June 28, 2009

'... and when the groove is dead and gone...'

|  |

What's haunting me, as I watch all the Michael Jackson videos on constant rerun on the music channels, as I listen to the chat of people on benches and in cafes, all of us going through the now well-rehearsed routines of mass-mediated death, but this time, it's not like the consensual narcissism of the Diana faux-mourning, it's shocked grieving for our real royalty, the prince of our deeply mediatized unconscious... what's haunting me is the difference between Jackson in the Off The Wall videos and how he looks in the Thriller clips. I'm not talking about the surgery, or rather I'm not only talking about that. The surgery - by then, 'only' a Disney eye-widening, a Diana Ross nose-narrowing, and a little skin-bleaching, as nothing compared to the collapsing Cronenbergian butchery of later years - is but a symptom of the change that you can see in Jackson's face and body. Something had already disappeared that early, never to return.

The death of this King - "my brother, the Legendary King Of Pop", as Jermaine Jackson described him in his press conference, as if giving Michael his formal title - recalls not the Diana carcrash, but the sad slump of Elvis from catatonic narcosis into the long good night. Perhaps it was only Elvis who managed to insinuate himself into practically every living human being's body and dreams to the same degree that Jackson did, at the microphysical level of enjoyment as well as at the macro-level of spectacular memeplex. Michael Jackson: a figure so subsumed and consumed by the videodrome that it's scarely possible to think of him as an individual human being at all... because he wasn't of course... becoming videoflesh was the price of immortality, and that meant being dead while still alive, and no-one knew that more than Michael...

Greil Marcus's writing on Jackson - or rather 'Jacksonism' - is some of his most astute commentary on pop and political economy. Lipstick Traces was as much about Restoration, about the Spectacular covering over of the punk event of 76-78 as it was about the event itself, and Marcus very quickly understood the massive role that Jacksonism played in this erasure. A new form of control emerged when shopping malls, VHS videos, charity records and TV commercials became interchangable aspects of the same commodity-media landscape: consensual sentimentality as videodrome. Well, it was new then, all that, but it's very old now, and scarcely visible to us any more now that we have grown habituated to living inside it. It was capitalist realism as entertainment, and we all bought to it, whether we liked it or not:

- Thriller enforced its own reality principle; it was there, part of the every commute, a serenade to every errand, a referent to every purchase, a fact of every life. You didn't have to like it, you only had to acknowledge it.

... By 6 July 1984, when the Jacksons played the first show of their "Victory" tour, in Kansas City, Missouri... Jacksonism had produced a system of commodification so complete that whatever and whoever was admitted to it instantly became a new commodity. People were no longer comsuming commodities as such things are conventionally understood (records, videos, posters, books, magazines, key rings, earrings necklaces pins buttons wigs voice-altering devices Pepsis t-shirts underwear hats scarves gloves jackets - and why were there no jeans called Bille Jeans?); they were consuming their own gestures of consumption. That is, they were consuming not a Tayloristic Michael Jackson, or any licensed facsimile, but themselves. Riding a Mobius strip of pure capitalism, that was the transubstantiation.

The fact that the tour was a commercial failure didn't mean anything; it was a probe-head template for the kind of supermanaged cyberspatial PR pseudo-event hypercommodity that has long since become normalised in what we used to call popular culture. Steven Shaviro points out via email - and I know Steven is working on his own MJ post as I type - that, contra the section of Marcus I recently posted here, "the Beatles were every bit as much about marketing as MJ/Thriller was". Of course this is true, but there was a difference in kind between the Thriller hypermarketing and any previous promotional initiative. The Thriller phenomenon was in fact the first taste of the reality system that has just collapsed. "It was ... a version of what Ulrike Meinhof called Konsumterror - the terrorism of consumption, the fear of not being able to get what is on the market, the agony of being last in line: to be part of social life. All over the country, people became afraid of tickets they could not afford to buy, of tickets they might not be able to buy even if they could afford them, of tickets that would seal them as everything or nothing, of tickets that, as the humiliating, exciting process began, were not even on sale." (Marcus) "An economist from the Motown era time-travelling to present-day Detroit would be faced with a puzzle," Paul Mason writes in Meltdown. "If wages have fallen, then who's buying all the burgers, training shoes, six-packs, televisions and hair extensions that keep this army of low-paid people at work on six to nine dollars an hour? Heny Ford said you couldn't have mass consumption without high wages, so where is the money coming from? The answer is credit: credit cards, shor-term 'payday' loans, zero-percent car finance, low interest rates and self-certified mortgages."

"The Motown sound," Mason argues in Meltdown , "seemed to sum up the deal Henry Ford's system offered the working class: hard work, frenetic leisure and a counter-culture that made everything else look uncool. Above all, it was a world of rising real income. If you work eight hours a day on a production line that does not stop, these three words - 'rising real income' - represent the most important single fact in economics." Up to and including Off The Wall, Michael Jackson's music belonged to that old black dream - music as leisure-convalescence, a utopianism confined to time off work ("gonna leave that 9 to 5 up on the shelf"), with the fortunate few, like Jackson, elevated into superstardom and then - like he and his brothers in the video for the awesome "Can You Feel It" - sprinkling a little stardust on the hardworking black population below.

Off The Wall is still in the grip of Saturday night fever, delirious with all the summer-sweet promise of disco. Here, Quincy Jones and Jackson constructed a song suite that did for late 70s black dance culture what Scott Fitzgerald's novels and stories had done for an earlier, whiter, richer American moment: they shaped the fragile evanescences of youth and dance into beautiful myths, laced with fabulous longings that they could neither contain or exhaust.

The tracks on Off The Wall have an easy disco swagger, which Michael embodies in his dance steps and his grin. The smile may well have been forced, but it doesn't look as if it was. Jackson was at least capable of convincingly simulating (en)joy(ment) at this point. Off The Wall, accordingly, is his masterpiece, the LP-pinnacle of disco, disco as theology, the songs secular hymns to divine disco itself, the impersonal 'force', the inhuman drive, that makes life living but has nothing to do with the vital. Jackson would make better tracks - or one better track, of which more shortly - but none of the LPs, including the largely anodyne Thriller, get even close to Off The Wall. It's a seducer's diary, sung by someone who has himself been ravished, who has given up everything for dance.

"Don't Stop Till You Get Enough" practically leads you by the hand to the dancefloor, the milky-way swirl of the strings sweeping you up, the deliquescing delight ("I'm melting") of Michael's enraptured falsetto gently undoing any resistant character armour. It's a love song to dance itself, just like "Rock With You", which similarly sees the whole universe in a disco mirrorball. "Rock With You" manages the amazing feat of simultaneously bring a tear to the eye and a shuffle to your feet. Jackson comes on as benevolent disco-svengali so he can seduce the listener-girl that the song turns us all into: "Girl, close your eyes/ Let That rhythm get into you/ don't try to fight it" - and who would want to fight it? Listen to the way that the synths and strings suggest starlight seen by starstruck lover's eyes. Is there any record which better captures the cosmic vertigo of falling in love than "Rock With You"? That headlong synaesthetic rush in which music, dancing and love feed each other in a reflexive virtuous circle which, even though it seems miraculous, unbelievable, ("girl, when you dance/ there's a magic that must be love"), at the same time seems like it couldn't possibly end ("And when the groove is dead and gone/ you know that love survives/ and we can rock forever"- ? This was Soul to sell your soul for. No wonder that Green Gartside sacrificed the whole of his avant-garde self in order to sound like this. And if you asked me to choose between Off The Wall and the entire back catalogue of the Sex Pistols and the Beatles, there would be no contest. I respectThe Beatles and the Pistols, but they had already calcified into newsreel-heritage before I even took heed of them; whereas Off The Wall is still vivid, irresistible, sumptuous, teeming with technicolour detail.

Something disappeared after this. It isn't only that Jackson was still a young black man then - and a sexually alluring young black man, with twinkling desire-drunk eyes - rather than the repellent whitened sepulchre he would become a decade later... Think of the creepy video for "The Way You Make Me Feel", Jackson stalking a woman (who by this point it is impossible to believe he would ever want) down a late-night street, looking both sexually aggressive - his disintegrating face now permanently contorted into that pierrot grimace-sneer - and sexually neuter, as if the increasingly absurd performance of peacock-posturing intimidation substitutes for any actual sexual desire. It isn't only that he has not yet become deracinated or desexualised, for deracination and desexualisation might precisely have been refusals of the Restoration's compulsory ethnicity and sexuality, and Jackson could have been a poster boy for queer universality... if his dysphoria, his freakishness, could have found its way into the music. Instead, it was Gothic Oedipus in his (very public) private life dramas, and consensual sentimentality in the saccharine-bland songs. Only in "Scream" and its video - Michael and Janet in a deserted offworld leisure hive that resembles Gibson's incest-Xanadu Villa Straylight - did the music and the crumbling mind ever meet.

But before the Thriller phenomenon encased Jackson in the hypercommodity that he was now reduced to being just a little part of - he would soon be only a biotic component going mad in the middle of a vast multimedia megamachine that bore his name - but before all that was "Billie Jean". "Billie Jean" is not only one of the best singles ever recorded, it is one of the greatest art works of the twentieth century, a multi-levelled sound sculpture whose slinky, synthetic-panther sheen still yields up previously unnoticed details and nuance nearly thirty years on. The only remote parallel I can think of in 80s pop is the sonic architecture that Arif Mardin designed for Chaka Chan on "I Feel For You".

Sometimes, the weariness brought on by hearing it so many times will make you twitch the dial when "Billie Jean" comes on the radio. But let it play, and you're soon bewitched by its drama, seduced into its sonic fictional space, the mean streets and chilly single-parent single-room appartments that now suround the still-glittering dancefloor like conspiring fate. Listening is like stepping onto a conveyor belt. And that's what it sounds like, as the implacable, undulating sinous cakewalk of the synthetic bass takes over the massive space opened up by the crunching snares Jones and Jackson insouciantly hijacked from hiphop. Check, if you can manage to keep focused as the track crawls up your spine and down to your feet, embodying the very compulsion the lyric warns against... check the way that the first sounds you hear from Jackson are not words but inhuman asignifying hiccups and yelps, as if he is gasping for air, or learning to speak English again after some aphasic episode.

Ten years after psychedelic Soul, this is cyborg Soul, with Jackson as cut-up as Grace Jones ever was - partly by the (James) Brownian motion of his own language-disassembling vocal tics (the mirthless, and indeed emotionally unitelligible, joker-hysterical hee-hees, the ooohs shotgun-divorced from doo-wop's street corner community to circulate like disembodied wraithes in the survivalist badlands of an inner city ravaged by Reaganomics), partly by the astonishing arrangement. Check the way that the first string-stabs shadow the track like stalker's footsteps, disappearing into the cold wind like mist and rumour. Feel the tension building in your teeth as the bridge hurtles towards the chorus, begging for a release ("the smell of sweet perfume/ this happened much too soon) that you know will only end in regret, recrimination and humiliation, but which you can't help but want any way, desire so intense it threatens to fragment the psyche, or expose the way that the psyche is always-already split into antagonistic agencies: "just remember to always think twice". Does he then sing "do think twice" or, in an id-exclamation that echoes like a metallic shout in an alley of the mind, "don't think twice"? Everything dissolves into audio-hallucination, the chronology gets confused, the noir string-slivers shiver. Jackson is angry at his accuser (and also at the fans who will trap him into the Image: Billie Jean is pop's Misery) but also weirdly mournful, hunted, pleading (to the big Other, in kettle logic: I didn't do it, I couldn't help it), the part-objects of his voice circling a psyche without a centre. Notice that it's a song about the very things Marcus talks about in Lipstick Traces: seduction by Spectacle, about the way in which everyday life is taunted and haunted by the screen ("she was more like a beauty queen/ from a movie scene"). Billie Jean - which was effortlessly modern, a new Soul that was devoid of any hint of pastiche - could still dramatise all this; perhaps what you can hear is the very process of subsumption itself, Jackson becoming the brand. After this, there would be few glimmers of any outside.

But what had been lost? The Situationist theory that Marcus draws on in Lipstick Traces is informed by a cryto-Bergsonism, a sense that reification consists in the encrustation and calcification of the living body. But what if it weren't a case of the organic being subsumed by the inorganic, but one inorganic being replaced by another? Dancing is always about the death drive, about the libidinal disciplining of the body, about forcing the body into unnatural postures and shapes (when Jackson occasionally amazes after "Billie Jean", it is more likely to be because of his dancing than his singing - the impossible-looking anti-gravity of his literalisation of the gangster lean in the "Smooth Criminal" video for instance). "Every artist," Nietzsche writes in Beyond Good And Evil

- knows how far from the feeling of letting himself go his “most natural” condition is, the free ordering, setting, disposing, shaping in moments of “inspiration”—and how strictly and subtly he obeys at that very moment the thousand-fold laws which make fun of all conceptual formulations precisely because of their hardness and decisiveness (even the firmest idea, by comparison, contains something fluctuating, multiple, ambiguous—).

Dancing is precisely a question of subordinating the body to "arbitrary laws" - and eventually, after the punishing dedication that Jackson put in, that subordination yields an inspiration that grips and micro-directs the body. A different model of freedom emerges here to the neoliberal one, which centres on the "choice" that Jackson promoted when he turned "Billie Jean" into a commercial for Pepsi. Singing about choice, performing in a dead live show: "a stiff, impersonal, over-rehearsed supper club act blown up with lasers and sonic booms....[And how many entertainment 'spectaculars' of the last twenty years does that sum up?] Michael Jackson, who began this year as a dancer, turned into a piece of wood." (Marcus) But what if he had stayed a dancer? What if his moves could have been extricated from that supper-club spectacle? What if the young black man in those Off The Wall videos had not disappeared?

June 26, 2009

The freak of consensual sentimentality

- Greil Marcus: Jackson-ism produced the image of a pop explosion, an event in which pop music crosses political, economic, geographic and racial barriers; in which a new world is suggested. Michael Jackson occupied the center of American cultural life: no other black artist had ever come close.

But a pop explosion not only links those otherwise separated by class, place, color and money; it also divides. Confronted with performers as appealing and disturbing as Elvis Presley, the Beatles or the Sex Pistols -- people who raise the possibility of living in a new way -- some respond and some don't. It became clear that Michael Jackson's explosion was of a new kind.

It was the first pop explosion not to be judged by the subjective quality of the response it provoked, but to be measured by the number of objective commercial exchanges it elicited. Michael Jackson was absolutely correct when he announced, at the height of his year [1984], that his greatest achievement was a Guinness Book of World Records award certifying that Thriller had generated more top-ten singles (seven) than any other LP -- and not, as might have been expected ... "to have proven that music is a universal language," or even "to have demonstrated that with God's help your dreams can come true."

The pop explosions of Elvis, the Beatles and the Sex Pistols had assaulted or subverted social values; Thriller crossed over them like kudzu. The Jackson-ist pop explosion ... was brought forth as a version of the official social reality, generated from Washington D.C. as ideology, and from Madison Avenue as language ... a glamorization of the new American fact that if you weren't on top, you didn't exist.

"Winning," read a Nestle ad featuring an Olympic-style medal cast in chocolate, "is everything." "We have one and only one ambition," said Lee Iacocca for Chrysler. "To be the best. What else is there?" Thus the Victory tour -- which originally boasted a more apocalyptic title: "Final Victory."

- Ian Penman:

... a figure as sick as any America has ever produced or procured as an icon. Jackson is more Howard Hughes than Mickey Mouse, more late-Elvis than ET, and more symbolic of everything despoiled and uncertain about childhood in our century, than the harmless Spielbergian dummy he has for so long (been) painted. In a world that can no longer shock us (Madonna, Damage, Basic Instinct: why should adult stuff shock us?) squeaky-clean Michael has come to represent the creepy, shadow's-spawn side of US celebrity.

... Michael's young audience (whose street gestures, styles and music he ceaselessly recycles – sometimes literally rips off) is happy to accept cartoon imitations of human form and aspiration: he doesn't dress well, his dancing is longer exceptional, his sexual projection is embarrassing – you're embarrassed FOR him. In one video last year, you see him being sideline-coached on how to act like a turned-on adult, and any boy (even – or especially – a Gay one) who doesn't know how to react to Naomi Campbell is way off orbit. Michael has no real glamour or allure: words like Dangerous and Bad roll on/off him without any real pleasure-zing of recognition.

What's falling apart isn't just Michael's face but the face of what it represents: his corporate-Pop dream of eternally renewable identity as the ultimate commodity. (In the '80s, it also appealed to all the new teeny bopper post moderns. Lofty-thinking chaps praised Jackson as the ultimate pop paradigm – he was, with Madonna, the ultimate thesis-fix.)

....America used to dominate us like a Lee Marvin sadist: it had no need of running interference from the emotions. Now it's gotten this "Don't you see I have to, because it was done to me" rap, and wants our wounded puppy tears. It wants pity, not awe. It used to be that you kept it zipped: now we have a "feminised" space of confession. It used to be that America's crucified heroes stalked Death Valleys and New Frontiers. Now they work in electronic space, blip time, sealed inside the soundbite, the video and the Vanity Fair cover.

June 21, 2009

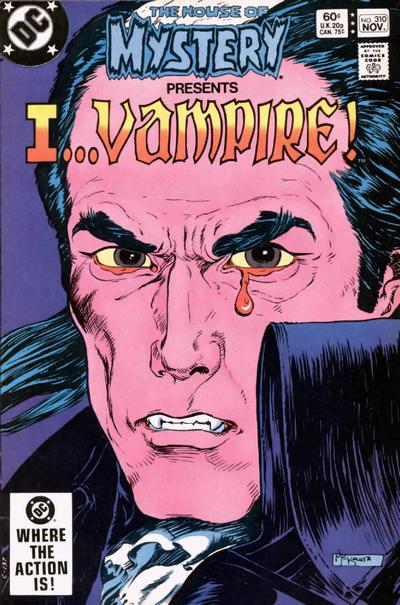

Mommy, what's a grey vampire?

Graham highlights an ambiguity in the concept of the Grey Vampire that occurred to me, but which I hadn't properly resolved: namely, is the Grey Vampire a category of person, or is it a subjective position that anyone can fall into? I would say both. It's certainly true, as Graham says, "that all or many of us might have our vampirish sides. There might be areas of life in which each of us is some sort of bloodsucker." Absolutely, and of course there's nothing wrong with leeching off others' energy and resources if they have an abundance. But what differentiates the Greys from other kinds of vampires is the disavowed nature of the feeding. Grey Vampires don't feed on energy directly, they feed on obstructing projects. The problem is that, often, they don't know that they are doing this. (That's one difference between them and a troll - trolls usually aren't under any illusions about themselves, they just find spurious justifications for their activities.)

There is very definitely a type of person who is a Grey Vampire - I've encountered a few, and, once their shield of sociability and charm falls away, they become revealed as horribly, tragically cursed, existentially blighted. But the Grey Vampire is also a subject position that (any)one can be lured into if you enter certain structures. Part of the reason I can't hack it as an academic is that, in a university environment, I invariably find myself pincered between the troll and Grey Vampire positions. That's why I sincerely admire anyone who can pursue a project in the academy. Although being pressure-cooked in the post-Fordist precarity of freelancing is in some respects extremely difficult (not least in brute economic terms: in an average week, I'm lucky if I make the equivalent of minimum wage; not that I'm complaining - I never forget that I'm extremely fortunate to be able to write, think and teach for a [near] living), in other ways it is very easy. There's a certain lightness and velocity that can be achieved when you are at the edge of employment structures, or passing between them, rather than being embedded in them.

June 20, 2009

June 18, 2009

Some clarifications

Graham makes some important clarifications on the concept of the troll. As Graham rightly points out, trolling does not require anonymity (I would further add that anonymity has nothing to do with facelessness, but that's for another time). Many online trolls use their own names, and in any case, any tag, even if it is only ever used in cyberspace, starts to function as a name if it is used consistently. What's different about the academic environment to the web is not so much that people are named per se. It it that, because of their public profile, academics, as Graham says, are "awash in all kinds of sincerities… we may know a bit about their biases, their hero authors, their musical taste, their personal life, their vices, and so forth." It is these sincerities that compromises their trolling, plus the fact that - if they are actual academics rather than perpetual postgrads - they will be associated with some set of refutable claims for which they can be held accountable . But the continuing influence of poststructuralism (a kind of negative theology of prevaricating academic practice) plus research measurement exercises have made it easier - even mandatory - for humanities academics to retreat into nebulous intricacy and/ or databasing of the sort "X (1993) said Y about Z (1968)". (It's ironic that this discussion should have been prompted by a repudiation of Badiou since one of the great attractions of his theory was a forceful refusal of the academo-deconstructive doxa that making determinate claims or having projects, was 'oppressive'. Not as ironic as making appeals to suffering humanity in a defence of Badiou, but still...)

Without a project, anyone - academic or otherwise - is in danger of falling prey to the lure of the Troll or Grey Vampire subjectivities. Detached from projects, academic skills become pathologies. The only aim becomes to demonstrate how much you have read (never enough - the debt is always infinite) or how much you have thought (always far more than anyone who makes a determinate claim, whom both Trolls and GVs regard as too hasty, too crassly populist, too intemperate, whatever...). It oughtn't be necessary to point out that not everyone who works in an academic institution is an academic qua academic. Many struggle against the structural tendencies, try to hold open higher educational spaces so that they can be something more than an exercise in pointless critique and bureaucratic footnote-policing. The same is true of others facing different structural constraints (such as those imposed by print media). At the moment, it is the discourse networks of the web which provides a unique space, an outside of both the critical compression in the academy and media. It's no accident, for example, that speculative realism is really proliferating and multiplying in an exciting way on the web.

A reader writes, worrying that they might be a Grey Vampire:

- My initial (perhaps defensive!) thought was that the grey vampires potentially offer support, encouragement, and good cheer to those on the frontlines and/or constitute a potential "standing reserve" waiting (maybe that's the problem!) to be mobilized. My current sense is that the greatest or first danger they pose is to themselves and by extension the social or the polity by way of a kind of autoimmune response in which they disable/disarm/disavow/destroy what is most vital in themselves and "deprive" the world of that energy/quality.

The debilitating effects of the Grey Vampire are often much harder to identify and combat. They are 'friendly', they seem to be positive, they make their points respectfully - what's to dislike? Ultimately, though, their stance is precisely the same as the Troll - they are profoundly suspicious of commitments and projects, except that their anti-productivity comes out as sunny scepticism instead of outright aggression. One of their favourite tactics is the devil's advocate appeal to what someone else, not them, might think. Might not things be seen in another way? (This would be completely different if they were making a point that they were prepared to subjectively identify with: then we could get somewhere, then there would be an actual difference of positions, instead of one position confronting an infinite series of movable obstacles and promissory notes.) Another tactic - particularly effective at wasting time and energy this one - is the claim that all they want is a few clarifications, as if they are just on the brink of being persuaded, when in fact the real aim is to lure you into the swamp of sceptical inertia and mild depression in which they languish.

Grey Vampires are not a standing reserve because - this is the awful tragedy, the terrible revelation that eventually strikes you about them - they will never be mobilised. Like the Troll, their alibi - to themselves as much as to others (and to the big Other) - is that they are always about to do something major - their scepticism, equivocation and vacillation is just a temporary phase, soon to be set aside. But the Grey Vampire never has much of a sense of urgency. That's partly because they don't feel that they have to justify themselves to the world (sometimes there is a class dimension here - the GVs tend to have an implacable core of inner confidence which is the birthright of the dominant classes). They worry about their vacillating drift, but not too much. They have doubts, but - sadly in many ways - those doubts will never harden into a breakdown, any kind of subjective destitution.

Another reason that the GVs are so difficult to deal with is that they are very adept at playing to a gallery of 'reasonable' observers - if you respond angrily to them, or cut them off, they will find it much easier to get support than do trolls. After all, they are only asking questions - what could be wrong with that? But occasionally GVs can be caught out. Beneath the moth-grey sadness of the GVs, there is always a raging red core of useless anger and resentment - the worst kind of anger and resentment, because it is directed against those who have projects. This anger is rarely seen, because any expression of intemperance risks undermining the GV's image as friendly and reasonable, upon which their deflationary power crucially depends.

What most worries Grey Vampires is the question of standing - they will tend not to make a claim that might make them ridiculous in the eyes of already-constituted authorities. Of course from outside - and from inside too - it can be difficult to distinguish a Grey Vampire from someone in a state of pre-commitment confusion. One factor, here, as Graham has pointed out, is age - if someone is a procrastinator in their twenties this doesn‘t mean they are permanently trapped, but if they are still vacillating in their late thirties or older, they may well be a GV. Usually, though, the major clue that someone is not a GV is the willngness and capacity to be taken over by a depersonalisng passion. Grey Vampires, like Trolls, tend to be extremely self-conscious, and part of what motivates them is a poisonous envy of others who are possessed by this kind of depersonalising passion.

Fans, of course, do let themselves be taken over by passions of this type. This is why, from the Grey Vampire perspective of jaded postmodernity, fans look gauche and unsophisticated; they lack the proper restraint, they do not have enough humour about themselves. Graham dispels some fallacies about the fan.

- Being a fan doesn’t mean being "uncritical." There is not some sort of opposition between gullible belief on one side and critical distance on the other. The fan stands somewhere in between the devotee and the critic.

In fact, being a fan of someone most often means "cutting them some slack." A true devotee would not need to do this, because the devotee (or "sycophant", if you prefer) never admits that the object of worship did anything wrong in the first place.

Far from being uncritical dupes, fans will often be more critical of their object of adoration than anyone else is; in part, evidently, because they care far more than those who haven't made the libidinal investment. (This doesn't mean that fans won't close ranks when their object is attacked by an outsider.) I say 'object of adoration' but 'adoration' doesn't really capture the fan's relation to the object. The object isn't so much adored as fetishised, elevated into the position of an idol, the figure around and through which libido is organised. But the mistake of anglo-American deflationism is its notion that we can simply dispense with this kind of fetishism and just deal with propositions. Some kind of attitudinal/ libidinal stake is always necessary to get things going; the issue is whether it is foregrounded and affirmed or occulted and denied. Passing beyond being a fan is not achieved by occupying a chimeric position of libidinal neutrality, but precisely by following the implications of the libidinal investment.

What's interesting is the point at which a fan's criticism crosses over and becomes a betrayal. Often, though, betrayal is not a consequence of critical dissatisfaction, but of fidelity. Take the example of Graham himself - in some sense he is still a fan of Heidegger; in another sense, not least in his refusal of Heidegger's priestly mystagogic ponderousness, Graham is the greatest betrayer of Heidegger. (Zizek could also be considered a betrayer of Lacan for the same reason: expounding Lacan's doctrines in a lucid style could be seen as depriving them of something essential, their late modernist intractability.) Graham's whole dethroning of Dasein in favour of objects is poorly understood as apostasy. Rather, it is a consequence of Graham's being true to what he sees as the essential core of Heidegger's philosophy, what is in Heidegger more than himself.

Interesting consequences also follow from being a fan of more than one thing at the same time. (cf Graham's being a fan of both Heidegger and Latour.) The Last Man stance is to keep the two objects separate, to insist on their irreducibility to one another. But it's far more interesting to ask the question: is there any principle or set of principles that can allow me to be a fan of both of these two things? Is there some invisible consistency that binds them? Or must I favour one over the other, and on what grounds?

_________________________________________________________________

Levi adds to the bestiary, and here gives a convincing account both of the initial appeal of Badiou and of some of the problems with his ontology. Levi shows how the emergence of a philosopher depends upon a certain kind of enjoyment.

- I suppose you could say that I took an impish pleasure in how Badiou must stick in the craw of my fellow Continentalists. I will never forget having coffee with a very well known Continentalist in his own right, my face, words, and gestures animated by my enthusiasm for Badiou like a child having at it with a new toy, only to hear him despairingly say “it’s kinda like analytic philosophy, though.” Kinda, but not quite. Badiou had really hit a symptom at the heart of contemporary Continental thought. Where Derrida and the others were endlessly talking about free play and dissemination, Badiou put his finger on the remarkable univocity of mathematical prescription. But this is not all. Where everyone was endlessly talking about difference, Badiou took this one step further, developing a radical articulation of difference. Many of us had become accustomed, through Heidegger, to thinking of maths as the most extreme form of enframing and identity thinking. What Badiou showed, through his deployment of set theory, was that far from the valorization of identity, maths give us the resources to think multiplicities qua multiplicities without one, or absolute difference and dissemination. Similarly, where many were celebrating the accomplishment of Derrida’s thought and the aporetic undecidables it acquaints us with in every domain, Badiou dared to declare that we must decide the undecidable, and articulated a rigorous account for doing so through his discussions of forcing and the generic with respect to truth-procedures. Indeed, the very fact that he said truth at all, and in such an interesting way, was a shock to the system within that intellectual context.

It's worth remembering here, though, how Badiou shares continentalism's contempt for science - the 'science' that Badiou writes of positively is of course nothing other than mathematics - but in his case, the disdain is motivated by opposite reasons. Whereas Heidegger and his supporters recoiled in horror from science's 'totalitarian descralization' of Being, Badiou rejects empirical science because it is too fuzzily mired in the material world.

_________________________________________________________________

For those who haven't seen them yet: these three crucial posts by Dominic are invaluable ... For me, militant dysphoria is not something that is already there, it's something that has to be constructed. The question is how to convert the vast black reservoir of youth disaffection into militancy without subordinating the maladjustment to some social-reality-pleasure principle, without, that is to say, sublating its negativity into some higher positivity. Perhaps it isn't a question of conversion at all, but of drawing from the well of negativity. As Dominic says, dysphoria isn't a lifestyle - it would be better to see it as an anti-lifestyle, in the double sense that it rejects not the very concept of lifestyle but also sets itself against the imperatives of life, the idiotic positivity built into the vital. Marxism must be anti-social or not at all. And I really will return to this in the eliminativist Marxism post.

June 13, 2009

Vital signs: negative

[Ultra-compressed notes on T4]

If you're reading this, you are the resistance.

And right on cue: Terminator: Salvation delivers the scorched earth mythscape for our year zero. Earth as ground zero, an ultramilitarized zone in the grip of an ongoing catastrophe. Everything in ruins: a fictional diagram of Now. CGI finally codes for CyberGothic, the battered future returning as an infernal landscape bolted together out of Black Metal nightmares, Apocaplyse Now choppers, towering War Of The Worlds-like megacidal machines and videogame ballistics.

Accelerationism as thrill-ride, deep-cooled in cold libido, which the final few minutes of sentimentalism can't recuperate for humanist overcode.

Narrative compressed into speed blips. Dialogue as junglistic soundbites.

'What just happened?' 'Judgement Day'.

It really believes it's human. (Like you do.)

You are a good man. (Echoes of Roy Batty's taunt to Deckard: 'aren't you the good man.')

Cyborg catatonia.

Symbolic exchange and machinic death.

The difference between us and the machines is that we bury our dead.

There is no fate

June 12, 2009

Fans, vampires, trolls, Masters

One of the many fascinating things about Alex's properly punk provocation is the immuno-response it has induced (and, ladies and gentlemen, if punk means anything it is this kind of divisive unsettling of good sense; choose your sides - and it's not a matter of agreeing with the content, it's whether you can cope with the intemperance and the impatience of the style, whether, in the end, when faced with this kind of thing, you will take refuge from the scouring challenges of theoretical abstraction in guffawing Guardianista commonsense or scholarly piety).

This must be the work of disappointed fans, we are told. The implication here is double: the vicissitudes of fan-adoration have no relationship to proper philosophical discussion, and fan exasperation, the nihilation of the former idol, is somehow juvenile.

It's always other people who are 'fans': our own attachments, we like to pretend (to ourselves; others are unlikely to be convinced) have been arrived at by a properly judicious process and are not at all excessive. There's a peculiar shame involved in admitting that one is a fan, perhaps because it involves being caught out in a fantasy-identification. 'Maturity' insists that we remember with hostile distaste, gentle embarrassment or sympathetic condescenscion when we were first swept up by something - when, in the first flushes of devotion, we tried to copy the style, the tone; when, that is, we are drawn into the impossible quest of trying to become what the Other is it to us. This is the only kind of 'love' that has real philosophical implications, the passion capable of shaking us out of sensus communis. Smirking postmodernity images the fan as the sad geekish Trekkie, pathetically, fetishistically invested in what - all good sense knows - is embarrassing trivia. But this lofty, purportedly olympian perspective is nothing but the view of the Last Man. Which isn't to make the fatuous relativist claim that devotees of Badiou are the same as Trekkies; it is to make the point that Graham has been tirelessly reiterating - that the critique from nowhere is nothing but trolling. Trolls pride themselves on not being fans, on not having the investments shared by those occupying whatever space they are trolling. Trolls are not limited to cyberspace, although, evidently, zones of cyberspace - comments boxes and discussion boards - are particularly congenial for them. And of course the elementary Troll gesture is the disavowal of cyberspace itself. In a typical gesture of flailing impotence that nevertheless has effects - of energy-drain and demoralisation - the Troll spends a great deal of time on the web saying how debased, how unsophisticated, the web is - by contrast, we have to conclude, with the superb work routinely being turned out by 'professionals' in the media and the academy.

In many ways, the academic qua academic is the Troll par excellence. Postgraduate study has a propensity to breeds trolls; in the worst cases, the mode of nitpicking critique (and autocritique) required by academic training turns people into permanent trolls, trolls who troll themselves, who transform their inability to commit to any position into a virtue, a sign of their maturity (opposed, in their minds, to the allegedly infantile attachments of The Fan). But there is nothing more adolescent - in the worst way - than this posture of alleged detachment, this sneer from nowhere. For what it disavows is its own investments; an investment in always being at the edge of projects it can neither commit to nor entirely sever itself from - the worst kind of libidinal configuration, an appalling trap, an existential toxicity which ensures debilitation for all who come into contact with it (if only that in terms of time and energy wasted - the Troll above all wants to waste time, its libido involves a banal sadism, the dull malice of snatching people's toys away from them).

Related to Trolls, and in some ways even more dangerous, are what Scanshifts and I call Grey Vampires: Grey Vampires are creatures who disguise their moth-greyness in iridescent brightness, all the colours of attractive sociability. Like moths, they are drawn by the light of energetic commitment, but unable to themselves commit. Unlike the Toll, the Grey Vampire's mode is not aggressive, at least not actively so; the Grey Vampire is a moth-like only on the inside. On the outside, they are bright, humorous, positive - everyone likes them. But they are possessed by a a deep, implacable sadness. They feed on the energy of those who are devoted, but they cannot devote themselves to anything.

The dominant modes of subjectivity at the end of history/ web 2.0 are those of the Troll and the Grey Vampire, the two faces of the Last Man. This isn't to say that most people are not fans; they are, but many work hard to conceal this about themselves, for it makes them vulnerable to attacks from Trolls or Grey Vampires, or the Trolls or Grey Vampires in themselves. They are subordinated to The Fear and its demand that we be irreverent, that we constitute ourselves as ironically self-deflating subjects (I'm the sort of person who....). The postmodern academic, complicit with the system that immiserates them, reflexively impotent, is required to oscilate between being Troll and Grey Vampire, between hyper-critical scholarliness and convivial sociality, kept locked into the system by just the right level of prestige and self-loathing. That's why most of the interesting work done in institutions is achieved by people who have infiltrated the academy after periods of (intellectual and subjective) destitution.

So I will admit it: I am a fan, and this holds for my philosophical, as much as my cultural, investments. The two are in any case interchangeable - there is a philosophy implicit in any cultural product worth its salt (as Dominic, Alex and Reza demonstrate with their method-analyses of Black Metal, whose fanaticism make it the black mirror reverse of the overground kingdom of Trolls and Grey Vampires. And the anti-social dysphoria of Black Metal - being no-one - has far more to offer any 21st century Marxism than the moralising homilies of clubbable, pubbish socialism.)

There is a strong relationship between the Fan and the critic. The best critics do not pretend to offer value-neutal judgements from nowhere - as Nietzsche, Marx, Freud and Lacan have shown in their different ways, no such place exists , although the fantasy position of something like Analytic Philosophy is to pretend that it does. Again, this is not a relativist or anti-realist point - any sophisticated realist position has to deal with the fact that we can't step over own own shadow (but, as Graham and Levi insist, rightly in my view, a commitment to realism does not entail any human access to the real; in fact, it is more likely to mean the opposite).

Even at its most debased, there is a systematicity to Fan devotion, and it is this systematicity which the good sense of Web 2.0 'irreverence' always recoils from and mocks. Imagine believing something, it's so vulgar, tasteless, embarrassing... This 'systematicity' looks 'silly' considered from the armchair of the Last Man - but so is any reality system - including that of anglo saxon nominalism - viewed from outside (isn't this one of the abiding lessons of Foucault, the point of his famous invocation of Borges's taxonomy at the start of The Order Of Things?) And of course there is no more 'silly' system than Badiou's, an ultra-intricate chain of entailments and exclusions which only the super-dedicated professional or the monastic devotee can have the time and energy to explore. But the new and the sublime is just as likely to initially seem 'silly' as it is incomprehensible or distressing (cf Jungle, which was snootily dismissed as 'silly' by IDMers.)

Really, the 'Badiou backlash' started with Ray's memorable exasperation at the Middlesex Being And Event non-event, when, at the end, he asked if Badiou's system is anything more than a elaborate folly. It was a bracing intervention after a day of soporific solemnity. If the vice of Deleuzianism was the encouragement it gave horrible slew of New Age vitalisms, nu-language anti-thinking artspeak (no need to be coherent, just be creative) and happy-clappy pro-capitalist positivity, one of the most regrettable effects of Badiou's pre-eminece has been to restore the prestige of philosophical priest-scholar po-facedness - I take Levi's point that much of the appeal of Zizek for certain Cult Studs types is that he legitimates talking about TV programmes and films, but the appeal of Badiou for another kind of academic is that they don't have to discuss television or media, and can reassure themselves that talking about bourgeois kitsch in art galleries, museums and university departments is the proper pursuit of the Philosopher; that's why the Paul Bowman critique had a certain point.

There's a certain disingenuousness in Badiou-devotees complaining of slaying the Master, when, in the UK world at least, so much of the impetus behind the move to Badiou came from disappointed and/ or defecting Deleuzians. As one of Graham's correspondents rightly observes, it is hard to see Badiou - both in terms of the sociology of his reception and the status of his philosophical project - except as the anti-Deleuze. Anti-Deleuzianism was certainly necessary in this dismal decade; and Badiou played a part in waking me from my Deleuzian slumber, but - and here's a confession no proper philosopher should make - Zizek played more of a part. I've been a Zizek fan, but I only ever admired (aspects of) Badiou.

Betrayal is just as important a cultural engine as fidelity; hate is just as important as love. But only the fan can betray, only the lover can hate. That's why betrayal and hate are as alien to the Troll as they are to the Grey Vampires.

The problem with Badiou and Zizek is not any totalitarianism, but the fact that their politics are postmodern simulations played out for an academic gallery: 'comedy Maoism' and 'comedy Stalinism', as Alex has put it. Their immense value this decade was to de-naturalise capitalist realism, and to expose the complicity of pomo sophistry and deconstructive indecision in the neoliberal reality picture, but both remain victims of the Old Left vice of looking backwards. This is far more true of Badiou than of Zizek, who will engage with neurophilosophy and genetic engineering. One of the strange things about Badiou is the curious retrospective temporality of his literally post-modernist philosophy - this is what it was to be a militant, this is what it was to fall in love... well, yes, but, now what? What's rousing about The Meaning Of Sarkozy is precisely the call to start again from nothing. We need to take him at his word here. Badiou has led us through the desert of the hyperreal, but the promised land turns out to be a scorched earth where the raddled old communist ideas, terms and histories cannot take root. Time for the last of the 68 fathers to be ushered offstage. Time for speculative realism to come to the centre. And I'll return to this in the long-promised eliminativist Marxist post.

Behind the curtain

Some of you might have seen fragments of an unfinished post here, which I posted up by accident (a brief glimpse behind the curtain into the k-punk lab of half-formed posts)... That post is part of the long-promised extended response to the Idea Of Communism conference, now given a new urgency by Alex's glorious act of nihilation. I will complete that post and post it up properly in the next day or so; in the meantime I'm working on another post on Fans, Trolls and Masters which should be up later on today.

June 10, 2009

I must fight this sickness

Dominic articulates some of the objections I too have with Alex's valuably provocative post. Alex has brilliantlly mobilised and mutated some of Reza's decay-thought (not least in his bravura theorization of Wonky, fully vindicated by the new Sa-Ra Creative Partners record, for me one of the albums of the decade, and fitting Alex's deliquescent-description perfectly - see my review in the latest issue of The Wire). But I'm not sure if there isn't a confusion of registers here - the corruption to which I (and I think Dominic) are referring is not some grand liquefaction, some rot teeming with pestilential potential. It's more tawdry, dreary and deadening than that. The current disintegration of capitalist parliamentarianism is yielding no fructifying putrescence, only a cynical confirmation of the capitalist realist sense that everything is both base - and boring. The corruption I'm talking about is the corruption of PR, capital's natural language, and something which has indeed insidiously infects all aspects of work and culture, but not in any way that is interesting.

What I find most valuable in Badiou is precisely the emphasis on anti-worldliness; but 'being worldly' is of course not the same as 'being material'. 'Worldliness' entails accommodating oneself to a social phenomenology (to use a phrase Ben recently invoked), a set of determinations about what is possible which, crucially, have nothing to do with the constraints imposed by materiality. What's inspiring about Badiou's polemics is, in other words, their refusal of capitalist realism (which in one of its guises is the Sarkozyism magnificently eviscerated in The Meaning Of Sarkozy.) And what appeals to me about Badiou is certainly not The System (which as a maths-incompetent I have little affinity for and limited interest in) but his delineation of a militant phenomenology, his demand that we maintain fidelity with that mode of subjectivity which, through struggle, through unplugging from the dull somnambulism of the social, has attained a higher pitch of existence. The problem for me is that this seems to amount to a descriptive itinerary which might be encouraging but has limiited political application - the political question is how these militant break-outs can be engineered, not what they are like once they have already happened. (I think Alex is right that speculative realism might offer better resources for thinking a new politics than Badiou's retro-modernism.)

Yet none of this has anything to do with the year zero I've been talking about. Year zero will not confer militant subjectivity on anyone as of right; nor will it redemptively 'cleanse' us. Year zero very definitely does mean a 'clean slate'. It means a cleared space. It is not a pristine space; far from it, as Alex himself memorably put it, it's a space strewn with 'ideological rubble'. The 'neoliberal reboot' that Dominic fears is one way - the dreariest - that the space could be used. Yet it isn't the only way. The neoliberal mind paralysis is over, even if we are only just, fitfully, reviving from its pacifying effects. To take advantage of the ideological dereliction that we're in the midst of entails not ascending into some sanitised high ground but - quite to the contrary - dirtying our hands with the problem of organisation. We must also dirty our hands by fighting over the popular terrains - media, cyberspace - that Badiou, at his high-handed worst, is wont to a priori dismiss.

June 08, 2009

Now the Party's over

|  |

- "It was like being on a liner in mid-ocean when all the engines have stopped. Just drifting silently. The civil service just backs off. If they thought Gordon Brown was going to lose power imminently, that would happen again." - James Callaghan's senior policy adviser, Bernard Donoughue, talking to Andy Beckett in 2008 about the Whitehall response to Callaghan's impending defeat.

- "For too long, perhps ever since the war, we [have] postponed facing up to fundamental choices and fundamental changes in our economy.... We've been living on borrowed time... The cosy world we were told would go on for ever, where full employment could be guaranteed by a stroke of the chancellor's pen - that cosy world is gone..." - James Callaghan at the 1976 Labour Party conference at Blackpool

What we're seeing now is perhaps the end of a sequence that began, not in 1979, but in 1976. As Andy Beckett points out in his enthralling and expansive study of the 70s, When The Lights Went Out, it was in 1976, that Callaghan - under pressure from the neoliberal IMF - first introduced the Labour Party to capitalist realism with that notorious Blackpool speech. "At the time, "I called the change of attitude the New Realism," Peter Jay, the main architect of Callaghan's fateful speech told Beckett. "Later, Thatcher used that phrase quite a lot." What would have happened if Callaghan's Labour had managed to capitalise on capitalist realism a little more effectively? That is one of the many 'what ifs' which haunt Beckett's book, many of whose chapters read like treatments for David Peace novels. There were many pivotal moments: the bitter Grunwick dispute as pre-echo of the Miners' Strike (with strikebreakers co-ordinating a defeat of the postal blockade, prompting one aghast witness to note, "It made us all realize at the time that when the working man was striking, how much was engineered against him"); the vote of confidence in Callaghan's government, lost by only one, leading to the historic election of 79, which was actually far closer than the myths of the near-past would have us believe.

Or perhaps the sequence which we're seeing limp towards its grim terminus goes back even further, to the beginnings of the twentieth century, and the formation of the Labour Party itself. New Labour's years in power have done more than superficially change the party's image, they have returned us to the conditions of the late nineteenth century when the working class had no representation in parliament at all. At this point, and for a number of resons, it's worth reminding ourselves of Badiou's argument that the left's subsumption into capitalist parliamentarianism cannot be understood using the category of individual moral 'corruption':

- None of the parties which have engaged in engaged in the parliamentary system and won governing power has escaped what I would like to call the subjective law of 'democracy', which is, when all is said and done, what Marx called an 'authorized representative' of capital. And I think that this is because, in order to participate in electoral or governmental representation, you have to conform to the subjectivity it demands - that is, a principle of continuity, of the politique unique - the principle of 'this is the way it is, there is nothing to be done', the principle of Maastricht, of a Europe in conformith with the financial markets, and so on. In France, we've known this for a long time, for again and again, when left-wing parties come to power, they bring with them the themes of disappointment, broken promises, and so forth. I think we need to see this as an inflexible law, not as a matter of corruption. I don't think it happens because people change their minds, but because parliamentary subjectivity compels it. (Interview in the Appendix of Ethics - emphasis added)

What is habitually underestimated - and this might be the defining illusion of all entryists, all would-be reformers who believe that they can change management from within - is the power of structure to generate subjectivity. If Callaghan could invariably, even in the most stressful moments of his immensely stressful premiership, come across as 'Sunny Jim', it was because he was never under many illusions. He was built for (and from) compromise. He accepted disappointment from the start - rather like the Freud who thought the point of psychoanalysis was to deliver patients from excruciating mental agony to 'ordinary misery', Callaghan believed that in politics there were only bad and worse decisions. Yet what counted as 'realism' for Callaghan was partly conditioned by forces outside the parliamentary machine and the financial system - so too, for Thatcher in her first term, when she backed down to the unions. Now, outside parliament anf finance, there is a discontent without focus or organisation: not necessarily a bad thing, if, as I believe it will, it leads to new forms of organisation. But in the meantime, the Nazis will profit, not - thank goodness for small mercies - by increasing their vote but by holding onto it while the Labour vote disintegrates. Grotesquely, the Nazis can present themselves as the actual alternative to an end-of-history consensus which has eliminated all alterity; and every howl of abhorrence from inside the media-parliamentary machine risks further feeding their outsider allure.

In the New Statesman two years ago, Martin Bright summoned Callaghan's spectre. "The ghost of Callaghan hovers over Gordon Brown and those around him," Bright wrote; the parallel then was between Callaghan's failure to call an election in 1978, at a time when the goverment was recovering after the sterling crisis and the IMF debacle and before the Winter Of Discontent, and Brown's similar dithering when he took office. Brown will surely always be haunted by that failure to call an election in the very brief window of time when he might have won one - but all such conjectures belong to another world, another era. We're in a different time now, but one without any heralds - there is no equivalent of Thatcher ready to lay claim to these new times. "There's a world-wide revolt against big government," excessive taxation," said Thatcher on May 1, 1979. "An era is drawing to a close.. At first... people said, 'Oh, you've moved from the centre.' But then opinion began to move too, as the heresies of one period became, as they always do, the orthodoxies of the next... It's said that there is one thing stronger than armies, and that is an idea whose time has come." But our time awaits its idea.

It seems as if we are tumbling and stumbling back towards a version of Callaghan's era, living through a negative 1979... tumbling and stumbling out through a political-economic event horizon that marks the end of neoliberalism (which now fits Nick Land's desription of cybergothic postmodern power: "it's dead, but it carries on") ... with national bankruptcy looming, as it did in 76... and chaos and the Right looming as they were then.... but this time unopposed by any organised labour or a credible hard left ... And the grandfatherly Callaghan, chirpy and self-possessed, rarely depressed, even amidst the Winter of Discontent that would bring him down, could not strike a greater contrast with the morose Brown, a resentful Richard who carries a wintry discontent with him always, on his heavy brows. For Callaghan stood only at what he thought would be a moment of painful transition for the Labour party, whereas Brown looks like the mortfied personification of the final death of the labour movement itself.

I feel satisfied that my analysis of Brown a year ago has been vindicated. For a very brief time, in the immediate moment of sick shock when it became clear that the Blair Boom was definitively over, never to return, it seemed that Brown might, for once, have been the right man for these wrong times. His glower and gravity allowed him to be media-anointed for his preferred role of global statesman, "a serious man for serious times". The glower was real enough, but the gravity, like so much about Brown, was only a simulation, and an unconvincing one, an effect not of moral seriousness, but of the ponderous, painful heaviness which is the ineradicable signature of Brown's anti-style, a residue of wrongness which stains his every gesture, his every move, his every smile. Now Brown must know that he will never be free of Tony's joker hysterical face; Blair's timing turned out to be immaculate, holding onto power for what it is now clear was just the right amount of time, leaving Gordon with the most poisoned of chalices... the cup of bad cheer for the dwarf at the end of history... with Tony laughing and smiling forever...

As for the Nazis, Sarah Ditum is completely right: it's not time "that the BNP’s arguments must be addressed", it's time, instead, that we focused on the real roots of the Nazi support, not in some alleged spontaneously-occurring working class racism, but in "[a] popular media which propagates a constant sense of hostility and anxiety towards non-white, non-Christian groups, and a government which derives its idea of consensus from the opinion pages of the press and vomits up the rhetoric of fear and hate." As Sunny Hundal added in The Guardian: "our media tell people every day that their crumbling infrastructure is the fault of those dastardly asylum seekers (rather than lack of investment, which might mean higher taxes). Immigration wouldn't be such a big issue if local councils presented information more quickly about population movements, so resources could be poured in or taken out in response, ensuring local public services didn't suffer." "This," Hundall adds in a moment of massive understatement, "is also a result of the lack of investment in social housing." One of the most despicable tricks that New Labour has pulled is its collusion with the anti-immigration agenda, which has provided a smokescreen for the party's failure to provide local services and council houses. Exploit cheap immigrant labour in order to keep wages down, and play dead while the popular media blame immigrants for 'taking all the council houses' - which I can assure you, many working class people really do believe is the case. Why wouldn't they, since this is the relentless message they are getting from the mainstream media, a message that is rarely if ever emphatically contradicted by a mainstream parliamentary politician? It's a good job that the working class are not the inveterate racists that many of their patronising 'betters' in the middle class believe them to be, or they would have been voting for the Nazis in their millions, not in their hundreds of thousands.

Here we are, in our new zero, reverse 79, and it's not only the extra-parliamentary force of organised labour that is lacking. What is also missing is the pre-political, anti-protest dysphoria that provoked punk and postpunk; or rather, the dysphoria may exist, but it has not yet found forms of articulation that can differentiate it from the cynicism proper to the capitalist parliamentary spectacle. In their empty administrative acquistivism, MPs reflect back to the voters the realism which they claim is imposed upon them by those selfsame voters. "Worldly realism," writes Dominic in Cold World knows nothing of truth; it is wholly absorbed in deliberating between greater and lesser 'evils', which is to say that it moves entirely within corruption, employing corrupt means in the pursuit of corrupt ends. Such are the 'mechanisms of power' with which we are encouraged to acquaint ourselves. The cold world is the world in which these mechanisms are shown to be incapable of upholding a truth, but to operate rather through a kind of generalised power of falsity." Now we have only the "generalised power of falsity" exposed for what it is... but there is no cold world to see it from, only the collapsed kingdom of lies, in ruin and dereliction, with scowling Gordon at the battered battlements, and the Nazis warming their hands inside the citadel...

June 06, 2009

The Spy who never came in from the cold world

|  |

- And there are some of us, aren't there, who are ... nothing, who are so labile that we astound ourselves. We're the chameleons. I read a story once about a poet who bathed himself in cold fountains so that he could tell he actually existed from the pain of it. [...] People like that, they can't feel anything inside them: no pleasure or pain, no love or hate. They're ashamed and frightened that they can't feel, and their shame, this shame, [....] drives them to extravagance and colour. They have to feel that cold water. Without it, they're nothing. The world sees them as showmen, fantastists, liars, as sensualists perhaps, not for what they are: the living dead.

Listening to Radio 4's adaptation of le Carré's curious A Murder Of Quality (part of the station's dramatiase all of the George Smiley books, and one of the Smiley books I hadn't previously read), I was struck by how much that Smiley belongs in Dominc Fox's Cold World. Set in a public school, A Murder Of Quality sees le Carré (re)turning to the setting and structure of an Agatha Christie whodunnit. The teaming of the erudite Smiley with his local bobby sidekick could be a dry run for the partnership of the posturing Morse and the dull-but-loyal Lewis, although even in a novel as unsure of itself as A Murder Of Quality is, Smiley has a casual depth, a grandeur of subdued sadness and quiet intelligence, which Dexter, for all his puffing and panting, could never imbue the windbag snob Morse with.

I say that Smiley belongs in the Cold World, but that isn't quite right. Smiley, rather, is always drawn back into the Cold World; it's the place of work which he ostensibly abjures, which he officially wants to be free from, but where he actually spends most of his life. It's there he confronts his enemies and near-doppelgangers, those who "are nothing", and who therefore dwell forever in the half-life of the Cold World: later, this will be Bill Haydon and Karla, but in A Murder Of Quality it is the compromised master Fielding. Smiley: always retiring, always drawn back into the permafrost from his lifeworld - which in any case is cold enough, with the very visible absence of Lady Ann, ("Ann isn't living here at the moment"), the Guinevere to his always-ailing Arthur, the constant cuckold's-horn sign of his lack. For Smiley, evidently, the Cold World is usually the no-man's land of the Cold War (le Carré will return to the Cold War in his next novel, the one that will prove to be his breakthrough, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold), and the disappearance of the Cold War background is one of the "oddnesses" - a word that is repeated in the novel - of A Murder Of Quality. The school, as you'd expect of such claustrophobic cloisters, is actually a rather overheated place, with le Carré offering a bitter take on the late-Fifties class condescencions and resentments. Yet amidst all this passion and anger there is the cold discontent of Fielding, and it is in his outbursts (against the futility of reproducing the mediocrity of the ruling class, for instance) that the Radio 4 play achieved its moments of greatest vividness, existential maladptation darkly flaring against the creaking whodunnit scenery. Dysphoria, I'm inclined to think, is le Carré's real subject. Note the slide, in the quotation above, from first-person identification - "there are some of us"- to third-person disavowal - "they are ashamed and frightened that they can't feel". Unlike Fielding, Smiley is no dysphoric by (un)natural inclination, but dysphoria is an occupational hazard to which he - so labile, so chameon-like, so at home in the zone where no-one warm and full can be at home - is far from immune.

June 05, 2009

Being taken over by the fear

|  |

Two tremendous posts by ZoneStyxTravelcard and the resurgent Impostume, which demand some sort of response.

First off, Zone: he is absolutely right that the dominant emotion in mainstream media, cramped by shrinking word-counts, harrassed by demographics, worried that attention might wander, is fear. It's fear - unspoken but ubiquitous - that enforces the cheery-cynical tone that has been so much a part of the background muzak of the nu-50s. And Zone is right about the Lily Allen single, which sounds like everything St Etienne sought to achieve, but never quite managed. Fear was practically palpable in/ behind Allen's television series, which - with its YouTube tie-ins, its wooden flailings at 'interactivity' - summed up everything wretched about this decade's culture: the drab hedonic conservatism, the perpetually perky unpopular populism, so desperate to be liked by everyone that it appeals to no-one. "The Fear" gives voice to the ineradicable but disavowed existential anxiety that hangs like a pall of forbidden cigarette smoke behind all the dead parties and PR pseudo-events of 00s CeleBritain, still listlessly persisting even though the Weimar/ boom background has fallen away. In its own way "The Fear" is as bleak as "Smells Like Teen Spirit". "Bubbelgum nihilism" was the phrase Simon used of Dizzee's "Bonkers", and that captures something of "The Fear"'s poise and despair, but the exisential predicament that "The Fear" articulates is ultimately more reminiscent of the Boy In Da Corner Dizzee. Like much of Boy In Da Corner, "The Fear" is about a youth reflexive impotence that it is itself paralysed by ("I am a weapon of massive consumption/ it's not my fault/ it's how I'm programmed to function"). All Allen can do is point to her own inertia and complicity but awareness can only reinforce the very condition she is talking about - it's Nina's "one-dimensional woman" morosely looking into the mirror ("I'll take off my clothes and it will be shameless/ cos everyone knows that's how you become famous"). The verses are unsure whether they want to be satire or not, unsure whether they want to mock consumer-nihilism or celebrate it , unsure because - after all - what's the alternative, where can all this mocked from? ("It's all about fast cars/ and cussing each other"- capitalist realism satirised and exemplified.) Celebrity culture and its critique are coterminous; the jeremiads about its superficiality as cliched and empty as the culture itself, both appearing on the same pages of LondonLite. Only the negative capability of the choruses, only the admission of The Fear, breaks out of this circuit.

(Just briefly on the SY points: I brought up Swans not to compare their whole career with that of Starbucks Youth, but simply to refute the idea that No Wave was some dead-end, entailing retreat. Swans' records up to 85 emphatically demonstrated that wasn't the case. As for the Starbucks question: the claim that we shouldn't accept the 'individual responsibility' foisted upon us by corporations is surely not equivalent to the claim that we are absolved of responsibility for the way in which we shore up corporations by consuming their products; it's precisely this impasse which "The Fear" examines/ exemplifies, and which we have to think beyond.)

As for Carl's satirical remarks - I refuse to take these as anything other than a compliment, not even backhanded. Really, they are about theory's power, not to generate culture, but to elucidate and intensify it. What's interesting - and this has a direct bearing on some of the disputes about abstraction and the HCC to which I will return in a post that's been germinating ever since the UEL event - is the way in which Burial's music conducted affects and images so powerfully, so lucidly, without the mediation of the (facialised, biographical) individual or its self-understandings. (How different is Burial's abstract art - so painterly, so precise in the images it produced - to so much of what appears in galleries, with its overthought, overconscious, nulanguage meta-rationales, while 'the work' induces no ideas, no affects, at all.)

My first post about Burial was based on nothing more than a CDR, Kode9's press release and obsessive listening, mostly done while walking the South London streets near to where Carl himself lives. Walking and listening, listening and walking, (music and walking, my psychotropics: walking is psychedelic, as we said at the Gasworks londonunderlondon event), not being able to listen to anything else, not being able to settle until I'd written about it. (Contra the boring accusations - not made by Carl needless to say - that I write about music from a dry and dessicated perspective, this kind of method writing is the approach that I generally try to adopt; sometimes, as in the case of Burial, there is no need to try, it was a matter of being possessed, taken over by the music.) As I think I said in that first post, Burial's was a music that I'd dreamt of; or so it seemed: it immediately struck me as something familar. Burial's music certainly felt like it came from the same city as londonunderlondon - and not because of anything so crassly causal as influence, but because they'd both reached a Real of London. Often, the signature of the Real in art is the sense that a landscape, a terrain, has opened up that you feel you can move through - either literally or abstractly, sometimes both. ... And no-one was more surprised than me that Burial liked M R James. I literally could not have made that up, (nor would have done, surely, if I actually was trying to run a scam).