus on it, think about the art and so on, maybe have a booklet come with it. But then you wonder, who is going to listen to all these records? That's the thing in the US now, everyone is putting out CD-R after CD-R all the time. You go to a show and you come home with like 6 or ten CD-Rs. When I was on tour with John Wiese, that was the worst. People just gave him stuff everywhere. Wherever he went, however much merchandise he sold, he left with three times as much. He was mailing stuff home all the time. But he only listens to 7 inches! Like that Merzbox…who has time to listen to that? People make all these limited releases just to trade them for other limited releases. I feel like there's a real pressure to release lot of stuff in the noise scene. It's like free jazz, improv music, putting stuff out all the time. I want to do less!'

Doing less might prove difficult. Rylan has recently received a Penny McCall grant for her work: 'I totally couldn't believe it. I had quit my job just before that, and then three days later I got the grant. This year I keep going on tour. I don't really have time to get a job! But I got to start doing something, some temp work or I've got to start selling some more synthesisers. I've sold four instruments this year. If I could just do one a month then I'll be ok'. She has also just received a post at MIT: 'I'm going to be a research associate at the centre for advanced visual studies. I’m going to get undergraduate interns to help me. I'm totally psyched.'

We discuss the potential risks of pursuing an academic career. 'When people get academic backing, that can become more important than their work. My dream is to be recognised in the academy and do more pop music, but I do feel very suspicious of academic music. It has two major traps it falls into. Either it has principles above response, like serialist composition, which nobody really likes. There's no point in making a record that no one wants to listen to, but then on the hand, all that polite applauding, yet total lack of rigour.'

'It's nice if you can rely on your equipment,' she says, before we stop to go and find some cigarettes. 'I know how to deal with my own equipment'. She's not wrong.

September 25, 2005

The gaze of the object

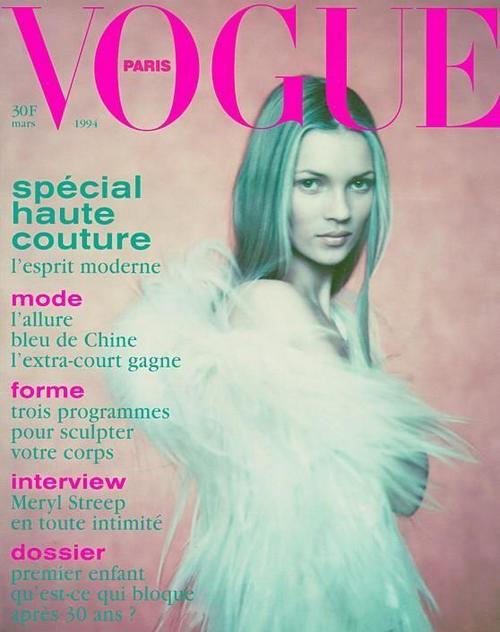

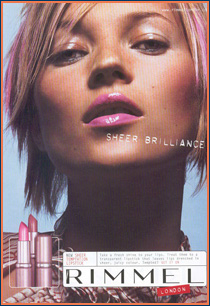

Well, the Kate Moss post I had promised and planned has been somewhat overtaken by events, but it's worth observing that the affair has brought forth a near-inventory of Lacanian themes.

The politics of enjoyment

The 'scandal', such as it is, clearly centres upon enjoyment: she has it, whereas 'we' - the interpellated subjects of the tabloid stories - are denied it. The British tabloid press has long understood the appeal of stories that play upon readers' resentment of Those Others who Enjoy (such stories are especially popular if the Enjoyment is seen to be at 'our' expense). The fantasy space that the lurid 'revelations' about lesbian orgies and 'fist-sized' balls of intoxicants opens up is that of an impossible, obscene, total enjoyment, an enjoyment which is only possible for Others (there are innumerable, supposedly contingent, reasons why we don't have access to Total Enjoyment, but they, they revel in it...) At a certain point, the moral condemnation of obscene luxury inevitably gives way to an acknowledgement that Total Enjoyment was not, in fact, possible, as 'irresponsible hedonism' becomes 'My Cocaine Hell'. The resentment of enjoyment is only sated once this final stage is reached, and it is satisfied that the enjoyment was not there to be had in the first place.

The big Other must not see all

There can be no-one who was shocked or even slightly surprised by the 'revelations' about Moss. Model takes cocaine... Next....

But we will be missing one of the lessons that the Moss affair has to teach if we simply sigh and move on, since nothing could more clearly exemplify how the the big Other functions in contemporary culture than the way in which Moss has been treated. Zizek has tirelessly insisted that we are liable to overlook the importance of the enormous difference between what is known universally (but secretly) and what is known officially. Terrible consequences always ensue once unacknowledged, obscene popular knowledge crosses over into the official culture. The big Other resides in the distinction between our all knowing something and it being publicly acknowledged, so when something that was once universally known is actually publicly 'revealed', the big Other must act. Or, better (given that the big Other doesn't exist, except as a retrospeculative fiction), officials feel that they must act on the big Other's behalf. As a perfect example of the latter phenomenon, witness the now almost completely discredited Ian Blair's ludicrous pronouncements about the Met considering action against Moss because of 'the possible effect on impressionable young people'. 'Impressionable young people' is of course one of the names of the big Other, one of whose crucial features is that it cannot know all. We might all know that models and celebrities routinely use class A drugs, but the big Other remains does not know. Those who rightly condemn Blair's intervention on the grounds that his stance implies that it was perfectly acceptable for Moss to snort cocaine anywhere except on the front pages of the tabloids must at the same time recognize that it is not the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police who has invented this bizarre situation: PR, advertising, the judicial system, politics, all depend on the highly artificial but routinely functional distinction between obscene and official knowlege. What Deleuze calls an 'incorporeal transformation' happens when events are reported in the press: the exact same occurrence becomes something of quite another nature.

The gaze of the object

My original topic, what I wanted to address before the scandal broke, was Moss's appeal. In what does it reside? A useful article in the Guardian earlier this year by Joanna Briscoe provides some clues. 'Women - perhaps even more than men - are intrigued' by Moss, Briscoe observes. Part of the attraction for women is the very 'naughtiness' that now sees her castigated (Moss 'manages to embrace the middle ground between self-destruction and steely control'), part is the whiff of the vernacular that no amount of cosmetics and lighting can extirpate from her features. Briscoe writes that Moss's 'paradoxical, multi-faceted appeal means that in the post-Benetton age, the faintly Asian cast of Moss's features translates into internationally comprehensible beauty, yet she is deeply English, to a degree that makes the icons of the 60s - Jagger, Twiggy, Faithfull - her only true antecedents, for all the posturing of Britpop. While contemporaries such as Kate Beckinsale or Minnie Driver undergo LA makeovers to secure global appeal, Moss trails the whiff of the Croydon comp, of Primrose Hill hedonism, of NHS teeth and pure, dirty London.'

Yes, Moss certainly has an ineradicable flavour of the quotidian about her, but that only deepens the mystery of her appeal. What is it that makes her more than just an ordinary London woman with unusual looks?

The model's task is to transform herself into images of the Sublime, to attain what Lacan calls the 'dignity of the Thing'. Now more than ever, the Sublime cannot be confused with the Ideal. Once it may have been possible to produce a sustainable image of the Ideal by covering up, maintaining a certain distance, but the intrusive nature of contemporary media make Idealization impossible; it isn't long before a photograph or an ex-lover appear to shatter the illusion. Moss's allure has not therefore depended on cultivating an impossible inviolability; on the contrary, as Briscoe writes, she is 'more often snapped fag in hand, screwing up pisshole eyes to take a drag on a London street, than posing on a red carpet'. The drugs stories might have destroyed her career, but they have had little impact on her allure. That's because Moss has managed to capture the inherently elusive qualities of the objet petit a itself, that which can never be possessed or caught. The important thing to remember, however, is that the object petit a is transcendentally, rather than empirically, inaccessible (much as we fantasize that the blocks to attaining the object are always merely contigent, 'if only X or Y had not happened, I would really have had it'). Moss's photographs manage to suggest that, even if you 'had' her sexually, that would not be 'it', there would still be something in her that will always lie beyond reach, no matter what.

Perhaps this is part of the reason why Moss has never been a Lad's favourite. The melancholy of Lads' relationship to pornography consists in its duped literalism - 'what I really want from women is their image, and what I really want from their image is to ejaculate', therefore I might as well wank over pictures. What this misses is the fact that there is no 'thing' that is 'really wanted'.

How a model looks is not even half the story; how she looks at the camera is where her artistry lies. The art of so-called glamour modelling consists not so much in entrancing the male eye so much as placating the male ego. That is why such photography has little to do with the dizzying sorcery of glamour (to 'glamour' originally meant to cast a spell on men, often to make them impotent) and trades instead on girl next-door homeliness, the slightly tantalizing appeal of the nearly-available. Crucially, the models' come hither looks are designed to make the male viewer feel desirable. (Hence Zizek's point that it is the users of pornography who are its real objects; the subjects are those who stir and manipulate desire, the actors and models themselves.)

I suspect that Moss is so appealing to women largely because she refuses to give that look. She is not there to make the viewer of her image feel comfortable, still less desirable or interesting. The glamour model either looks to camera smoulderingly or gives the impression of being demurely caught unawares. Moss does neither. She always radiates an easy awareness that she is being photographed, but doesn't seem especially interested in who is seeing her or the fact that she is seen. Her particular art is the cultivation of a look to camera that verges on the disdainful and the contemptuous, but never amounts to outright confrontation. It is almost as if she is fully aware of the camera (and therefore of us) but that, even when she looks directly at 'us', she looks through us, past us, fixating on something just over our shoulders. The challenge this poses is no longer the shock of the object talking, as it was with Grace Jones, because Moss, famously, does not speak.

In Moss's case, not speaking does not connote a failure to be a subject. No: it connotes a confident embracing of the role of the object. Moss doesn't talk back, she looks back, confirming the validity of Lacan's dictum that the gaze is on the side of the object. Lacan was referring to that uncanny sense that objects watch us (the converse of the fact that the petit objet a is a screen for our projections is the sense that beyond the screens, the Real looks back, acquiring all the animation that we have lost). Moss's gaze suggests that it is not the empowerment of the subject that is the real goal we pursue, but the Sublime serenity of objecthood. To be pored over, stared at, and to look back, not in anger, but with something approaching indifference ..... what could be better than that?

September 21, 2005

Unhomesickness

Pleasingly, there's very little about Ghost Box that's dark, but plenty that's unsettling. Off-kilter bucolic, drenched in an over-exposed post-psychedelic sun, Ghost Box recordings are uneasy listening to the letter. If nostalgia famously means ‘homesickness’, then Ghost Box sound is about uhomesickness, about the uncanny spectres entering the domestic environment through the cathode ray tube. At one level, the Ghost Box is television itself; or a television that has disappeared, itself become a ghost, a conduit to the Other Side, now only remembered by those of us of a certain age.

The affect produced by Ghost Box's releases (sound AND images, the latter absolutely integral) are the direct inverse of irritating PoMo citation-blitz. The mark of the postmodern is the extirpation of the uncanny, the replacing of the unheimlich tingle of unknowingness with a cocksure knowingness and hyper-awareness. Ghost Box, by contrast, is a conspiracy of the half-forgotten , the poorly remembered and the confabulated. Listening to sample-based sonic genres like jungle and (the pre-banal) hip-hop you typically found yourself experiencing déjà vudu, in which a familiar sound, estranged by sampling, nagged just beyond recognizability. Ghost Box releases conjure a sense of artificial déjà vu, where you are duped into thinking that what you are hearing has its origin somewhere in the late 60s or early 70s. Not false, but simulated, memory. The spectres in Ghost Box's hauntology are the lost contexts which, we imagine, must have prompted the sounds we are hearing; lost programmes, uncomissioned series, pilots that were never followed-up.

Belbury Poly, The Focus Group, Eric Zann --- names from an alternative 70s that never ended, a digitally-reconstructed world in which analogue rules forever, a time-scrambled Moorcockian near-past: Moogpunk. All three explore a sonic continuum which stretches from the quirkily cheery to the insinuatingly sinister. If there are precursors in Pop, they are at the edge of the genre: Eno’s On Land, Ultramarine’s Every Man and Woman is a Star. The more obvious predecessors, though, lie in ‘functional music’, sounds designed to hover at the edge of perceptibility not to hog centre-stage: signature tunes, incidental music, music that is instantly recognizable but whose authors, more often (self-)styled as technicians rather than artists, remain anonymous. The Radiophonic Workshop (whose one ‘star’, Delia Derbyshire, became known only recently) would be the obvious template. For this is sound which offers itself as a series of part-objects, supplements, a collector's kit for a collection that can never be complete.

As Kodwo established in More Brilliant than the Sun, cover designs are integral to sonic fictions. Too often the art in Art Pop is forgotten: the 70s was the most visual of Pop decades (it's not accident that Ferry trained as an artist, for example). The Concept realises itself in the space between the sound and the cover art. Cover art transforms mere music into a context by ensuring that the sound doesn’t coincide with itself. Its presence is subtracted, it becomes a sign, a revenant; which is to say, a ghost. You don’t need to consult the website (though, naturally, you should) to recognise that Ghost Box is implicated in a web of pulp esoteria: Children of the Stones, New English Library paperbacks, Hammer films, Lovecraft, Lewis, The Tomorrow People, Blackwood, Timeslip ... It's good to see that I'm not the only one to be continually in search of Things that would spook me as they did...

September 13, 2005

A world of dread and fear

'You couldn't sleep. You had to work.

Always light.

Head against the window, sun coming up -

The troops were gathering on the street below him. The Red Guard in good voice:

SCAB, SCAB, SCAB -

The dawn chorus of the Socialist Republic of South Yorkshire.

Another cup of coffee. Another aspirin - ' (7)

David Peace's GB84 is typed in prose as stark and unforgiving as motorway service station strip-lights.

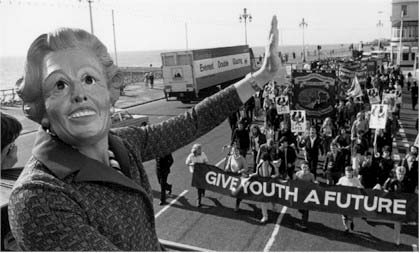

The harsh expressionist realism Peace honed over the course of the four books of the Red Riding Quartet is perfect for handling GB84's subject matter, the events of the 1984-85 Miners' Strike. The Quartet counted forward - 1974 --- 1977 --- 1980 ---- 1983 --- as if it is was approaching but would never reach the fateful date that will provide the title of GB84. From here we count backwards; GB84 'is actually the last of an inverse post-war trilogy which will include UKDK, a novel about the plot to overthrow Wilson and the subsequent rise of Thatcher and another book, possibly about the Atlee Govt.' From Gothic Crime to Political Gothic...

The fiercely partisan novel ends with the incantation: 'the Year is Zero'. But 1985, when both the Strike and the book end, was very far from being a year of beginning or of possibilities for the novel's 'us', (in fact, the very existence of that 'us', the collective proletarian subject, is itself in question by then. At the same time, however, this is the first of Peace's novels in which the possibility of any sort of group-subject is raised. More typically, his characters are solipsistically alone, connected only by violence, their only shared project dissimulation). On the contrary, it was a year of catastrophic defeat, the scale of which would not become apparent for a decade or more. (Perhaps it was only the election of New Labour twelve years later that the defeat was both registered and finally secured.)

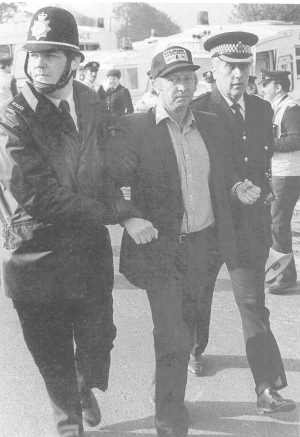

We now know - although this cannot enter into the present tension of the novel - that the strike was about a failed Proletarianization. After the events the novel describes, what awaited was fragmentation, new opportunities for the few, unemployment and underemployment for the majority. The technique of flying picketing that Scargill had pioneered so successfully in the late sixties and early seventies (and which had contributed to the humiliation and collapse of the Heath government) was combatted by a comprehensive range of strategies (including a highly-organized counter-subversion operation run by MI5) that were designed while the Tories were still in opposition. The aim was to fragment miners' solidarity and to prevent support from sympathetic workers in other industries. In this, the creation of the Working Miners Committee and the Union of Democratic Mineworkers would prove crucial. The deterritorialization of capital - its transmutation into 'messages which pass instantaneously from one nodal point to another across the former globe, the former material world' (Jameson) - was not to be met by a complementary deterritorialization of labour. Miners were inveigled into identifying with their own terrirory rather than with the industry as a whole; hence the return to work of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire miners, who believed that they were safeguarding their future but in a satisfying irony found themselves no better off than miners from any other coalfield. Within a decade, the industry would be all but closed down in Britain, with members of the UDM no more likely to be in employment than those of the NUM.

Yes, we know all this, now. But Peace restores drama by excluding any of the knowledge hindsights brings. The events come at you as if they were happening for the first time, and without the emollient shield of an omniscient authorial voice. As Joseph Brooker identifies in a lengthy piece on GB84 in the current issue of Radical Philosophy, the novel is bereft of any mediating meta-language. The tragic quality the novel possesses even in its earliest scenes comes courtesy of the knowledge we, the readers, bring - but which is, naturally, is denied to the protagonists - of the eventual course that the strike will take.

Counterfactuals are largely the preserve of the reactionary Right, and Peace refuses the temptation to change the facts. He writes his retro-speculative fiction in the spaces between the recorded facts, extrapolating, inferring, guessing. Yet the question the reader cannot help but pose is: what would have happened if the miners had won? (A question that has added piquancy since subsequent revelations have shown that the government was much closer to defeat than was ever suspected at the time.) The narrative in which the Strike is now embedded - the only narrative in town, the story of Global Capital - has it that it was part of a receding ebb tide of organized working class insurgency. Defeat was Inevitable, written into the Historical passage from Fordism to post-Fordism. The hard Left are outflanked, fighting under the banner of the Past for 'the history of the Miner. The tradition of the Miner. The legacies of their fathers and their fathers' fathers -' (7)

But such a narrativization is question-begging, since the very credibility of this story relies upon the events of the Strike unfolding as they did. What if they hadn't? Under the aspect of eternity, everything is inevitable and we are all Spinozists. But life has to be lived 'forward', making us Sartreans. Reading the book now inevitably dramatizes the tension between these two positions, between knowing that everything has already happened and acting as if it hasn't.

A gang of doppelgangers, near-duplicates, haunt the pages of GB84, this 'fiction based upon a fact'. Peace writes an occulted history of the present by constructing a simulation of the near-past. The dramatis personae do not bear the names of their real-life counterparts, and sometimes don't have names at all, merely titles designating their stuctural role: The President, The Chairman, The Minister. Sometimes, real world names are slightly altered; in GB84 the NUM's Chief Executive Roger Windsor becomes the hapless Terry Winters. The relationship of these simulations to their real-life counterparts is complex. The President is not Scargill. But he's not not Scargill. No doubt Peace changed the names in part to avoid legal action, but in an odd way the extra imaginative latitude he is granted by not being compelled into fidelity to actual biography gives the characters more reality. He is able to get inside their heads in a way that would not be possible with actual biographical individuals.

The most controversial characterization is that of Stephen Sweet, the professional strikebreaker based on Thatcher's right hand man throughout the Strike, David Hart. Hart was the driving force behind the creation of the Working Miners' Committee and the UDM. In the novel, Sweet is seen planning the crucial battle between police and pickets at the coking plant, Orgreave. (Devoting all its resources to Orgreave is now regarded as a major strategic error by the NUM.) Sweet is referred to throughout the novel as 'The Jew'. Although this designation remains uncomfortable - as it is intended to be, Peace has said - suspicions of anti-semitism are immediately rebutted by any sort of close reading of the novel. Everything we see of Sweet is focalized through his chauffeur-factotum, Neil Fontaine. (This distancing is significant, since Sweet's pomposity and grandiosity strike a slightly unconvincing note. It is almost as if Peace is unable to find the sympathy necessary for a convincing characterisation. On the other hand, perhaps Hart was the faintly absurd figure that Peace paints his fictional counterpart as. Peace does not make the mistake of portraying Sweet as a self-consciously evil figure; on the contrary, Sweet sees his efforts in a messianic light.)

Fontaine, presumably a co-opted member of the working class who has worked for the security services, is a blank slate of a figure, a man reduced to function (he is doubled in the novel by David Johnson, The Mechanic, who becomes an antagonist but who was clearly an ally in the past). It is Fontaine, a man with Right-wing affiliations and connections but few passions, who will never stop seeing Sweet as 'The Jew'. That description foreground the provisional nature of the political alliance that Thatcher built: somehow, the Thatcher programme allowed fascists to consort with Jews, nationalists to find common cause with the agents of Multinational capitalism.

Fontaine is also the connecting link between the overt and the covert counter-'subversion' operations undertaken by the State in GB84. It is in the unraveling of the MI5's role in proceedings that leads Peace into the territory of endemic corruption and betrayal that he staked out so viscerally in the Red Riding Quartet. Unusually for Peace, so skilled at putting himself (and therefore us) into the shoes of irredeemably corrupt power puppets, there is no major character in GB84 who is a policeman. But there are State functionaries: Fontaine, Johnson, but, most vividly, Malcolm Morris, a man whose role is to be a shadow, a cipher, an expert phone-tapper who, in a Francis Baconoid delirium, fancies that his ears are always bleeding...

In GB84, MI5 are the key players in organizing Terry Winters' spectacularly ill-judged trip to Libya. Who can forget the television images of Roger Windsor kissing Gadaffi in his tent? Winters/ Windsor's Libyan visit - only a few months after the policewoman Yvonne Fletcher had been killed by Libyan agents - proved an important, perhaps decisive, PR defeat for the NUM. (The actual role of Libya in the Strike was somewhat different: the Thatcher government had illicitly increased oil imports from the supposedly outlawed regime so as to see off the threat of power cuts.) Peace deliberately leaves the degree of Windsor/ Winters' collusion with the security services unclear. He wanted the novel to be a 'mess', like the Strike itself.

The doubling of historical fact with Peace's version of it is internal to the novel's own structure, whose main fictional thread is cut through by a diary account of the Strike by two miners, Martin and Peter. Martin and Peter's accounts, rendered in the Yorkshire dialect Peace captures so ably, were 'not fictionalized', Peace has said. It is here that Scargill, Macgregor, Thatcher, McGahey and Heathfield appear in their own names. The first person accounts register the grim miseries of the Strike, as well as its comaraderie, forming a contrast with the skullduggery, the corruption and the high-level meetings of the novel's central narrative.

Peace says that he first puts himself into the past, and then imagines. It's like Method writing, or time travel. Peace has tried and tested tricks to get back. He uses jaundiced newsprint, books but most of all Pop - not the stuff he would have listened to himself, then, and has listened to ever since but the songs that, ubiquitous then, forgotten now, can function as audio-madeleines. Digging through the carboot sale detritus of 84 and 85 Pop, Peace finds a coded history of the Strike secreted beneath the dull sheen of thrownaway post-New Pop.GB84 begins with Nena's execrable '99 Red Balloons', which here becomes an apocalyptic carnival tune, bursting with all the hopes that will sag and bleed by the end of the novel's gruelling, long, long march. 'Two Tribes' soundtracks the next phase, the confrontation between police and miner (both this and the Nena song, of course, played upon Cold War anxieties when they were released. Another reminder, and there are many in this novel, that 1984 was a world away). The exhilaration and adrenalin of out and out confrontation, Us and Them, gives way to suspicion (who is with us, and who is against us?) 'Two Tribes - Must have heard that bloody song ten times a day now for weeks. Ought to make it National Anthem, said Sean.' (176) The songs that Peaces dredges up for the final phase of the Strike are 'Careless Whisper' ('guilty feet have got no rhythm') and, for the 84-85 winter that was cold, but not cold enough - the power cuts never come - Band Aid's 'Do They Know It's Christmas'. Characters speculate that Band Aid is a government-backed scheme to distract from the plight of the miners, and the line that Peace selects for sampling is, naturally, 'There's a world outside your window, and it's a world of dread and fear'.

Sampling is precisely the right term, since Pop, much more than literature, film or TV (Peace actively distrusts these latter two) provides Peace with a methodology for drilling his words into the repetitions and refrains that are his stock-in-trade. Repetition is a hallmark of Peace's style; he has famously remarked that the strike was intensely repetitive and that the prose whould reflect that. But in all of Peace's writing, repetition is what substitutes for both plot and character. His Crime novels make no attempt to interest readers in the intrigue and enigma of plots; the plot of GB84, meanwhile, is given in advance, a kind of readymade. And one strange quality of Peace's writing that is not immediately evident is that, although it is unusually intimate - reading his novels is always like rifling through someone else's most secret places - his characters lack what is usually called 'inner life'. They are identified less by a reflexive vitality than by death-drive repetitions, riffs, echoes, habit-forms.

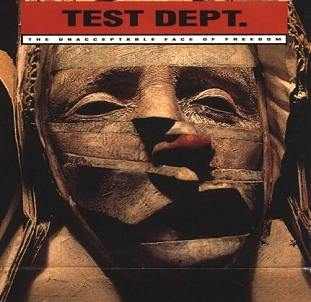

In GB84 the result is more poetic than most poetry; it is, naturally, a poetry stripped of all lyricism, a harshly dissonant word-music. Peace is a writer particulary attentive to sound: the unsleeping vigilance of State power is signified by the 'Click, Click' of the telephone tap , the massed ranks of the police by the Krk, Krk of boots and truncheons beaten against shields, both sounds repeated so much that they become background noise, part of the ambience of paranoia. The Telegraph review was right to observe that, 'At times, the novel feels like an eardrum buzz, the literary equivalent of late-1970s Northern bands such as Throbbing Gristle and Cabaret Voltaire.' It resembles even more closely the two great post-punk responses to the Strike: Mark Stewart's As the Veneer of Democracy Starts to Fade (Keith Leblanc also produced the single 'The Enemy Within') and Test Department's The Unacceptable Face of Freedom. Perhaps for this reason, Post-punk recedes as an explicit reference in GB84. It had been present in Nineteen Eighty Three in titles of sections of the novel: 'Miss the Girl' (The Creatures) and 'There are No Spectators' (The Pop Group). The tone for GB84 is in every sense set by the title of the last section of Nineteen Eighty Three: 'Total Eclipse of the Heart'.

Part of the reason that 1985 seemed like the worst year for Pop ever was that it was the beginning of the Restoration. Up to 1984, British popular and political culture was still a battleground. 1985 was the year of Live Aid, the beginning of a time of the fake consensus that is the cultural expression of Global Capital. If Live Aid was the non-event that happened, the Strike was the Event that didn't.

'Swords and shields. Sticks and stones. Horses and dogs. Blood and bones -

The armies of the dead awoken, arisen for one last battle.

The windscreen of the Granada lit by a massive explosion -

The road. The hedges. The trees -

Fire illuminating the night. The fog now smoke. Blue lights and red -

Terry shook Bill's arm. Shook it and shook it. Bill opened his eyes -

'Where are we?' shouted Terry. 'Where is this place?'

'The start and the end of it all,' said Bill. 'Brampton Bierlow. Cortonwood.'

'But what's going on?' screamed Terry Winters. 'What's happening? What is it?'

'It's the end of the world,' laughed Bill Reed. 'The end of all our worlds.' ' (320)

September 10, 2005

Getting rid of the poor

All the justified furore about the power elite using Katrina as a cover under which they can 'get rid of the poor' from New Orleans should be nuanced. We need to understand the way in which the desire to 'get rid of the poor' is a garbled utopian impulse which exposes one of capitalism's fundamental fantasies.

Why is it that the desire to eliminate poverty - which, presumably, we all share - inevitably becomes a desire to eliminate the poor? It is because, in capitalist ideology, poverty has to be thought of as an ethnic, rather than a social or economic, trait. The poor are those who are genetically destined to fail, those who lack 'middle-class skills' as the Herald and Tribune put it the other day (middle class skills here does not mean the skills possessed by middle class people, but the skill of being middle class). Populocide (or ethnocide) replaces socio-economic overhaul.

But this desire to eliminate the poor is also disingenuous in another way. The poor cannot be eliminated under capitalism - only airbrushed out of the picture, moved somewhere else. Naturally, however, this can never be admitted, since to do so would be to give up the fantasy that poverty is a contingent feature of capitalist societies rather than a structural requirement.

UPDATE: response by Lenin.

September 09, 2005

Patrick Hamilton on BBC2

UK readers: I would thoroughly recommend the BBC's adaptation of Patrick Hamilton's Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky, which starts tonight on BBC2. I manage to catch most of this when it was originally broadcast on BBC 4 earlier this year, and it's well worth a look.

September 06, 2005

Goodbye Robert Johnson, hello Robert Johnson Hotel and Casino Resort Complex

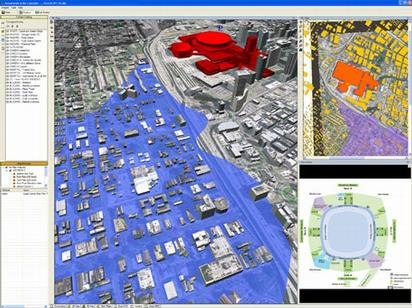

What could be clearer, as we watch New Orleans collapse, than that Jeter's world is ours?

The images of rotting urban infra- and social structure I wrote about a couple of days ago now find their correlates on the TV news, which increasingly resembles the most lurid of computer games. At the heartland of Jeter's version of cyberpunk are precisely the ex-urban spaces that some are predicting New Orleans will become. As Paul of the Boulder Anti-Apathy Cluster speculates in an excellent post: 'It's a terrifying notion to think about, but we must: the poor of New Orleans may have been deliberately dispossessed (and demonized as "looters") in order to make way for the rebuilding of New Orleans on the sterilized theme park terms of the rich. Goodbye Robert Johnson, hello Robert Johnson Hotel and Casino Resort Complex.' (Goodbye Robert Johnson, hello Robert Johnson Hotel.... The mess and stench of actual poverty must be photoshopped/ shipped out of the picture, to return as aestheticized decoration. In Jeter's LA, the rich adorn their luxury appartment blocks with Mumbling Junkie automata and mechanical rats.)

One reason that conspiracy theories don't cut it is that capitalism has terminated the long-term thinking which conspiracies depend upon. No more planning, only deliberate obsolescence, the improvised harnessing of natural disasters as a means of urban clearance. Everything is an opportunity. There's no catastrophe that can't be capitalized on.

Capital has an ambivalent relationship to the 'indeadted', the homo sacers which Global Capital both excludes and feeds upon. Or: global Capital imposes a state of constant ambivalence, sub-social interloping, hyper-precarity on whole populations that switch from exploitable labour to redundant ex-human resources at the click of a mouse. Dispossession as disconnection: and yet - and this is Jeter's riposte to all those Californian post-Marxist hymns to wired post-humanity - there is no connectedness without the disconnected. Disconnection is not so much exclusion as peripheralization, removal from the land of the living. In Noir you aren't even allowed to die if your debts aren't settled, and some of those most haunting scenes of the novel see the pathetically re-animated indeadted scouring through towers of toxic trash for the means of making someone else's living.

Every knows that 'our' indeabted - the black poor in America - are second-class citizens, or rather non-citizens. Everyone that is, apart from the Big Other, of course, and the rupturing of its ignorance accounts for the frission produced by Kanye West's now notorious traumatized outburst on TV. America's first response to any catastrophe, including those that afflict itself, is anodyne narrativization, the semiotic equivalent of the gloopy nutrient gel poured into the destroyed streets in Jeter's novel. Kanye's interruption of that drip feed of rousing/tranquillizing therapeutic babble - which, as Steven Shaviro summarises seeks to ‘explain’ how, even in the face of sadness and tragedy, life goes on and the USA continues to be the greatest nation on earth' - was the very definition of the inappropriate, and these are conditions in which, as Shaviro says, any fitting response to the media images will immediately be deemed 'hyperemotional'.

The innocynical sentimentality that Kanye disrupted is the hallmark of Late Capitalism, and this is where Jeter's novel strikes a false note. His 'villain', the DynaZauber executive, Harrisch, is a man devoid of all sentimentality, a corporaptor with unwavering reptillian eyes. Harrisch happily concedes that DZ is sublimely indifferent to any ethical constraints, its goal to reduce consumers to slavering junkie slaves. This makes him not only a somewhat unconvincing Sadean libertine but a man entirely without ideology. Ideology is always in part a rationalization, a justification, which presupposes the very discrepancy between motive and action that Harrisch's rapacity smooths over. Such clear-eyed, wanton exploitation is what Kant called radical evil. As Alenka Zupancic explains, radical evil 'refers, firstly, to the fact that our inclinations are the only determining causes of our actions and, secondly, to the fact that we have consented to our inclinations functioning as the only possible motives of our actions'. What makes this possible in Harrisch's case is the implausibly perfect convergence of his interests with those of the corporate monolith for whom he acts.

But is it conceivable, as Jeter's characterization of Harrisch suggests, that any corporate body, any social system, could actually present itself as radically Evil? It is no accident that no actual corporation has presented itself this way, particularly not now, where the most useless and destructive product cannot be retailed without spurious ethical benefits. It's tempting to say that even Nazism and Stalinism persuaded themselves that they were Good, but such a delusion, far from being a contingent, accidental feature of these regimes, was constitutive of the Evil they performed. The self-perception (self-deception) is structurally necesary. Self deception indeed: the role of ideology is not wielded by the rich and powerful to persuade others of their goodness. No: it is there to persuade them that their actions are noble.

September 05, 2005

More high-quality investigative reporting....

After waving a goodbye to the anti-humanist Loony Right, Sphaleotas exposes yet another plagiarism scandal...

September 02, 2005

Jeter's libidinal economics

A near-future world in which copyright violation is punishable by near-death? The premise upon which K W Jeter's novel Noir is based risks bathos and absurdity. As it happens, though, the sheer intensity of Jeter's detestation of copyright violators attains a certain sublimity, most notably when he describes the evisceration of a minor-level downloader. The kid has his spine and cortical matter removed and preserved to be later encased in speaker wire as a 'trophy', allowed just enough life to suffer indefinitely. As Steven Shaviro points out in Connected, or what it means to live in the network society (in which Jeter plays a central, if usually adversarial, role): 'What's remarkable about this section of Noir is not just the amazing conception of the punishment mechanism, a sadistic machine to rival the one described in Kafka's "In the Penal Colony." Even more startling is the gusto and gleeful exuberance of Jeter's prose as he describes the torture in loving, intricate detail, savouring it on page after page. Indeed this is the only place in this bleakly dystopian book that Jeter allows himself any sings of hope, satisfaction or pleasure.'

Jeter couldn't be more out of step with the cyber-Californian conviction that 'information wants to be free'. He sneers at such homilies, scorning them as 'a half-baked amalgam of late-Sixties summer of Love and Handouts, Diggerish free food in the Panhandle of Golden Gate Park, and Stalinist collectivization' . Jeter's hard-boiled prose radiates, in fact, a loathing for 'everything that flows', from the information networks that allow copyrighted material to be freely exchanged to the delocalizing and deterritorializing effects of global capital itself. This loathing reaches a delirial pitch in the climactic image of Noir, which sees downtown Seattle consumed by a fire-extinguishing nutrient gel. The gel contains the fire, but at the cost of de-individuating organisms, swallowing them into an orgiastic ocean in which the skin, the last boundary to 'ultimate connectivity' is sloughed off, and the obscenely replicating 'stuff of Life' is exposed in its true form(lessness).

It would be difficult to think of a more perfect image of what Baudrillard characterizes as 'the ‘proteinic’ era of networks, [...] the narcissistic and protean era of connections, contact, contiguity, feedback and generalized interface that goes with the universe of communication' than this seething slime. Not for nothing does Baudrillard describe the hyperconnected cybernetic system as obscene, and he would no doubt understand why, in the universe of Noir, the word 'connect' functions as a profanity, i.e. 'what the connect are you doing?', 'connect you, mother-connector'. In substituting 'connect' for 'fuck', Jeter forces us to reflect on what it is that made 'fuck' an obscenity in the first place. His implicit suggestion is that 'fuck' is a profanity because sex compromises the integrity of the organism, and such a compromise remains abominable, no matter how attractive it might also be.

The deadly lure of that which will erase all identity is of course the libidinal motor of Jeter's beloved film noir, at the heart of which is the sublime presence of the femme fatale, the Woman Thing. But the 'little death' that the sex-siren can offer is as nothing compared to the near-total annihilation of subjectivity promised by the connecting technologies of Jeter's twenty-first century. In Noir, it is as if the Thing - the primordial Real - can throw off its female avatar and emerge as a depersonalized, technological monstrosity.

'In Oedipus the King,' Alenka Zupancic writes, 'it is ... the Sphinx that plays the role of the femme fatale.' In Noir (and Oedipus Rex, as Zupancic observes, is the first Noir story), the femme fatale plays the role of the Sphinx. In Sophocles' play, the Sphinx is more than the harbinger of death: it is in the destroyer of the very possibility of identity, of individuality, itself. The plague that the Sphinx brings is the correlative of Oedipus's unwitting transgressions, because the destruction of his Father and the 'connnection' with his Mother threatens to return humanity to the condition of bacteria, which are indifferent to 'generational time' and therefore to organismic individuation. The Sphinx is what threatens to subsume humanity into what Anti-Oedipus calls 'the biocosmic memory that threatens to deluge all attempts at collectivity.'

In Noir, the Sphinx-figure borrows her most frequently-used name from the Aztec 'goddess of filthy things', Tlazolteol, and the novel's anti-hero, McNihil, encounters her via a kiss with an avatar who takes the femme fatale role of the 'ultimate barfly'. The 'ultimate barfly' is a Prowler, a human-simulator who roves the 'Wedge' (a delirial interzone somewhere between cyberspace and Leopold Bloom's Nighttown) to trawl for memories which she returns to her user via a flesh interface located in the tongue. McNihil describes her kiss as 'like a contact with a live battery'. Abandon all hope ye who enter here, Jeter warns, but he might as easily have written ye who enter her. McNihil's contact with the Tlazolteol-Thing is more than a brush with Death ('To have any encounter with Tlazolteol at all, to have seen her in my face the way you did and still be walking... you're a totally lucky bastard', the Prowler tells McNihil), it is indeed to travel 'beyond hope', to an 'End Zone' of pure fatality, the place that every letter is destined to reach, where those who 'have always been waiting for you' hang out.

'Different names, different forms. But always the Filth Deity - that's what the name means - the goddess of sexual impurity and deep, bad, annihilating sin. First a seductress, with no thought in her immaculate head other than connecting. Then comes her first destructive form, the one dedicated to gambling, risking and daring everything, including your own life. Then the redemptress, the form that can absorb and absolve human sin. That form can forgive sinners and remove all the world's corruption. It's not her last form. The last form is the hag with teeth of iron, the destroyer of pretty youths and all innocence. Like I said - everybody meets up with her eventually.'

You always know the Tlazolteol-Thing when you see her. Both she and the nutrient ocean-gel are images of a Deleuzoguattarian Capitalism that is, like the Sphinx, the 'condition of impossibility' for Oedipal subjectivity. For Deleuze-Guattari, Oedipus is simultaneously the denial and the expression of a Capitalism that, on the one hand, unpicks all identities, and on the other, is defined by its continual thwarting of final collapse into schizophrenia, Jeter's ultimate connectivity. Anti-Oedipus:

'And isn't that also what Oedipus, the fear of incest, is all about? If capitalism is the universal truth, it is so in the sense that makes the capitalism the negative of all social formations, it is the thing, the unnamable, the generalized decoding of all flows that reveals a contrario the secret of these formations, coding the flows, and even overcoding them, rather than letting anything escape coding.'

Intellectual property is at the bleeding edges of capitalism. At the same time as digital culture becomes increasingly difficult to protect, hitherto uncommodifiable entities - such as the genetic code of remote tribes - fall under corporate ownership. As Shaviro identifies, one benefit of Jeter's hardline stance on copyright is to make intellectual property not a technological, but a political and economic matter. Jeter, in fact, deals in libidinal economics, in the psychoanalytic dimensions of trade of every kind. Suffering, and the desire to cause suffering, are central to Jeter's theory of economics. Presenting a kind of Nietzschean Geneaology of Downloading, Jeter speculates that theft of intellectual property is more than a matter of saving money. Downloaders trade in copyright material because they resent creative people and want to destroy them. (They also hate themselves, since in an age of such draconian measures against copyright violation, to download is an act of self-destruction.) The desire to cause pain is present in owners as well as in those who steal, though. In his first sequel to Blade Runner, The Edge of the Human, Jeter solves one of the puzzles of the original film by explaining why the replicants were made increasingly sentient. As Tyrell's niece, Sarah, explains to Deckard:

'Why should the off-world colonists want troublesome, humanlike slaves rather than nice, efficient machines? It's simple. Machines don't suffer. They aren't capable of it. A machine doesn't know when it's being raped. There's no power relationship between you and a machine. ... For the replicant to suffer, to give its owners that whole master-slave energy, it has to have emotions. .... When Bryant was telling you about the Nexus-6 models, he was conning you and he knew it. The replicant's emotions aren't a design flaw. The Tyrell Corporation put them there. Because that's what our customers wanted.'

The exploitation which is ubiquitous in Jeter's world is not undertaken solely for the purpose of profit. On the contrary, money is acquired because it allows you to cause suffering with impunity (the ultra-rich are permitted to 'pre-register' the killing of homeless people, for example). Shaviro is right that the punishment for intellectual property violation in Noir combines 'the implacable severity of the categorical imperative' with 'the shattering intensity of the sublime' but Jeter's is an unremittingly vicious universe in which the presupposition that Kant's ethical system is based upon - the possibility of acting disinterestedly - is ruled out. The one moment of apparent friendship in the novel (McNihil's gift of the brain and spine of the downloader to the author whose copyrights he has violated), macabre enough in the first place, is quickly revealed to be a moment of weakness which allows him to be set up. Betrayal, as the author tells McNihil, is the essence of noir. (McNihil has optical surgery which converts the outside world into the stark monochrome world of the Noir films of the 1940s. His motivation is a puzzle throughout the novel: is it to escape modernity into a more rarefied, more beautiful world, or a a consant reminder of the world's total venality that is intended to keep him focused on the impossibility of redemption?)

But what of Jeter's own politics? A comparison of intellectual property with cattle running free in the days of the Old West is telling. Jeter is a conservative in the original American sense, committed to preserving his own liberty against the incursions of the State (which has all but collapsed in the world of Noir), big corporations and data pirates (the modern equivalent of cattle rustlers). The parallels of cyberpunk with noir are long established, but the connections with the mythology of the Old West are also instructive. Jeter's 'freelancers', like Gibson's 'data cowboys', are rugged individuals struggling on a New Frontier, this time technological rather than geographic. Although they are superficially similar, McNihil is the very opposite of Gibson's Case. Case makes his money by stealing intellectual property, McNihil by protecting it. Jeter may be hostile to multinational corporations - the real villain of the piece is the Sadean DynaZauber executive, Harrisch - but Jeter remains a purveyor of Capitalist Realism. His is a nostalgia for an earlier, almost primitive, form of capitalism. In a world in which collectivity is unthinkable, all that is left is the burnt-out case of libertarian 'autonomy'.