September 27, 2005

Jessica Rylan Interview: Sometimes I do feel this psychic connection with machines…

[the following post is by Infinite Thought]

'Look into that world of automatons, that robot-world which still invokes the name and even the mercy of God in order to get itself going, and invokes the existence of the living so as to imitate that existence more perfectly than in nature.' – Luce Irigaray, 'The "Mechanics" of Fluids', This Sex Which Is Not One

'Machinery does not lose its use value as soon as it ceases to be capital….It does not at all follow that subsumption under the social relation of capital is the most appropriate and ultimate social relation of production for the application of machinery' – Marx, Grundrisse

The future masters of technology will have to be light-hearted and intelligent. The machine easily masters the grim and the dumb – Marshall McLuhan

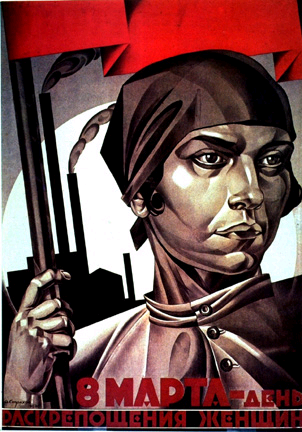

There's a scene in Dziga Vertov's 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera which combines footage of women doing a variety of different activities: sewing, cutting film (with Elizaveta Svilova, Vertov's wife and the film’s actual editor), counting on an abacus, joyfully making boxes, plugging connections into a telephone switchboard, packing cigarettes, typing, playing the piano, answering the phone, tapping out code, ringing a bell, applying lipstick. The cut-up footage speeds up to such a frenzy that at one point it becomes impossible to tell which activity is done for pleasure, and which for work. This is a vision, long before desktops, mobiles, call-centres and the invention of temp agencies, of the optimistic compatibility, perhaps even straightforward identification, of women with the boundless manifestations of technology and artifice….In February 1966, a group of Belgian women working in arms manufacture demand equal pay for equal work. Calling themselves "women machines", they go on strike, disrupting work for twelve weeks, behaving in the same way, they argued, 'as one carries out a war'...

Women have always been desired by the machine. It has needed them for their deftness, their smaller hands, their capacity to work quickly and, initially at least, to demand less for doing so. Rarely, of course, have women ever been on the side of construction (though Waterloo Bridge, the longest bridge in London, rebuilt by women during World War II, magnificently undermines the idea that women’s work is 'small-scale'). For women, typically, the machine dreams through them, as Sartre famously noted, inculcating just the right level of distraction for maximising performance - the erotic dreams a curious byproduct. The proliferation of typewriters and telephones in 1870s and 1880s, and the concomitant mechanisation of information, allowed women to compete for jobs they could easily do better than men. In other words, 'a large number of higher-salaried men with pens who added columns of four-digit numbers rapidly in their heads were replaced by lower-salaried office workers, many of them women, with machines' (Lisa Fine, The Souls of the Skyscraper).

Capital was and is increasingly feminised via its machines; high-rise gyno-capitalism literally making nothing, better, faster, as the circuits babble ceaselessly among themselves. A million data-entry workers sigh as the tips of fingernails clatter interminably; call centres trilling with the trained tones of treble-tone perfection; fembot recordings at stations instructing harried commuters where to be and when; on the other side of the divide, stitching, sewing, the sharing of space made easier by the capacity of women to almost vanish, despite their tendency to curve and accessorise. Far from possessing a deep-seated aversion to the unnatural, the contrived, the processed, women have forever shown their speedy capacity to adapt to and out-automate the machine, even as it uses and abuses them in turn.

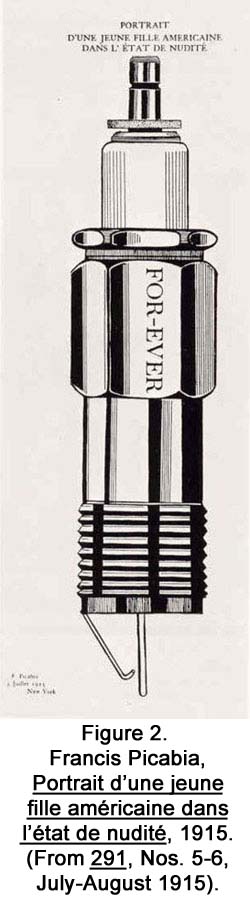

In one sense, we have always known this: that most machinic of data, communication, has always been the preserve of women, for better or worse (Kant’s Anthropology peevishly banishes 'the girls' to the other room for frivolous chatter, while the men discuss the important issues of the day). When silver screen superstar Hedy Lamarr co-invented a secret communication system in order to help the allies defeat the Germans in World War II, MGM kept this aspect of her life under wraps as incompatible with her 'star' image (even though she had already done her best to deflate the illusion, even at the very beginning of film idolatry - 'any girl can be glamorous. All she has to do is stand still and look stupid'). From mangles to washing machines, dictation to cryptography, espionage and war-time code-breaking, the manipulation and mechanisation of the feedback of machine, information and transmission has needed women often a lot more than it has needed men. As Gary Sauer-Thompson asks in a discussion of Picabia's Portrait d'une jeune fille americaine dans l'etat de nudite: 'If women…have become machines - in terms of the male gaze - then what has happened to men?'

What happens now, however, if we go beyond this? When communication becomes not something to understand and uncover but is the production of pure noise? When the machine, instead of dreaming through women, is created, maintained and exploited by them?

(from)

(from)

Jessica Rylan is the future of noise, in the way that men are the past of machines. Tall, slender, politely dressed, bespectacled…across a crowded clerks' office, Kafka's heart starts to pound. While the sirens of unpleasantness continue to seduce the male noise imaginary, Ms Rylan and her home-made synth-machines pose a delectable alternative: what if, instead of abject surrender to the hydraulic-pain of metal-tech, we forced the machine to speak… eloquently. But let's not be coy: there’s nothing nice about her noise – no concessions to the cute, the lo-fi, the cuddly or the pretty.

How does Rylan herself describe what she does? How does it fit with the rest of the Noise 'scene'? She has written on her website about the idea of 'personal noise', so I ask her to expand on this a little: 'So many people doing harsh noise, trying to live up to this Merzbow image. It seems really impersonal to me a lot of the time… Some people that do noise play really harsh. You’ll see them playing they’re like gritting their teeth, and playing this noise and it’s like, you don’t even enjoy your music. What are you doing? To me, it’s one thing if you’re doing art music, it’s totally abstracted and you don’t think about the emotional part, but when someone’s doing this loud music and it’s harsh, it should be about something.'

About something. There’s something perfectly poised about Rylan's fusing of form and content. She confesses her fondness for the organic all around her: 'I'm really interested in plants. That synth I’ve been playing, that personal synth is not very much like a plant but I have this other one I’ve built that I might start touring with, the natural synthesiser, and that one is more like a plant, more wavery sounds, and swishes, and there are time-frames that you kind of hear in the world, burbling water, whatever'. Replicating the organic via the inorganic, correcting the hippie idea that the best way to commune with nature is to be as close to it as possible (the familiar horror of beards, body odour, weed, letting it all 'hang out', the inelegance of the 'natural, comfortable' mob). On the contrary, the only way to even approach the artificiality of the natural is to outstrip and outdo its simulation, which Rylan does by plugging and unplugging her voice and body into the auto-circuits of an oneiric eroticism that weaves beguilingly amidst a series of disconcerting incongruities: 'Although it is characteristic of noise to recall us brutally to real life, the art of noise must not limit itself to imitative reproduction' (Luigi Russolo).

There’s no interest in nature in the noise scene, she says. 'This whole world, we’ve all gone indoors, we look on the internet, watch Tv, read books, watch movies, take drugs whatever. It’s all very interior, we don’t spend any time in the world. I mean, I did that for years, but there's all this stuff in the world that is so cool, that I feel like I didn’t pay attention to. It was really neat, we went to the museum today and there was this one Van Gogh painting, and looking at it, the whole thing just vibrated. And I was just got really choked up, it seemed like the painting was animated. It was moving and waving like grass would wave in the wind. That kind of thing to me is really interesting, like when sounds are animated in this really detailed way. I'm still working on that. That’s more like stuff to listen to at home. But live, it's different. You want to put on a show'.

(from)

(from)

Ah, the show. Live, Rylan performs a combination of discomforting personal exposure (in the form of a capella songs played with unstinting directness towards the audience) and machinic communing with self-made analogue synthesisers feeding back to eternity fusing with ethereal, unholy vocals that haunt like cut-up fairy tales told by a sadistic aunt. I must admit the first time I saw the unaccompanied work I was taken aback, slightly appalled, even. Is that…noise? It’s just a girl reading poetry! But, in retrospect, without the disconcerting effect it produces, the rest of the show would perhaps lack a certain dimension, a certain creepy completeness. She says the British audiences respond very differently to this part of the show – at the gig the previous night, when she suggested she might do something 'quieter', the desire for 'more noise, more pain!' was shouted from the floor.

There's something deeply unusual about the way the analogue gets processed by the synths. Usually prized for its warmth, its authenticity, its richness, Rylan turns this fetishism of the vintage machine in to anti-warmth, the anti-real, a series of self-styled machines that cut up and disconnect time from itself in the present. Using analogue to out-mimic the effects of digital: 'I guess you think of warm drone when you say "analogue". The thing that is cool to me is that the analogue circuit is doing it in real time. The same thing as a tree branch shaking or something as the circuit electrically is vibrating and then that is going directly to the speaker and the speaker is vibrating, and so the circuit is vibrating in its own electrical world in the exact same way in the exact same time and to me that's really cool. If you use a computer and digital stuff that's like chopping it up and computing it, I just feel that computers operate in a time that we don't have access to. Because the instant for a computer is like four billion times a second, four million times a second. One ten-millionth of a second. What does that mean to us? I mean, we’re so slow in all our ways.' Rylan has commented before on her desire not to use any effects that mess with time (reverb, delay), but instead the machine messes with her and with itself, so you can no longer tell where the sound is coming from. In a way it no longer matters. What you see and hear is a series of deftly manipulated switches, wires and sockets attached to their creator, who circles the mechanical morass and herself emits sounds that feed back, away from and into the machine. The relation to the audience is deliberately ambiguous and highly structured – rather than the crowd-baiting outright aggression (however ironic) of most power electronics.

(from)

(from)

She confesses to a past infatuation with the work of Paul Virilio: 'I was reading all his books at that time and I was trying to do as much as I could as fast as I could, I was into changing everything as fast as I could. But he doesn’t even have an answer-machine, or a computer. Yet there’s this interview where he says how much he loves technology, I can totally relate to that. I really like that about him.' Her shows, while on the brief side now used to be even shorter, seven minutes or so, anti-indulgence personified. 'I did everything at once', she says. In many ways, this has always been the temptation of noise, to embrace the speed and brutality of the car, the machine, the 'love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness' of Marinetti's 1909 Futurist Manifesto, to live up to Russolo's demand to combine 'infinite variety of noises' using a thousand different machines (1913's Art of Noises). Whether or not the Futurists were openly or implicitly phallocratic (particularly compared to the prominence of women in the contemporaneous Soviet Suprematist movement) is perhaps secondary to the question of whether we should understand noise as the frenzied attempt to 'keep up' with machines, or with nature's most extreme sonic constructions: 'the rumble of thunder, the whistle of the wind, the roar of a waterfall, the gurgling of a brook, the rustling of leaves, the clatter of a trotting horse as it draws into the distance, the lurching jolts of a cart on pavings, and of the generous, solemn, white breathing of a nocturnal city; of all the noises made by wild and domestic animals, and of all those that can be made by the mouth of man without resorting to speaking or singing' (Russolo, 1913).

Rylan herself has had a Futurist-like transition from classicism to noise (Russolo again: 'We Futurists have deeply loved and enjoyed the harmonies of the great masters. For many years Beethoven and Wagner shook our nerves and hearts. Now we are satiated and we find far more enjoyment in the combination of the noises of trams, backfiring motors, carriages and bawling crowds than in rehearsing, for example, the "Eroica" or the "Pastoral"'). Her musical background is rather upright: 'I was in a classical children's choir, performing Mendelssohn, Bach at all these churches. It was wonderful. But then I had to go and destroy my voice by smoking all these cigarettes and screaming.' A little later, and not altogether surprisingly, she confesses her admiration for Jennifer Herrema (Royal Trux/RTX): 'she's like an albino or something, wearing a fur coat in the middle of summer. I think she’s so amazing. So trashy, but so cool'. I tell her the show put me in mind of Diamanda Galas, even though there are no obvious similarities in terms of voice or pitch. She seems pleased: 'I've never gotten that comparison, but I do really like her a lot!' There are certainly hints of a certain violent rock 'n' roll extremism to Rylan's shows which it seems has been tempered in the past couple of years:

The falling on the floor thing. Tell me about it. 'In the video (from 2002), I was at college and I fell on top of one of my professors, who that year won this MacArthur 'Genius' grant, for $500,000. He's like this genius improvising jazz musician and I just like took a dive at him. But he was cool, he just pushed me off. That was the weirdest show. But I felt good about it.' Personally, I can't think of a better way to pass a course. But things have calmed down for Ms Rylan of late. A bit.

'This year I started closing my eyes quite a lot this year, I don't know why. I just starting turning more inside. You have to be careful though. Playing with your back to the audience, it could be a position of vulnerability, but that position could also be like "fuck you, I don't care, I don't want to look at you". I've just started to try and think more about being on stage and how does it come across. All that spastic dancing…when I was playing to my friends they knew where I was coming from, but when it started being people I didn’t personally know coming to a show then they would just have these weird reactions to it. The worse one ever was at my house actually, at my loft…we were having this big party, there were like 200 people there, and so I was playing and some people came in but not that many. I was dancing all crazy, it was the best time I ever had at a show and I finished and I was so happy. And then nobody clapped and this one guy, who had been sitting on the floor got up and said "Thanks. That. Was. Very. Disturbing." And then everybody just walked out in single file. And I found out later on that the reason that only ten people had come into the space was because the people in the doorway just got stuck, deer in headlights style, afraid and couldn’t come in or something. And after that I was like "what am I doing?" That’s not what I want to communicate at all!'

So, how to avoid the blood draining from the faces of your unsuspecting audience? 'My relation to the audience has been changing. For a long time most of the shows we do are like really small, just thirty people or something. We usually play on the floor, with everyone right around you, it's more intimate. I really like that but I'm also really starting to think about…playing on the floor has become an ego thing…when there's more people at the show and you play on the floor they just can't see you….I don't want to play as loud as everyone else, but I think they turned it up louder last night. Working with feedback is tricky because sometimes it'll just get too loud and messed up. I’ve been moving on to the stage and off the floor. I had been playing on the floor for a long time. It’s like this punk rock idea like "we don’t want to have a separation between the audience and the musicians" and that’s awesome, but it's like, they paid money to see you play music! You want to put on a good show, people want to see. And it just especially sucks for shorter girls.'

Ah, Jessica! You stand on stage so girls like me can see you. It's impossible not to fall for that, but in many ways it exemplifies the careful thought involved in every aspect of her work: music, the show, the performance, the equipment. No slap-dash, jumbled-together mix of a misplaced genius-complex and self-indulgence here – go home off-the-cuff (or, ahem, wrist)-boys….

(from)

(from)

She speaks of her desire to have silence between bands at noise gigs, rather than loud pop music (as indeed happened just before Sutcliffe Jugend with a Strokes track). Purification? Timing? I think it's more a question of structure, of locating one performance amongst the others, creating a proper production. This tallies with her recent attitude towards structure in her own work:

'I used to do more improv things that were just kind of like a mess and just like whatever was, happened. But then I started writing songs and at a certain point I was like, how do I write songs with noise? So I tried to do that, which was tricky. A lot of the harsh noise bands, none of them have songs, it’s all improv, and with power electronics, they’ll have lyrics and the sounds they're going to use on certain parts but also like an open structure. That to me is the most attractive, because it’s a recognisable song, but you can also improvise. I like the idea of being very focused. I want it to be enough of a song that you could get into it, but also enough unpredictability that you really have to focus on it.'

Certainly, unpredictable effects seem to follow Rylan around - 'The first song I played last night when I went on tour in the US in February I played fourteen times in a row which somehow worked really well, and it doesn't work any more. Which is really weird because it was actually a love spell. It's called "casting a spell", and I was trying to get someone to fall in love with me. I thought if I keep doing it it'll work. But it didn't work on the person I wanted it to work on and I'm glad it didn't, in fact, I realise it would have been bad news if this person had fallen in love with me and then it seemed like it worked on some other people that I didn't want it to work on. But now my heart isn't really in that song, and it's really strange but the last few times I played it in the US, it was a total disaster. My mind and the synthesiser don't get along on this one. Sometimes I do feel this psychic connection with machines'.

You insist that there is something a machine cannot do. If you tell me precisely what it is a machine cannot do, then I can always make a machine which will do just that - John von Neumann

Where now? After a summer of extensive touring, Rylan could probably do with some time to reflect. 'Who knows what the future will be. But to be honest, I want to move out of the noise scene, although I really like it. I enjoy going to noise shows, I enjoy harsh noise but harsh noise is very self-limiting because it's only certain people that want to listen to that all the time, especially at those super loud volumes. There are certain things I wish I had more control over in what I'm doing. I did that same song in Leeds and it was just amazing, it was like this dream come true, but then the other two times I did it on this tour it was ok, but not quite at that level so you know it’s like, what I'm trying to figure out is how to recreate the experience. But not get bored. Personally I've really been trying to thing of it more as pop music, or to try and approach it like that.'

Pop-noise! If there were ever someone capable of leading such a movement, she's sitting opposite me sipping white wine in Soho while rubbish-collecting machines purr outside. But tell me more, who do you rate?

'I really like Kites and Prurient. With Kites – we have this real back and forth. We both build some of our stuff, analogue things. I really like his stuff a lot. But right now, this is terrible to say, Joanna Newsom. Everybody hates Joanna Newsom but folk, harps, high weird voice. I'm really into new folk. In the States, there's definitely a connection between the noise scene and that, or some parts of the noise scene and that kind of folk.'

Folk-noise! We talk a little bit about neo-folk and the quite, er, intriguing way this has emerged and mutated in Europe. It doesn't quite share the same complex ideological overtones in the US, apparently: 'In the US it’s kinda hippie, which I'm not as much into. But I like more traditional folk music. Because I feel that noise is a form of folk music. It's very grassroots. The thing about noise shows is a lot of the time that half the people in the audience also play. Which in a way is awesome and in another way is frustrating. We need more fans! I love that grassroots things, but there are things I think could also go to a broader audience. I hope it happens, because I think people could relate to it. It's amazing, like Merzbow, is kind of like a household name, almost. For any self-respecting hipster, they have one record or something. Even Wolf Eyes, who would've had thought that they would be as popular as they are now five years ago?’

We discuss the difference between the US, Japan and Britain with regard to noise. She speaks a little about Providence, the No Fun festival and Load Records: 'The whole Providence scene, it was a really noisy situation, and it's just grown. It was a lot of places like the Foundry, but worse. Concrete rooms, like super-reverberant, bad PAs, just gross. That's fun but...then, what is Noise? Is it like catharsis, something you have to go through, you have to face bad things in your life that you don't want to deal with and this is the way you deal with it? I don't even know anymore. I'm so used to listening to noise that it just doesn’t seem that extreme to me.' Nor, it turns out, does extreme pop music: 'Honestly, when I'm at home I listen to easy-listening music. Claudine Longet, in particular. She went crazy and killed her boyfriend, she was awesome. I'm really into melodies.'

from)

from)

So, folk-pop-noise project in mind, what else could the scene do with changing? 'The noise scene traditionally has been very interested in limited editions, fancy packaging, super fetish of the object. Which is interesting. I do think if you’re putting out a recording it’s really important to focus on it, think about the art and so on, maybe have a booklet come with it. But then you wonder, who is going to listen to all these records? That's the thing in the US now, everyone is putting out CD-R after CD-R all the time. You go to a show and you come home with like 6 or ten CD-Rs. When I was on tour with John Wiese, that was the worst. People just gave him stuff everywhere. Wherever he went, however much merchandise he sold, he left with three times as much. He was mailing stuff home all the time. But he only listens to 7 inches! Like that Merzbox…who has time to listen to that? People make all these limited releases just to trade them for other limited releases. I feel like there's a real pressure to release lot of stuff in the noise scene. It's like free jazz, improv music, putting stuff out all the time. I want to do less!'

Doing less might prove difficult. Rylan has recently received a Penny McCall grant for her work: 'I totally couldn't believe it. I had quit my job just before that, and then three days later I got the grant. This year I keep going on tour. I don't really have time to get a job! But I got to start doing something, some temp work or I've got to start selling some more synthesisers. I've sold four instruments this year. If I could just do one a month then I'll be ok'. She has also just received a post at MIT: 'I'm going to be a research associate at the centre for advanced visual studies. I’m going to get undergraduate interns to help me. I'm totally psyched.'

We discuss the potential risks of pursuing an academic career. 'When people get academic backing, that can become more important than their work. My dream is to be recognised in the academy and do more pop music, but I do feel very suspicious of academic music. It has two major traps it falls into. Either it has principles above response, like serialist composition, which nobody really likes. There's no point in making a record that no one wants to listen to, but then on the hand, all that polite applauding, yet total lack of rigour.'

'It's nice if you can rely on your equipment,' she says, before we stop to go and find some cigarettes. 'I know how to deal with my own equipment'. She's not wrong.