November 29, 2007

I put my finger on the weird...

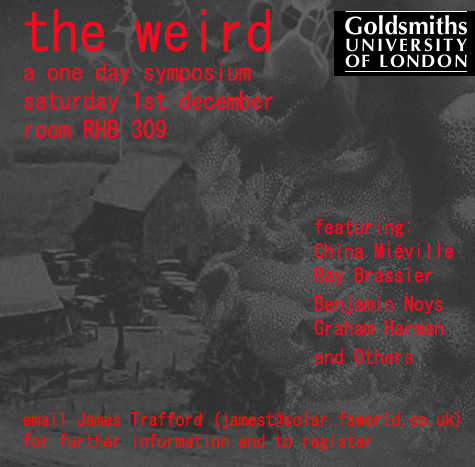

A reminder that the Weird event is taking place on Saturday at Goldsmiths. It's free of charge so if you around in London this week, please come along. The event is not intended for philosophy specialists, and will be centred on discussion rather than the delivery of papers. The speakers, all of whom have written and theorized about the Weird for a number of years, come from a variety of backgrounds and perspectives. New additions to the bill include Dean Kenning, the artist responsible for the recent 'The Dulwich Horror- H.P. Lovecraft and the Crisis in British Housing' exhibition, and Andy Sharp of English Heretic. The event is scheduled to start at noon. The text below will serve as the basis for my presentation.

The Door in the Wall: The Weird, worlds and the worldly

What follows is a reading of Wells’ extraordinary short story ‘The Door in the Wall’ (1911). It’s my conjecture that this story exemplifies a number of the defining features of the Weird, which I will seek to analyse and enumerate below.

‘The Door in the Wall’ is of particular interest because it is differs in several significant respects from Lovecraft’s tales. This is important, since any coherent and useable concept of the Weird must be applicable to more than the works of Lovecraft. Comparing Lovecraft’s stories to other examples of the Weird will allow us to begin to distinguish general properties of the Weird from particular techniques used by Lovecraft.

The most obvious point of departure from the formula of the Lovecraftian tale is the lack of any inhuman entities in ‘The Door in the Wall’. When Wallace passes through the door, he encounters strange beings, but they appear to be human. The feeling of the Weird that the story gives rise to is clearly not primarily produced by these languid, beneficent beings; and I want to argue further that the Weird does not require any of the ‘abominable monstrosities’ which are so central to Lovecraft’s tales.

The second way in which ‘The Door in the Wall’ deviates from the Lovecraftian model is the question of ontological hesitation. At the end of ‘The Door in the Wall’, Wells’ narrator, Redmond, finds his mind ‘darkened with questions and riddles’. He cannot dismiss the possibility that Wallace was suffering from an ‘unprecedented type of hallucination’. It is likely that Todorov would treat Wells’ story as a classic example of the Fantastic, since, at first glance, ‘The Door in the Wall’ seems to be poised in a state of unresolved tension between the Marvellous (the supernatural) and the Uncanny (in which the apparently supernatural is explained naturalistically). At the climax of a Lovecraft tale, by contrast, we can be sure that the Other world which the characters have encountered is real.

This leads to a third difference, which might possibly be subsumed into the second: the question of insanity. In Lovecraft’s tales, any insanity the characters experience is a consequence of the transcendental shock that the encounter produces; there is no question of the insanity causing characters to perceive the entities (whose status would then, evidently, be degraded; they would merely be products of a delirium). ‘The Door in the Wall’ leaves open the question of psychosis: it is possible – though Redmond doubts it, it is not his ‘profoundest belief’ – that Wallace is mad, or is deluded, or has confabulated the whole experience from garbled childhood memories (which, to use a distinction from Freud’s essay on ‘Screen Memory’ would then be memories of childhood, not memories from childhood). Wallace himself suspects that he may have augmented a childhood memory – re-dreamed it – to the point of completely distorting it. "I dreamt often of the garden. I may have added to it, I may have changed it; I do not know . . . . . All this you understand is an attempt to reconstruct from fragmentary memories a very early experience. Between that and the other consecutive memories of my boyhood there is a gulf. A time came when it seemed impossible I should ever speak of that wonder glimpse again."

With ‘The Door in the Wall’, the ontological question is not so much about the reality or not of the supernatural – there is nothing to suggest that the world behind the wall is ‘supernatural’, though it is certainly ‘enchanted’ - but about the opposition between the quotidian and the numinous. Wallace’s description of an ‘indescribable quality of translucent unreality, [different] from the common things of experience that hung about it all’ recalls Otto’s characterisation of the numinous in The Idea of the Holy. Yet, for both Wallace and Otto, an ‘indescribable quality of translucent unreality’ precisely accompanies encounters with that which is more real than ‘the common things of experience’. ‘To [Wallace] at least the Door in the Wall was a real door leading through a real wall to immortal realities.’

I wrote above that ‘The Door in the Wall’ turns on an ontological hesitation. This is misleading. In fact, ‘The Door in the Wall’ hesitates between an ontological resolution, in which Wallace really has made contact with an Other world, and an epistemological resolution, in which Wallace is suffering from some kind of delusion. Wallace is either a madman or a ‘dreamer, a man of vision and the imagination’. ‘We see our world fair and common,’ Redmond concludes, inconclusively, ‘the hoarding and the pit. By our daylight standard he walked out of security into darkness, danger and death. But did he see like that?’

Thresholds

It is this question of Worlds – and of contact between worlds – that I want to argue is central to the Weird. Weird fiction presents us with a threshold between worlds. ‘The Door in the Wall’ is, evidently, about just such a threshold. Much of its power derives from the opposition between the mundanity of the London setting, with its minutely delineated quotidiana - ‘he recalls a number of mean, dirty shops, and particularly that of a plumber and decorator, with a dusty disorder of earthenware pipes, sheet lead ball taps, pattern books of wall paper, and tins of enamel’ – and the ‘secret and peculiar passage of escape into another and altogether more beautiful world’.

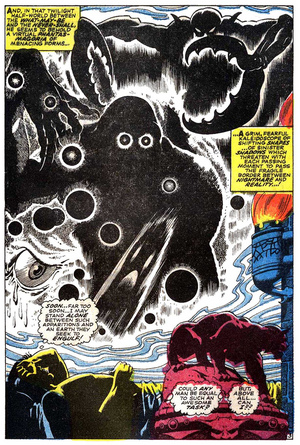

Lovecraft’s stories are full of thresholds between worlds: often the egress will be a book (the dread Necromonicon), sometimes, as in the case of the Randolph Carter ‘Silver Key’ stories, it is literally a portal. Gateways and portals routinely feature in the deeply Lovecraftian stories of the Marvel comics character Doctor Strange. David Lynch’s film and television work is similarly fixated on doorways, curtains and gateways: Inland Empire appears to be a ‘holey space’ constructed out of thresholds between worlds, an ontological rabbit warren. Sometimes the threshold may only be a matter of re-scaling: Matheson’s The Incredible Shrinking Man demonstrates that your own living room can be a space of Weird wonder and dread if you become sufficiently small.

Between worlds

The notion of the between is crucial to the Weird. It is clear that if Wells’ story had taken place only in the Garden behind the wall, then no Weird charge would have been produced. In that situation, we would be in the realm of Fantasy (by which I obviously do not mean Todorov’s ‘Fantastic’, but ‘Fantasy’ in the sense that is used in contemporary fiction publishing). This mode of Fantasy naturalises OtherWorlds. But the Weird de-naturalises all worlds, in part by always prompting the question: what is a world? (this ontological estrangement-effect may be its most important political effect).

The Weird tale presents an Ontological montage in which a world – usually ‘our’ world, the world captured by naturalistic description and governed by commonsense – is ruptured or interrupted by what does not belong to it: that which is ‘out of space’, and/ or ‘out of time’. Lovecraft’s major breakthrough was perhaps his setting of his stories in a familiar New England setting (his earliest stories had taken place in a heightened Dunsanian OtherWorld). Similarly, Ramsey Campbell began by imitating Lovecraft, but his fiction only achieved a Weird effect when he started to set it in a naturalistic Liverpool. Ligotti’s most successful fiction, Crampton, is so powerful because its Weird involutions of time and space, its ontological haemorrhages, take place in a well-drawn naturalistic setting.

Graham Harman parallels the effect of ‘unvisualisability’ in Lovecraft’s text with the techniques of cubism; but the Weird also has a strong affinity with the textural discrepancies of collage. The Weird does not airbrush or photoshop incommensurable elements into a seamless CGI simulation; rather it insists upon, and consists in, the very incommensurability. That is why Julian House’s Lovecraft-inspired collages (see immediately below) are such apposite illustrations for the Weird.

Beyond the worldly

The Weird always expresses a dis-satisfaction with the worldly, the mundane. That is one way in which the Weird can be said to differ from Horror. There is certainly a crossover of the Weird and Horror – in many ways, Lovecraft is that crossover – but the Things of the Weird are never merely horrible or terrifying. If they elicit a shudder, it is not merely a shudder of fear, but a shudder of ontological unease that typically contains a thrill of wonder, a vertiginous delight that there is something beyond the mean confines of the mundane. It is clear, for example, that no matter how many negative adjectives Lovecraft piles onto his abominable entities, they are objects of wonder as much as dread.

The attack on the deficiencies of the worldly is of course explicit in ‘The Door in the Wall’. "Oh! the wretchedness of that return!" Redmond complains, when he finds himself back in ‘this grey world again’. Redmond attributes his ‘quite ungovernable grief’ to a failure of fidelity to the Weird.

- "Well", he said and sighed, "I have served that career. I have done--much work, much hard work. But I have dreamt of the enchanted garden a thousand dreams, and seen its door, or at least glimpsed its door, four times since then. Yes--four times. For a while this world was so bright and interesting, seemed so full of meaning and opportunity that the half-effaced charm of the garden was by comparison gentle and remote. Who wants to pat panthers on the way to dinner with pretty women and distinguished men?”

Wallace feels that he is depressed – ‘the keen brightness that makes effort easy has gone out of things recently’ - because he has yielded to the temptations of the worldly, failed to keep faith with ‘the haunting memory of a beauty and a happiness that filled his heart with insatiable longings that made all the interests and spectacle of worldly life seem dull and tedious and vain to him’.

- "Here I am!" he repeated, "and my chance has gone from me. Three times in one year the door has been offered me--the door that goes into peace, into delight, into a beauty beyond dreaming, a kindness no man on earth can know.”

Thus Wallace finds himself – adopting for a moment the perspective of a worldliness he has now almost entirely rejected - “grieving--sometimes near audibly lamenting--for a door, for a garden!"

The Weird and Psychoanalysis

When Wallace describes his grief, he seems to be a plaything of our old friend, the death drive. "The fact is--it isn't a case of ghosts or apparitions--but--it's an odd thing to tell of, --I am haunted. I am haunted by something--that rather takes the light out of things, that fills me with longings . . . . ." The pull exerted by the door and the garden deprives all of his worldly satisfactions and achievements of their flavour.

- Now that I have the clue to it, the thing seems written visibly in his face. I have a photograph in which that look of detachment has been caught and intensified. It reminds me of what a woman once said of him--a woman who had loved him greatly. "Suddenly," she said, "the interest goes out of him. He forgets you. He doesn't care a rap for you--under his very nose . . . . ."

The door was far from the start an ambivalent object, a threshold leading beyond the pleasure principle: ‘he did at the very first sight of that door experience a peculiar emotion, an attraction, a desire to get to the door and open it and walk in’. Redmond then imagines ‘the figure of that little boy, drawn and repelled’ (emphasis added).

Is there something inherently Weird about the death drive? There are grounds for saying that the greatest of all fictions about the death drive – Melville’s Moby Dick – is a vastly distended Weird Tale. ‘“What is it,” asks Ahab,

- what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozzening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is Ahab, Ahab?”

Psychoanalysis, whose object of study and treatment is those ‘nameless, inscrutable, unearthly things’ that go ‘against all natural lovings and longings’, can be – and usually is - placed under the sign of the Uncanny. Freud’s great essay on ‘The Uncanny’ – with all its ambivalences, its repetitions, its over-hasty closures – remains the most potent theorization of the uncanny. The domain of psychoanalysis can be seen as the place of the unheimlich or the unhomely, the estranged familiar/ familial. But can’t the unconscious also be considered Weird, with psychoanalysis the threshold into its alien world? Is Lacanianism – which drew upon the same Surrealist and Modernist collage-art which fascinated and repelled Lovecraft – the revenge of the Weird upon Freud’s tendency towards homeliness? Certainly, ‘The Door in the Wall’ seems to belong to a ‘Lacanian Weird’ but is the Weird inherently Lacanian, or is Lacanianism just one mode of the Weird?