June 06, 2009

The Spy who never came in from the cold world

|  |

- And there are some of us, aren't there, who are ... nothing, who are so labile that we astound ourselves. We're the chameleons. I read a story once about a poet who bathed himself in cold fountains so that he could tell he actually existed from the pain of it. [...] People like that, they can't feel anything inside them: no pleasure or pain, no love or hate. They're ashamed and frightened that they can't feel, and their shame, this shame, [....] drives them to extravagance and colour. They have to feel that cold water. Without it, they're nothing. The world sees them as showmen, fantastists, liars, as sensualists perhaps, not for what they are: the living dead.

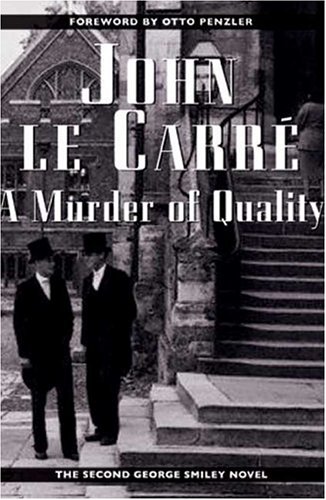

Listening to Radio 4's adaptation of le Carré's curious A Murder Of Quality (part of the station's dramatiase all of the George Smiley books, and one of the Smiley books I hadn't previously read), I was struck by how much that Smiley belongs in Dominc Fox's Cold World. Set in a public school, A Murder Of Quality sees le Carré (re)turning to the setting and structure of an Agatha Christie whodunnit. The teaming of the erudite Smiley with his local bobby sidekick could be a dry run for the partnership of the posturing Morse and the dull-but-loyal Lewis, although even in a novel as unsure of itself as A Murder Of Quality is, Smiley has a casual depth, a grandeur of subdued sadness and quiet intelligence, which Dexter, for all his puffing and panting, could never imbue the windbag snob Morse with.

I say that Smiley belongs in the Cold World, but that isn't quite right. Smiley, rather, is always drawn back into the Cold World; it's the place of work which he ostensibly abjures, which he officially wants to be free from, but where he actually spends most of his life. It's there he confronts his enemies and near-doppelgangers, those who "are nothing", and who therefore dwell forever in the half-life of the Cold World: later, this will be Bill Haydon and Karla, but in A Murder Of Quality it is the compromised master Fielding. Smiley: always retiring, always drawn back into the permafrost from his lifeworld - which in any case is cold enough, with the very visible absence of Lady Ann, ("Ann isn't living here at the moment"), the Guinevere to his always-ailing Arthur, the constant cuckold's-horn sign of his lack. For Smiley, evidently, the Cold World is usually the no-man's land of the Cold War (le Carré will return to the Cold War in his next novel, the one that will prove to be his breakthrough, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold), and the disappearance of the Cold War background is one of the "oddnesses" - a word that is repeated in the novel - of A Murder Of Quality. The school, as you'd expect of such claustrophobic cloisters, is actually a rather overheated place, with le Carré offering a bitter take on the late-Fifties class condescencions and resentments. Yet amidst all this passion and anger there is the cold discontent of Fielding, and it is in his outbursts (against the futility of reproducing the mediocrity of the ruling class, for instance) that the Radio 4 play achieved its moments of greatest vividness, existential maladptation darkly flaring against the creaking whodunnit scenery. Dysphoria, I'm inclined to think, is le Carré's real subject. Note the slide, in the quotation above, from first-person identification - "there are some of us"- to third-person disavowal - "they are ashamed and frightened that they can't feel". Unlike Fielding, Smiley is no dysphoric by (un)natural inclination, but dysphoria is an occupational hazard to which he - so labile, so chameon-like, so at home in the zone where no-one warm and full can be at home - is far from immune.

Posted by mark at June 6, 2009 12:45 PM | TrackBack