August 29, 2005

Noise and sonic anamorphosis

Yes, I have to concur entirely with I.T. about the drabness of last night's Noise non-event at the Red Rose in Finsbury Park. Sutcliffe Jugend were like a pantomime without the make-up, Tomkins barking such inanities as 'I --- question --- your --- right ---- to ----- exist!' (big deal, squire, I question my own right to exist) over a generic Noisetrack presided over by a gum-chewing bouncer-type. Some of the rabble were all too ready to be roused (and not a few of the gentlemen around the front of the stage looked like they had popped in on the way to maiming a prostitute in a layby) but, really, this was tepid fare, disengaging and underwhelming. It was more Oi than Noise, a rather flat rifling through the soiled underwear of yesterday's transgressions. What SJ showed, in fact, is how powerful Whitehouse are; how not just anyone can do it, that it's not just a matter of spitting invective over a feedback scree. It has to get under your skin, it has to disturb, not merely assault. If it doesn't, the organism merely closes up on itself, numbs out the excess stimuli, and the result is ennui. So it was with most of the rest of the bill, who turned out the Noise equivalents of twelve-bar blues: howling feedback (check), total lack of rhythm (check). It's tedious to say that generic Noise is as genre-bound as boyband chartpop - almost as tedious as it is to listen to this stuff. But that doesn't stop it being true. The chief argument for Noise would be that it opens up sonic channels that 'music' closes down or off, but that case is immediately invalidated if the same few sounds are trotted out ad infinitum. This kind of Noise, like a great deal of Sonic Art, doesn't break out of the tyranny of music because it remains in a negative relation to it - it defines itself by assiduously purging any so-called 'musical' elements. The austerity is admirable but the effect of this hair-shirted self-punishment is too often not the revelation of a new affective range, but a dutiful boredom.

Part of the reason that Jessica Rylan's short set towered above everything else is that she isn't afraid to include 'musical' elements in her Noise constructions; untreated, as she performed them on Tuesday's 'warm-up' event at the Foundry, her songs sounded cutesy-kooky, like a primary school Mary Margaret O'Hara. But fed through her self-constructed effects boxes and synthesizers the songs are transformed into eerie plaints, desiring machine stammers, ghost chatter, geek ectoplasm. The machines sublimate the raw material of the songs, the two together producing something that isn't present in either on their own. One song sounded like Suicide channeling the voice of a murdered child; another like 'I Feel Love' re-recorded for Eraserhead. There's something not a million miles away from Ariel Pink in the way that Rylan conjures the beguiling illusion of a sonic object that would be perfect if only you could hear it more clearly. Yet the 'perfection' is an effect (a special effect, you might say) of the blurring and distorting techniques themselves, like a kind of sonic anamorphosis. Rylan's methodology is ample proof that DIY need not mean lo-fi lack of ambition. Her noise pieces are one response to the sublimity-destroying effect of digital culture's excessive (and oppressive) high resolution clarity. Listening to the tracks on her CD, New Secret, is unsettling in the way that Sutcliffe Jugend never could be - there's a disturbing intimacy in these faux-naif recordings, the suggestion of an abused child singing nursery rhymes in the dark, or a poltergeist-exorcism broadcast on a clapped-out radio... feints and implications.... doodles and shadows ....

So, anyway, Infinite Thought spoke to Jessica today, look out for the interview soon...

_________________________________________________________________

Martin of Beyond the Implode RIP gives his view (this before he threatened to tried to precipitate his own apocalypse by singing Spurs songs deep in the heart of Arsenal territory, at least as risky an enterprise as wearing a swastika on Seven Sisters Road....)

August 28, 2005

Spincerity

Brilliant post by Tim at the Wrong Side of Capitalism, which manages to precisely identify the parallels between Blair and U2. It was prompted by this embarrassing post, which manages to combine a pro-catholic conspiracy theory about the music press (in support of the plainly dotty thesis that there was a time that the World's Biggest Rock Band belonged to the ranks of the oppressed) with the worst use of Badiou and Zizek I've yet seen. (I missed the step between U2's Irishness = Good and Nationalism = Bad, but perhaps the argument was too subtle for me). More seriously, though, Tim makes valuable points about the media's ideological complicity in Blairism.

Blair's achievement has been to shift the focus from policy and politics to personal integrity; not only to shift the focus, actually, but to eliminate the difference. What is missed in all the attacks on spin is that the fixation on spin is itself spin. And the supposed opposite of spin, 'sincerity', not only belongs to spin but is what spin requires in order to operate. That is because a 'genuine' subjective concern about, say, world hunger becomes spin the moment it is converted into a 'political' statement. Spincerity...

The question the media will typically pose is not now 'is such and such a policy wrong or ill-conceived?' but 'did X lie about it?' This contributes to a climate in which there is no expectation that a politician will resign because a policy has failed. Thus, it is more than ever important to remind ourselves that it doesn't much matter if the other Blair, Ian, lied in the wake of the assassination of Jean Charles de Menezes. The real issues, occluded behind all the intrigue about when Ian Blair got to know particular facts and the veracity of certain statements he made, are Kratos itself and the management of the Met, structural and systemic matters which Ian Blair's personal integrity has little or no bearing upon. With a twirl of his cheap conjuror ham-actor's hanky, Tony Blair has spirited away any notion of 'objective responsibility' - what counts, we are supposed to think, is what he feels. And since Tony will always believe he is right, then he must be, OK?

August 26, 2005

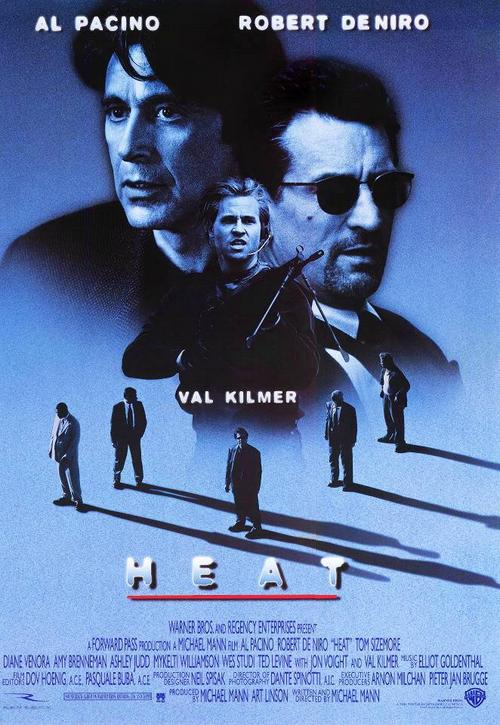

Don't let yourself get attached to anything: post-Fordist crime in Michael Mann's Heat

Re-watching Michael Mann's Heat, now a decade old.

Heat now looks not just like a great 90s film, but a great film about the 90s. There were probably none better.

This is a post-Fordist organized crime movie, in which the scores are undertaken by crews, not Families, in an LA of polished chrome and interchangable designer kitchens, of featureless freeways and late-night diners, a no-place that is very far from being a utopia. All the local colour, the cuisine aromas, the cultural idiolects which the obvious comparison pieces, the Coppola and Scorsese gangster flicks of the seventies*, depended upon, have been leeched out, painted over, re-fitted and re-modelled. You could be anywhere ... It is a world without landmarks. Ours: a branded Sprawl, where markable territory has been replaced by endlessly repeating vistas of replicating franchises. The ghosts of Old Europe that stalked Scorsese and Coppola's streets have been exorcised, buried with the ancient beefs, bad blood and burning vendettas somewhere beneath the multinational coffee shops.

You can learn a great deal about the world the film projects from considering the name of the character De Niro plays - 'Neil McCauley'. It is an anonymous name, a fake passport name, a name that carries no culture freight, that is bereft of history, as unrevealing as a forced smile (compare 'Corleone', and remember that the Godfather was named after a village). McCauley is perhaps the part that De Niro played that is closest to the actor's own personality: a screen, a cipher, depthless, icily professional, lacking in reflexivity, stripped down to pure Method ('I do what I do best'). When McCauley meets the love interest, Eadey, he is reading a book on metals.

McCauley is no mafia Boss, no puffed-up chief perched atop a baroque hierarchy governed by codes as solemn and mysterious as those of the Catholic Church and written in the blood of a thousand feuds. Ask his Crew if they are blood brothers, and they would laugh at you. They are professionals, hands-on entrepreneur-speculators, crime-technicians, whose credo is the exact opposite of Cosa Nostra family loyalty. Family ties are unsustainable in these conditions, as McCauley tells the Pacino character, the driven detective, Vincent Hanna. 'Now, if you're on me and you gotta move when I move, how do you expect to keep a... a marriage?' Hanna is McCauley's shadow, forced to assume his insubstiantility, his perpetual mobility. Like any group of shareholders, McCauley's crew is held together by the prospect of future revenue; any other bonds are optional extras, almost certainly dangerous. Their arrangement is temporary, pragmatic and lateral - they know that they are interchangable machine parts, that there are no guarantees, that nothing lasts. Compared to this, the goodfellas seem like sedentary sentimentalists, trapped animals rooted in dying communities, doomed territories. McCauley and his Crew couldn't be less interested in Territory; it is Capital they are after. As McCauley tells those in the bank during the heist, 'We're here for the bank's money, not your money.'

McCauley's creed - he says it twice - could be written in every post-Fordist boardroom. 'A guy told me one time, "Don't let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner."' McCauley's problem, of course, is that, when it comes to the crunch he is unable to live by this. His fate could stand as a warning to all of us, workers and managers, that late capitalism and attachment do not mix.

* Goodfellas came out in 1990, but it was already elegiac, already about a moment that had passed. Casino was actually released in the same year as Heat, and it, too, was self-consciously a period piece, a historical drama about the near-past.

August 21, 2005

your craft is not to blame for what must be inflicted now

Why is the Met's disastrous shoot-to-kill policy called Operation Kratos?

Look no further than the comments box for this post on Lenin's Tomb, where Savonarola finds the answer in Aeschylus. The following passage from Prometheus Bound does indeed provides an insight into 'the mythological unconscious of the State'.

A rocky mountain-top, within sight of the sea. Enter Kratos and Bia, dragging in Prometheos. Hephaistos follows.

Kratos: Here we have reached the remotest region of the earth, the haunt of Skythians, a wilderness without footprint. Hephaistos, do your duty. Remember what command the Father laid on you. Here is Prometheos, the rebel: nail him to the rock; secure him on this towering summit fast in the unyielding grip of adamantine chains. It was your treasure that he stole, the flowery splendour of all-fashioning fire, and gave to men - an offence intolerable to the gods, for which he now must suffer, till he be taught to accept the sovereignty of Zeus and cease acting as champion of the human race.

Hephaistos: For you two, Kratos and Bia, the command of Zeus is now performed. You are released. But how can I find heart to lay hands on a god of my own race and cruelly clamp him to this bitter, bleak ravine? …

Kratos: What is the use of wasting time in pity? Why do you not hate a god who is an enemy to all the gods who gave away to humankind your privilege?

Hephaistos: The ties of birth and comradeship are strangely strong.

Kratos: True, yet how is it possible to disobey the Father’s word? Is not that something you dread more?

Hephaistos: You have been always cruel, full of aggressiveness.

Kratos: It does no good to break your heart for him. Come now, you cannot help him: waste no time in worrying.

Hephaistos: I hate my craft, I hate the skill of my own hands.

Kratos: Why do you hate it? Take the simple view: your craft is not to blame for what must be inflicted now.

Hephaistos: True - yet I wish some other had been given my skill.

Kratos: All tasks are burdensome - except to rule the gods, no one is free but Zeus.

Hephaistos: I know. All this (indicating Prometheus) is proof beyond dispute.

Kratos: Be quick then; put the fetters on him before the Father sees you idling.

Hephaistos: Here, then, look! The iron wrist bands are ready (he begins to fix them).

Kratos: Take them; manacle him; hammer with all your force, rivet him to the rock.

Hephaistos: All right, I’m doing it! There, that iron will not come loose.

Kratos: Drive it in further; clamp him fast, leave nothing slack.

Hephaistos: This arm is firm; at least he’ll find no way out there.

Kratos: Now nail his other arm securely. Let him learn that all his wisdom is but folly before Zeus.

Hephaistos: There! None - but he - could fairly find fault with my work.

Kratos: Now drive straight through his chest with all the force you have the unrelenting fang of the adamantine wedge.

Gravatar Hephaistos: Alas! I weep, Prometheos, for your sufferings.

Kratos: Still shrinking? Weeping for the enemy of Zeus? Take care; or you may need your pity for yourself.

(Hephaistos drives in the wedge)

Meanwhile, Michael Portillo shames the pitiful efforts of the so-called liberal left by proving that being a columnist on a British broadsheet does not necessarily require brain death, with a typically cogent assault on the 'mess at the Met':

'For days after the killing it was reported that de Menezes was running, and that he had vaulted the ticket barrier into Stockwell station. Some of that misunderstanding may have arisen innocently, if for example a witness saw a man leaping the barrier without realising that he was in fact a police officer in plain clothes. But the police did not correct that misinformation. The public was invited to believe that if a man is running it is reasonable to deduce that he has a guilty reason for doing so.

To add to that impression the Home Office leaked the story that there were irregularities in de Menezes’s immigration status. That is disgraceful. Even if it were true it would be irrelevant to his death, but this poison was released, I suppose, in order to help explain why the man was running away (which, as it turns out, he was not). The Home Office’s conduct has to be investigated too, which is another reason for needing a public inquiry.

... The commissioner has repeatedly referred to the Met’s shoot-to-kill policy. That has puzzled me. When I was defence secretary, ministers used to spend hours agreeing the rules of engagement for our troops deployed in, say, Bosnia. Quite rightly, elected politicians signed off the detailed conditions in which British soldiers could use lethal force. It should not be a matter for a policeman to decide in what circumstances a person can be killed in Britain. Elected people should have that responsibility.

... It is not clear what Blair hoped to achieve by declaring his shoot-to-kill policy. It seems unlikely that he could intimidate terrorists who were intent on committing suicide anyway. What I fear is that the policy created a mood of over-excitement among armed officers when cool heads were needed. Blair’s recent comment that de Menezes’s death must be seen in the context of the 52 deaths of victims of terrorism is unintelligible and demonstrates another failure of judgment.

.... Ministers were keen enough to set up public inquiries when they thought that private train companies might have caused passenger deaths through negligence. The case for an inquiry in the de Menezes case is irresistible. If the government is lucky in its choice of judge, it might just produce another whitewash.'

August 18, 2005

european grey

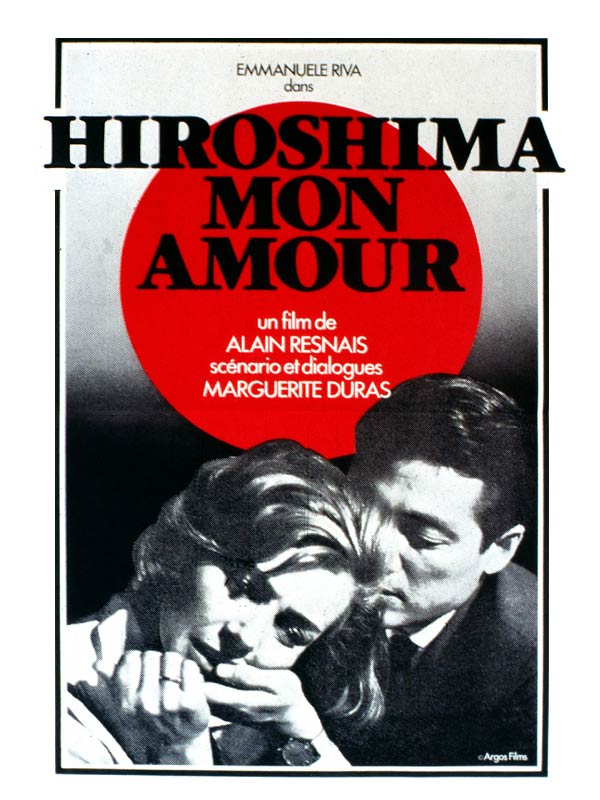

Owen on Grey Europa... must also mention Warsawza from Bowie's Low, after which the proto Joy Division Warsaw were named ... and as for greyness there is of course 'Fade to Grey' (Visage being total europhiles, which is what made them so fascinating to the US) but interesting that the phrase 'European grey' occurs in the song 'Hiroshima Mon Amour', named after Resnais/Duras' film ... a New Wave (in the cinematic sense) take on Japan and China seems to be as central to that moment of British synthpop as does a pure Europhilia...

August 17, 2005

zombie politics

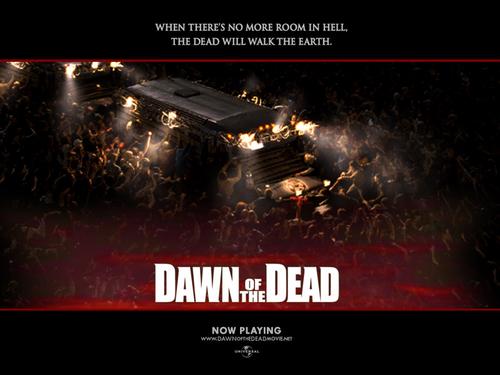

An uncanny and disturbing convergence last night when, after watching the (surprisingly effective) non-Romero Dawn of the Dead remake, I caught up with the ITV news revelations on the de Menezes shooting, as detailed with typical thoroughness on Lenin's Tomb here and here.

Watching Dawn of the Dead, which keeps faith with zombie movie lore that a zombie nust be shot in the head, one could hardly fail to be reminded of Sir John Stevens' now notorious statement that 'there is only one sure way to stop a suicide bomber determined to fulfill his mission: destroy his brain instantly, utterly.'

In their 'Alien-Nation: Zombies, Immigrants and Millennial Capitalism', ethnographers Jean and John Comoroff describe the way in which the zombie has re-emerged in the vernacular political unconscious of global capitalism. They show that the figure of the zombie and the zombie-maker plug the gaps in narrative produced by newly precarious global conditions. The 'preternatural production of wealth, ... its fitful flow and occult accumulation' and 'the destruction of the labour market by technicians of the arcane' call for a narrative of witchy manipulation, annulment of automony and redemption. (The Comoroffs' 'millenial capitalism' promises damnation and salvation in equal parts.) The zombie becomes associated in particular with that figure steeped in suspicion and exotic dread, the immigrant.

Which return us to de Menezes. One of the most disturbing aspects of the affair is the (apparently) spontaneously-occurring popular fictionalization of the events. De Menezes wore a bulky coat --- he vaulted the barriers ---- he ran away when chalenged by the police ---- The degree to which the authorities were responsible for propagating this wholly untrue account remains unclear (if they are primarily responsible for it, one can only wish that their intelligence before the event were even a fraction as effective as their capacity to cover up after the event.) In any case, it seems that an account was allowed to emerge (with the collusion of the Home Office and the police) which was less a straightforward conspiracy than a managed confabulation. Confabulation is defined as '[t]he unconscious filling of gaps in one's memory by fabrications that one accepts as facts'. Many cases of confabulation are prompted by trauma, by the sudden, violent puncturing of our sense-making capacity by events that exceed our attempts to narrativize them. But this breach of narrative sense is radically intolerable, and, forced to choose between senseless facts and a story that accords with our previous picture of the world, the nervous system will select for the familiar but false.

Two posts on Posthegemonic Musings track this process in relation to the recent Terror attacks in Britain. First, there is the shock itself, the suspension of narrative and of sense; then there is a post-hoc rationalization, in which facts are sacrificed for the sake of narrative coherence and psychological well-being. 'The original accounts, then, are symptomatic of a social fantasy secured by the state. They are elaborated from the original acquiesence that assumes that "por algo será," "there must be a reason," and proceeds to conjure one (or here, several) out of the confusing series of sensations produced in the event itself.' Through such 'percepticide', that 'police and public alike are subject to the state's capacity to organize our perceptions, to secure our complicity with its violence at some level far beneath consciousness.'

Since de Menezes was treated as a subhuman monstrosity, there must have a reason for such treatment. The post-hoc confabulations - de Menezes' wearing of a bulky coat, vaulting of the barrier and running when challenged - fill the gap where no actual reasons exist. The monstering of de Menezes was reinforced by the Home Office's leaking of dubious 'information', significantly, of course, concerning his immigration status. (All of which produced the grotesquely humorous spectacle of people happily accepting the thinnest of pretexts for the shooting: 'well, what did he expect, wearing a bulky coat in hot weather?' 'Well, he wasn't legal, he shouldn't have been there in the first place'.) The most absurd 'signifier of monstrosity' to yet be offered up is de Menezes' supposedly 'Mongolian eyes'. Witness also the counterfactual strategy rightly derided by Bat: : the 'Constant hysterical invocation of an absurd counterfactual scenario: "What if he actually had been a suicide bomber?"'

The new Dawn of the Dead, like Romero's original, is a powerful parable for times of immigration, transnational capital and massive 'precarity'. The objects of dread here are the displaced masses, those who belong nowhere, who have no place to which they can return, and whose one remaining affect is a voracious hunger, for as Steven Shaviro put in 'Capitalist Monsters' (Historical Materialism vol 10:4), 'in the American films [as opposed to the original South African folklore] the zombies are not workers and producers, but figures of nonproductive expenditure. They squander and destroy wealth, rather than create it.' In both Dawns, the human survivor-survivalists famously hole up in a shopping mall, protecting what is 'rightfully theirs' from the hordes of those who have no 'right' to consume but who threaten to do so without limits.

The most powerful moments in the new film, however, happens when the humans leave the mall and board a specially-reinforced motor vehicle. It echoes a similar image in Spielberg's brilliantly traumatic War of the Worlds, (itself an SF riff on Empire and colonialism), where a car - symbol of a besieged American consumer autonomy - is mobbed by the disenfranchised and the desperate. A definitive image of American dread as the great car economy crawls towards collapse....

August 16, 2005

words of wisdom

'[A]ny use of the term 'islamofascism' or its derivatives (other of course ... than to interrogate and critique that supposed category itself) immediately disbars the user from being considered a serious commentator or thinker on these issues.

Any counterexamples? Seriously. Even the more intelligent right-wingers don't use this idiot empty shibboleth. So... is there anyone who attempts to think with the category 'islamofascist', let alone who think it explains anything at all, who's worthy of intellectual respect?

China Miéville tells it like it is in the comments to this post on Lenin's Tomb.

UPDATE:

Also on this - Infinite Thought and Adam Kotsko

August 15, 2005

Why I don't want to belong to a reality-based community

Somehow I missed the whole floating of the concept of 'reality-based community' last Autumn. It emerged in a response to comments by a Bush aide, reported in October 17, 2004, New York Times Magazine article by Ron Suskind:

"The aide said that guys like me were 'in what we call the reality-based community,' which he defined as people who 'believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.' ... "That's not the way the world really works anymore," he continued. 'We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.'"

All of which, including the reference to Empire, sounds like it has come from the mouth of a Philip K Dick character (Dick famously wrote that the 'Roman Empire has not ended'.)

One of the many fascinating things about the aide's remarks is the reversal of the view that it is the role of political authority (particularly on the right) to impose a reality principle. Psychoanalytically, it is a confirmation that there are 'always two fathers': in addition to the stern patriarchal Father who forbids (the name/no nom/non of the Father) there is also the obscene 'Father who enjoys', he who has total access to enjoyment. I'm reminded of the phantasmatic delirium of

Cathy O'Brien's Trance-Formation of America: the True Life of a CIA Mind Control Slave, in which the whole of the postwar American establishment, including key members of the current administration, are presented, Day Today-like, as slavering, polymorphously perverse torture-junkies. (There's a scene, in fact, in which Dick Cheney and others are depicted participating in a hunt of human beings that is curiously reminiscent of similar events in Grant Morrison's Invisibles, where Sir Miles Delacourt, the representative of Anglo-authority, leads a pack of red-jacketed toffs in a hunt of 'undesirables.) Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut and The Shining, similarly, both play upon the idea of a controlling elite of sadists who impose one reality on us, while frolicing in a zone of radically unbound libido themselves.

Suddenly, the no-limits transgressivism of the Sixties has been appropriated by the master class. It as if the Sixties' situationist slogan has been adapted: no longer, 'be realistic, demand the impossible' but 'produce reality, impose the impossible'. And at a stroke, the postmodern orthodoxy whereby the media, as a certain poorly-rehashed version of Baudrillard would have it, are the producer of an illusory realm of representation, is overturned. Now, it seems, it is the media who remain in thrall to 'reality', whereas the elite are free to produce their own reality.

What is significant about the aide's declaration is not so much that he believes this to be the case (we all know that) but that he has been prepared to say it, to make esoteric white magical doctrine public property. (Which is significant, because while we know it, the big Other doesn't). But I think Adam Kotsko is right to resist identification with the 'reality-based community'. To do so is in fact to allow oneself to be subjugated to Capitalist Realism. Yes, it remains crucial that the power elite's obfuscations, dissimulations and inconsistencies be exposed. But to fight on the terrain laid down by the current Masters of Reality is already to have lost. For the Masters to concede that the current mode of 'reality' is only one possible version is to also to accept that new realities not governed by them are possible. And Adam is correct, we should put our efforts into producing those realities, not confine ourselves to reforming the current version.

UPDATE: Pas au-dela's thoughts on the 'limits of a reality-based community', from a while back.

August 10, 2005

The religion of everyday life

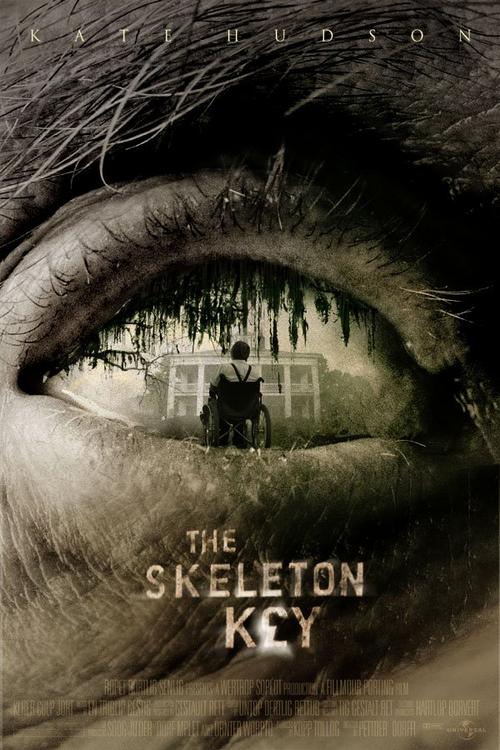

Me on The Skeleton Key over at Hyperstition.

I think the film provides an answer to the question Steven Shaviro posed a while back in an excellent post on commodity fetishism. He was addressing Zizek's take on Marx's thesis in The Sublime Object of Ideology. The genius of Zizek's take on commodity fetishism resides in his fidelity to Marx's argument; he reinvigorates a concept that had become a tired theoretical commonplace simply by reading Marx very closely.

For Zizek, the error of the standard account of commodity fetishism was to have conceived of ideology merely as a species of illusion. Strictly speaking, however, ideology is to be located in the relationship between belief and behaviour, not at the level of belief alone. The ideological stance is thus: 'I don't believe it [in other words, I have no illusions] but I do it any way.'

Steven asks:

'But why does Zizek, in this turn to material practice, still characterize what he finds there in terms of “belief,” which is to say cognition? Following Zizek’s own logic, we should say that commodity fetishism is not a matter of belief or ideology. It doesn’t belong to the category of mystification, or intellectual (mis)apprehension, at all. Rather, fetishism or animism is a set of ritual practices, stances, and attunements to the world, constituting the way we participate in capitalist existence. Commodities actually are alive: more alive, perhaps, than we ourselves are. They “appear,” or stand forth, or “shine” (the word Marx uses is scheinen) as autonomous beings. Commodities don’t just “believe” for us; much more, they usurp our day-to-day lives, and act pragmatically in our place. The “naive” consumer, who sees commodities as animate beings, endowed with magical properties, is therefore not mystified or deluded. He or she is accurately perceiving the way that capitalism works, how it endows material things with an inner life. Under the reign of commodities, we live — as William Burroughs said we did — in a “magical universe.”'

But the point is that there is no 'naive consumer' who 'believes' that commodities are animate beings. Asked if they think that commodities are alive or possess will, consumers will snort derisively. Nevertheless, they will continue to act as if commodities are animate entities.

There is, however, no question of the behaviour without the belief, no possibility of a short cut which circumvents belief altogether, because people will only perform the ritual practices if they are confident that they 'know they mean nothing'. Belief is indispensable to the ideological operation but only as something disavowed. We come, then, to a surprising conclusion: on the level of belief, far from being about the consuming of illusions, capitalist ideology is about the explicit refusal of illusions - but it is only through this refusal that illusions can be consumed at the level of behaviour.

To return, then, to The Skeleton Key. Caroline can only be duped into ritualistic involvement in Hoodoo precisely because she does not believe in it. The crucial illusion lies not in the content of her beliefs, but in the status that she accords to her belief. She thinks that what is most important is not what she does, but what she believes. She is confident that her participation is only on the basis of the belief of an Other, and therefore doesn't 'count', much in the same way that consumers, who at the level of belief are hard-headed, disenchanted Anglo-Saxon utilitarians, can participate in capitalist animism - because it is not they who believe, but the commodities themselves.

August 08, 2005

What the terrorists want

One of the most irriating post-7/7 media developments has been the way in which Terrorists have to come to function as a 'bad' big Other, whose demands we are duty-bound to flout. Ordinarily, we are compelled to obey the big Other or to maintain it in ignorance (witness the pre-7/7 situation, in which every breach of social conformity threatened to 'damage London's Olymic bid'). In the case of the bad big Other, we must do exactly the opposite of what it wants. More or less any activity - from the production of hardcore pornography to travelling on public transport - becomes compulsory if its cessation is deemed to be 'what the terrorists want'.

_________________________________________________________________

The clamour for MPs to cut short their holidays is as ill thought-out as the legislation they will produce if they continue to sit. What will they do to aid the situation? I think we know. In a spirit of kneejerk authoritarianism they will draft draconian bills that will do nothing to capture or deter any terrorists (on the contary) but which will remain on the statute books to be deployed for dubious and counter-productive purposes at some later date. The statistics from Gary Younge of The Guardian cited by Lenin in his letter from London at Direland make sobering reading: "According to Home Office statistics, 97% of those arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act - a series of draconian measures supposed to thwart the IRA - between 1974 and 1988 were released without charge. Only 1% were convicted and imprisoned … More than 700 people have been arrested under the Terrorism Act since September 11, but half have been released without charge and only 17 convicted. Only three of the convictions relate to allegations of extremism related to militant Islamic groups." Think that's only the view of moonbat middle class lefties? Well, here's The Economist, from last week: '[S]tringent measures are already in place in Britain so it is unclear how much reassurance such new laws would give the public. Worse, there is a risk that, if such laws are hastily drawn up and indiscriminately applied, they would further alienate young British Muslims. If so, they could be every bit as counterproductive as some of the measures introduced by past British governments, supposedly to prevent Irish republican terrorism, which only served as a recruiting-sergeant for the IRA.' Also check this, which concludes: "Tony Blair this week vowed that his government would yield 'not one inch' to the terrorists. It just has."

_________________________________________________________________

Language watch: note the use of the increasing prevalence of the word 'radicalization' in media discourse. It now officially means, it seems, 'turned into an unreasoning maniac'.

It would make a dog drowning in petrol laugh

I've showed admirable self-discipline in not mentioning this series of Big Brother, but anyone who has watched it should read Charlie Brooker's phorensically precise and uproariously hilarious character assasination of this year's housemates.

Speaking of great writing, if we all wish hard enough the Master might just return. (He had a thing or two to say about BB as I recall.)

londonunderlondon repeat

Scanshifts' and my 'journey through London's lost rivers', londonunderlondon, is repeated tonight on Resonance.

August 07, 2005

Another day, another dullard

Lenin rightly pours scorn on Nick Cohen's latest cup of drool. Lenin is right, of course: it's wearisome to, once again, have to correct Cohen's manifold fallacies of reasoning, grotesquely inapt analogies and factual errors. But how many times will be allowed to issue the exact same, more or less word-identical 'Islamofascist' rant? And, more broadly, why should we have to endure such a low level of intellectual discussion in British newspapers? An inability to construct coherent arguments, a propensity for ad hominem attacks and a kneejerk anti-intellectualism is not the only thing that Cohen, Liddle, Toynbee and Aronovich share. On major issues, you would be hard pushed to find any major disagreement amongst them. They, the first to trumpet the freedoms we allegedly have in Britain, are a depressingly compliant New Labour Pravda, obediently defending the party line by pushing Capitalist Realism ('well, it might not be ideal, but it's the best you can expect...')

Cohen seems genuinely unable to grasp that people may well share his professed hopes for Iraqi people, whilst completely repudiating the imperialist and militaristic means he advocates for achieving them. Thus, what is at stake is not his 'sincerity' (it's telling, isn't it, that Blairites should be so obsessed with sincerity), but the consistency of his position. Cohen's bleating about the 'middle class left' being unable to take opponents at their word, which compounds two fallacies (straw man and ad hominem) neatly exemplifies the same vice he is ostensibly decrying.

As a neo-con fellow traveller, Cohen is as happy to wash his hands of the blood of the Iraqi civilians murdered and tortured by the allies as were the apologists for Stalin in the thirties. (And - talk me through that one again, Nick - just how is the analogy between support for Stalin and being anti-war supposed to work? Even he has to grant that no-one in the anti-war coalition was a Saddam lover.)

Cohen's argument, such as it is, rests on a senseless equivocation between Saddam and Islamism. That equivocation was unsustainable before the bombing and occupation of Iraq; it is completely absurd now. As we all now know, the lie that Saddam and al Qaeda were connected brought about the very situation it purported to oppose; namely, transforming Iraq from one of the most secular states in the region to a hotbed of Islamist terrorism. If your bugbear is really 'Islamofascism', then the logical position to adopt vis-a-vis the 'war' on Iraq would have been to vigorously oppose it. Why, then, are there so few anti-Islamofascists who opposed the Iraq blitz? The answer, presumably, is that the pro-war, anti-Islamist camp make a simple minded equivalence: both Saddam and Islamofascism are evil, all evil is essentially the same and is best dealt with by use of military force, therefore...

August 04, 2005

Suicide bombs and myths

Ahead of his documentary tonight on suicide bombers, an interesting interview with former CIA agent Robert Baer by Andrew Billen in The Times on Tuesday. Choice cuts:

"We kept on asking the families the dream question: ‘Where do you see your son now?’ And none of them see them other than in Heaven. By the way, 72 virgins never came up. It’s a myth.

“The other one thing is, ‘they hate us’, which is just total bullshit.”

Is it? “Yes,” he says, “it is.”

In a school run by Hezbollah, he asked a class dominated by the daughters of “martyrs” if they watched US television. “Everybody raised their hand. And what did they watch? Oprah. I said, ‘How can you watch this crap?’ And they said, ‘No, she’s great. We love Oprah.’ So, it’s nothing to do with a hate for the West, or a cultural divide. It may have become that with bin Laden and the Sunnis, but for the Shia, it wasn’t.”

He points to Beirut, a surprisingly Western city. “It’s much more decadent than London. You can go into places in Lebanon where they still serve drugs across the bar. You’ve got all-night dancing, all-night partying. You’ve got very Western art. And it doesn’t seem to bother Hezbollah. So, it wasn’t our values. It wasn’t Western values. It’s Western presence. They want us to get out.”

... So, I say, if we want to stop being attacked, what do our governments have to do? “The first thing is get out of Iraq. To pretend this has nothing to do with Iraq is idiocy. I mean, I don’t know if it’s in the back of these people’s minds or if they think about it all day long, but what they see is that we attack Muslims, we provoke the killing of Muslims, Shia or Sunni, we provoke what they call ‘fitna ’, which is chaos among the Muslims. They see it as neo-colonialism, hate for Muslims. And the same thing with the Palestinians. They do not believe that Israel is an accident, that it was founded from a feeling of guilt after the Second World War. They think it’s an attack from the West, an outpost of Western colonialism.”

The abhorrence produced by suicide bombing is fascinating and, prima facie, puzzling: as if the annihilation of the terrorists by their own hand somehow made the atrocity worse. You would think that the objection to al-Qaeda style attacks is that they target civilians. Militarily, a willingness to die makes the enemy more difficult to fight - but ethically, surely there is little difference between a suicide bomber and a bomber concerned to preserve his own life. So it would seem. But if there are 'Western values' now, such values insist upon the sacredness of individual life; so that to willingly give life up 'strikes at the heart of western values' much more directly than does the taking of 'innocent' lives. From the POV of the self-styled guardians of the west, isn't this willingness to die - and to die for a Cause - one of the most disturbing features of what Blair calls 'these people'?

UPDATE:

Reader David Sneek writes with a quote from Thomas Friedman which perfectly illustrates my point: "The Palestinians are so blinded by their narcissistic rage that they have lost sight of the basic truth civilization is built on: the sacredness of every human life, starting with your own."

Infinite Thought with some queries and extrapolations. I think that what interests me is the discrepancy between and what is 'really' objected to, ostensibly (i.e. the killing of civilians) and the language used ('suicide bombers'). Is there more at stake here than a rhetorical equivocation of the latter with the former? (One interesting thing to come out of Baer's documentary last night was the fact that suicide bombing originated as a technique used against military adversaries.) I think that it would be interesting to think through further the relationship between capitalism's systemic suicide and its sacramentalization of individual organic life. To what extent does capitalism's massive self-destruction depend upon positing respect for individual life as its core value? How necessary is this ruse?

August 03, 2005

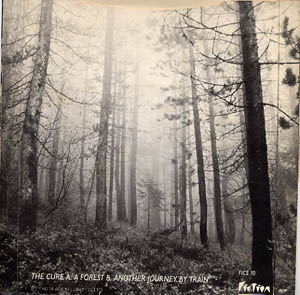

IT DOESN'T MATTER IF WE ALL DIE: THE CURE'S UNHOLY TRINITY

'Goth took hold as both a suburban and provincial cult, in which young men and women with heavily powdered faces, mourning clothes and Robert Smith's hairstyle could be seen at domestic ease in towns like Littlehampton and Ipswich.' – Michael Bracewell, England is Mine, 119-120

Any discussion of Goth will remain incomplete if it doesn't deal with The Cure.

Goth and the suburbs enjoy a peculiar intimacy (no-one knows this more than Tim Burton, whose Edward Scissorhands brilliantly laced the Avon scent of the suburbs with the perfume from Goth’s flowers of romance), and is there a group more suburban than The Cure? In England is Mine, Michael Bracewell made much of their origins in humble Crawley. ‘'Quiet and respectable, yet lacking the bourgeois superiority of nearby Haywards Heath (home of Suede), Crawley is a near perfect example of England at its least surprising,” (115) he wrote. For Bracewell, the group are the sound of the in-between spaces of English culture: the suburbs, yes, but also, adolescence, the suburbia of the soul. The Cure are the personification of the not-quite and the not-yet: not quite execrated but never really respected; not punk veterans but not yet generic Goff. The suspicion that has dogged them is that of fakery; yet inauthenticity – as existential condition – was The Cure’s stock-in-trade. You can hear it all in the grain of Robert Smith’s voice. Bracewell again: 'When Smith sang, it wasn't so much his doom-laden lyrics as the actual sound of his voice which lent the Cure their mesmeric monotony: it was the voice of nervous boredom in a small town bedroom, muffled beneath suffocating layers of ennui. Alternately peevish and petulant, breathless with anguish or spluttering with incoherent rage, Smith's voice was unique in making monotony malleable.' (117)

There is a period, a moment, when groups become what they are. Everything that has come before is preparation and rehearsal; everything that comes after is either decline or evasion. Roxy were themselves immediately – the band-brand established with the first notes of ‘Remake, Remodel’ (with the result that Ferry’s subsequent career has been a long essay in disappointment and deferred return), but it’s more usual for a group to take a while to find themselves; to emerge gradually from a cocoon of allusion, homage and plagiarism. It wasn’t quite like that with The Cure, whose best work was always produced in negotiation with their influences.

Their early mode - a spidery, punk-spiked pub sub-psychedelia – now sounds like a series of thin sketches. The Cure become themselves in that moment –lasting three albums - after they have shed the petulant quirkiness of Three Imaginary Boys but before they have entered the comfort zone of branded recognizability. By then, Smith’s panto-persona – lipstick smear, warm beer and Edward Lear – had become an archetype in the semiotic cemetery of the student disco, and the parameters of The Cure’s style were well-established – marked by what quickly became a regular oscillation between a post-Seargent Pepper jollity and a slippers-comfortable despair. All of the drama of faltering self-discovery and existential experimentalism that makes the essential triptych of Seventeen Seconds, Faith and Pornography so compelling has gone.

The Cure’s three crucial albums emerged from the shadow of two other bands, whose reputation towered above theirs: The Banshees and Joy Division. Smith made no secret of his fixation on The Banshees (with whom he would later guest as a guitarist). When the band’s first bassist, Michael Dempsey, left the band, it was because he “wanted us to be XTC part 2,” whereas Smith “wanted us to be the Banshees part 2.”

Robert Smith’s look - that clown-faced Caligari ragdoll – was a male complement to Siouxsie’s. And as with Siouxsie’s, Smith’s bird’s nest backcomb, alabaster-white face powder, kohl-like eyeliner and badly applied lipstick is easily copied; a kit to be readily assembled in any suburban bedroom. It was a mask of morbidity, a sign that its wearer preferred fixation and obsession above ‘well-rounded personhood’.

Goth morbidity arose in part from a Schopenhauerian scorn for organic life: from Goth’s perspective, death was the truth of sexuality. Sexuality was what the ceaseless cycle of birth-reproduction-death (as icily surveyed by Siouxsie on Dreamhouse’s ‘Circle Line’) needed in order to perpetuate itself. Death was simultaneously outside this circuit and what it was really about. Affirming sexuality meant affirming the world, whereas Goth set itself, in Houllebecq’s marvelous phrase, against the world and against life. By the early eighties, it was possible to posit a rock anti-tradition that had similar affiliations, an anhedonic, anti-vital rock lineage that began with The Stones – with the neurasthenic Jagger of ‘Paint it Black’ rather than the cloven-hooved demonic-Dionysus of ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ - and passed through the Stooges and the Pistols, before reaching its nadir-as-zenith in Joy Division. But Goth suspected that rock was that always and essentially a death trip. This was the gambit of The Birthday Party, who hunted rock’s mythology back to the fetid, voodoo-stalked crossroads and swamplands of the delta blues. After all, isn’t Blues the clearest possible demonstration of the discrepancy between desire and enjoyment, and therefore of the validity of the theory of the death drive? The Blues juju – or jou-jou – relies upon the enjoyment of desires that cannot be satisfied.

While the Birthday Party literalized the return to the Blues – their career a kind of hectic rewind of rock history, beginning with Pere Ubu/ Pop Group modernism and ending in a feverish re-imagining of Blues - The Cure, like the Banshees went to the other extreme. Maintaining fidelity to post-punk’s modernist imperative (novelty or nothing), they preferred a sound that was ethereal rather than earthy, artificial rather than visceral. You can hear this in Smith’s guitar, which, swathed in phasing and flange, destubtantialized and emasculated, aspires to be pure FX denuded of any rock attack. (Is this the first step towards MBV’s honeyed amorphousness?) The Cure’s version of Blues enjoyment-in-the-frustration-of-desire is auditioned in ‘A Forest’: the song in which the group find themselves, ironically, since it is a song about loss – or rather about an encounter with what can never be possessed. ‘The girl was never there’, Smith sings, a line worthy of Scritti – or Lacan. ‘Running towards nothing…. Again and again and again….’, Smith --- a suburban Scotty seeking his Madeleine --- pursues the desire-chimera, the petit objet a, through a dreamscape vividly sound-painted by oneiric synthesizers, drum-machines and Smith’s FX-saturated guitar. ‘A Forest’ was the trailer for Seventeen Seconds, and it turned out to be the album’s centerpiece. The synthesizers and the drum machine bring a moderne sheen lacking on the no-frills hustle and bustle of Three Imaginary Boys. Smith was listening to Astral Weeks, Hendrix, Nick Drake, Bowie’s Low, and wanted the album to be a synthesis of the four. The result was both more and less than this. As English as The Smiths would be, but, naturally, much more modernist and much less kitchen sink, Seventeen Seconds puts one in mind of a deserted country house, vast white spaces and empty floorboards decorated by the ornate cobwebs of Smith’s guitar. Emotionally, the effervescent petulance of the first album has drained away, but, even if the predominant mood is now moroseness, it is not yet Goth- morbid. But there is a kind of cultivated detachment, Smith assuming an ‘ostentatious absenteeism’, dissociating himself from an everyday life conceived of as a dramaturgy of effigies: ‘it’s just your part/ in the play/ for today…’

“I was 21,” Smith told Uncut in 2000, “but I felt really old. I actually felt older than I do now. I had absolutely no hope for the future. I felt life was pointless. I had no faith in anything. I just didn’t see there was much point in continuing with life. In the next two years, I genuinely felt that I wasn’t going to be alive for much longer. I tried particularly hard to make sure I wasn’t.” From its very first moments, Faith locks onto this hollow-eyed bleakness, and stays there. Affectively, the album is as improbably unwavering as Unknown Pleasures and Closer, and the Joy Division (anxiety of) influence hung over Faith like an acrid pall, the black source of its paradoxically entropic energy, what made it possible but also what would relegate it to the status of a revenant. “The whole thing was reinforced by the fact that Ian Curtis had killed himself,” Smith recalled in the Uncut interview, speaking for the post Joy Division generation (which would of course include New Order) that would deem itself inauthentic simply by dint of the fact that it had carried on living. “I knew that The Cure were considered fake in comparison, and it suddenly dawned on me that to make this album convincing I would have to kill myself. If I wanted people to accept what we were doing, I was going to have to take the ultimate step.”

Yet Faith would have benefited from pursuing its emotional mono-tone even more assiduously, if what adrenaline that remained had been drained away, and the two up-tempo tracks (‘Primary’ and ‘Doubt’) had been excised. On all the other tracks, Faith flatlines pop, bringing it as close to complete stillness as it is possible to be without coming to the grinding halt the group had sang of in an earlier, much more fleet-of-foot incarnation. There was no calmness in Faith’s stillness. It is not tranquil, but tranquilized, downer-heavy; not so much oceanic as waterlogged, swamped. (In fact, Faith was recorded on coke, not tranquillizers). The album seems to come from another planet where gravity is more powerful. The synthesizers, now foregrounded more than ever, do most to produce this effect of viscous heaviness. They have a cold warmth that fills out the sound like valium entering the bloodstream. With Faith, as with downers, it is as if the edge has been taken off. Its world is without angles, a fug, fog of bleary drear. It lacks the clinical quality of Joy Division; this is not the sound of depression, nor (as with Movement) of post-traumatic stress but of a kind of total fatalism, in which nothing much matters, where ‘all cats are grey’. Faith finds a strange exhilaration in yielding all hope, in playing dead while going through the zombie motions, ‘breathing like the drowning man’. Bracewell’s description of The Cure’s sound is nowhere more appropriate than when applied to Faith. 'There is no insight or polemic: there are no messages and no rallying anthems. Rather, the Cure are the musical expression of suburbia itself: a dense and repetitious sound, carrying a mesmeric dirge of infinitely transferable sounds, all of which sound as though they could go on for ever - like endless avenues, crescents and drives.' (115-116) Faith’s tracks are distended, hynoptic (or hypnagogic) in their repetitiousness, Smith’s mope a wraith that drifts in after introductions that typically last for ninety seconds or two minutes. Go through the mirror with Smith and what the uninitiated hear as directionless dirges become addictive plateaus, gentle blizzards you enjoy losing yourself in.

After this, you would expect recovery and return, a compensatory uplift. But in the event The Cure’s season in hell was far from over and Pornography outdoes even Faith for morbid enervation. But Faith’s amorphousness is replaced by a newly jagged abrasion and a jittery rhythmic urgency that was The Cure’s take on the then fashionable tribal sound. Its template seems to be the less synthesizer-heavy, more metallic-brutalist tracks on Closer (‘Atrocity Exhibition’, ‘Colony’); the cavernous hollow spaces of PiL; the dancing in the ruins urban anomie of Killing Joke. In the end, it sounds like ‘Flowers of Romance’ sung by a neurasthenic rather than a hysteric, Killing Joke fed on bad trip acid and downers, a defunked 23 Skidoo, all at once.

The opener, ‘100 Years’, is The Cure’s masterpiece. It starts as it means to go on, Smith intoning, “It doesn’t matter if we all die’, an invitation even more forbidding than that leered by the circus barker Curtis on ‘The Atrocity Exhibition’ (‘This is way step inside…’) Like Joy Division’s ‘Disorder’, ‘100 Years’ seems to lift its head from morbid self-absorption to gaze at the world – its words a Cold War ticker-tape as filtered through an adolescent nervous system in the midst of breakdown - but in reality it only selects for consideration those things which confirm its hypothesis that cosmic despair is the only justifiable attitude. ‘Ambition in the back of a black car…. Sharing the world with slaughtered pigs… The soldiers close in….’ Smith comes on like Bowie’s Newton in the most famous scene of The Man Who Fell to Earth, entranced and stupefied by a bank of television screens, all of them bringing bad news. What makes this exhilarating rather than emiserating is the necrotic urgency of the death-disco drum machine and Smith’s guitar riff, which blazes like a distress flare in light polluted sky.

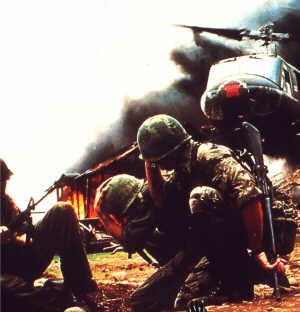

If Smith’s guitar on Pornography often sounds Eastern, it calls up a fantasmatic East in which all of the hippie dreams of free-your-mind exotica have been napalmed into oblivion. Pornography was famously recorded on LSD washed down by alcohol (the band would skulk in a pub waiting for the effects of the acid to wear off before they went into the studio) but it is psychedelic in the same way that Apocalypse Now is. (There are grounds for claiming that Apocalypse Now - with its warporn media overload, its schizophrenic delirium, its sense that The End is only minutes away - was the postpunk film; 23 Skidoo, for one, seemed to have emerged fully-formed from its vision.) Pornography’s delirium is a Jacob’s Ladder bad trip, a psychic Indochina fever dreamt in a Crawley bedroom, the hallucinogens giving distended and distorted shape to anxieties conjured from the suburban heart of darkness.

Smith's lyrics shred sense for the sake of image-impact. He has always been a 'purveyor of filmic ambience' (Bracewell), and the songs on Pornography convey mood through striking images ('voodoo smile... siamese twins') that never cohere into any clear meaning. The album is the Goth equivalent of a chocolate box: an exercise in sheer morbid indulgence unleavened by any cheer.

At the end of the title track, a howling grind that sounds like Joy Division 'The Atrocity Exhibition' spliced with Stockhausen's Hymnen, Smith seeks redemption. ‘I must fight this sickness…. Find a cure….’ But the sickness, the sickness was the most interesting thing about The Cure.