May 29, 2009

How the world got turned the right way up again

(or, FROM POSTPUNK TO RESTORATION)

April 18th 2009

This text was written as an exploration/ exploration of some of the concepts/ inspirations at work/ play in/ behind Michael Wilkinson's show at the Modern Institute in Glasgow, Lions After Slumber. The text includes some materials remixed from this site, but not so many that it is redundant to post it here.

The music is obviously integral to the piece. At Glasgow, I tried to apply some of the lessons I learned from the Gasworks londonunderlondon event. Playing the tracks at high volume and demanding that people listen to them collectively - as if, as someone in Glasgow put it, they were at "a postpunk prayer meeting" - produced a unique atmosphere, both disrupting the standard mode of casual socialising and interrupting for a while the digital twitch of matrix 2.0 and its perpetual attention-drift. I'd never heard "Don't Sell Your Dreams" played so loud; it seemed like a completely different track. Which made me think (again) that rather than the ATP model of having the ageing group play 'classic albums' live onstage, why not gather people together and just play the actual album on a massive soundsystem? The same thing occurred to me watching the Joy Divison documentary: I suddenly realised that I'd never before had the opportunity to hear Joy Divsion's tracks played that loud.

Play DON'T SELL YOUR DREAMS by The Pop Group

PART 1: DON’T SELL YOUR DREAMS

How could a sound like this ever have been made?

A whole secret history of the 20th century is onerically compressed into this lugubrious, delirious sonic anarchitecture

This incandescent condensation of Stockhausen, Duchamp, KingTubby, Albert Ayler, Guy Debord

Amazing that it was work of teenagers - and yet was there ever a sound which channelled the inchoate intensities of a certain kind of teenage overreaching better than this?

A polymorphous punk-funkadelia predeconstructed by dub,

flirting with collapse and chaos,

so close to stasis and ennui,

so gauche,

but in its very gaucherie, in its refusal of embarrassment, a euphoric shattering of the social

in the name of a dream collectivity, a dreaming we, a dreamed we

And not skulking on the margins, but exploding in the heart of the commodity.

On the front of the NME.

1979 - a different world.

What kind of voice is this? You couldn’t call it singing.

It makes you think, instead, of Artaud howling against the straitjaketing of his body without organs at the asylum at Rodez.

It incants, it chants

It speaks in slogans

It makes a demand for the impossible, the only kind of demand worth making.

A demand that is not addressed to the big Other, but which precisely presupposes the destruction of the Symbolic order.

We’ll kill the world

A passion for the real. That old twentieth century dream.

It is an injunction, an interpellation,

addressed to you, just as advertising is.

Don’t sell your dreams

It is addressed to another you, not the placeholder self that you that you often mistake yourself for.

Not that dupe-doppelganger embedded in the social networks, but something else.

Something you see only in shattered mirrors.

Something abandoned, betrayed.

And betrayal is always a matter of forgetting, and then forgetting that you have forgotten.

The perfect crime.

Badiou explains:

“Betrayal is not mere renunciation. Unfortunately, one cannot simply ‘renounce’ a truth. The denial of the Immortal in myself is something quite different from an abandonment, a cessatation: I must convince myself that the Immortal never existed, and thus rally to opinion’s perception of this point - opinion, whose sole purpose, in the service of interests, is precisely this negation.” (E 79)

How, under the tyranny of ceaselessly circulating opinion,

How are we -

We who are not a we -

How are we to hear this now?

How can we

We who can no longer be a we

Who instead identify with the I of interactivity

Who circulate in spaces, which no matter how populous, are always only ever MySpace,

How do we

Whose dreams already come to us trademarked

Whose every desire has been preformatted by capital

How do we respond to this?

With the condescension of good sense, the maturity of proper adjustment?

Alenka Zupancic tries to wake us up.

'The reality principle is not some kind of natural way associated with how things are, to which sublimation would oppose itself in the name of some Idea. The reality principle itself is ideologically mediated; one could even claim that it constitutes the highest form of ideology, the ideology that presents itself as empirical fact (or biological, economic...) necessity (and that we tend to perceive as nonideological). It is precisely here that we should be most alert to the functioning of ideology.'

PART 2: WHICH WAY IS UP?

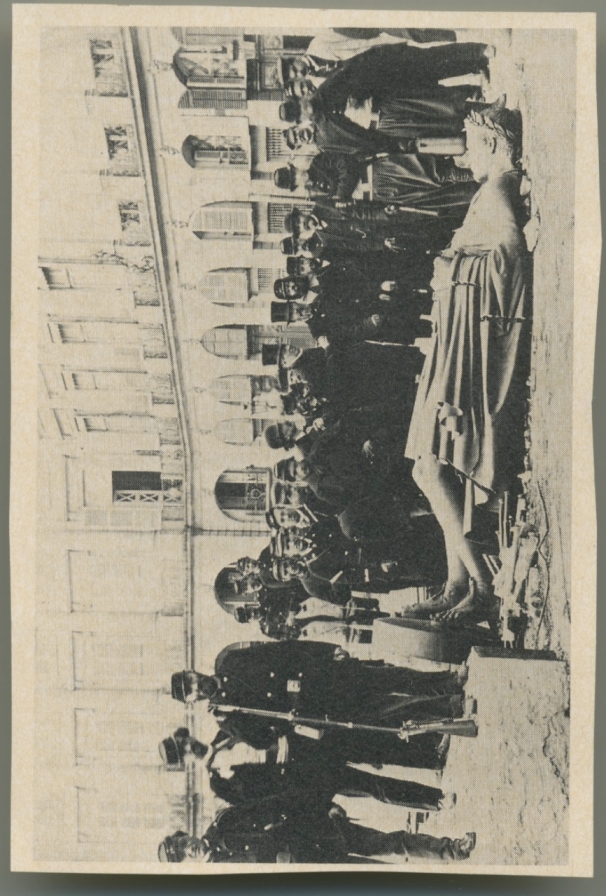

Place Vendôme, Paris. 1871. The Communards pose with the toppled statue of Napoleon.

When Michael Wilkinson turns the image on its side, it looks now as if the statue is upright and the crowd are dead, laid out in coffins.

The world turned the right way up again.

Except that we can now see that there is no right way up.

Antagonism is constitutive of the social.

Either the emperor stands upright , and the people are dead.

Or the people stand upright, and the emperor is dead.

PART 3: TALIBAN ART

- STATE OF MISERY: A special report.; Afghans Ruled by Taliban: Poor, Isolated, but Secure

By BARRY BEARAK

Saturday, October 10, 1998

Music is banned as hedonistic, though tape players are still available, their use intended only for approved recordings. Something that might be called Taliban rap -- prayerful chants without instrumentation -- is deemed acceptable. A typical lyric is: ''Do not kill the flowers of the mosque. Do not kill the words of the Koran. Do not kill the Taliban.''

Music appreciation is not an offence that leads to jail. Contraband cassettes are merely confiscated, the unspooled tape then hung from trees and telephone wires.

Perhaps this is why people continue to take the risk. Hamid Gul, 18, said he plays his Elvis Presley recordings, careful to keep the volume low. Hamayun Ahmed, a driver, replaces his cassette of Pushtun pop with Taliban rap each time he approaches a checkpoint or toll booth.

Of course there is more at stake in the image of hanging, unspooled tape than that - the end of analogue, of a certain regime of materiality.

The tangling of time.

The unspooling of history.

The rejection of aesthetics, albeit in the form of an aesthetic gesture.

But isn’t what is terrifying about the Taliban precisely their rejection of postmodern capital’s compulsory aestheticisation, its triumphal-deflationist reduction of all beliefs to artefacts in the end of history museum? Theirs is the terror of the Real; the terror of a belief that refuses to become culture, that will not reduce into a language game.

In another sense, though, isn’t this modelling of the Real, this version of belief, this account of Terror, already incorporated into the end of history DVD?

Here, the Taliban play a very different role to the one they played in the Cold War movie.

They are Bond villains with very real blood.

Behold the believer, behold the fanatic.

Commit yourself, dare to believe, and you become this.

“Opinion tells me (and therefore I tell myself, for I am never fully outside opinion, that my fidelity may well be terror exerted against myself, and that the fidelity to which I am faithful looks very much like - too much like - this or that certified Evil.”

And then….

And then

You will be bombed back into scepticism.

PART 4: KNOWLEDGE AND INTERESTS

February 2009. The end of history plus twenty years.

Everything is as it should be. All is right with the world. The emperor has been stood back on his feet again for a long time.

Various postpunk types, including Tom Morley of Scritti Politti and Viv Albertine of The Slits, are arranged on stage.

They are here to discuss Simon Reynolds’s book, Totally Wired: Postpunk Interviews And Overviews, the follow-up to his book, Rip It Up And Start Again.

An alternative title that Reynolds considered for Rip It Up And Start Again was Don’t Sell Your Dreams.

Morley retains his dreadlocks, but he now uses his drums in his business of corporate team-building. Albertine is excited by the possibilities of releasing music on MySpace.

They look slightly bewildered, former lions who have slumbered so long that they have forgotten that they were ever awake.

Forgotten what it is to be awake.

They speak blearily, vaguely

Amnesiac talk about the strictures and strictness of those times

Terror and ascesis

Dogmatism and discipline

The supposed autocrats who imposed it

Green Gartside, Mclaren, Westwood

Tough back then

Every aspect of your life, your clothes, your sexuality, under scrutiny

You couldn’t be yourself

Now it’s OK to say that you like Neil Young

Anything goes

Then the music starts,

And everyone wakes up

Play KNOWLEDGE AND INTERESTS by SCRITTI POLITTI

Even in its malformed messiness, even with all its sound-potholes and indecisions, there is an icy lucidity to Scritti‘s music at this time. The time being 1978.

It is a laser cut through the end of history haze.

Unlike The Pop Group, there is nothing Dionysiac about Scritti.

In fact, they were possibly the least Dionysiac pop group ever.

The methodology then was improvisational, but the group didn't want anyone (least of all themselves) to be under the illusion that it issued from some vitalist wellspring of creativity.

It was the sound of a collectivity thinking (itself into existence) under and through material constraints.

Talking to Simon Reynolds five years ago, Green said:

- “It’s a kind of scratching, collapsing, irritated, dissatisfied music. I was listening to some music the other night, on 6 FM or whatever it’s called, BBC 6, their alternative rock station, and I was struck by all the bands: there was no trepidation. I had no sense that the bands were ever playing with anything that they were slightly frightened of - in themselves or in the music. No sense that they were going anywhere where they weren’t sure where they would end up.

Reynolds replied:

- With so much of the music of that period, but especially Scritti, there’s precisely what you’re talking about: a feeling of precariousness. A real sense of anxious struggle, people grappling with these deep doubts and exorbitant hopes: where do we go next after punk?

The question to ask now is: how is this doubt beat, this negative capability, different from blank postmodern scepticism, from the end of history’s circulation of infinitely revisable opinion?

Because it is a matter of questing as much as questioning

Of exploring a new space

A space that is under construction

A space that is a gap in the world

A puncture wound, described by Alenka Zupancic:

“Sublimation is thus related to ethics insofar as it is not entirely subordinated to the reality principle, but liberates or creates a space from which it is possible to attribute certain values to something other than the recognized and established "common good." ... What is at stake is not the act of replacing one "good" (or one value) with the same planetary system of the reality principle. The creative act of sublimation is not only a creation of some new good, but also (and principally) the creation and maintenance of a certain space for objects that have no place in the given, extant reality, objects that are considered "impossible."'

What was the 'beyond good and evil' of Scritti, the Pop Group and the Raincoats if not the production of just such a space?

(As Lacan wryly notes, when we idly think of someone who is 'beyond good and evil' we are liable to think of someone is merely beyond 'good'.)

What on the one hand is an austere asceticism is at the same time engineering of new forms of enjoyment.

In flight from rock's 'condition of possibility', this undo (it) yourself pop puts into question ALL conditions of possibility, and with them the very concept of conditions of possibility.

This is happening, now, but it can't be, it's Impossible....

It can’t carry on, so the reality principle tells us.

And this time the reality principle will win.

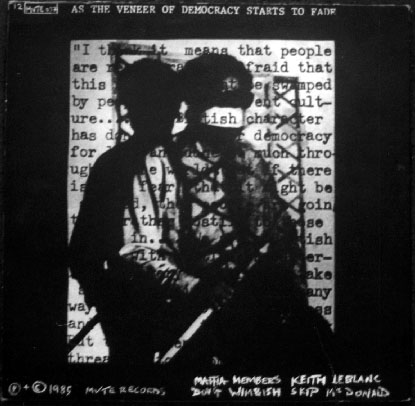

Play HYPNOTIZED by MARK STEWART AND THE MAFFIA

PART 5: HYPNOTIZED

Zizek:

'In post-liberal societies ... the agency of social repression no longer acts in the guise of an internalized Law or Prohibition that requires renunciation or self-control; instead, it assumes the form of a hypnotic agency that imposes the attitude of "yielding to temptation" - that is to say, its injunction amounts to a command: "Enjoy yourself!" Such an idiotic enjoyment is dictated by the social environment which includes the Anglo-Saxon psychoanalyst whose main goal is to render the patient capable of "normal", "healthy" pleasures. Society requires us to fall asleep into a hypnotic trance...'

Lockdown. 1985. The veneer of democracy fading on TV.

Miners lined up against cops and paramilitaries.

The Miners represent history. A history that is about to end.

Their defeat will seal it.

It’s been planned for years. Capital’s agents consolidating the next phase.

Call it postFordism, neoliberalism, capitalist realism.. It’s already underway.

Capital has solved the labour problem.

So, in a sense, this is all for show.

“The end of the world, the end of all our worlds.”

All of this will come back

(Everything comes back is the law of Web 2.0)

It will come back, but as its own simulation

Put through special digital filters that give it an even more aged appearance, and mark it as someone else’s history.

But all history is someone else’s history now.

We are no longer partisan antagonists.

We have joined the debate.

There are no spectators, because we are all participants.

Plugged in, texting our vote, paying attention.

Cut back to 1985. Mark Stewart, five years after the end of The Pop Group.

His sound now stiffened with an adamantium exo-spine imported from New York hip hop.

He cuts up the tapes by hand, increasing the distortion and abrasion.

He crudely splices them together again, but so that you can hear the joins.

Burroughs citations and Burroughs methodology.

Simulating the noise of a polis acrid with the smoke of antagonism.

Alongside the recanted facts - 7% of the population own 84% of the wealth - radio samples, ephemeral fragments of longing, disco quotations -

“Hypnotized” is a sonic collage as anti-love song, a demystification in the spirit of Gang Of Four’s “Anthrax” though far less measured.

Stewart is still howling from the outside

Against domicile, domesticity

Against the privatization of all space.

Against the prison of another’s eyes.

Against capital’s substitute for the sacrament

Heaven must be missing an angel…

Play HYPNOTIZE by Scritti Politti

I forget to believe in heaven, when I look at you girl

First of all, note the comparisons.

Like Stewart‘s Maffia, the new electro-reinforced Scritti has a hard hip hop exoskeleton.

It also is not a love song so much as an examination of love,

But what Green inscribes is the Lacan lack of the lover’s talk -

The love letters necessarily left incomplete

He doesn’t rail against romance from outside.

For Green now,

back from a breakdown,

totally reconstructed like his music,

there is no outside.

Only a Moebian band, an endless, seductive surface to play with, unsettle and be unsettled by.

From a concern with the inverse interplay of the means of production and the production of meaning

to a revelling/ unravelling in meaninglessness.

How could your nothings be so sweet?

All wordplay turns to non signifying honey in Green’s mouth, his voice now no longer mockney Robert Wyatt but modelled on Michael Jackson

A continual slide between two types of Non-Sense: the nonsense of 'the lover's discourse', the nursery-rhyme-like reiterations of baby-talk phrases that are devoid of meaning, but which are nevertheless the most important utterances people perform or hear;

and also the nonsense of the voice as sound, another kind of sweet nothing.

Green’s voice almost prevents you hearing the lyrics except as senseless sonorous blocks, mechanically repeated refrains.

As opposed to Self-consciousness, a 'reflexivity without a self (not a bad name for the subject').'

Only the void, the voice and the signifying chain, unraveling forever in a shopping mall of mirrors, a whispering gallery of sweet nothings...

It was Paul Oldfield, in his 1989 essay “After Subversion: Pop Culture And Power”, who most effectively described Scritti’s strategies at this time.

- Scritti’s departure from the independent business and their change of styles has been interpreted as part of the New Pop’s entry-ism, its sanctioning of the mainstream as the place in which to put across ideas. But more than that, it was an abandonment of both the ideology of independence and that of entry; the grafting of new aims onto the charts, ‘working from within’. Scritti work with pop, in its closure, not against it, nor do they co-opt it for our enlightenment. Scritti understand that order isn’t so monolithic that only utopian demands or provocations are possible. There’s subversive work to be done on the powers we exercise over ourselves. Nor is this an oppositional practice. Their music exploits the breaches and deficiencies that are already there in the prevailing discourse. For Scritti’s Green Gartside, pop music can always be subversive of the imperatives of meaning. He attempts to elude the closure or reclamation of pop’s pleasure. Instead of any fulfilment or resolution, Scritti’s music delivers the bliss of a lover’s discourse in all its ellipses, contradictions and repetition, its endless pursuit of the unattainable object. The disembodied, depthless, non-linear effects, and the borrowings of pop’s language of love try to undo desire’s usual articulation in coherent drives and stable identity while reinscribing the very ’soul’ language that’s used to heal and complete the self in today’s pop: the sweet nothings heard beside, within the sexual healing. But such an immaculate pop and so delicate a deconstruction, which hardly seems to touch on institutions, may be hard for consumers to experience as a shaking or subversive effect.

It may indeed have been hard for consumers to experience this as a shaking of a subversive effect.

Capital eats deconstruction for breakfast.

Green’s hammer and popsicle pop doesn’t even cause the tungsten-carbide stomach a moment’s indigestion.

On the contrary

Specifically via its influence on Jam and Lewis's production of Janet Jackson's epochal Control, but more generally through its entrepreneurial intuition that the flesh and blood of (what was then called) Soul could be sutured with hip hop's artificiality and abstraction machine, Cupid & Psyche instituted a 'new paradigm' for globalized Pop

.

Skank Bloc Bologna has become the Global retail arcade of capital.

Cupid & Psyche is chillingly impersonal, but in a way that is much different to the staged impersonality of Kraftwerk, Numan and Visage which fascinated black American hip hoppers, techno and house pioneers in the early 80s.

Has anyone ever been moved by Green’s love songs?

Scritti's erasure of Soul goes by way of a neurotically note-perfect, ultra-fastidious simulation of a hyper-Americanised 'language of love'.

It is no longer a matter of technical machines versus real emotional beings, but of 'authentic emotion' as itself the refraining of signifying and sonorous machines

Narcissus in cyberspace

But the way had already been prepared.

Play LIONS AFTER SLUMBER by SCRITTI POLITTI

PART 6: LIONS BEFORE SLUMBER

In retrospect, “Lions After Slumber” and the Songs To Remember album which succeeded it can only be heard as templates for the Cupid & Psyche sound

An unlearning of the unlearning of pop

A way back in, Green strategising how a pop stripped of experimentalism could still disturb

A narcissistic miscalculation, a self-delusion more than an act of deliberated deception

The Shelley quotation at the end of this “little relativist hymn” is something of a non sequitur.

The invocation of collectivity, the ‘unvanquishable number’, follows a litany, a list, which all begins with my.

Could it be, in fact, “Lions After Slumber” is not about rousing a collective, but about duping and doping it back into somnambulism?

Green’s little list as the heap of fragments that we

Who are no longer a we

Now are

My hope and my ice scream

My tomorrow and my temperature

My lips and my selfishness

Myspace

Now no mirror you look in is shattered

You find yourself everywhere perfectly reflected

You forget

You have forgotten

Only a distorting mirror can wake you.

May 28, 2009

Energy flashbacks (and flashforwards)

Image via Gutterbreakz

1. Now a dead battery "I used to go raves when I was younger, I went through that whole explosion in electronic music from 1987 to around 1992-93 when it seemed like there was new genre every single week. It was an amazing time in music to hear so many things happening and so many new possibilities opening up and to see and feel the energy of new music exploding on dancefloors and in clubs. I think The Death Of Rave is about the loss in that spirit and a total loss of energy in most electronic musics across the board. I feel sorry these days for people when I go to clubs as that energy isn't there any more, it's different energy now ..." - James Kirby aka The Caretaker in The Wire this month.

2. Impenetrably arcane Gutterbreakz on Sapphire And Steel: "How anything as impenetrably arcane as this could ever have been considered mainstream family viewing remains one of the great cherished mysteries of what we might call the 'Ghost Box era'."

3. Nostalgia for modernism, again The discussion about nostalgia is really becoming tiresome. As has already been argued here, here and here, simply comparing the present unfavourably with the past is not nostalgic in any culpable way. It is the tendency to falsely overestimate the past that makes nostalgia egregious: but, one of the lessons of Andy Beckett's superb When The Lights Went Out is that, in many ways, we falsely underestimate a period like the 70s (Beckett in effect shows that capitalist realism was built on a myth-monstering of the decade). Conversely, we are induced - by ubiquitous PR, whose blank, joyless positivity has a crushingly depressing effect, even though (or rather precisely because) no-one believes it at the level of content - into falsely overestimating the present. The Caretaker's Theoretically Pure Anterograde Amnesia echoes Jameson's remarks on postmodernity : it is precisely the failure of historical awareness - under pressure from a cyberblitzing blip time that has no long term memory - that leads to the rise of nostalgia. Those who can't remember the past are condemned to have it resold to them forever.

But I say with total confidence that the decade we've just lived through will be recognised - and not in the far distant future, but very soon - as the worst period for (popular) culture since the 1950s: a decadent, despondent dead zone in which conformity was rebranded - in the media's lickspittle jester prattle - as 'light, upbeat, irreverent'.

To reiterate (because the point is germane not only to the architectural/ gatekeeper furore, but also to the hardcore continuum and Sonic Youth discussions), and to state what ought to be obvious : we are in a culure that is formally nostalgic to an astonishing degree. In this present which is so given over to pastiche, pointing to previous historical moments can act as a resistance to pervasive, normalised nostalgia. The present is not necessarily the modern; that is the postmodern condition reduced to a formula. The correct perspective on the past in this respect can only be got at by considering it as a rival (to the) present. Imagine the two moments as competing presents, as it were laid out side by side: which one would you choose? Which one contains the most possibilities? And the past moment is not grasped if it is flattened out to the collection of dead museum artefacts that the distorting lens of retrospection reduces it to ("one day all that will be left of it will be…records"): no, to grasp that moment properly involves considering the futures that it projected. Hauntology has always been about those projected futures; and it is by comparison with those lost virtual futures that the present must be judged harshly. But soon we will no longer need the spectral guides any more.

4. SYmptoms. I said I wouldn't write about Sonic Youth again, and I will try not to say much more. But I can refer you to what others have written. And this, from someone formerly of this parish: "I mean, sure, if you hit your guitar with a drum stick once, or twice, it might be irruption/uproar, formal sur-prize, but if you do it for 25 years ...? isn't it just 'avant garde' Status Quo-ism?"

I can also clarify my objections. It is not SY's being mainstream that irks me - it is a perfectly honourable aim to be "an explosion in the heart of the commodity", as the Pop Group wanted to be - it is their occupying a comfortable position of hegemonic domination while disavowing it which seems to me definitional of avant-conservatism (a phrase that I have taken from Frieze's Dan Fox). Could Sonic Youth's rockist devotees enjoy their records in the same way without the belief that they are 'alternative'?

Avant-conservatism rests on an equivocation between structural position and formal invention. Being 'alternative' in the way that Sonic Youth now are is a structural position, essentially a marketing category; it bears no relation to formal inventiveness. For if SY's ye olde formal inventions qualify them as avant-garde in 2009, then what is to disallow anything on the rock nostalgia circuit from making the same claim - it, too, was new once. (cf Joe Stannard's - sympathetic but seemingly deeply dissatisfied - review of The Eternal in The Wire this month, which practically sighs with frustration at SY's enervation.)

5. Hate's not your enemy, love's your enemy Zone is quite right that Lydon's scrawling of "I Hate" onto a Pink Floyd t-shirt was "the definitive punk gesture in the way it hijacks a readymade, defacing and desecrating a complacently commodified consensus." But it was the desecration of the consensus within the counterculture that was crucial. Avant-conservatism, not the mainstream, is always the proper object of any countercultural revolt. What has to be continually incinerated is precisely this space of comfortable opposition to the mainstream. Rotten's gesture was all the powerful if Lydon the biographical individual actually at some point liked and respected Pink Floyd. To desecrate something not in spite of the fact that it is 'good' but precisely because it is 'good', to destroy the settled consensus about how value is assigned, to scorch all earths, this was punk's nihilative impetus, its traumatic opening up of a space beyond good evil - something that is far more alien to our restoration world ("would you like a Sonic Youth CD with your frappucino, sir?") than it was to 1976.

6. Hurry up please, it's time. But the restoration world is finished - even though, like the father in the dream recounted by Freud, it does not yet know it is dead. Ladies and gentlemen, can't you see that the restoration scenery around you is just dust and pasteboard? It's coming apart in clumps. The OedIPod, once the supremely secure means by which all outsides were transformed into the inside, is cracked open. And we who have been guided across the desert by ghosts crouch like commandos amidst the ideological rubble of the new Year Zero...

May 18, 2009

'... without any consequence for the individual villains'

At the European Business Ethics Network UK conference last month - at which I was lucky enough to be a keynote speaker (I will post up the presentation that I gave there very soon) - Campbell Jones gave a paper entitled "The Subject Supposed To Recycle". In posing the question, who is the subject supposed to recycle? Campbell was denaturalising an imperative that is now so taken for granted that resisting it seems senseless, never mind unethical. Everyone is supposed to recycle; no-one, whatever their political persuasion, ought to resist this injunction. The demand that we recycle is precisely posited as a pre- or post-idelogical imperative; in other words, it is positioned in precisely the space where ideology always does its work.

But the subject supposed to recycle, Campell argued, presupposed the structure not supposed to recycle: in making recycling the responsibility of 'everyone', structure contracts out its responsibility to consumers, by itself receding into invisibility. The discussion after Campbell's paper turned on the question of agency - since "corporations are made up of individuals" doesn't this mean that there is always hope for change? But it seems to me that "individual" is best defined as one incapable of acting. I would suggest that, at this time when the appeal to individual ethical responsibility has never been more clamorous - in her new book, Judith Butler Frames Of War uses the term "responsibilization" to refer to this phenomenon - it is necessary to wager instead on structure at its most totalizing. Instead of saying that everyone - i.e. every one - is responsible for climate change, we all have to do our bit, it would be better to say that no-one is, and that's the very problem. The cause of eco-catastrophe is an impersonal structure which, even though it is capable of producing all manner of effects, is precisely not a subject capable of exercising responsibility. The required subject - a collective subject - does not exist, yet the crisis, like all the other global crises we're now facing, demands that it be constructed. Yet the appeal to ethical immediacy that has been in place since at least 1985 - when the consensual sentimentality of Live Aid replaced the antagonism of the Miners Strike - permanently defers the emergence of such a subject.

Similar issues were touched on in Armin Beverungen's paper on The Parallax View. Armin saw Pakula's film as providing a kind of diagram of the way in which a certain model of (business) ethics goes wrong. For The Parallax View is in a sense a meta-conspiracy film: a film not only about conspiracies but about the impotence of attempts to uncover them; or, much worse than that, about the way in which particular kinds of investigation feed the very conspiracies they intend to uncover.

The Parallax View came to my mind frequently when watching the Red Riding films, and all three could be seen as compulsions to repeat Pakula's film. 1983's apparently redemptive coda might have constituted a failure of nerve, but 1974 and 1980 reiteratively traced the circuit of fatality which The Parallax View described with such grim elegance. It was perhaps 1974 - with its brutalist backdrops, and swaggering journo-rebel protagonist ultimately framed for the very crime he is investigating - that most echoed Pakula's film (appropriately since 1974 was the year in which not only The Parallax View, but also The Conversation and Chinatown were released). Yet none of the Red Riding films achieved quite the satisfying horror that The Parallax View reached at its moment of bleak closure. It's not only that the Beatty character is framed/killed for the crime he is investigating, neatly eliminating him and undermining his investigations with one pull of a corporate assassins trigger; it's that, as Jameson noted in his commentary on the film in The Geopolitical Aesthetic his very tenacity, quasi-sociopathic individualism make him eminently frameable.

The terrifying climactic moment of The Parallax View* - the silhouette of Beatty's anonymous assassin against migraine white space - for me now rhymes with the open door at the end of a very different film, The Truman Show. But where the door in the horizon opening onto black space at the end of Weir's film connotes a break in a universe of total determinism, the nothingness on which existentialist freedom depends, The Parallax View's final "open door ... opens onto a world conspiratorially organized and controlled as far as the eye can see" (Jameson). This anonymous figure with a rifle in a doorway is the closest we get to seeing the conspiracy (as) itself. The conspiracy in The Parallax View never gives any account of itself. It is never focalised through a single malign individual (compare, for instance, the grandstanding justification given by Richard Widmark's hospital administrator at the end of Michael Crichton's Coma, or even the opening scene of 1983, with pere-jouissance Bill Molloy holding court). Although presumably corporate, the interests and motives of the conspiracy in The Parallax View are never articulated (perhaps not even to or by those actually involved in it.) Who knows what the Parallax Corporation really wants? It is itself situated in the parallax between politics and economy; is it a commercial front for political interests, or is the whole machinery of government a front for it? It's not clear if the Corporation really exists - more than that, it's not clear if its aim is to pretend that it doesn't exist, or to pretend that it does. As Jameson observes, what Pakula captures so well in The Parallax View is a particular kind of corporate affective tonality:

- For the agents of conspiracy, Sorge is a matter of smiling confidence, and the preoccupation is not personal but corporate, concern for the vitality of the network or the institution, a disembodied distraction or inattentiveness engaging the absent space of the collective organization itself without the clumsy conjectures that sap the energies of the victims. These people know, and are therefore able to invest their presence as characters in an intense yet complacent attention whose centre of gravity is elsewhere: a rapt intentness which is at the same time disinterest. Yet this very different type of concern, equally depersonalised, carries its own specific anxiety with it, as it were unconsciously and corporately, without any consequences for the individual villains.

... without any consequences for the individual villains... How that phrase resonates just now - after Hillsborough (whose grisly catalogue of police incompetence, malice and mendacity was exhumed again recently because of the twenty year anniversary), after Jean Charles De Menezes, after Ian Tomlinson, after the banking fiasco. And what Jameson is describing here is the mortifying cocoon of corporate structure - which deadens as it protects, which hollows out, absents, the manager, ensures that their attention is always displaced, ensures that they cannot listen. The haunting power of David Morrissey's rendering of Maurice Jobson in the Red Riding films came from the way that he caught that abstracted corrupt/ corporate blankness just so. The delusion that many who enter into management with high hopes is precisely that they, the individual, can change things, that they will not repeat what their managers had done, that things will be different this time; but watch someone step up into management and it's usually not very long before the grey petfification of power starts to subsume them. It's here that structure is palpable - you can practically see it taking people over, hear its deadened/ deadening judgements speaking through them. And surely we have all felt the effects of structure whenever we assume a so-called position of responsibility: we immediately find ourselves second-guessing our responses, anxiously concerned about whether we are doing what It wants, never sure if we are measuring up...

But we shouldn't rush to impose the individual ethical responsibility that the corporate structure deflects. This is the temptation of the ethical which, as Zizek suggested at the Birkbeck Communism conference, the system is using in order to protect itself - the blame will be put on supposedly pathological individuals, those 'abusing the system' (and then deflected onto other targets altogether) rather than the system itself. But the evasion is actually a two-step procedure - since structure will often be invoked (either implicitly or openly) precisely at the point when there is the possibility of corporate individuals being punished. At this point, suddenly, the causes of abuse or atrocity are so systemic, so diffuse, that no individual can be held responsible. And now we are back at Hillsborough and the Jean Charles De Menezes farce, with the individual policemen walking free. But this impasse - it is only individuals that can be held ethically responsible for actions, and yet the cause of these abuses and errors was corporate, systemic - is not only a dissimulation: it precisely indicates what is lacking in capitalism. What agencies are capable of regulating and controlling impersonal structures? How is it possible to chastise a corporate structure? Yes, corporations can legally be treated as individuals - but the problem is that corporations, whilst certainly entities, are not like individual humans, and any analogy between punishing corporations and punishing individuals will therefore necessarily be poor. And it is not as if corporations are the deep-level agents behind everything; they are themselves constrained by/ expressions of the ultimate cause-that-is-not-a-subject - capital.

Let's be in no doubt. There are certainly conspiracies. I've been a victim of one in the workplace (1980 made for uncomfortable viewing, not least at the moment of reversal when Hunter, the man charged with investigating corruption, suddenly finds himself the object of a counter-investigation - but at least I only lost my job, I didn't get my house burned down or get shot, for which I suppose I should be grateful). But the issue with conspiracies under capitalism is: does anyone really think it would be better if we replaced the whole managerial and banking class with a whole new set of ('better') people? Surely it is evident that the vices are engendered by the structure, which is one reason that Marxism is preferable to any moral critiques of capitalism. We also need to ask how it is that particular conspiracies can be successful. Current conditions favour conspiracy - as Nick Davies shows in Flat Earth News the media, rather than uncovering conspiracy (as mythologised in Pakula's All The President's Men), now tend instead to obediently propagate whatever PR hype they are fed. Which is why we should take a step back and ponder why it is at this precise moment that the stories about MPs' expenses have emerged. M John Harrison suggests that the 'uncovering' of the irregularities in MPs' expenses is not the result of intrepid investigative reporting, but is a (successful) attempt at news management: cover-up in the guise of revelation.

- The bankers stole our money: but the MPs have stolen “the taxpayers’ money”. Instant uproar.

The bankers stole more. They didn’t fiddle a meagre £10,000 here & there. They got away, personally, with fortunes. They didn’t fiddle a mortgage; they fiddled millions of mortgages & then collected £7 or £8 million in “pensions” as their price for leaving the institutions they had wrecked.

They got the taxpayer to pay them to go. How is that not “stealing the taxpayers’ money” ?

Paying MPs is a form of public spending. When we are stupid enough to vote the Tories back in, our rage against MPs will be redirected by them on to every other form of public spending. The bankers will get away with it. The blow that should have fallen on them will be received instead by a handful of hapless prats who got their fingers in the petty cash. Result.

Our frustration with the bankers, our rage against the recession they caused, will be refocussed on that arch enemy of Toryism, public spending. Because MPs have been shown to be corrupt, all public services will be blackened by association, then cut: it will seem perfectly logical. The disadvantaged, their ranks swelled by hundreds of thousands of victims of the bankers, will be punished for the sins of the advantaged. As usual, ordinary people will be deftly turned into their own enemies. Fantastically elegant politics.

Charlie Brooker's Newswipe has shown how Downing Street and the tabloids choreograph particular stories, so that the newspaper 'outrage' is factored in from the start. Like Adam Curtis, Brooker has also been dogged in identifying the way in which emotionalised and personalised content increasingly displaces news in the old sense. Bleary sentimentalism blocks any thinking about real abstractions; except when those abstractions are wheeled on as a mystified exculpation in the form of the global economy, which appears to be as sublime, mysterious and incomprensible as any theological entity, and less susceptible to human will than even the weather.

*(The climax of The Parallax View is available on online, but the clip can't be embedded, so you'll have to go YouTube to see it.)

__________________________________________________________________

Incidentally, while we're (back) on Red Riding... I've been meaning to link to this excellent Fantastic Journal post for ages now. FJ draws out what I most appreciated in the Red Riding films: their "specifically visual intelligence".

May 10, 2009

Avant-conservatism

OK, this is the last thing I'm going to post on Sonic Youth - there are so many more interesting things to write about just now. But I must take up some of the issues raised by Zone's reply. I'd also like to draw people's attention to Marcello's interesting remarks on SY (which are particularly good in relation to my improv-provocations).

Zone's attempt to psychopathologise my SY-disdain, to attribute it to the loathing only a double can provoke, would be more convincing if it weren't based on SY and I "sharing an admiration for whole swathes of postpunk, pop, and modernism low and high (Burroughs, P. K. Dick, William Gibson, Joyce, The Carpenters etc)." The list is hardly specific to either SY or me; rather, it enumerates preferences that are practically ubiquitous amongst people of a certain age with 'countercultural' sympathies. If he'd included John Foxx and Visage in the list, I might have been persuaded. (Incidentally, while we're on electronic music: my point was not that electronic music is immune to entropy - a claim that would undercut everything I've written about hauntology and the argument I made in New Statesman only last week. The point, rather, was that electronic music is not tied to a romanticism of youth in the way that rock is - so that Kraftwerk in their 60s does not produce the same frission of grotesquerie that the geriatric Stones and Stooges do.)

Contra what Seb in Zone's comments suggests ("I'm ... glad to see someone cook up a convincing explanation of K-Punk's oddly intense enmity towards SY"), it's not my hostility towards SY that requires explanation - it's SY's hegemonic support that needs to be accounted for. But I think that this characterisation of my response tells its own story. If a group were genuinely challenging and experimental, "oddly intense emnity" would surely be expected from some quarters. But the point is that no-one, even their own supporters, really expects SY to provoke any sort of strong affect at all, just elicit a bland admiration. They're on our side, they're good sorts. And the fact is, it is indeed difficult to summon up any affect for them. The emnity is a second-order response to my first order action, which is one of boredom. (A boredom that I strongly suspect is shared by even their most ardent fan - could such a fan sincerely claim that the thought do we really need another Sonic Youth record? has never come to mind?) This renormalisation of boredom, this re-establishment of consensus around 'accepted standards', is precisely what is so pernicious about Sonic Youth now. They represent the embourgeoisiement of the rock avant-garde, its disconnection from overreaching, intemperance, intolerance and antagonism.

"Sonic Youth are banished from ‘mainstream’ taste forever," Zone argues. "Kim Gordon in growl mode, the abstract-expressionist noise breaks, performance artists Bob Flanagan and Sherry Rose wiping their arses with stuffed toys on Dirty's artwork." But Zone's inverted commas around 'mainstream' are entirely necessary - for the idea there is a mainstream which repudiates Sonic Youth is the fundamental (rockist) fantasy which feeds their allure. Kim Gordon in New Statesman last week: "Are Sonic Youth political? Well, they are, in that they offer an alternative to mainstream music." Well, they may not have hit singles (but neither did the prog dinosaurs of the 70s); but here they are on Later With Jools Holland; here they are doing compilations for Starbucks; here they are, the darlings of the broadsheet press, their pastiche-of-themselves records not exactly guaranteed a good review, but always automatically accorded event status. In what way is the so called mainstream perturbed by any of this? In what way, in the decentred era of web 2.0, is this not the mainstream? Their avant credentials rest on a few hoary old formal innovations - just as the prog rockers' did in the early 70s. SY have disconnected experimentalism from social and existential maladjustment, just as prog rock did. But while punk annihilated prog after a mere half a decade of flatulent complacency, Sonic Youth are still lauded as countercultural heroes even though they have been making variations on the same record for over twenty years now.

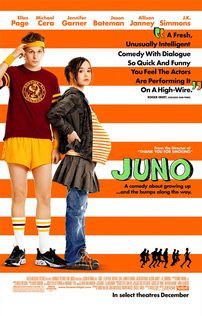

SY's precise function for Restoration culture is to be a hypervisible simulation of an alternative within the mainstream. That is why Juno provides such a depressingly accurate picture of certain impasses in US alt.rock culture: a supposedly smart alt.teen (not so smart that she avoids getting pregnant, though) as poster girl for reproductive futurism, giving up her child to baby-crazed professional, whose husband - a failed rocker now miserably writing advertising jingles - turns her onto Sonic Youth. The fact that Juno - who is into Patti Smith and The Stooges - has mysteriously not heard of Sonic Youth is the key to their fantasy positioning. When she falls out with the husband, Juno says that she "bought another Sonic Youth CD and it's just noise" - at this point, everyone's happy: SY are namechecked in an indie-mainstream commodity, but posited as something that is ultimately too extreme. There is no more stultifying mode of cultural conservatism than this avant-conservatism.

SY's popularity provides another angle on the hipster debate from last year. As Ray Brassier, someone who shares my dismay and disappointment about SY's pre-eminence, puts it (via email):

- there's a perfect sociocultural congruence between SY as individuals and their audience: that burgeoning of a vast college educated middle class audience for "alternative rock" in the 80s and 90s: graduates wanting something a little bit artier and recherche than pop, metal or hardcore, but nothing too foreboding or intimidating: SY fitted the bill perfectly: indeed, Moore and Gordon are the mirror image of their audience: nice, vaguely bohemian/arty middle class urban professionals: Gordon's links to the NY artworld very symptomatic: and of course art too became an attractive and materially rewarding profession for middle class hipsters in the 90s....

Seb wonders how I can

- be so up on The Fall, The Pop Group, and the Birthday Party and have no affection for Sonic Youth's music? It's barely a bunny hop from "Mere Pseud. Mag Ed" to "Kissability", or from "The Friend Catcher" to "Death Valley '69".

I'd reverse this question: how can anyone exposed to the bilious schizo-intractability of The Fall, the phantasmagoric derangement of The Pop Group or the spasmodic abjection of The Birthday Party possibly lower their expectations such that they are satisfied with what Ray calls the "tepid, flannelly, terminally uninvolving college alt-rock" of Sonic Youth?

What's at stake here is the very difference between pulp modernism and postmodernism. The Birthday Party, The Pop Group, The Fall up to 1983, were all impelled by the conviction that the only way in which rock could continue to justify its existence was by perpetually reinventing itself; they were death-driven forward by a nihilative motor which wouldn't allow them to resemble anything pre-existing, even themselves: never settle, never repeat yourself, never give the audience what they want, were the unwritten maxims inducing them into further convulsions. It's easy to forget now, after Smith and Cave's Sunday supplement canonisation, how divisive this music was, how it engendered revulsion and denunciation as much as adoration, how it shattered any sensus communis. And then there is the Vision thing: listening to The Fall, The Birthday Party and The Pop Group, you tuned into a unique way of seeing the world - whereas SY offer only a bleary, weary confection of familiar alt.rock postures and signifiers. Importantly, also: The Fall, The Pop Group and The Birthday Party kept the Sixties behind them. (It's not a coincidence that the moment that The Fall started faltering was marked by a Stooges' citation: the hijacking of the "I Wanna Be Your Dog" bassline in Wonderful And Frightening World's "Elves".) Punk and postpunk's significance was to have overcome the Sixties, to have fingered the Sixties as the problem, whereas SY, with their even handedness and informed good taste, re-established a continuum between punk and the Sixties, mending the bridges that punk had incinerated.

It's true that my view of 80s SY is to some extent a retrospective judgement, intensified by the fatigue that their slogging on and on has produced. For a while, I did dutifully go along with the idea that Sonic Youth mattered, until I had to admit - to myself - that they completely left me cold. I sold all my Sonic Youth records bar Death Valley 69 - everything from the early EPs up to Sister and EVOL - in the late 80s; funnily enough at the same time as I offloaded my JAMC records, partly so I could afford to buy The Pop Group LPs, then available very rarely and very expensively in secondhand shops. Most of the time when I've sold records, I've ended up regretting it at some later time, but I can honestly say that I've never once missed the SY LPs. That's because, to quote Ray again, "There was never a moment when they were 'good': their 'noisy' period was never anything but feeble rocked-up no-wave pastiche: Daydream Nation is most grotesquely overrated work in living memory."

Zone points out that SY

- formed from the ashes of No Wave, an aggressively Year Zero project, but No Wave was such an extreme standpoint that it imploded almost as soon as it had begun – it was a scene that lasted barely months so stringent and un-livable was its own fragile logic.

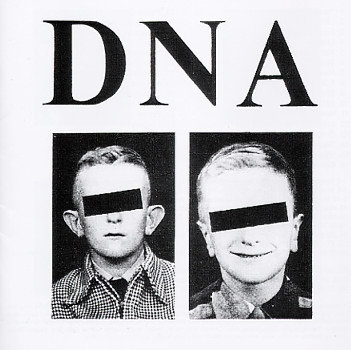

This is it, this is the crux. SY's very existence involved a compromise, a sense that things had gone too far; in presupposing the 'unlivability' of No Wave, it asserted a resurgent reality principle. Against this, I quote the opening paragraph of the director's cut of Ray's review in The Wire of Moore and Byron Coley's No Wave book:

- 30 years on and the short-lived musical catalepsy christened ‘No Wave’ still stands as a sobering reminder of a realm of possibility that rock has had to abjure in order to perpetuate itself. Although regularly lumped in with ‘post-punk’ ... No Wave was in fact more or less exactly contemporaneous with punk; yet the distance between Teenage Jesus and the Clash in 1977 is the same as that between Webern and Vaughan Williams in 1927. Just as the cold but coruscating nihilism exhibited by Teenage Jesus and the Contortions relegated punk to music hall oafishness, the clinical asperity embodied by Mars and DNA withered the residual romanticism of post-punk, rendering much of it pre-emptively redundant. Mars still make Sonic Youth sound like Status Quo. Better for beat music to have expired in the terminal throes of Mars’ ‘N.N. End’ than to have limped on ignominiously into the persistent vegetative state known as ‘independent rock’. Routinely patronized as an unpalatable and ultimately sterile exercise in petulant extremism, or derided as a symptom of ‘formal exhaustion’ (by Springsteen fan Robert Christgau, inexplicably lent credence in this volume), No Wave’s intractable negation of R&R tradition pointed to uncharted territories that continue to haunt a terminally atrophied rock culture now, 30 years of interminably recycled cliché later.

Better for beat music to have expired in the terminal throes of Mars’ ‘N.N. End’ than to have limped on ignominiously into the persistent vegetative state known as ‘independent rock’. There was no need for rock to have survived. If it was a case of 'that or die', why not choose death? But even in 1984, retrenchment was by no means the only possible strategy: compare SY with their NY contemporaries Swans - a group who, even in the mid-80s, maintained a ferocious fidelity to No Wave's austere interdiction against reiterating the past. Swans literally prolonged rock's dead end into a inhumanly distended, super-tense grind, astonishing and unprecedented in its brutal starkness.

Punk, Zone writes,

- the real touchstone for SY (and No Wave), was rhetorically a tabula rasa, but surely everyone knows by now that punk was no Year Zero: it created its own precursors for you wholesale: Jonathan Richman, the VU, The Stooges, the mods whose drainpipe jeans and skinny ties Blondie would hunt down in thrift stores, The Who, covered by Patti Smith (in a b-side which pretty much invented, explored and foreclosed upon the entire musical ground of 90s riot grrl). And who compiled Nuggets? Patti Smith’s guitar player, Lenny Kaye. Now that's what I call curatorial.

But the most interesting trajectory out of punk involved the rejection of this year zero in favour of a series of new year zeros, each of them razing settled rock (and rock) history by inventing new precursors. SY, meanwhile, operated by precisely not creating their own precursors but in bolting an already-constituted punk lineage onto other established rock and alt. canons. Curating can have an important function to play, but with SY there has been a conflation of art and curatorialism - the alibi for their music's increasingly poverty at a textural and textual level is the way it supposedly makes a wider audience aware of marginal material. Sonic Youth are 'art' in all the worst senses (they possess a certain insitutional prestige, a certain standing and position, a cetain set of meta-rationales for what they do); but they are not art in the sense that there is a compelling reason for them to exist - there is no more at stake here than just another cool leisure product with all the right credentials.

May 04, 2009

My mind it ain't so open

|  |

I'm glad someone called me on the deliberately provocative, "boldly counter-intuitive and funny ... elision of Sonic Youth with Primal Scream and Oasis" in my review of the dreadful Brand Neu! 'tribute' album in The Wire 303. I'm particularly glad that the one doing the calling was ZoneStyxTravelcard (who is aka one of The Wire's best writers, but I'll keep quiet about his meatworld ID as I'm not sure if he wants it to be outed yet...) (Incidentally, there are some interesting convergences between what I said in the Brand Neu! review and Simon's recent

When I said above that the judgement on Sonic Youth was deliberately provocative, I didnt mean it was false. I realised when I wrote the review that dating the start of the fall from grace so early - with Bad Moon Rising rather than the obviously formulaic later phase certainly consolidated by the time of Goo - was risky. But Zone... has managed what, for the last twenty years has been all but impossible, and sparked my interest in Sonic Youth again. Who could not be beguiled by this description of Bad Moon Rising?

- BMR is the point at which their tunings, atonal and droning, blossom into dazzling synaesthetic iridescences. They sound, literally, uncanny – with strings tuned to the same note but fractionally apart, they create their own doubles, an unheimlich shadow sound, like a transparent overlay just out of position. Playing Stoogoid riffery in a harmonic template borrowed from free jazz and serialism, one that smashes the overdetermined limits of the pentatonic, they make discord sensual in previously unheard ways. Alex Ross may take issue with this, but I think BMR is the point where Sonic Youth in effect reconnect discord with the body, restoring to it a libidinal force which you hear in The Rites of Spring, but which the cold geometries of Schoenberg and Webern subsequently evacuated.

This, plus Zone's elaboration of the brilliant concept of "pyschopathology of place" further in the post, is precisely how I wanted to hear Bad Moon Rising, but never quite could, even then. And listening to it again this week, it sounds if anything even weaker than I remember it. The voices of Moore and Gordon have always blocked my enjoyment of Sonic Youth; even when the music achieves the oneiric uncanniness described by Zone, the spell is broken by Moore's hipster-slacker drivel or Gordon's hectoring shout. But it was the fact that they could once have claimed to have been a continuation of postpunk's popular experimentalism that allowed their retro-necro reverence and referencing to have such force. SY had enough credibility to legitimate the turn to the rearview mirror - the likes of Primal Scream and Oasis, who have never been original or groundbreaking, could then follow in their wake. On Bad Moon Rising, as Zone rightly argues, it isn't the music so much as the tissue of references that is backward looking. Except of course for that distorted sample of The Stooges "Not Right" at the start of "I Love Her All The Time" - and you could argue that the whole of the last 25 years conversion of experimental rock into part of the heritage industry (culminating in the grotesque return of The Stooges themselves as geriatric teenagers, the All Tomorrow's Parties retrofests, everything so consummately lambasted in Tony Herrington's review of The Stooges' The Weirdness in The Wire a couple of years back) was bred out of that one act of citation. Not so much kill your idols, as put them on the festival circuit, forever. At this point, the postpunk and No Wave scorched earth intolerance for the past was gradually dismissed in favour of a widening of taste, a greater openness - hey, The Carpenters can be cool! cf the Immaculate Comsumptives' roughly contemporaneous turn to MOR. I'd be the very last person to dispute the profound greatness of The Carpenters, but there's a massive difference between being a person of good taste and being a great artist. As Nietzsche rightly argued, a certain kind of stupidity is necessary for all greatness, a preconditon for which is a deliberate narrowing of perspective, a refusal of 'well-roundedness'.

The same issue came up at the recent Roundhouse event celebrating the publication of Simon's Totally Wired a couple of months ago. Viv Albertine and Scritti's Tom Morley had an attitude towards the strictures and the strictness of the (post)punk period that stopped just short of outright hostility: every aspect of your life was under scrutiny, Albertine complained, your clothes, your sexuality, what you said... But when the music was played, its crystalline ascesis, its lucid abrasion, showed that dogmatism can deliver intensity whereas laissez-faire well roundedness produces precisely the bleary retrospection of postmodern rock. You couldn't admit to liking Neil Young, someone said - but that not being allowed to admit liking things, arbitrarily closing down aspects of the past even - no, especially - if they were 'good' was crucial to the drive to make something new.

It seems to me that Sonic Youth's very long career has been based almost exclusively on their being "people of good taste" - curators, in other words, who can turn a notionally ignorant audience on to cool stuff. I think this is subtly but decisively different from being a portal: a portal is itself intensifying, there is a mutual process of libidinization between the portal and what it opens onto, whereas SY now derive practically all their credibility from gesturing to artists more marginal than them. (Also - portals function most powerfully when they are transversal connectors between different cultural domains, e.g. fiction and music - whereas many of SY's references were to music, justifying the trend that will end up in mediocrities such as Starsailor parasiting credibility by association with great moments in rock history.) Ultimately, there's something very uncomfortable about SY referring to the likes of Darby Crash while continuing on a thirty year, very stable, career as professional musicians and dilletantes. The problem isn't quite that SY weren't self-destructive fuck-ups as that they seem to be so pathologically well-adjusted that the music doesn't appear to be performing any kind of sublimatory function for them. It isn't that they "don't mean it" so much as they only mean it, that, like the worst, most self-conscious meta-art, the work is reducible to a set of easily verbally explicable intentions. There is no sense, even in the early work as far as this listener is concerned, that the music is drawing on any unconscious material. (Improv and automatic writing are the worst ways to access the unconscious - discuss.) As Zone admits, like The Fall, SY have effectively pastiched themselves for the last two decades - and you have to ask: even if they were formally inventive in the first years of their existence , how can a group that is "combining and recombining previously-deployed moves into technically 'new' but very familiar shapes" be effectively differentiated from Status Quo? It's not SY's fault, for instance, that thelr (dreary and dreadful) cover of The Carpenters' "Superstar" should be cited as the apogee of cool in the smuggest teen film of all time, Juno - it may not be their fault, but it is symptomatic, and it tells us a great deal about the way in which they - and the model of alternative rock that they are the poster boys/girls for - functions in the current reality programme. We've got a situation where the word 'alternative' has been entirely co-opted by the rock/youth model of rebellion - something interestingly attacked by Timothy Brennan in his Secular Devotion, which I also recently reviewed in The Wire; "capitalism is youth", Brennan claims, in a beautifully provocative slogan. Rock is necessarily tied up with a romanticism of youth (whereas electronic music isn't, in part because of its 'cerebral' nature, as Mike Banks observed when I interviewed him). The problem posed by SY not being "junky fuck-ups" is by no means unique to them - it is inherent to the whole mythology of rock, which is why the sheer survival of The Stones/ Who etc has fatally undermined rock as a mythology, enabling its conversion into mere entertainment. It hardly needs pointing out that if there is a mainstream now, it is alternative rock - not only the manifestly appalling mealy-conservatism of BritIndie, but also and especially, the ostensibly more experimental likes of Sonic Youth, which is now actually "experimental" in terms of brand identification, not in terms of any formal properties.

May 01, 2009

'a very clever, velvet-gloved provocateur'

Jonathan Meades on Owen in New Statesman:

- This book is the deflected Bildungsroman of a very clever, velvet-gloved provocateur nostalgic for yesterday’s tomorrow, for a world made before he was born, a distant, preposterously optimistic world which, even though it still exists in scattered fragments, has had its meaning erased, its possibilities defiled. And which has posthumously been wilfully misrepresented.

I couldn't have put it better myself...