November 29, 2007

I put my finger on the weird...

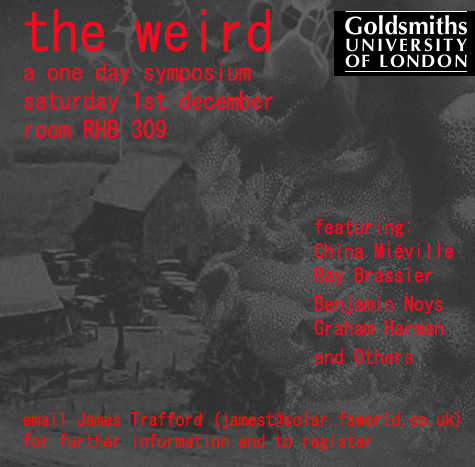

A reminder that the Weird event is taking place on Saturday at Goldsmiths. It's free of charge so if you around in London this week, please come along. The event is not intended for philosophy specialists, and will be centred on discussion rather than the delivery of papers. The speakers, all of whom have written and theorized about the Weird for a number of years, come from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives. New additions to the bill include Dean Kenning, the artist responsible for the recent 'The Dulwich Horror- H.P. Lovecraft and the Crisis in British Housing' exhibition, and Andy Sharp of English Heretic. The event is scheduled to start at noon. The text below will serve as the basis for my presentation.

The Door in the Wall: The Weird, worlds and the worldly

What follows is a reading of Wells’ extraordinary short story ‘The Door in the Wall’ (1911). It’s my conjecture that this story exemplifies a number of the defining features of the Weird, which I will seek to analyse and enumerate below.

‘The Door in the Wall’ is of particular interest because it is differs in several significant respects from Lovecraft’s tales. This is important, since any coherent and useable concept of the Weird must be applicable to more than the works of Lovecraft. Comparing Lovecraft’s stories to other examples of the Weird will allow us to begin to distinguish general properties of the Weird from particular techniques used by Lovecraft.

The most obvious point of departure from the formula of the Lovecraftian tale is the lack of any inhuman entities in ‘The Door in the Wall’. When Wallace passes through the door, he encounters strange beings, but they appear to be human. The feeling of the Weird that the story gives rise to is clearly not primarily produced by these languid, beneficent beings; and I want to argue further that the Weird does not require any of the ‘abominable monstrosities’ which are so central to Lovecraft’s tales.

The second way in which ‘The Door in the Wall’ deviates from the Lovecraftian model is the question of ontological hesitation. At the end of ‘The Door in the Wall’, Wells’ narrator, Redmond, finds his mind ‘darkened with questions and riddles’. He cannot dismiss the possibility that Wallace was suffering from an ‘unprecedented type of hallucination’. It is likely that Todorov would treat Wells’ story as a classic example of the Fantastic, since, at first glance, ‘The Door in the Wall’ seems to be poised in a state of unresolved tension between the Marvellous (the supernatural) and the Uncanny (in which the apparently supernatural is explained naturalistically). At the climax of a Lovecraft tale, by contrast, we can be sure that the Other world which the characters have encountered is real.

This leads to a third difference, which might possibly be subsumed into the second: the question of insanity. In Lovecraft’s tales, any insanity the characters experience is a consequence of the transcendental shock that the encounter produces; there is no question of the insanity causing characters to perceive the entities (whose status would then, evidently, be degraded; they would merely be products of a delirium). ‘The Door in the Wall’ leaves open the question of psychosis: it is possible – though Redmond doubts it, it is not his ‘profoundest belief’ – that Wallace is mad, or is deluded, or has confabulated the whole experience from garbled childhood memories (which, to use a distinction from Freud’s essay on ‘Screen Memory’ would then be memories of childhood, not memories from childhood). Wallace himself suspects that he may have augmented a childhood memory – re-dreamed it – to the point of completely distorting it. "I dreamt often of the garden. I may have added to it, I may have changed it; I do not know . . . . . All this you understand is an attempt to reconstruct from fragmentary memories a very early experience. Between that and the other consecutive memories of my boyhood there is a gulf. A time came when it seemed impossible I should ever speak of that wonder glimpse again."

With ‘The Door in the Wall’, the ontological question is not so much about the reality or not of the supernatural – there is nothing to suggest that the world behind the wall is ‘supernatural’, though it is certainly ‘enchanted’ - but about the opposition between the quotidian and the numinous. Wallace’s description of an ‘indescribable quality of translucent unreality, [different] from the common things of experience that hung about it all’ recalls Otto’s characterisation of the numinous in The Idea of the Holy. Yet, for both Wallace and Otto, an ‘indescribable quality of translucent unreality’ precisely accompanies encounters with that which is more real than ‘the common things of experience’. ‘To [Wallace] at least the Door in the Wall was a real door leading through a real wall to immortal realities.’

I wrote above that ‘The Door in the Wall’ turns on an ontological hesitation. This is misleading. In fact, ‘The Door in the Wall’ hesitates between an ontological resolution, in which Wallace really has made contact with an Other world, and an epistemological resolution, in which Wallace is suffering from some kind of delusion. Wallace is either a madman or a ‘dreamer, a man of vision and the imagination’. ‘We see our world fair and common,’ Redmond concludes, inconclusively, ‘the hoarding and the pit. By our daylight standard he walked out of security into darkness, danger and death. But did he see like that?’

Thresholds

It is this question of Worlds – and of contact between worlds – that I want to argue is central to the Weird. Weird fiction presents us with a threshold between worlds. ‘The Door in the Wall’ is, evidently, about just such a threshold. Much of its power derives from the opposition between the mundanity of the London setting, with its minutely delineated quotidiana - ‘he recalls a number of mean, dirty shops, and particularly that of a plumber and decorator, with a dusty disorder of earthenware pipes, sheet lead ball taps, pattern books of wall paper, and tins of enamel’ – and the ‘secret and peculiar passage of escape into another and altogether more beautiful world’.

Lovecraft’s stories are full of thresholds between worlds: often the egress will be a book (the dread Necromonicon), sometimes, as in the case of the Randolph Carter ‘Silver Key’ stories, it is literally a portal. Gateways and portals routinely feature in the deeply Lovecraftian stories of the Marvel comics character Doctor Strange. David Lynch’s film and television work is similarly fixated on doorways, curtains and gateways: Inland Empire appears to be a ‘holey space’ constructed out of thresholds between worlds, an ontological rabbit warren. Sometimes the threshold may only be a matter of re-scaling: Matheson’s The Incredible Shrinking Man demonstrates that your own living room can be a space of Weird wonder and dread if you become sufficiently small.

Between worlds

The notion of the between is crucial to the Weird. It is clear that if Wells’ story had taken place only in the Garden behind the wall, then no Weird charge would have been produced. In that situation, we would be in the realm of Fantasy (by which I obviously do not mean Todorov’s ‘Fantastic’, but ‘Fantasy’ in the sense that is used in contemporary fiction publishing). This mode of Fantasy naturalises OtherWorlds. But the Weird de-naturalises all worlds, in part by always prompting the question: what is a world? (this ontological estrangement-effect may be its most important political effect).

The Weird tale presents an Ontological montage in which a world – usually ‘our’ world, the world captured by naturalistic description and governed by commonsense – is ruptured or interrupted by what does not belong to it: that which is ‘out of space’, and/ or ‘out of time’. Lovecraft’s major breakthrough was perhaps his setting of his stories in a familiar New England setting (his earliest stories had taken place in a heightened Dunsanian OtherWorld). Similarly, Ramsey Campbell began by imitating Lovecraft, but his fiction only achieved a Weird effect when he started to set it in a naturalistic Liverpool. Ligotti’s most successful fiction, Crampton, is so powerful because its Weird involutions of time and space, its ontological haemorrhages, take place in a well-drawn naturalistic setting.

Graham Harman parallels the effect of ‘unvisualisability’ in Lovecraft’s text with the techniques of cubism; but the Weird also has a strong affinity with the textural discrepancies of collage. The Weird does not airbrush or photoshop incommensurable elements into a seamless CGI simulation; rather it insists upon, and consists in, the very incommensurability. That is why Julian House’s Lovecraft-inspired collages (see immediately below) are such apposite illustrations for the Weird.

Beyond the worldly

The Weird always expresses a dis-satisfaction with the worldly, the mundane. That is one way in which the Weird can be said to differ from Horror. There is certainly a crossover of the Weird and Horror – in many ways, Lovecraft is that crossover – but the Things of the Weird are never merely horrible or terrifying. If they elicit a shudder, it is not merely a shudder of fear, but a shudder of ontological unease that typically contains a thrill of wonder, a vertiginous delight that there is something beyond the mean confines of the mundane. It is clear, for example, that no matter how many negative adjectives Lovecraft piles onto his abominable entities, they are objects of wonder as much as dread.

The attack on the deficiencies of the worldly is of course explicit in ‘The Door in the Wall’. "Oh! the wretchedness of that return!" Redmond complains, when he finds himself back in ‘this grey world again’. Redmond attributes his ‘quite ungovernable grief’ to a failure of fidelity to the Weird.

- "Well", he said and sighed, "I have served that career. I have done--much work, much hard work. But I have dreamt of the enchanted garden a thousand dreams, and seen its door, or at least glimpsed its door, four times since then. Yes--four times. For a while this world was so bright and interesting, seemed so full of meaning and opportunity that the half-effaced charm of the garden was by comparison gentle and remote. Who wants to pat panthers on the way to dinner with pretty women and distinguished men?”

Wallace feels that he is depressed – ‘the keen brightness that makes effort easy has gone out of things recently’ - because he has yielded to the temptations of the worldly, failed to keep faith with ‘the haunting memory of a beauty and a happiness that filled his heart with insatiable longings that made all the interests and spectacle of worldly life seem dull and tedious and vain to him’.

- "Here I am!" he repeated, "and my chance has gone from me. Three times in one year the door has been offered me--the door that goes into peace, into delight, into a beauty beyond dreaming, a kindness no man on earth can know.”

Thus Wallace finds himself – adopting for a moment the perspective of a worldliness he has now almost entirely rejected - “grieving--sometimes near audibly lamenting--for a door, for a garden!"

The Weird and Psychoanalysis

When Wallace describes his grief, he seems to be a plaything of our old friend, the death drive. "The fact is--it isn't a case of ghosts or apparitions--but--it's an odd thing to tell of, --I am haunted. I am haunted by something--that rather takes the light out of things, that fills me with longings . . . . ." The pull exerted by the door and the garden deprives all of his worldly satisfactions and achievements of their flavour.

- Now that I have the clue to it, the thing seems written visibly in his face. I have a photograph in which that look of detachment has been caught and intensified. It reminds me of what a woman once said of him--a woman who had loved him greatly. "Suddenly," she said, "the interest goes out of him. He forgets you. He doesn't care a rap for you--under his very nose . . . . ."

The door was far from the start an ambivalent object, a threshold leading beyond the pleasure principle: ‘he did at the very first sight of that door experience a peculiar emotion, an attraction, a desire to get to the door and open it and walk in’. Redmond then imagines ‘the figure of that little boy, drawn and repelled’ (emphasis added).

Is there something inherently Weird about the death drive? There are grounds for saying that the greatest of all fictions about the death drive – Melville’s Moby Dick – is a vastly distended Weird Tale. ‘“What is it,” asks Ahab,

- what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozzening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is Ahab, Ahab?”

Psychoanalysis, whose object of study and treatment is those ‘nameless, inscrutable, unearthly things’ that go ‘against all natural lovings and longings’, can be – and usually is - placed under the sign of the Uncanny. Freud’s great essay on ‘The Uncanny’ – with all its ambivalences, its repetitions, its over-hasty closures – remains the most potent theorization of the uncanny. The domain of psychoanalysis can be seen as the place of the unheimlich or the unhomely, the estranged familiar/ familial. But can’t the unconscious also be considered Weird, with psychoanalysis the threshold into its alien world? Is Lacanianism – which drew upon the same Surrealist and Modernist collage-art which fascinated and repelled Lovecraft – the revenge of the Weird upon Freud’s tendency towards homeliness? Certainly, ‘The Door in the Wall’ seems to belong to a ‘Lacanian Weird’ but is the Weird inherently Lacanian, or is Lacanianism just one mode of the Weird?

November 25, 2007

Marxist Supernanny

|  |

(‘Marxist Supernanny’ was a phrase Dejan used in respect of the dear departed Little Lord Lack, who in the end was neither a Marxist or a Supernanny, although he no doubt had a Nanny or two.)

Nothing could be a clearer illustration of the famous failure of the Father function, the crisis of the paternal superego in late capitalism, than a typical edition of Supernanny. The programme offers what amounts to a relentless, although of course implicit, attack on postmodernity’s permissive hedonism. Supernanny is a Spinozist insofar as she takes it for granted that children are in a state of abjection. They are unable to recognise their own interests, unable to apprehend either the causes of their actions or their (usually deleterious) effects. But the problems that Supernanny confronts do not arise from the actions or character of the children – who can only be expected to be idiotic hedonists – but with the parents. It is the parents’ following of the trajectory of the pleasure principle, the path of least resistance, that causes most of the misery in the families. In a pattern that quickly becomes familiar, the parents’ pursuit of the easy life leads them to accede to their children’s every demand, which become increasingly tyrannical.

Rather like many teachers or other workers in what used to be called ‘public service’, Supernanny has to sort out problems of socialization that the family can no longer resolve. A Marxist Supernanny would of course turn away from the troubleshooting of individual families to look at the structural causes which produce the same repeated effect.

The problem is that late capitalism insists and relies upon the very equation of desire with interests that parenting used to based on rejecting. In a culture in which the ‘paternal’ concept of duty has been subsumed into the ‘maternal’ imperative to enjoy, it can seem that the parent is failing in their duty if they in any way impede their children’s absolute right to enjoyment. Partly this is an effect of the increasing requirement that both parents work; in these conditions, when the parent sees the child very little, the tendency will often be to refuse to occupy the ‘oppressive’ function of telling the child what to do. The parental disavowal of this role of is doubled at the level of cultural production by the refusal of 'gatekeepers' to do anything but give audiences what they already (appear to) want. The concrete question is: if a return to the paternal superego - the stern father in the home, Reithian superciliousness in broadcasting - is neither possible nor desirable, then how are we to move beyond the culture of monotonous moribund conformity that results from a refusal to challenge or educate? A question as massive as this cannot of course be answered in one post, and what follows here will require a great deal of further elaboration. In brief, though, I believe that it is Spinoza who offers the best resources for thinking through what a 'paternalism without the father' might look like.

In Tarrying with the Negative, Zizek famously argues that a certain Spinozism is the ideology of late capitalism. Zizek believes that Spinoza’s rejection of deontology for an ethics based around the concept of health is allegedly flat with capitalism’s amoral affective engineering. The famous example here is Spinoza’s reading of the myth of the Fall and the foundation of Law. On Spinoza’s account, God does not condemn Adam for eating the apple because the action is wrong; he tells him that he should not consume the apple because it will poison him. For Zizek, this dramatizes the termination of the Father function. An act is wrong not because Daddy says so; Daddy only says it is ‘wrong’ because performing the act will be harmful to us. In Zizek’s view, Spinoza’s move both deprives the grounding of Law in a sadistic act of scission (the cruel cut of castration), at the same time as it denies the ungrounded positing of agency in an act of pure volition, in which the subject assumes responsibility for everything.

In fact, it is Spinoza has immense resources for analysing the affective regime of late capitalism: its dissolving of agency in a phantasmagoric haze of psychic and physical intoxicants, its blitzing of the nervous system with images. (Spinoza remains the pre-eminent philosopher of image addiction). It is precisely Spinoza’s avoiding of the heroic Oedipal dramaturgy to which Zizek is so attached that enables him to give a plausible account of how responsibility can be attained rather than assumed. Spinoza’s diagnosing of the Father-God of theism as an anthropomorphic fantasy anticipates the psychoanalytic insight that the infant phantasmatically posits a castrating Father figure in order to cover over the impossibility of total enjoyment (‘If it were not for him, I’d have everything I want’). (And far from being the One hallucinated by Hegelian dementia, the Spinozist God is better understood as a desolated Zero. ‘The true formula of atheism is that God is unconscious,’ Lacan declares; and Spinoza’s God is exactly that: not a distributed, pantheistic omnipresence, but the cosmos as catatonic mechanism.) The most important difference between Spinoza and Lacan does indeed concern the question of pathology. If Spinoza aims to cure the individual of their addictions and fixations, Lacan believes that they can only be managed or sublimated. Spinozist joy consists in a calm contemplation of the impersonal mechanism of the cosmos, including your self; very different from Lacanian jouissance. But the idea that pathology can only ever be sublimated, never eliminated, that the subject can only ever circulate around objects that will never satisfy it, but which it can never give up pursuing – is, if not the ideology of late capitalism, then its metapyschology.

Late capitalism certainly articulates many of its injunctions via an appeal to (a certain version of) health. The banning of smoking in public places, the relentless monstering of working class diet on programmes like ‘You Are What You Eat’, do appear to indicate that we are already in the presence of a paternalism without the Father. It is not that smoking is ‘wrong’, it is that it will lead to our failing to lead long and enjoyable lives. But there are limits to this emphasis on good health: mental health and intellectual development barely feature at all, for instance. (When will there be a Channel 4 programme called ‘You Are What You Read?’) What we see instead is a reductive, hedonic model of health which is all about ‘feeling good’. To tell people how to lose weight, or how to better decorate their neo-liberal burrow, is acceptable; but to call for any kind of cultural improvement is to be oppressive and elitist. The alleged elitism and oppression cannot consist in the notion that a third party might know someone’s interest better than they know it themselves, since, presumably smokers, or those hectored by coprophiliac crank Gillian McKeith are deemed either to be unaware of their interests or incapable of acting in accordance with them. No: the problem is that only certain types of interest are deemed relevant, since they reflect values that are held to be consensual. Losing weight, decorating your house and improving your appearance belong to the 'consentimental' regime of what Adam Curtis calls the ‘empire of the self’. In an excellent interview – which I’m indebted to reader Daryl Hutchings for drawing to my attention to – Curtis berates the way in which contemporary media is increasingly a machinery that is organised around the manipulation of affect.

- TV now tells you what to feel.

It doesn't tell you what to think anymore. From EastEnders to reality format shows, you're on the emotional journey of people - and through the editing, it gently suggests to you what is the agreed form of feeling. "Hugs and Kisses", I call it.

I nicked that off Mark Ravenhill who wrote a very good piece which said that if you analyse television now it's a system of guidance - it tells you who is having the Bad Feelings and who is having the Good Feelings. And the person who is having the Bad Feelings is redeemed through a "hugs and kisses" moment at the end. It really is a system not of moral guidance, but of emotional guidance.

Morality has been replaced by feeling.

In the ‘empire of the self’ everyone ‘feels the same’ without ever escaping a condition of solipsism. ‘What people suffer from,’ Curtis claims,

- is being trapped within themselves - in a world of individualism everyone is trapped within their own feelings, trapped within their own imaginations. Our job as public service broadcasters is to take people beyond the limits of their own self, and until we do that we will carry on declining.

The BBC should realise that. I have an idealistic view, but if the BBC could do that, taking people beyond their own selves, it will renew itself in a way that jumps over the competition. The competition is obsessed by serving people in their little selves. And in a way, actually, Murdoch for all his power, is trapped by the self. That's his job, to feed the self.

In the BBC, it's the next step forward. It doesn't mean we go back to the 1950s and tell people how to dress, what we do is say "we can free you from yourself" - and people would love it.

Curtis attacks the internet because, in his view, it facilitates communities of solipsists, interpassive networks of like-minds who confirm, rather than challenge, each other’s assumptions and prejudices. Instead of having to confront other points of view in a contested public space, these communities retreat into closed circuits. But, Curtis claims, the impact of internet lobbies on Old Media is disastrous, since, not only does its reactive pro-activity allow the media class to further abnegate its function to educate and lead, it also allows populist currents on both the Left and the Right to ‘bully’ media producers into turning out increasingly mediocre and anodyne programming.

Needless to say, I think that Curtis’s critique has a point, but it misses important dimensions of what is happening on the net. One of the reasons that I dropped comments boxes was that they started to act as a form of censorship; I became increasingly aware that posts were being warped by anticipation of what some commenters, seldom the most interesting commenters either, might say. Luke Heronbone was ridiculed for saying that comments boxes are ‘too nice’ but this captures a dimension of what is so insidious about them. The tendency in comments boxes and discussion boards is for them to more closely resemble banal sociality – in both its qualities of vacuous convivalitity and boorish aggression – than writing. A kind of commonsense politesse (and its other: personalized antagonism) descends, in which the de-personalising effect of writing is replaced by the comforting role of ‘being a person’, a face, again. I write precisely because it is the most effective way I know of ‘getting out of my face’. (I note the irony of illustrating this piece with faces; faciality is certainly worth a post of its own.) In spite of what postmodernity’s ubiquitious biographism would have us believe, writing allows one to escape one’s personal history: Spinoza (and Althusser, who followed him very closely in this respect) understood that freedom is only possible once we begin to apprehend the structural determinations that engender our illusion of being naturally autonomous subjects. Spinozist joy arises from a slow, careful dismantling of the self – not a temporary obliteration of the self by the use of intoxicants, but a sober, cognitive detachment from the sad passions that once agitated us.

Contrary to Curtis’ account of blogging, though, blogs can generate new networks that have no correlate in the social field outside cyberspace. One of the most interesting aspects of this site for me is the way that it has produced its own audience rather than appealed to an already existing demographic. Ask yourself this: where else could you now encounter a piece like the one you are currently reading except in cyberspace? As Old Media increasingly becomes subsumed into PR, and the consumer report replaces the critical essay, some zones of cyberpsace offer pretty much the only resistance to an otherwise dominant ‘critical compression’.

|  |

As Christian Marazzi, Richard Sennett and others have argued, the success of neoliberalism is based on its capturing of working class desires. It was Fordist workers who dreamt of a world less monotonous and predictable, who wanted to own their own homes and have wrest control of own lives from State bureaucracies. Neoliberalism successfully caricatured the Left as the lobby preventing this, the party committed to the Nanny State and its attendant sclerotic and scleroticising bureaucracy. The problem was that the Left fell into the trap, by seeing their dilemma as a choice between ‘sticking to their guns’ and calling for the return of State centralization, or by demonstrating how ‘flexible’ they could be by adopting neo-liberalism wholesale. The development of New Labour is of course the sorry story of how the latter option was pursued. In Brown’s terrifyingly comprehemsive restructuring of himself, of his self - his ‘re-engineering of his soul’ from Presbyterian Socialist to glowering Sinthommosexual to non-paternalist Father of the Nation - we can see the parliamentary Left’s capitulation to neo-liberalism played out in the psyche of one market Stalinist (a gruesome subject that’s well worth a post in itself).

It’s now time – well past time, actually – for the Left to finally disarticulate itself from the big State. Zizek’s piece in the current LRB reiterates his opposition to Badiou’s notion of ‘distance from the State’. But being ‘at a distance from the State’ does not mean either abandoning the State or retreating into the private space of affects and diversity which Zizek rightly argues is the perfect complement to neoliberalism’s domination of the State. It means recognizing that the goal of a genuinely new Left should be not be to take over the State but to subordinate the State to the general will. This involves, naturally, resuscitating the very concept of a general will, reviving – and modernising - the idea of a public space that is not reducible to an aggregation of individuals and their interests. The ‘methodological individualism’ of the neoliberal worldview presupposes the philosophy of Max Stirner as much as that of Adam Smith or Hayek in that it regards notions such as the public as ‘spooks’, phantom abstractions devoid of content. All that is real is the individual (and their families).

The symptoms of the failures of this worldview are everywhere – in a disintegrated social sphere in which teenagers shooting each other has become commonplace, in which mental illness and affective disorders of every kind are proliferating at an alarming degree, in which hospitals incubate aggessive Superbugs - what is required is connect effect to structural cause. Far from being isolated, contingent problems, these are all the effects of a single systemic cause: Capital.

Zizek argues that, now, it is the likes of Microsoft which resist State power, but he fails to draw the lesson from this. Like neoliberalism in general, Microsoft has achieved its global domination not so much by occupying the State as by subordinating the machinery of government to its interests. Far from nationalising Microsoft, as Zizek once called for, the Left should hold up Microsoft as the most spectacular example of the way in which capitalist products and companies are at least as shoddy as those turned out by the nationalised industries that neoliberalism has spent three decades demonising. Microsoft’s domination of the market to the point where market conditions no longer obtain, its ability to foist on its customers inferior products that they only buy because everyone else already has them, could not be further from the neoliberal fantasy of the market as an intelligent mechanism super-sensitive to consumer desire. But, far from being an exceptional case, Microsoft is typical of SF Capital’s anti-market.

It is by now clear that neoliberalism does not provide the conditions for a vibrant culture. Exactly to the contrary in fact. As Curtis argues, the interpassive simulation of participation in postmodern media, the network narcissism of MySpace and Facebook, generates content that is repetitive, parasitic and conformist. Ironically, the media class’s refusal to be paternalistic has not produced a bottom-up culture of breathtaking diversity, but one that is increasingly infantalized. The effect of permanent structural instability, the ‘cancellation of the long term’, is invariably stagnation and conservatism rather than innovation. This is not a paradox. As Adam Curtis’ remarks above make clear, the affects that predominate in late capitalism are fear and cynicism. These emotions do not inspire bold thinking or entrepraneurial leaps, they breed conformity and the cult of the minimal variation, the turning out of products which very closely resemble those that are already successful. Meanwhile, films such as Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Stalker - plundered by Hollywood since as far back as Alien and Blade Runner - were produced in the ostensibly moribund conditions of the Brezhnevite State, meaning that the USSR acted as a cultural entrepreneur for SF Capital.

The Left should argue that it can deliver what neoliberalism has signally failed to do: a massive reduction of bureaucracy, a handing back of control of work and life from rhizomaniac bureaucracies to workers. As Deleuze demonstrated in his essay on Control – whose prescience becomes all the more startling the deeper we sink into late capitalism – post-Fordist capital would not eliminate bureaucracy but alter its form. Bureaucracy is no longer the preserve of a centralised State; it has proliferated into a generalised condition of surveillance-without-a-centre performed by distributed para-State bodies or micro-States which increasingly co-opt the so-called individual into doing their work for them. Far from being some aberration that capitalism’s alleged efficiency will eventually eliminate, late capitalist ‘administration’ is a permanent and ineradicable feature of late capitalism. There is no more prospect of administration receding than there was of the Stalinist State ever decreeing its own withering away.

Zizek’s invocation of Chavez in his LRB piece is typical of a nostalgia for the Father – the stern but good Lawgiver who leads his people into the Promised Land by a heroic act of resistance to the global order - that characterises his own work (the ostensibly playful defence of Stalinism is a part of this) and which continues to hold the Left in general back. The Left needs to give up its belief in Fathers, Good and Bad. We all know that Bush is a puppet not a papa, but political strategy needs to reflect this, by no longer appealing to him – or any other Bad Father figure - as if they were capable of granting its wishes. A mature, rational anti-capitalist politics needs to be able to think beyond the phantasms of the family, to imagine an abstract public space not embodied in the figure of a facialized individual.

November 21, 2007

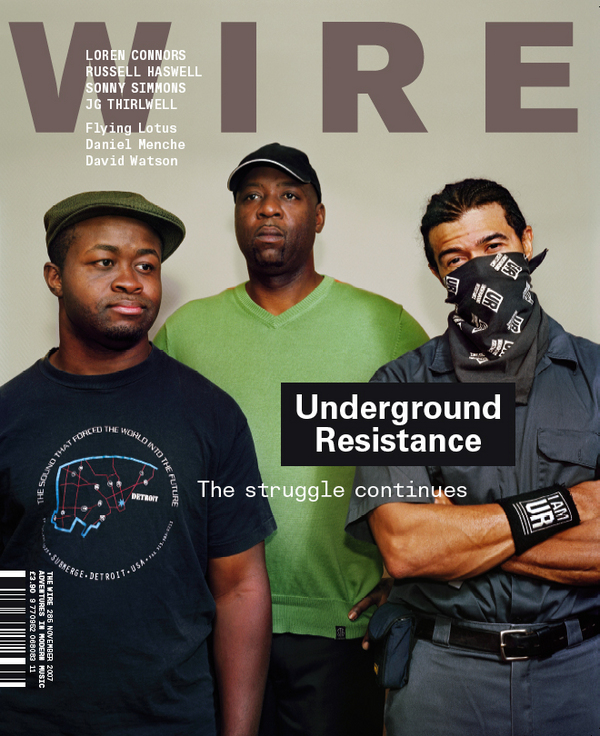

Is it really you that's making the track?

- As a keyboard player, or guitar player, or bass player, I'm decent at what I do, but there's times when people in church get into it, and the feeling comes, and the spirit comes, and you can play way beyond your ability. In fact, you know the bass pedal on the organ? I always have trouble with it. I have to look down and play the bass, it's difficult but when the spirit comes you don't have to look down, your foot be moving, so at the point you realise that I ain't really playing this organ. So it's the same with a track. If the spirit come when you make a track, the question then becomes 'Is it really you making the track?'

From the unedited transcript of my interview with Mike Banks , now up on the Wire website...

November 08, 2007

November 05, 2007

Historical Materialism Annual Conference

Fourth Historical Materialism Annual Conference 9–11 November 2007 at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, WC1

In association with Socialist Register and the Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize Committee

Full Programme available here.

Online bookings deadline is 12.00 pm on Thursday, 8 November !

The annual Historical Materialism conference is organised by the editorial board of Historical Materialism in association with the Deutscher Memorial Prize committee and the Socialist Register. The conference has become an important event on the Left, providing an annual forum to discuss recent developments on the agenda of historical-materialist research and has attracted an increasingly high attendance over the past three years.

While there is no call for papers this year, the Editorial Board of Historical Materialism welcomes attendance and active engagement in discussion with panellists from new as well as prior participants with an interest in critical-Marxist thought. One of the principle objectives of the conference has been to build bridges among the various Marxist communities, including the breaking down some of the linguistic and intellectual barriers which continue to hamper the circulation and expansion of critical-Marxist thought. The fourth annual Historical Materialism Conference promises to continue and take forward this objective.

The conference is organised around three plenary sessions (the Deutscher lecture, the launch of the Socialist Register 2008, and Historical Materialism’s plenaries) as well as workshops dedicated to specific themes. Some of the themes for the panels include: the labour process, neoliberalism and class, cinema (including film screenings), Gramsci, finance, utopia, Israel & Palestine, political economy, the 90th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, social movements, materialism & philosophy, world development, art & politics, slavery, Marx’s Grundrisse, postcolonialism, Islam and the American Empire, value theory, Debord and the society of the spectacle.

Confirmed speakers include:

Bashir Abu-Manneh, Gilbert Achcar, Christine Achinger, Brian Alleyne, Sabah Alnasseri, Christopher J. Arthur, Sam Ashman, Maurizio Atzeni, Sedat Aybar, Sarah Badcock, Giorgio Barratta, Luca Basso, Asef Bayat, Jonathan Beller, Riccardo Bellofiore, Ana Cecilia Bergene, Henry Bernstein, Andreas Bieler, Sophie Béroud, Jacques Bidet, Robin Blackburn, Chris Bolsmann, Paola Bonifazio, Derek Boothman, Atilio Boron, Mark Bould, Stephen Bouquin, Robert Brenner, Andrew Brown, Tom Bunyard, Ray Bush, Alex Callinicos, Paul Cammack, Liam Campling, Gavin Capps, Giuseppe Caruso, John Chalcraft, Lorenzo Chiesa, Andrew Chitty, Simon Clarke, Alex Colas, Gareth Dale, Neil Davidson, Gail Day, Tim Dayton, Massimo de Angelis, Radhika Desai, Ana Dinerstein, Paolo dos Santos, Antoni Domenech, Albert Domingo, Fernando Duran, Andy Durgan, Steve Edwards, Tony Elger, Ferdan Ergut, Mauro Farnesi, Ben Fine, Roberto Fineschi, Carl Freedman, Alan Freeman, Gregor Gall, Heide Gerstenberger, Melanie Gilligan, Andrew Glyn, Hugh Goodacre, Jonathan Goodhand, Jamie Gough, Peter Gowan, Volker Gransow, Diego Guerrero, Peter Hallward, Jane Hardy, Chris Harman, Graham Harrison, Barbara Harriss-White, David Harvie, Owen Hatherley, Micheal Head, Michael Heinrich, Renate Holub, Richard Hyman, Makoto Itoh, Peter Ives, Donna Jones, Patrick Keiller, John Kelly, Mick Kennedy, Laleh Khalili, Jim Kincaid, Jeff Kinkle, Gal Kirn, Sharon Kivland, Sam Knafo, Onur Suzan Komurcu, Michael Kraetke, John Kraniauskas, Hannes Lacher, Rocco Lacorte, Mark Laffey, Spiros Lapatsioras, Costas Lapavitsas, Ching Kwan Lee, Esther Leslie, William Lewis, Renzo Llorente, Dic Lo, Giacomo Marramao, David McNally, George Meramveliotakis, Alessandra Mezzadri, Keir Milburn, John Milios, Owen Miller, Toby Miller, Dimitris Milonakis, Kim Moody, Fred Moseley, Rastko Mocnik, Simon Mohun, Adam Morton, Kevin Murphy, Mike Neary, Michael Neocosmos, Paolo Novak, Benjamin Noys, Carlos Oya, Bryan Palmer, Silke Panse, Ilan Pappé, Anna Pollert, Nina Power, Ozren Pupovac, Devi Sacchetto, Mõkkel Bol Rasmussen, Christopher Read, Mike Richards, Glenn Rikowski, Spyros Sakellaropoulos, Jyoti Saraswati, Hajime Sato, Ben Selwyn, Helena Sheehan, Stuart Shields, Subir Sinha, Bev Skeggs, John Smith, Tony Smith, Panagiotis Sotiris, Benno Teschke, Adrien Thomas, Peter Thomas, Massimilano Tomba, Alberto Toscano, Greg Tuck, Vanessa Ushie,Kees van der Pijl, Elisa van Waeyenberge, Fabio Vighi, Mike Wayne, Tunde Zack Williams, Paul Willis, Jane Wills, Frieder Otto Wolf, Tony Wood, Owen Worth, Leo Zelig, Slavoj Zizek.

Attendance is free. However, the conference is entirely self-financed and we will depend on voluntary donations by attendants and participants to support the event. The suggested advanced online donation is £30 for waged and £10 for unwaged

Sincerely,

The Editorial Board of Historical Materialism