October 29, 2005

soon there will be more reconstructions than things that have actually happened

You wait for one Blissblog post and then seven arrive at once.... Amidst the torrent, Simon draws our attention to Stylus' week-long celebration of ELO. I particularly like this piece by Mike Powell, which argues that ELO and Roxy were the 'warped negative image' of one another. Twiggy and Dervla Kirwan have been given the credit for reviving the market performance of Marks and Spencer, but the use of 'Mr Blue Sky' in the television advertising campaign must have been at least as significant.

Interesting how different what both Roxy and ELO did with Pop time - refracting it, bending it, producing unheimlch PKD-style back-to-the-futures - is to the temporal malaise which Simon rightly identifies as one of the blights on contemporary pop. One of the strongest and most convincing aspects of Jameson's critique of postmodernism was his identification of the exhaustion of a sense of historical time as a defining characteristic of the postmodern. Once, Roxy and ELO might have seemed archetypally postmodern, but their thematization of the looping of Pop time is what is missing amongst much contemporary pop which performs the end of Pop history without being able to comment on it. Was just watching The Armando Iannucci Shows (from 2001) in which Iannucci jokes at one point that soon there will be more reconstructions than things that have actually happened. (Jameson's vast new book, Archaeologies of the Future attempts to reconstruct the future that postmodernism has erased).

Meanwhile - although on the same theme really - Simon's remarks on the Gang of Four revival - particularly the placing of 'We Live as We Dream, Alone' as the final track on the Return the Gift album - take on an added piquancy when you read this, which is way more depressing than Go4 being reduced to re-recording their old songs.

October 28, 2005

The past as a shared dream

The latest Ghost Box release, Mind How You Go by the Advisory Circle, is worth £4.50 of anyone's money. The packaging alone justifies the outlay. The standard elegance of the Ghost Box design is actually heightened by being distilled and miniaturized on a dinky 3" CD. The sounds are the by now familiar-strange Ghost Box signatures: slightly angular analogue synths and a summer haze of voices (lifted from public service films and children's records) benignly conspiring to produce a convivial uneasy listening. The past as a shared dream. 'And the Cuckoo Comes', with its cut-glass intoning of a child's rhyme, is my personal favourite; its faintly sinister refraining reminiscent of the use of nursery lyrics in Sapphire and Steel.

Mind How You Go is available from the Ghost Box website, where you will also be able to find a couple of try-before-you-buy mp3s available for download.

October 27, 2005

Literally thinking outside the soapbox

No apologies for yet another Lenin's Tomb link; this time, Bat on 'a penchant for unexpected dialectical reversals in the normal ideological discourse of consumerism' - namely the recent trend for advertisers to say the opposite of what you'd expect (Persil opining that 'dirt is good'; Orange piously informing us that 'good things happen when your mobile is switched off'.) I'd been vaguely annoyed and bemused by these ads, but had merely attributed their reversals to advertiser smugness. If the Unilever site is to be believed, though, the Persil campaign is an example of 'literally thinking outside the soapbox'.

New Transmat Content

A new book is now online at Transmat. Patricia McCormack#s Pleasure, Perversion and Death deals with Italian gore cinema from a Deleuzoguattarian perspective. (I haven't read it all, but I'm hoping that there's mention of the shark vs zombie scene in Fulci's Zombie Flesh Eaters...)

Also: if people have essays and/ or theses that they think would be appropriate for Transmat (broad remit really: Deleuze-Guattari, cyberculture, Foucault, Lyotard, psychoanalysis, post-structuralism, postmodernism etc etc) they should email Transmatmail[at]gmail.com.

October 25, 2005

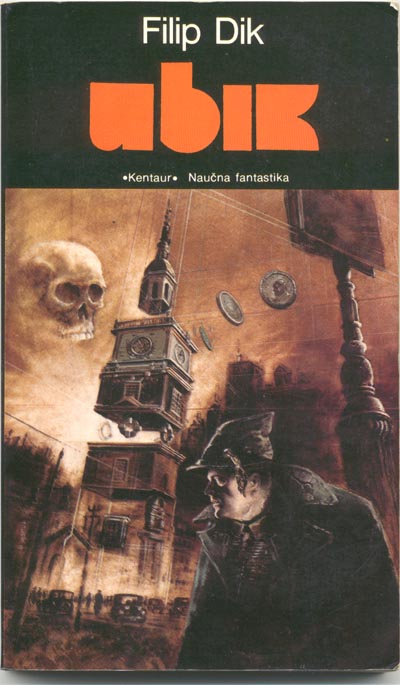

Ubik as petit objet a

'He wondered how much difference Ubik – dangled towards them again and again and again in countless different ways but always out of reach – would have made.'

- Philip K Dick, Ubik

Everyone knows that the moment of vertigo in a Philip K Dick novel occurs not when one level of reality has been exposed as fake, but when the second level, the supposedly more real level, turns out to be inauthentic too. Here, we move beyond the familiar sense that 'things are not as they seem' to a mis en abyme in which, by implication, the status of reality as such is undermined. Dick's signature concept is not the notion that this or that reality is fake but the idea that any reality whatsoever is false.

Steven Shaviro explains that '[f]or Dick, Being is not a plenitude. It is always somehow fake, or trashy, or incomplete, or unstable or radically inconsistent. And Dick's novels describe, in excruciating detail, the lived experience of this unreality, or not-quite reality, that is not yet simply absence or nonexistence'. These experiences are not a consequence of finding oneself in a particular, low-grade reality; rather, they follow from living in any reality, which will be experienced as seedy and second-rate simply because one lives in it.

Dick's novels, then, are a sustained meditation on the difference between reality and the Real. Reality is what is available to us as possible experience in any lifeworld. The Real, however, is what has to be in place so reality can function, the 'something else' that must be presupposed in order that we can experience anything at all. Yet this hyper-structure is not evident insofar as it undergirds or guarantees experience, but only where it fails to do so: in the gaps, fissures and ruptures in reality. The Real is the trauma around which reality is structured; although it is not possible to experience it as such or 'in-itself' (The Real is impossible...) its effects can be felt through 'ripples of distortion' in the structure of reality (... but it happens). As Zizek puts it in Plague of Fantasies, reality is 'what constitutes reality is the minimum of idealization the subject needs in order to sustain the horror of the Real.' (66)

In Ubik Joe Chip's reality famously corrodes, devolves, falls prey to the entropy that is one of the ruling forces in Dick's cosmos (and ours). Everything he touches decays and collapses; cigarettes turn stale in the pack, milk instantly sours. (It's tempting to read Ubik as an account of depression, a condition which similarly devivifies everything with which it comes into contact. In fact, of course, Ubik probably draws heavily on Dick's experiences with speed come-downs.) As all heat passes from Joe and he becomes pure weight (remember the horrifying slow motion climb up the stairs, his body by now a barely movable bulk oppressed by a hideous gravity), he is rescued by the spraying of an aersol can of Ubik, the all-purpose 'reality support' which now begins to appear - fleetingly and tantalisingly – everywhere. (The novel, with its quest form, its magical objects, its benevolent and malevolent messages from those supposed to know - Runciter, Elly, Jory - is like a computer game programmed by a Lacanian.) Joe's quest for the Holy Grail of Ubik faces multiple, bad dream frustrations – the worse being when the can is regressed to an earlier mode so that it becomes useless. Looking at what is now a tin of liver balm, Joe reflects mordantly on the cheerless irony that a solution to temporal regression has itself been devolved into an earlier form of itself.

What is Ubik - that which is 'dangled towards [us] again and again and again in countless different ways but [which remains] always out of reach' - if not the petit objet a? Ubik, which appears in the narrative (and in the ad-parody epigraphs of each chapter) as a diversity of commodities, seems to promise fullness, a being restored to plenitude. And Joe is apparently blocked from this fullness only by particular contingent facts: the shop is closed, they are out of stock etc etc. Like the objet a, Ubik is both a gap in the reality structure (pointing to 'something else', a beyond, an alternative to shoddiness and seediness) but also a 'reality support' (that which literally 'keeps us going', keeps us wanting).

October 24, 2005

We would have full enjoyment, if only...

Lenin, again on endemic and worsening poverty in the USA. But even after Katrina has exposed the reality of America's internal Third World, the fundamental fantasy of the US Right remains robustly in place. In Lacanian terms, a subject's fundamental fantasy takes the form of a statement of this type: 'I would have had access to enjoyment if only X hadn't stolen it from me'. The US version of this is a slight variation: 'we Americans have full access to enjoyment, but we are preventing from experiencing it because others want to steal it from us' or 'our access to full enjoyment is blocked only by those others who resentfully pretend that we don't have such access.' In this fantasy, Americans are positive, optimistic, while the Other - 'Old' Europe and/ or 'Islamofascists', or their supposed fusion in 'Eurabia' - is negative, embittered, backward-looking. One of the most baffling and infuriating aspects of those who fall victim to the fantasy is their absolute conviction that, in their heart, everyone wants to be American. I'm sure that the disaster in Iraq is in part a consequence of this fantasmatic conviction. It is not so much that the Bush regime failed to think about how to deal with resistance to American occupation; it is that such resistance was for it at the time unthinkable. The expectation was that the US Army would be warmly greeted by all Iraqis, proclaiming: 'yes, bring us your 60 hour working weeks, your pornography, your spiralling debts, your obesity and heart disease, give us it now, it's what we have always wanted...'

October 23, 2005

The Subject Supposed to Loot and Rape

Lenin brilliant on Zizek's new piece on the extraordinary outbreak of racist hysteria in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

ITN was certainly guilty of propagating the delirium. The most shameful moment came when they led their bulletins with a 'story' in which a couple of gap-year idiots gave their 'insights' into the 'horror' of the Superdome. The story exemplified the media tendency to equivocate between the phobic phantasms of white tourists and actual empirical events. The 'shocking footage' of the Superdome that ITN promised actually amounted to fuzzy video shot by the tourists, which showed precisely nothing to substantiate any of the claims about Hobbesian outbreaks of orgiastic violence - appropriately, it was a 'blank slate' to be filled in by the (racist) imagination of the viewers. Needless to say, the British tourists' brief sojourn in the underclass Hell that many of the New Orleans black poor will spend all of their life in was quickly over, their attempts to have a cheap holiday in other people's misery frustrated; they were given preferential treatment (a possible source of the hostility of which they claimed to be a victim) and soon escaped the city.

Zizek's point is that, even if some rapes happened, that wouldn't have stopped the coverage being racist. It's a point he's made before, in relation to the Nazi treatment of Jews: to undertake an empirical survey to determine if there was any factual basis for the Nazis' claims about Jewish conspiracies would be grotesque, because 'even if rich Jews in early 1930s Germany “really” had exploited German workers, seduced their daughters and dominated the popular press, the Nazis ’ anti-Semitism would still have been an emphatically “untrue,” pathological ideological condition. Why? Because the causes of all social antagonisms were projected onto the “Jew”—an object of perverted love-hatred, a spectral figure of mixed fascination and disgust.'

Lenin is right to say that the same process is happening with the Pro-Bombing camp's demonization of Muslims. Actual criminal acts by particular Muslims become the empirical justification for racist meta-narratives about 'bad men in turbans'. As Lenin observes (in the comments box) in relation to the Pro-Bombing 'Left', 'It isn't that they deep in their hearts are dirty racists, although performatively that is what they have become: it is that they have internalised the priorities of power, and therefore have come to believe that the US and Israel are unfairly maligned while a cluster of radicalised Muslims are being whitewashed by the liberal media. They have no idea how far to the right they are in that respect, of course.'

October 21, 2005

I filmed it so I didn't have to remember it myself

I was reminded of A History of Violence while watching Andrew Jarecki's ultra-disturbing documentary Capturing the Friedmans on C4's new digital service, more4, the other night.

Capturing the Friedmans is about a family from Great Neck, New York State, two of whose members (the father, Arnold, and one of the sons, Jesse, then only a teenager) pleaded guilty to serious sexual offences and were consequently jailed. Were they guilty? We can be reasonably confident only that Arnold had paedophiliac tendencies, and owned child pornography; he also confessed to having had some sort of sexual contact, short of sodomy, with two boys, but not in Great Neck. The rest is an enigma which makes Rashomon seem like an open and shut case. Jesse's role, for instance, is desperately unclear. The supposed victims claimed that Jesse had participated in, and assisted with, his father's violent abuses. But a campaigner cast doubt on the victims' testimony, none of which was corroborated by any physical evidence, and most of which seemed to have been 'recovered' after they had been hypnotized.

The gaps in the Friedman narrative are all the more glaring because of the plethora of recorded material that IS available. This was a family that seemed - like many now I suppose - to obsessively record itself. Part of the 'capturing' of the Friedmans is their capturing of themselves, on film and on tape. A documentary like this only became possible now that filming technology - cine cameras and later camcorders - had become widely available for the first time and kids are filmed from the moment of birth. The whole thing felt like a grim counterpoint to the proto-reality TV documentary of the Loud family Baudrillard discussed in 'Precession of Simulacra'. In a way, the most painful material consists of home movie footage of the Friedmans shot in the 1970s, in which they look for all the world like a perfectly happy family, the kids mugging and clowning for the cameras. Never has Deleuze's observation that 'family photos' are, by their very nature, profoundly misleading been more bitterly borne out. Later, as the trials start and the recriminations follow, the family fimed and audio-taped themselves ripping each other to shreds.

Why did they continue to film? 'How do they remember, those who do not film?' asks Chris Marker in Sans Soleil. But why would the Friedmans want to remember their journey into Hell? Who could possibly want to film this? In Lost Highway Fred Madison (Bill Pullman) claimed that he hated the thought of video-taping his own life because he 'liked to remember things in his own way'. In an uncanny complement to this, David Friedman, who recorded the events of the day Jesse was sentenced to 18 years imprisonment, said that he filmed 'so I didn't have to remember it myself'. The machines remember, so we don't have to.

October 20, 2005

Anomalous superficiality

Hey! Old skool-style inter-blog bizniz; Jodi answers my objections to her reading of A History of Violence and now Steven Shaviro weighs in with what may turn out to be the definitive account.

Jodi complains that I have failed to take account of her acknowledgement that the Gangster elements of the film are no less real than the Family scenes. On the contrary, I think that it is her reading which contradicts that acknowledgement, and must do. I accept that, explicitly, she concedes that the Family reality has no ontological priority over the Gangster. But the point is that her interpretation of the film depends upon a clear implication inconsistent with that awareness. To say that the film is the son, Jack's, fantasy is, surely, to say that the entire Gangster plot is the product of his psychological conflicts. How could this not be treating Jack - and by extension the Family/ melodrama generic elements - as more 'basic', i.e. more real, than the Gangster generic elements? On this model, Jack's psychology is a stablizing epistemological baseline to which everything in the film can be indexed. Yet there seems to me to be no warrant in the film for such a privileging. On the contrary, what is remarkable about A History of Violence is its refusal of the possibility of this kind of hierarchical settling. Jack's psychological conflicts and 'struggles with manhood' are every bit as cliched as the hyperbolic violence of the Joey plot. To treat the Melodrama conventions as generative of the Gangster conventions is not only arbitrary, it misses what is most troubling, and most distinctive, about the film's ontological disturbances, which amount to a kind of Escherizing of genre.

A History of Violence is characterized by what we might call an anomalous superficiality. The film is pure surface, or rather, pure surfaces, limned together in such a way that we are aware of a structural inconsistency but are unable to 'see the joins'. The seamlessness of which I wrote in my last post is the seamlessness of the moebian band, about which Steven writes so well:

'At any given point, it seems to have two sides; but the two sides are really the same side, each is continuous with the other, and slides imperceptibly into the other. There is no way to separate the Capra/Spielberg side from the noir/revenge nocturnal side. The common interpretive tendency in cases like this is to see the ‘dark’ side as the deep, hidden underside of the ‘bright’ side, the depths beneath the seemingly cheerful surface. But in A History of Violence, everything is what it seems. Both sides, both identities, are surfaces; both are ’superficial’; and they blends into one other almost without our noticing. The small town, with its overly ostentatious friendliness, is a vision of the good life; but brother Richie’s enormous mansion, furnished with a nouveau-riche vulgarity that almost recalls Donald Trump’s penthouse, is also a vision of the good life.'

An important point here being that Trump's own penthouse - in 'real life' - is itself, of course, a fantasy, but so is small town family life. It, too, is a matter of actors occupying a stage-set. America, as Baudrillard, following Dick and Ballard, long ago realised is itself, in its 'actual reality', an assemblage of incommensurable 'reality options' given an illusory but performatively effective consistency only by fantasy. Yet fantasy precisely has no origin in interiority; on the contrary, all seeming interiority is the playing out of fantasies that are intrinsically social. Furthermore, it is not only that, as Steven rightly insists, cinematic fantasies are social; it is also that social fantasies are now deeply cinematic.

Hence to see the film as the playing out of our fantasies is at the same time to see ourselves as the playing out of fantasies which belong to no-one, which cannot be routed in any Inside. Jodi is right that this is to void any interpretation confined to the film's 'content'. Again, though, this is the point. For psychological interpretations not only privilege a particular psychology within the diegesis; they also privilege the epistemological over the ontological. A History of Violence, however, is a film which goes out of its way to expose the way in which genre is ontology, and demands that we pose to ourselves the question of our libidinal complicity in the realities cinema constructs. It is a film which invites us to confront the radical inconsistency of 'our' fantasmatic constructions and of our libidinal investments. Our desire for the family idyll is what produces our cheering for Jack and Tom's recourse to ultraviolence when that idyll is threatened, and this complicity is the 'glue' which joins the two 'sides' of the moebian band - the Capra/ Spielberg and the noir/ revenge worlds - together in a seamless loop. A film reduced to Jack's psychological conflicts could safely be externalized, but if we ourselves are Tom-Joey - animals with a taste for violence hiding in a simulation of domesticity - then the film has forced us to confront the flimsiness of the film sets we inhabit. A History of Violence would then belong to a kind of meta-generic ontological uncanny which performs that destruction of the homely that the Situationists were so fond of invoking.

'The show is over. The audience get up to leave their seats. Time to collect their coats and go home. They turn around…no more coats and no more home.' –Vasily Vasileyevich Rozanov, The Apocalypse of Our Time

October 18, 2005

A seamless tissue of fantasies

Jodi Dean has an interesting reading of A History of Violence that is contrary to mine. She interprets the film as 'the son's fantasy of violence underlying the passive, ordinary goodness of his father'. (The son, as Jodi rightly says, was entirely absent from my account of the film). For Jodi, the film is a coming-of-age drama of an aberrant kind, in which, only by splitting 'the father into the good father of the symbolic and the obscene father of the mob, of underworld violence' can 'the son ... grapple with his own dilemmas of becoming a man.'

Ingenious as this reading is, I find it unsatisfactory for a number of reasons. First of all, A History of Violenc frustrates an 'epistemological' interpretation of this type at every turn. It is not a film like Fight Club, Memento and The Machinist, i.e. an enigma which resolves into questions of epistemological motivation. In those films, once we realise that what we have seen is the product of a psychiatrically and/or neurologically disordered mind, everything falls into place. They are jigsaw puzzles which can be put together, and Sense can be restored. A History of Violence, by contrast, is closer to Mulholland Drive and Eyes Wide Shut, films which scramble Sense and leave it scrambled. Appearances to the contrary, there is no moment of ultimate revelation in A History of Violence. The revelation at the level of diegesis - our discovery that Tom is Joey - does nothing to resolve the film's most troubling quandary, which is ontological rather than epistemological. At the end, nothing makes sense, because the questions the film has raised - not only 'what here is real?', but, more profoundly, 'what is (the) Real'? - have not been settled.

Part of the problem with Jodi's reading is that there is no clear ontological hierarchy in A History of Violence. Nothing is 'marked' as more real than anything else. This, again, is by contrast with Fight Club or The Machinist, which turn upon a discrepancy - concealed in the early parts of the films, but exposed by their end - between the psychotic delirium of the lead characters and a publicly-validated empirical reality. But there is no such discrepancy in A History of Violence, largely because there is no uncontested, convincing, empirical reality from which we can clearly differentiate the fantasmatic elements; there is only a seamless tissue of fantasies.

This is what makes the superficially conventional A History of Violence more ontologically unsettling than something like Existenz. Existenz presents a 'embedded' ontological hierarchy, in which different realities are contained within each other, the 'most real' being the one that embeds the rest. By the end of Existenz, this hierarchy has been disrupted, first, by the 'reality bleed' between ontological levels, so that supposedly 'inferior' realities come to contaminate 'superior', higher-level realities, and second, by the suggestion of an infinite regress of realities, with no ground level. A History of Violence gets to this sense of groundlessness or 'abgrund' without recourse to a 'vertical' model of nested realities. Realities are not placed one inside the other, but juxtaposed, one next to the other. A different kind of 'reality bleed' altogether.

As Jodi rightly observes, 'When we first see [the son] he is part of a completely fantastic image of the perfect family: the teenage son concerned about his little sister's bad dream.' This, then, would appear not to be 'real'. But what is? There is barely one situation in which the son finds himself that is not equally implausible: his verbal and then physical besting of the bully, like his shooting of the gangster to save his father's life, seem 'obviously' fantasmatic. But, then, so does everything else in the film. Jodi might argue that the film's 'real Real' is what is not depicted at the level of its diegesis - yet, her reading, of necessity, relies on privileging certain elements of what we DO see (most obviously, we have to accept that the son really is a son, really is at high school etc etc).

Jodi's reading also surreptitiously resolves the film's ontological tension, by assuming that the 'Joey reality' is ontologically inferior to the 'Tom reality'. On what grounds, though? As Jodi herself notes, the Stall domestic Paradiso is no more 'real'(istic) than the organized crime Inferno; it is just that, in the first case, the fantasies derive from melodrama, while in the second, they are taken from the gangster genre. (In this respect, A History of Violence can be compared with The Shining, which similarly mediates between the conventions of family drama and those of another genre, in that case, Horror. See Walter Metz's intertextual analysis here.) Paradoxically, the Stall family only seems realistic once it is menaced by mobsters who are no more realistic. If there is 'realism' at all, it is generated by the tensions between the conventions of two genres.

Jodi says that my reading was too quick to remove fantasy. But I would want to argue that Jodi, like Graham Fuller in Sight and Sound, contains fantasy by giving it a diegetic motivation. What this leaves out is in a way the most obvious fantasmatic level: that of our own fantasies. It is not that the events of the film can be reduced to the fantasy of one of the characters; no, the film forces us to confront the way in which the characters are OUR fantasies, the violence is the violence of OUR wish fulfillments.

Which is why I wholeheartedly concur with Jonathan Rosenbaum (via).

'There's hardly a shot, setting, character, line of dialogue, or piece of action in A History of Violence that can't be seen as some sort of cliche,' he writes. 'Its fantasies about how American small towns are paradise and big cities are hell are genre standbys that Cronenberg milks at every turn. But none of this plays like cliche; Cronenberg is such an uncommon master of tone that we're in a state of denial about our familiarity with the material -- a kind of willed innocence that resembles Tom Stall's own disavowals.'

October 11, 2005

The dark is in my mouth, and I suck it.. it's the only thing I have...

Watching Last Year in Marienbad last week, I was reminded of Pinter. So much of the dialogue in Marienbad functions as a kind of sorcerous incantation, a command, an attempt to issue what Deleuze-Guattari call 'order words'. There is the sense that the words do not merely describe, or describe at all, but possess an illocutionary force, a capacity to make things happen through their very utterance. As in so many of Pinter's plays, the characters - the male character referred to as 'X' in the script and the female character called 'A' (for 'Autre'?) - are fighting over the past, he by constructing it through words, she by never fully succumbing to the word-world he conjures. When X makes such statements as, 'we kept meeting each other at each turn in the path behind each bush -- at the foot of each statue -- at the rim of every pond' , our suspicion is that he is manufacturing these 'memories' as he speaks, through his speech, but part of what makes the film so haunting is that neither Robbe-Grillet's writing nor Resnais' direction confirm or deny that intuition.

Pinter's plays were always, famously, about territorial struggle, but the territory being contested was as much in time as space. (Lorenz plus Proust?) His first play, The Birthday Party, is a rendition of the relatively conventional theme of unsuccessful re-invention and of failed repression of the Past. But as his plays progress, the Past, the 'Old Times' that lend one of them its title, become more mutable, elusive, contested. The Past is not to be repressed, or hidden, but continually re-invented. It is the site of the struggle in the wintry existential comedy of his masterpiece, the claustrophobic, uncomfortably hilarious, No Man's Land in which two old men who may once have been acquaintances, even friends, or who may never have met before, attempt to cast each other as bit parts in their own continually confabulated Memories. I think - or perhaps I am misremembering - that it is Pat Cadigan who somewhere observes 'that the future is fixed, only the past can be changed.' That could be the slogan for so much of Pinter's work, in which characters stalk each other, waiting, waiting, for the moment in which they will be able to trap their antagonist into their version of the past.

These observations were partly prompted by the broadcast tonight of Pinter's 'new' play, Voices. Strictly speaking, Voices is neither new nor a play so much as a kind of 'unreliable memory' of Pinter's last five dramatic works plays (One for the Road, Mountain Language, The New World Order, Party Time and Ashes to Ashes) in the form of a sonic delirium. Voices is a collaboration with composer James Clarke, but it is much more than a matter of accompanying Pinter's words with music. Drama, in the sense of tension and/ or narrative, is in fact entirely suspended, consumed by the agitated stillness of Clarke's antarctic radiophonic score, every bit as understated and starkly beautiful as Pinter's dialogue. Clarke does not set Pinter's words to music, he draws out their already highly musical rhythms in order to treat de-contextualized phrases from the plays as sonorous components in a minimal sound-mosaic.

Like many, I found the apparent didactism of Pinter's last plays a little lacking in the enigmatic poetry that made the earlier works so compelling. Perhaps that judgement is too peremptory, and the newer plays' apparent break from his earlier methods will appear less decisive as time moves on. As a re-mixing, an auto-sampling of those later plays, Voices may play a significant role in any such re-appraisal. By subtracting context, Voices restores enigma, but in a way heightens the political impact of the words, these words about language that is forbidden, language that is forced...

'Where are you now? Do you think you are in a hospital? ... Have they raped you? How many times?' Pinter's torturer asks an unnamed woman in a section sampled from One for the Road (the last Pinter play I unequivocally enjoyed, if that is the right term for what is a deeply harrowing experience). These are of course not genuine questions, nor even interrogator's enquiries. The torture partly consists in being forced to acknowledge the torture, to bring into the symbolic order that which ought to remain unsymbolizable. She must be made to recognize that she is here, now, in an non-place that is the very opposite of a utopia, a place that is without protection, without hope, beyond the purview of any possible justice, a place where only the Night Law holds sway... What makes this all the more horrifying is the clear implication - which the torturer Nicholas takes great delight in spelling this out to his victims - that this Underworld, this Hell is not some private pervert's lair, some secret, unsanctioned Evil, but the obscene supplement of the Official Law, what it requires in order to function. 'They' know what is happening, but they will not come, as your name, your past, everything you are and everything you have been, are stripped away... For this is Hell, and nothing, nothing is more Real...

There's an interview with Pinter and Clarke in the Independent here, but, even better, if you go here, you will be able to hear Voices. I'm just listening to it for the third consecutive time. It feels like an infernal loop, a Terror I'm compelled to keep repeating...

October 04, 2005

Corridors in which time is abolished: notes on Last Year in Marienbad

We find ourselves in an endless loop, let's call it a film.

When we come in, it has already started.... Some acousmatic sleeptalk, fitfully legible, is already babbling.... we attribute it, almost certainly mistakenly, to someone that we later learn - though not while we are watching - is called 'X'... ('X' is not a person, surely?)

We have been warned. Psychology is the great temptation to be resisted. We must not ask who the couple are, or speculate as to whether they 'really' met last year, whether they were 'really' lovers. Such questions lead nowhere, and are missing the point.

We must not look for hidden depths, either. There are no depths here, the effect of depth is an illusion to which we must learn not to succumb. If there are things hidden, they must have been secreted here on the surface. But these are surfaces so densely detailed, so artfully posed and poised, so doubled and redoubled in reflections (of reflections [...]) that it would be easy to hide almost anything on them.

There are clues everywhere - many of the hotel guests stand, fixated, rapt, in front of a map of a labyrinth - but aren't they telling us that this is an enigma that there is no solving?

The effigies here - they seem to resemble human beings, and how can we not be reminded of the marionette trance of the waltzers in Poe's 'Masque of the Red Death'? - are the opposite of Deleuzian nonorganic life. They are devitalized organisms, which we are invited to compare with the marbled frigidity of the statues in the gardens. Becoming is denied them. They are themselves closed loops, a finite set of permutations (like the diabolic-erotic machine dreamt of by Villiers de L'isle Adam in The Future Eve), recordings played by the hotel itself, perhaps...

It's a perfume commercial as film, fashion shoot as hauntology, a feature dreamt out of the future reveries of H. Newton....

There is sequence here, but no duration.

How to account for the space and time lacunae? Perhaps some Thing traumatic has happened, perhaps this whole ornate, baroque structure has been constructed around the denial of that Thing?

Some see the human figures as mere simulacra, finding the key to the labyrinth in which they are lost in Adolfo Bioy Casares' The Invention of Morel. If this is so, then we would in the midst of the first of a 'flood of ontological vertigo films' since, in Casares' novella, 'It turns out that Morel's invention is a diabolical holographic recording device that captures all of the senses in three dimensions. It is diabolical because it destroys its subject in the recording process, rotting the skin and flesh off of its bones, thus gruesomely confirming the native fear of being photographed and also, perhaps, warning of the dangers of art holding up a mirror to nature.'

In these corridors in which time is abolished, in these sumptuous corridors we survey with long, unhurried tracking shots, there are anticipations of other houses, other hotels. 'Resnais' ...vast hotel of the memory and imagination and its lovers in L'Annee derniere ... plays its part in the presentation of the Overlook.'

... and is it fanciful to see echoes here of Mandalay? Place of endless returning, spectral shades....'Last night I dreamt....'

|  |

Labyrinths don't have meanings. You either traverse them, or you remain lost within them ...

October 01, 2005

When we dream, do we dream we're Joey?

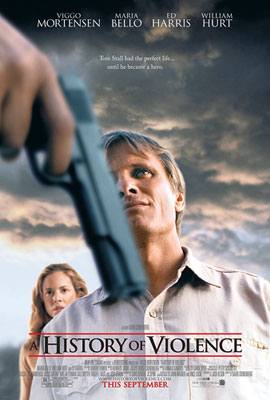

'When you dream, do you dream you're Joey'? - Carl Fogarty to Tom Stall, in A History of Violence

'In a dream he is a butterfly. ... When Choang-tsu wakes up, he may ask himself whether it is not the butterfly who dreams that he is Choang-tsu. Indeed he is right, and doubly so, first because it proves he is not mad, he does not regard himself as fully identical with Choang-tsu and, secondly, because he doesn't fully understand how right he is. In fact, it is when he was the butterfly that he apprehended one of the roots of his identity - that he was, and is, in his essence, that butterfly who paints himself with his own colours - and it is because of this that, in the last resort, he is Choang-tsu.' - Lacan, 'The Split Between the Eye and the Gaze', The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis

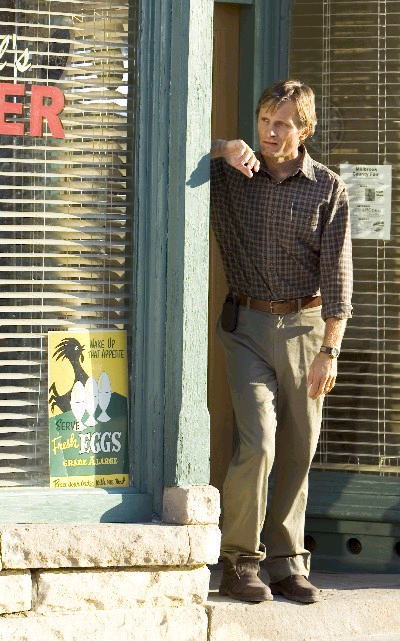

The key scene in Cronenberg's A History of Violence sees the local sheriff addressing the hero, Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen), after a series of violent killings have disrupted the life of the small midwest town in which they both live: 'It just doesn't all add up.'

Superficially, A History of Violence is Cronenberg's most accessible film since 1983's The Dead Zone. Yet it is a film whose surface plausiblity doesn't quite cohere. All the pieces are there but, when you look closely, they can't be made to fit together. Something sticks out....

What makes A History of Violence unsettling to the last is its uneasy relationship to genre: is it a thriller, a family drama, a bleak comedy, or a trans-generic allegory ('the Bush administration's foreign policy based upon a western')? This generic hesitation means that it is a film suffused with the uncanny. Even when the standard motions of the thriller or the family drama are gone through, there is something awry, so that A History of Violence views like like a thriller assembled by a psychotic, someone who has learned the conventions of the genre off by heart but who can't make them work. Perversely, but appropriately for a Cronenberg picture, it is this 'not quite working' that makes the film so gripping.

The near total absence of the prosthetics and FX for which Cronenberg is renowned from A History of Violence (traces of his old schtick survive only in the excessive shots of corpses after they have been shot in the face) has been remarked upon by most critics. In fact, Cronenberg's renunciation of such imagery has been a gradual process, dating back at least as far as Crash (1998's Existenz may turn out to be the last hurrah for Cronenberg's pulsating, eroticized bio-machinery), but it has subtlized, rather than removed, his trademark ontological queasiness.

Myth is everywhere in A History of Violence: not only in the hoaky small-town normality which is threatened, nor in the urban underworld of organized crime that threatens to encroach upon it and destroy it, but also in the conflict between the two. A town like Millbrook, the Indiana setting for A History of Violence, has been as likely to feature in American cinema as an image of menaced innocence in its own right. Comparisons with Lynch are inevitable, but it is Hitchcock, not Lynch, who is the most compelling parallel. The Hitchcock comparison goes far beyond surface details, significant as they are, such at the fact that, as the Guardian review reminds us, A History of Violence's 'Main Street resembles the one in Phoenix, Arizona, where the real estate office is to be found in Psycho'. There is a much deeper affinity between A History of Violence and Hitchcock which can be readily identified when we recall Zizek's classic analysis of Hitchcock's methodology. In Looking Awry, Zizek compares Hitchcock's 'phallic' montage with the 'anal' montage of conventional cinema.

'Let us take, for example, a scene depicting the isolated home of a rich family encircled by a gang of robbers threatening to attack it; the scene gains enormously in effectiveness if we contrast the idyllic everyday life within the house with the threatening preparations of the criminals outside: if we show in alternation the happy family at dinner, the boisterousness of the children, father's benevolent reprimands, etc., and the "sadistic" smile of a robber, another checking his knife or gun, a third grasping the house's balustrade.

In what would the passage to the "phallic" stage consist? In other words, how would Hitchcock shoot the same scene? The first thing to remark is that the content of this scene does not lend itself to Hitchcockian suspense insofar as it rests upon a simple counterpoint of idyllic interior and threatening exterior. We should therefore transpose this "flat", horizontal doubling of the action onto a vertical level: the menacing horror should be placed outside, next to the idyllic interior but well within it: under it, as its "repressed" underside. Let us imagine, for example, the same happy family dinner shown from the point of view of a rich uncle, their invited guest. In the midst of the dinner, the guest (and together with him ourselves, the public) suddenly "sees too much," observes what he was not supposed to notice, some incongruous detail arousing in him the suspicion that the hosts plan to poison him in order to inherit his fortune. Such a "surplus knowledge" has so to speak an abyssal effect ... the action is in a way redoubled in itself, endlessly reflected as in a double mirror play... things appear in a totally different light, though they stay the same.' (89-90)

What is fascinating about A History of Violence is that it recapitulates this passage from the anal to the phallic within its own narrative development, entirely appropriate for a film that shows, as Graham Fuller puts it, 'the return of the phallus'. It begins, precisely, with a non-Hitchcockian contrast between a threatening Outside (a long, sultry tracking shot of two killers leaving a motel) and an idyllic Inside (the Stalls' family house, where the six-year old daughter is comforted by her parents and her brother after she is woken from a nightmare). But as the film develops, it effectively re-topologizes itself, interiorizing the Threat, or, more accurately, showing that the Outside has always been Inside.

The Hitchcockian blot, the Thing that doesn't fit, is the 'hero' himself. The film's central enigma - is the staid, pacific Tom Stall really the psychopathic assassin Joey Cusack? - can be resolved into the question: which Hitchcock film we are watching? Is A History of Violence a rehashing of The Wrong Man or Shadow of a Doubt? Disturbingly, it turns out that it is both at the same time.

Shadow of a Doubt is the working out of a family scene much like the one described by Zizek above, although in that case, it is the guest, the rich uncle, who is the threat to the domestic idyll. The uncle (Joseph Cotten) is a killer of rich widows who has holed up in the house of his sister's family to hide from the police. The Wrong Man, meanwhile, sees a family destroyed when the father is falsely accused.

In Shadow of a Doubt, the uncle's malevolence means that he must die so that the family idyll can be preserved. Only the Teresa Wright character knows the truth; the rest of the family, and the big Other of the community, are kept in ignorance. But of the family members in A History of Violence, by the end of the film, only the youngest child could plausibly not be aware that the family scene has always been a simulation. Crucial in this respect is the response of Stall's wife, Edie (Maria Bello), as Ballard observed in his piece on A History of Violence in the Guardian:

'A dark pit has opened in the floor of the living room, and she can see the appetite for cruelty and murder that underpins the foundations of her domestic life. Her husband's loving embraces hide brutal reflexes honed by aeons of archaic violence. This is a nightmare replay of The Desperate Hours, where escaping convicts seize a middle-class family in their sedate suburban home - but with the difference that the family must accept that their previous picture of their docile lives was a complete illusion. Now they know the truth and realise who they really are.'

But this isn't so much a matter of accepting reality in the raw, as it were, but, very much to the contrary, it is a question of accepting that the only liveable reality is a simulation. Where at the start of the film, Edie play acts the role of a cheerleader for Tom's sexual delectation, by the end she is playacting for real. (And of course, of course.... there are no authentic cheerleaders, 'real' cheerleaders are themselves playing a role.) If, as Zizek argued in Welcome to the Desert of the Real, 9/11 was already a recapitulation of the 'ultimate American paranoiac fantasy ... of an individual living in a small idyllic ... city, a consumerist paradise, who suddenly starts to suspect that the world he lives in is a fake', a kind of real life staging of The Matrix, then A History of Violence may be the first post 9/11 film in which the American idyll is deliberately and knowingly re-constructed AS simulation. (This is underscored by the fact that not one frame of the film was shot in America. In this respect, the film resembles Kubrick's Lolita, whose America of motels and dusty highways was entirely reconstructed in Britain. In his interview with Salon.com, Cronenberg pronounced himself proud of his ability to hoodwink American audiences into believing that they were really seeing the midwest and Philadelphia.)

'When you dream, do you dream you're Joey?' the mobster Fogarty (Ed Harris) asks Tom Stall, perhaps deliberately echoing Chuang Tzu's story of a man who dreamt he was a butterfly. Chuang Tzu famously no longer knows if he is a butterfly dreaming that he was Chuang Tzu or Chuang Tzu dreaming that he is a butterfly. Is Tom Stall the dream of Joey Cusack, or is Joey Cusack the bad dream of Tom Stall? It's no surprise that Lacan should have fixed upon this story, and Forgarty's question contains an analyst's assumption: the reality of Tom lies not at the level of the everyday-empirical but at the level of desire. The Real of Stall/Cusack is to be found, fittingly, in the desert, the space of subjective destitution where Stall says that he 'killed Joey'.

In an interesting but ultimately unconvincing piece in Sight and Sound, Graham Fuller argues that we should read the film as Stall's fantasy:

'"Who is Joey Cusack?" the movie ponders at its midpoint as it leaves Western territory behind and plunges into a dark pool of noir. But the more fruitful question is "Who is Tom Stall, if not whom Fogarty claims he is, and why does he have a superegoic alter ego?" The name "Stall" indicates stasis. Though he is a diligent, caring husband and father, Tom knows he hasn't made much of himself in life, and, we learn, harbours resentment towards his estranged wealthy brother, who considers him a fool. This chip on Tom's shoulder explains his daydreaming which, born of repression, aligns him which such literary and movie dreamers as Walter Mitty and Billy Liar, whose fantasies of themselves as all-conquering heroes are redolent of crippling neuroses, even impotence...'

Tempting as it is, this interpretation is unsatisfactory for a number of reasons. It is guilty of the same 'oneiric derealization' which has blighted responses to both Lynch's Mulholland Drive and Kubricks's Eyes Wide Shut, both of which have been interpreted as long dream sequences. Such readings ultimately amount to an attempt to put to rest the films' ontological threat, ironing out all their anomalies by attributing them to an interiorized delirium. The problem is that this denies both the libidinal reality of dreams - we wake ourselves from dreams, Lacan suggests, in order to flee the Real of our desires - at the same time as it ignores the way in which ordinary, everyday reality is dependent for its consistency on fantasy. It also makes the empiricist presupposition that the quotidian and the banal have more reality than violence; the message of the film is rather that the two are inextricable.

In the end, Stall as the fantasy of Cusack is much more interesting than Cusack as the fantasy of Stall. Is the American small-town idyll the fantasy of a psychopath? After Guantanamo Bay, after Abu Graib, this question has a special piquancy. The challenge that A History of Violence poses to the audience comes from the fact that we fully identify with Stall/ Joey's violence. We gain enormous enjoyment when the hoods are dispatched with maximum efficiency. When we dream, do we dream we're Joey? Do we dream as Joey? Do we dream of being Tom, innocent, regular people, no blood on our hands? Are our 'real', everyday lives really only this dream?

At the same time as we enjoy Joey's hyperviolent killing of the gangsters, we know that it is impossible for us to position them as the Outside and Stall/ Joey as the Inside, and the film reinforces the lesson that Zizek thought we should have learned in the aftermath of 9/11. 'Whenever we encounter such a purely evil Outside, we should gather the courage to endorse the Hegelian lesson: in this pure Outside, we should recognize the distilled version of our own essence. For the last five centuries, the (relative) prosperity and peace of the "civilized" West was bought by the export of ruthless violence and destruction into the "barbarian" Outside: the long story from the conquest of America to the slaughter in Congo.'

The most disturbing aspect about the film's violence is not the gore that results from it, but the reptilian mechanism of its execution. There are no wisecracking one-liners; instead, once the killings are completed with a coiled spring autonomic power, there is an entranced animal calm, a machine exhaustion. (A History of Violence is reflexive without ironic, entirely lacking in any PoMo swagger. It may have put the final bullet into Tarantino's career, if the spectacular indulgence of Kill Bill didn't already do that.)

A History of Violence suggests that 21C America is a less a country in which violence is a repressed underside than that it is moebian band where if you begin with ultraviolence you will eventually end up with homely banality, and vice versa. In the final scene, when Tom - now 'Tom' - returns to his house, 'everything appears in a totally different light, though it has stayed the same'. The images of domesticity have now become 'images of domesticity', the meat loaf and the mashed potato have become 'meat loaf' and 'mashed potato', reflexively-placed icons of American normality, the very defintion of the unhomely, the unheimlich, the uncanny. Such, as Zizek said in the 9/11 piece, is the nature of 'late capitalist consumerist society' where '"real social life" itself somehow acquires the features of a staged fake'. This is a simulated scenario far bleaker than that of The Truman Show or Dick's 'Time Out of Joint', since it has been freely and knowingly embraced by the subjects themselves. There is no Them behind the scenes orchestrating and choreographing the simulation. At the end of the film, everyone is fooling but no-one is fooled.