December 24, 2007

Flat wildernesses

Orford Ness from Aldeburgh, December 2007

Aldeburgh, December 2007

'The place on the east coast which the reader is asked to consider is Seaburgh. It is not very different now from what I remember it to have been when I was a child. Marshes intersected by dykes to the south, recalling the early chapters of Great Expectations; flat fields to the north, merging into heath; heath, fir woods, and, above all, gorse, inland.'

Aldeburgh, December 2007

Cooling, Kent, yesterday

'Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea. My first most vivid and broad impression of the identity of things, seems to me to have been gained on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening.'

Cooling, Kent, yesterday

'At such a time I found out for certain, that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana wife of the above, were dead and buried; and that Alexander, Bartholomew, Abraham, Tobias, and Roger, infant children of the aforesaid, were also dead and buried; and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond, was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip.'

Cooling, Kent, yesterday

'To five little stone lozenges, each about a foot and a half long which were arranged in a neat row beside their grave, and were sacred to the memory of five little brothers of mine -- who gave up trying to get a living, exceedingly early in that universal struggle -- I am indebted for a belief I religiously entertained that they had all been born on their backs with their hands in their trousers- pockets, and had never taken them out in this state of existence.'

December 17, 2007

Weird/ Psychoanalysis

Heuristic England with a fascinating account of 'Le Délire de Négation', aka Cotard's syndrome. (It sounds like Judge Schreber might have suffered from this condition, in which sufferers often believe that they have no stomach and bowels.)

The Heuristic England post takes up one of the most interesting discussions at the recent symposium on The Weird, on the relation of negativity, the horrible and horror to the Weird. My position remains that there is no necessary relation between the Weird and Horror, which is not, evidently, to say that the Weird cannot be horrible, only that it need not be. The Weirdness of 'The Door in the Wall' does not arise from the 'horrible' elements of the story - Wallace's death and derangement - but from the 'out of placeness' of the garden in quotidian London, the incommensurability of the different worlds that Wallace travels between. I think it's quite possible to imagine a different version of 'The Door in the Wall', one in which Wallace's vision of the numinous was vindicated, without the tale losing its Weird charge.

- If you were to see written on a door panel: "This opens onto the void," wouldn't you still want to open it? - Baudrillard, Seduction

It strikes me that is it is not horror but fascination - albeit a fascination usually mixed with a certain trepidation, if not repulsion - that is integral to the Weird. I would argue, further, that if this element of fascination were entirely absent from a story, and if the story were merely horrible, it would no longer be Weird.

Fascination is the affect shared by Lovecraft's characters and his readers. Fear or terror are not shared in the same way. Lovecraft's characters are often terrified, but his readers seldom, if ever, are. It is fascination, above all else, that is the engine of fatality in Lovecraft's fictions, fascination that draws his bookish characters towards the dissolution, disintegration or degeneration that we, the readers, always foresee. This is the death drive not in the sense of an impulse towards homeostasis - as China rightly pointed out, and as Graham Harman's philosophy establishes, the Weird deprives us of the consoling idea of a final state of quiescence by showing that that there is no truly inanimate, that there is no end to the teeming (echoing Lacan, who according to Copjec, 'pictures the real as teeming with emptiness, as a swarming void'). The death drive in question is the drive which Zizek has so tirelessly described: an undeath drive that is not directed towards organic death but which persists in a state of zombie twitch immortality, indifferent to the end of the organism. That is why Ben is right to suggest that the rendezvous between Zizek and Lovecraft is a missed appointment. Yet for me this is not because Lovecraft is a pessimistic author, but because his writing fairly froths and foams with jouissance. 'Frothing', 'foaming', 'teeming', are themselves Lovecraftian words, of course, but they could apply equally well to the 'obscene jelly' of jouissance. This is not to make the absurd claim that there is no negativity in Lovecraft - the loathing and abomination are hardly concealed -, only that negativity does not have the last word. Lovecraft-the-symptom, in fact, is an exemplary demonstration of the advance that psychoanalysis makes over pessimsim. Freud remarks during Beyond the Pleasure Principle that 'we have unwittingly steered our course in the harbour of Schopenhauer's philosophy'. But what Freud establishes in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, surely, is that the enjoyment of what is supposedly negative, the taking of pleasure from what is ostensibly painful, wrecks any possibility of a total pessimism. An excessive preoccupation with objects that are 'officially' negative always indicates the work of jouissance - a mode of enjoyment which does not in any sense 'redeem' negativity: it sublimates it. That is to say, it transforms an ordinary object causing displeasure into a Thing which is both terrible and alluring, which can no longer be libidinally classified as either positive or negative. The Thing overwhelms, it cannot be contained, but it fascinates.

Ligotti's unknown pleasures

It was in the session that the relation between the Weird and negativity came into sharpest focus. Ligotti's texts are marked by a tension between his personal philosophy of total pessimism and his writing practice, which - perforce, performatively - contradicts the unremitting negativity of his official worldview. Since Ligotti recurrently suffers from anhedonia, the inability to take pleasure, in his texts, as James Burton astutely put it, it is pleasure that is the noumenal, the unknowable. But, rather like Beckett's Unnamable - the Lovecraftian echo here hardly need be stressed at this point - Ligotti finds that the sheer fact of writing mitigates his pessimism. It would be a mistake to read The Unmamable's 'I'll go on' redemptively, as the triumph of some indomitable spirit, human or otherwise. Beckett makes contact instead with an intensive negativity, a purgatorial continuum in which things can always get worse, without ever reaching the relief of the worst. Total negativity would yield quiescence, yet for Beckett, as for Ligotti, silence and stasis are unattainable, they lie outside texts which might be for nothing but which are not, cannot be, nothing. Those afflicted with being might yearn for nothingness, yet even their dreams belong to being.

The ontological haemorrhage to which Beckett's 'characters' in the Trilogy are subject - the collapsing of Molloy's world into the worlds of Malone, Macmann and the Unnnamable - is echoed in Ligotti by the repeated 'moment of consummate disaster, when the puppet turns to face the puppet master'. Just as 'the Unnamable not only imagines characters, he also tries to imagine himself as the character of someone else' (McHale) so Ligotti's marionettes begin to see 'themselves' as interiorless iterations in a purgatorial recursive structure which extends 'upwards' (towards an ostensible master who turns out to be a puppet) and 'downwards' (towards a puppet who leers at his supposed master) infinitely. This is a reverse Leibnizian hypercosmos, in which whatever world you are in, it is always the worst; where worlds, far from being incompossible, all end up bleeding into one another, as a kind of oozing ontological cancer consumes every possible world. Ligotti's is a version of Plantinga's transworld depravity, except the corruption belongs to Creation itself, and to any act of creation. To conjure something out of nothing is always unforgivable: because, once created, there is no way back out to non-being. This is a kind of Gnosticism without a demiurge, where every being is both a blind idiot god and a helpless puppet who only has the power to curse its creator. The horror of profound depression is not just the feelings of negativity, but the impossibility of living the negativity, the discrepancy between the dejection of one's affective condition and what Francis Bacon called the optimism of your nervous system. Having lost the will to live, you find that life does not require will - or at least, it does not need your will. Even when you feel that you are a living corpse, the organs possess a will of their own.

At this point, we have passed beyond the Weird. As Ray argued, Ligotti tries to pursue the Weird-as-such, a Weird in itself, a Weird entirely estranged from naturalism and any recognizable world. Yet Ligotti's stories in this mode become exercises in mannerism which lose the Weird. His Weirdest story - and his most successful in my view - is the eerie unmade screenplay Crampton in which all of Ligotti's motifs are inserted into an American landscape of cheap TV adverts and greasy small town cafes.

Sublimation and Weird Psychoanalysis

English Heretic's highly stimulating presentation gave me an answer to the question I had posed about psychoanalysis's relationship to the Weird. What is reactionary about psychoanalysis is intricately tied up with what is most radical about it, which is why Anti-Oedipusand The Century can both be right when they, respectively, attack Freud for his familialism and celebrate psychoanalysis for its denaturalization of the family structure. English Heretic looked at the etymological roots of the word 'weird' in the concept of the Wyrd as weaver of Fate. It was Shakespeare who introduced 'weird' into the English language in the Fate-driven story of Macbeth; and, in its hyperstitional structure, Macbeth interestingly echoes the story of Oedipus. In both, the prophecies generate the catastrophe; or, rather, the attempt to escape the prophecies makes them come true. The signs are themselves the engine of fatality. (See here for my previous discussion of the Oedipus myth as a closed loop paradox: 'one knows in advance one's destiny, one tries to evade it, and it is by means of this very attempt that the predicted destiny realizes itself.' [Sublime Object of Ideology .)

It is no accident - or rather, it is the kind of accident that it is necessary - that the Oedipus story should become so central to psychoanalysis, since it is precisely about the capturing of the Weird in a family drama. If Oedipus and Macbeth consitute a bad fatality, then English Heretic outlined the contours of an anti-Oedipal virtuous fatality, a kind of Dadaist sorcery which makes Fate out of a chance encounter. The aleatory systems of Dadaism provide the model for an account of sublimation which is not hampered - as Copjec argues that Freud's was - 'by the "epistemological obstacle" of [Freud's] conservative taste in art'. (This by contrast with Lacan, of course, who 'had a different understanding of art and a close association with the surrealist avant garde'.)

The central problem of Dada and Surrealism - the one that Duchamp kept returning to - was exactly the one that English Heretic laid out: the fatal twinning of chance and necessity. Its aleatory systems were not just machines that would produce random effects, but, far more importantly, systems that would transform a 'chance encounter' into a necessity. Dada and Surrealist practice can be seen precisely as a Weird psychoanalysis, which, instead of shooing away strange animals, or looking for the roots of aberrant machines in family relations, cultivated a positive psychopathology from bizarre juxtapositions in experience. Witness one of EH's examples, Max Ernst:

- One of his best friends, a most intelligent and affectionate pink cockatoo, died in the night of January 5th. It was an awful shock to Max when he found the corpse in the morning and when, at the same moment, his father announced to him the birth of his sister Loni. The perturbation of the youth was so enormous that he fainted. In his imagination he connected both events and charged the baby with the extinction of the bird's life. A series of mystical crises, fits of hysteria, exaltations and depressions followed. A dangerous confusion between birds and humans became encrusted in his mind and asserted itself in his drawings and paintings (1906-1914). Excursions in the world of marvels, chimeras, phantoms, powers, monsters, philosophers, birds, women, lunatics, magi, trees, eroticism, stones, insects, mountains, poisons, mathematics and so on.(1924). (from Nadia Choucha, Surrealism & The Occult)

Ben has described how the object of horror in Lovecraft is often this 'surrealist avant garde' itself. But, in making the avant garde so central - and what could be more central to Lovecraft than his official object of loathing? - Lovecraft's 'reactionary modernism' was constitutively unable to abject the avant garde, and became instead fatally infected with it, implicated in it.

Lacan, on the other hand, is a kind of aggravated or ultra-modernist whose style and theory could be seen as the result of the subjecting one modernism - Freud's psychoanalysis - to the techniques of another (Dada/ Surrealism). Ballard performs a similar operation; although he does so, not with the rarefied materials of high modernism, but as a pulp modernist who montages Dada into the media landscape; or, better, he sees the ways in which the media landscape was already Dadaist. And what is Deleuze-Guattari's schizoanalysis if not a psychoanalysis given over to the Weird? A Thousand Plateaus, with its repeated references to Lovecraft, Moby Dick and The Incredible Shrinking Man, is in part a book of the American Weird. And Baudrillard, the great reader of Ballard and P K Dick, wasn't he, too, fascinated by the Weird (as well as being one of the greatest theorists of the fatal pull of fascination)?

- That which looks onto nothing has every reason to be opened. ... That which is arbitrary is simultaneously endowed with a total necessity. The predestination of the empty sign, the precession of the void, the vertigo of an obligation devoid of sense, a passion for necessity. - Baudrillard, Seduction

December 16, 2007

The ridiculous-sublime

My essay on Basic Instinct 2, which substantially augments the remarks I initially made about the film here, is included in the new issue of Film-Philosophy, edited by Ben Noys.

December 15, 2007

Freaks like us

My end of year round-up for Fact, written a while back, and a bit out of date since it doesn't include Bassline House, which would have fitted well into the vocal science/ electropop thread I was following and celebrating. There's a Bassline remix of 'Slave 4 U' doing the rounds as it happens. What's great about Blackout is the way that Britney seems to enjoy and acclerate her dis-integration as an organic individual - the record, like the media coverage, is a 'piece of her', a fragment of a distributed, mostly simulated, hyperbody, exhibited in a cyberspatial freakshow.

Freakery is also a fixation of Bassline. In much US R&B (most famously, Adina Howard's 'Freak Like Me') 'freak' is a euphemism for sex. In Bassline, 'freak' seems to indicate a mode of electro-libido, a cartoonish exuberance, that has little to do with genitality. In its sensibility if not its sound, Bassline has far more in common with the getting-stupid twisted clown face of Funkadelia than the moody screwface of hip hop. TS7 and TRC's 'Circus Freak' is perfectly titled: like much classic Rave, Bassline's (un)natural environment seems to be the fairground as much as the dancefloor. If you listen to the Pure TS7 mix uploaded by Smugpolice - a massive shout of appreciation for Continuum for these uploads - much of it sounds like the melted angles, pulses and bleeps of a wibbly wobbly weird amusement park. Bassline relishes the Fruity Looped Freakish absurdity of the Hardcore Continuum - the result is more often than not a sound that is more abstract and experimental than anything that can be achieved under the oppressive, self-conscious glares of studiedly morose young men. One thing I enjoy about Bassline is the almost catatonic quality of some of the vocals, a welcome alternative to the vibrato-heavy straining of X-Factor-style emoting. Like 'Heartbroken', Zoe's 'Lately' (probably my favourite Bassline track to date) is characterised by the contrast between the subdued sadness of the vocal and the barrel-organ carny momentum, the oozing exhilaration, of the backing.

At the same time, another thing that I enjoy about Bassline is the way that it has repotentiated Grime and Dubstep. It's done that by effectively re-establishing a Garage mainstream. Grime and Dubstep always felt like dead ends - but that ceases to be the case when there is a pop alternative for them to play off, when there is a Garage mainstream which they can pass in and out of - one of my favourite Bassline tracks at the moment is DJ Q's remix of Dizzee's 'Flex'. Grime has been bedeviled by comparisons with US hip hop; but if it is drawn out of its skunk-fugged cul-de-sac and back into the Garage continuum, it avoids seeming like some bargain basement version of rap.

December 10, 2007

Metadub

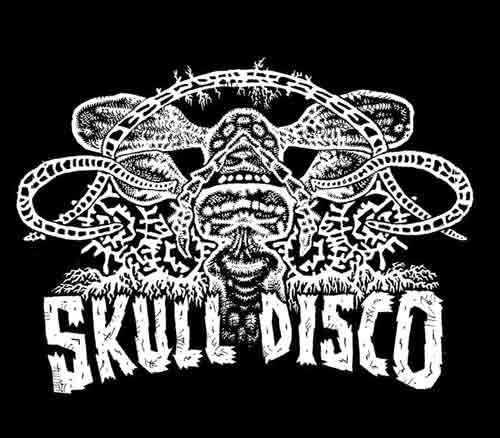

Me on Skull Disco, Kode9 and The Bug at the recent Metadub event at Plastic People, on the Frieze website.

December 08, 2007

A memory that isn't yours

- There’s a few ghost stories, the one that fucked me up when I was little. 'Oh Whistle and I'll Come To You My Lad'. Something can betray how sinister it is even at a distance. Something weird happens with M R James, because they’re short - and I don’t read much – and even though it’s in writing, there’ll be a moment, when the person meets the ghost, where you can’t quite believe what you’ve read, you go cold, just for those few lines when you glimpse the ghost for a second, or he describes the ghost face. It's like you’re not reading any more. In that moment it burns a memory into you that isn't yours. He says something like, ‘there’s nothing worse for a human being than to see a face where it doesn’t belong’. But if you’re little, and you’ve got an imagination which is always messing you up and darking you out, things like that are almost comforting to read. Also, there is nothing worse than not recognizing someone you know, someone close, family, seeing a look in them that just isn't them. I was once in a lock-in in a pub and the regulars there and some mates started telling these fucked up ghost stories from real life, maybe that had happened to them, and I swear if you heard them. One girl told me the scariest thing I ever heard. Some of these stories would stop a few words earlier than seemed right, they don't play out like a film, they're too simple, too everyday, slight, those stories ring true and I never forgot them. Sometimes maybe you see ghosts on the underground with an empty Costcutters plastic bag, nowhere to go. They are smaller, about 70% smaller than a normal person, smaller than they were in life.

From the unedited transcript of my interview with Burial, now up on The Wire site.

December 07, 2007

Hey Mark

I will be a keynote speaker at the following:

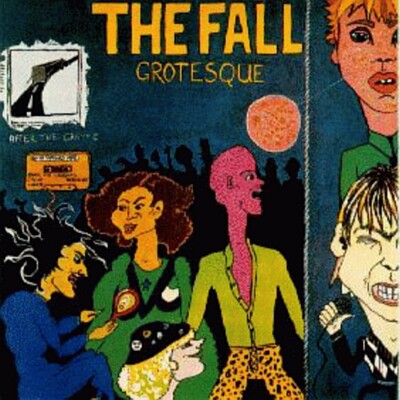

- MESSING UP THE PAINTWORK

A Conference on the Aesthetics and Politics of Mark E. Smith and The Fall

Mark E. Smith remains one of the most interesting and idiosyncratic figures in popular music after a recording career with his band The Fall that spans 30 years. While The Fall were originally associated with the contemporaneous punk explosion, from the beginning they pursued a highly original vision of what was possible in the sphere of popular music. While other punk bands died out after a few years only to reform twenty years later as their own cover bands, The Fall continued evolving, while at the same time retaining a remarkable consistency despite frequent line-up changes that soon left Mark E. Smith as the one permanent member of the group. More than this both Mark E. Smith’s lyrics and the music of the group itself seem to reincarnate many twentieth century currents from modernist aesthetics to pulp fiction, for example in Smith’s well-known fascination with “Weird Tales” and writers as diverse as M. R. James, H. P. Lovecraft and Wyndham Lewis. At the same time, Mark E. Smith never wanted to be known as even a punk poet and his lyrics have always been inseparable from working with or rather against the changing members of his group. These antagonistic relations bring us to the difficult question of the politics of Mark E. Smith that have been interpreted as everything from working class conservatism to extreme radicalism and have seemed to constantly shift and mutate over the years. Perhaps the key aspect of the group that the conference will bring out is precisely the centrality of antagonism to Mark E. Smith and The Fall as a strictly maintained critical attitude to everything from musicians within The Fall to the wider musical and cultural sphere.

Paper proposals are being solicited for this conference, which will aim to address some of the following issues in relation to Mark E. Smith and The Fall:

* The Fall in relation to the Manchester music scene from 1977 to the present

* The Fall and their punk and art-punk contemporaries (The Buzzcocks, The Mekons, Joy Division etc.)

* The Fall and antagonism both within the group and with the wider musical and cultural field

* Mark E. Smith and ‘Pulp Modernism’; The Fall in relation to 20th Century aesthetics

* The cultural politics of Mark E. Smith and The Fall

* Mark E. Smith and (Northern) working class culture

* Ghosts and hauntings in The Fall, from pulp horror to rock music to radical politics

* Extra-musical projects and collaborations (Michael Clarke, I am Curious Oranj etc.)

* The Fall and contemporary music; influences and further antagonisms

The symposium will take place at the University of Salford on the 2nd of May, 2008 and will be hosted by the Communication, Cultural & Media Studies Research Centre (www.ccm.salford.ac.uk). If you are interested in participating, please send abstracts and a short bio to Michael Goddard, m.n.goddard@salford.ac.uk, to be received no later than 16 January 2008.

Registration for the event will be £30.

December 04, 2007

Cinemascope

- ArtHertz presents Cinemascope – A solo exhibition of new print and photographic works by John Foxx

The Coningsby Gallery

30 Tottenham Street W1T 4RJ

3rd December – 8th December 2007

The Coningsby Show is a unique opportunity to view his new and recent work – Grey Suit Music and Tiny Colour Movies stills, together with images from the critically acclaimed Cathedral Oceans III.

December 03, 2007

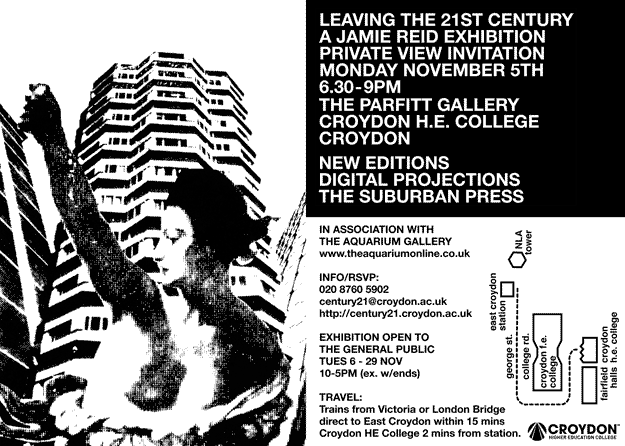

Re-entering the Twentieth Century

(Here's some text I provided for the recent Jamie Reid exhibition at Croydon H E College).

Leave the twentieth century? We have to get back there first. Stranded here, at the end of History, in the drear grip of the post-1989 Restoration (of family values, economism), the 20th century seems impossibly modern.

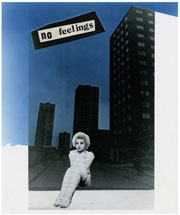

Many of Jamie Reid’s most important images are presided over by the ambivalent figure of the tower block. The official judgement promulgated at the end of History is that the tower block was an abomination, the relic of a degenerate and unworkable project to engineer a new kind of public space. Look at Reid’s work from the 1960s and 1970s now and you are taken back to the struggle over urban planning that was at the heart of the 20th century. Would the city be the execution of a Radiant masterplan or the site of a permanent dérive? In either case, the city was envisaged as a the habitat for a new kind of human. In the 21st century, such humans can no longer be imagined. Only ‘nice families’ living in ‘nice houses’ are welcome here. Centralised planning has been replaced by a control apparatus whose implacable despotism cloaks itself with the appearance of public consultation and consumer preference. But did anyone ask you whether you wanted London to be gradually, greedily consumed by the 2012 SF Capital Megatastrophe?

The tower block was a precondition for punk, and it was only in its more conservative moments that punk lapsed into a humanist protest against the alienating effects of brutalist architecture. Punk was far more interesting when it could be heard as a cry of exuberant alienation which rejected beaches in favour of pavement, which preferred concrete to a ‘Nature’ it derisively exposed as a reification.

Capitalist realism – the idea that capitalism is the inevitable terminus awaiting all societies fortunate enough to reach the End of History – relies on a naturalization of current social conditions, a naturalization that photoshops out politics and replaces it with TV parliamentarianism. The significance of Jamie Reid’s work was always to estrange the environment presented to us as natural by advertising. All culture in the 21st century tends to the condition of advertising. More than ever, we live inside adverts and adverts are inside us. The environments we move through are walk-through, interpassive simulations, and we are the carriers of a pulsing videodrome signal that has colonized our unconscious, secreting its banal aspirations into our electric dreams. Specific adverts sell products, but the form of advertising sells Capital itself. Nothing else is on offer.

Reid’s work reminds us of a time when it seemed possible to step outside the banalizing boulevards of advertising, to a time, that is to say, when the strategy of detournement had not itself been incorporated into the massive recuperation that is postmodernism, the cultural logical of late capitalism. Late capitalism’s wrap-around, seamless, CGI-enhanced semiotic terrain is so totally pervasive that it makes the idea of a Spectacle seem quaint. Where is the new Jamie Reid who can rouse us from our Restoration stupor, where is the cyberpunk that can blast a hole in the naturalised Graphic-User Interface of late capital’s mega-Matrix?