November 29, 2006

'What is best left alone, that accursed thing is not always what least allures.'

- What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozzening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm? But if the great sun move not of himself; but is as an errand-boy in heaven; nor one single star can revolve, but by some invisible power; how then can this one small heart beat; this one small brain think thoughts; unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I. By heaven, man, we are turned round and round in this world, like yonder windlass, and Fate is the handspike.

Moby Dick, Chapter 131, 'The Symphony'

I finally finished Moby Dick, after making at least two previous abortive attempts over the last twenty years. The novel contains multitudes, of course, but it impressed me this time as a study of death drive, whose characteristics are nowhere better anatomised than in Ahab's speech above, perhaps the most powerful in the novel. Here, at the white-water heart of Melville's maelstrom, indifferent Fate and a blind, deranged Deity, doubling each other, emerge as avatars of death drive: the 'nameless, inscrutable, unearthly' 'hidden lord and master that against all natural lovings and longings' recklessly makes Ahab 'ready to do what in [his] own proper, natural heart, [he] durst not so much as dare'.

'Nameless, inscrutable, unearthly...' Melville's characterization of demiurgic Fate sounds like an anticipation of Lovecraft, and Melville's prodigy - a spawn of Poe, as well as an antecedent of Cthulhu - could be described as a monstrously distended Weird Tale. It is certainly a Queer tale, with Ahab - who has abandoned his young wife and child - leading his male crew (among them the 'ambiguously intertwined' Ishmael and Queequeg) away from domesticity and reproductive futurism into the ruinous embrace of Thanatos.

Is Ahab, Ahab indeed? A question whose surface simplicity incubates countless metaphysical provocations. Ahab is Ahab only insofar as he is more than Ahab, only insofar as he is the host and vessel for a crazed, senseless trieb that exceeds any 'natural longings'. '[I]n Ahab's case, yielding up all his thoughts and fancies to his one supreme purpose; that purpose, by its own sheer inveteracy of will, forced itself against gods and devils into a kind of self-assumed, independent being of its own.'

At the same time, Ahab is Ahab only insofar as he is less than Ahab, only insofar as he will never achieve the self-possession of identity, that he will be forever riven, split - as Ahab is, literally, scarred by a lightning strike. ('Threading its way out from among his grey hairs, and continuing right down one side of his tawny scorched face and neck, till it disappeared in his clothing, you saw a slender rod-like mark, lividly whitish. It resembled that perpendicular seam sometimes made in the straight, lofty trunk of a great tree, when the upper lightning tearingly darts down it, and without wrenching a single twig, peels and grooves out the bark from top to bottom, ere running off into the soil, leaving the tree still greenly alive, but branded.')

The white whale, needless to say, is the object-cause of mutilated Ahab's mad desire; the whale's snatching of a piece of him (his leg) prompting his seemingly senseless quest for revenge. Ahab's monomania is matched only by the coolness of his (self-)diagnosis; he embraces his pyschopathology, he does not shy away from it. Witness, for instance, his confession, in i'The Cabin', that 'my malady becomes my most desired health'. Later, Ahab concedes that the white whale is best left alone, only to deadpan that 'what is best left alone, that accursed thing is not always what least allures.'

Is not Ahab the archetypal obsessive? According to Lacan, the question that the obsessive is posing is: 'Am I alive or am I dead?' As Sinthome explained in a typically fabulous recent post: 'The question of whether I am alive or dead is ... a question about whether or not I must sacrifice all my jouissance, and is premised on the fantasy that I might eventually obtain total or complete jouissance by besting the master.'

Ahab is well aware that the white whale, aka Moby Dick, aka the phallus, only stands in for the Master. In a famous early exchange, Ahab is upbraided by his pragmatic first Mate, Starbuck, for attempting 'vengeance on a dumb brute ... that simply smote thee from blindest instinct!' When Starbuck protests that 'to be enraged with a dumb thing, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous', Ahab responds by proclaiming what is in effect a Gnostic vision: 'all visible objects, man,' he preaches, 'are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event--in the living act, the undoubted deed--there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask.'

In the whiteness of the whale - its void blankness - the true structure of the cosmos, its secret malignancy, is made suddenly and horribly visible. For Ahab, accident is the disguise in which an occulted Necessity, a reasoning power lurking behind (and within) the appearance of happenstance, masks itself.

Yet doesn't this vision of a malevolent order, a demiurgic pattern beneath the appearance of randomness, ward off another horror? Ahab's inhuman desire may be a sickness, but it is not melancholia. The melancholic possesses the object of desire, but deprived of its cause, so that the seemingly captured desired Thing recedes, relapses into brute, meaningless materiality, like a rubber mask removed from a face.

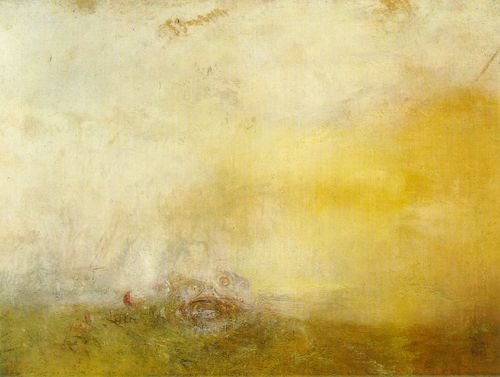

The sheer futility of Ahab's quest means that he has the cause but never the object of desire. He will thus never fall prey to melancholia, that condition in which the world appears white, colourless, because the 'madness' of human desire has been subtracted from it. Without fantasy, the world is void, deprived of all consistency. The whiteness of the whale is the blank screen on which Ahab imposes his fantasies, the fantasies that make the world make sense (a diseased kind of sense, naturally, but a sense nonetheless).

- Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way? Or is it, that as in essence whiteness is not so much a color as the visible absence of color, and at the same time the concrete of all colors; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows --a colorless, all-color of atheism from which we shrink? And when we consider that other theory of the natural philosophers, that all other earthly hues --every stately or lovely emblazoning --the sweet tinges of sunset skies and woods; yea, and the gilded velvets of butterflies, and the butterfly cheeks of young girls; all these are but subtile deceits, not actually inherent in substances, but only laid on from without; so that all deified Nature absolutely paints like the harlot, whose allurements cover nothing but the charnel-house within; and when we proceed further, and consider that the mystical cosmetic which produces every one of her hues, the great principle of light, for ever remains white or colorless in itself, and if operating without medium upon matter, would touch all objects, even tulips and roses, with its own blank tinge --pondering all this, the palsied universe lies before us a leper.... - Moby Dick, Chapter 42, 'The Whiteness of the Whale'

November 28, 2006

Apologies for lack of activity recently hereabouts... I've barely been home in the last couple of weeks; last week I was preparing for Saturday's event at Newcastle University with Jodi Dean and Mladen Dolar, organised by the excellent Blah-feme and Spurious (See Jodi's report.) In any case, there should be a proper post up tomorrow...

November 15, 2006

Ontological rot

I present below a piece on Nigel Cooke which was originally intended to be published in the Portuguese magazine, Slang; sadly the magazine has folded, so waste not, want not... I think I compared Cooke to Burial in the first post I wrote on the album...

.jpg) | .jpg) |

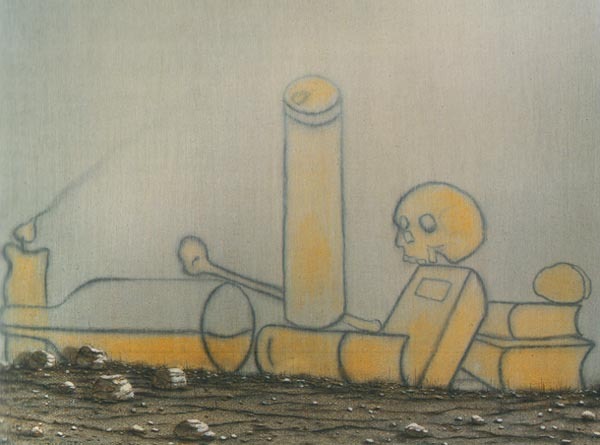

The theme of Nigel Cooke's paintings, a small number of which were exhibited in his show 'A Portrait of Everything' at the South London Gallery earlier this year, might best be described as ontological rot.

Cooke's work explicitly presents us with what seem to be (at least) two different realities, both decaying. His foregrounds, typically, are ultra-naturalistic (christmas card snow scenes are a particular favourite). The backgrounds, meanwhile, are desolated, empty to the point of being Tanguy-abstract. Typically, they are also defaced by graffiti.

Why is Cooke so fascinated with graffiti? He has described the rendering of graffiti in his painting – he uses oil paints to create the effect – as 'slowed down street language', and there is a way in which his paintings function like a motion capturing device, transliterating the energies of urban culture into paint. This is painting after hip hop and jungle, with the paintings' 'impossible architectures' paralleling the bizarre topologies invented by sampler-based sonic productions.

.jpg)

Richard Dadd, The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke (1855-1864)

The graffiti in Cooke's paintings seems to do two things at once: it does ontological violence to the represented reality of the paintings by drawing our attention to the fact that, after all, the painting is nothing more than a flat surface - it tells us what we already know: this is not a world. At the same time, the graffiti constitutes itself as a reality, a painting within a painting (or perhaps a painting over a painting): this is a world, it insists. And, immediately, we have to infer the existence of yet another reality, this time unseen - the reality of the graffiti-painter, the 'idiot' author who has defaced the represented world of the painting. Here we are in the painting equivalent of the textual labyrinths designed by Beckett, Borges or Robbe-Grillet, but instead of embedded authors, we have an embedded painter, a creature-turned-creator, a golem-become-god, a drunken demiurge who must conjure a world with only a spraycan to hand.

Nigel Cooke, The Philosopher (2005)

What kind of world does Cooke's wounded god dream up? It is a world – let us call it late capitalism – of the rejected, the dejected and the addicted. When he spoke at the Tate a few months ago about the relationship between his work and the Gothic, Cooke described his anthropomorphic flowers and vegetables as figures from advertising or children's stories who have grown up and found themselves in dead-end jobs.

.jpg)

Nigel Cooke, Thinking (2005)

The graffitied figures on/in the paintings - the junkie vegetables, the smoking flowers, the morose, hungry bones - can be related, not only to their sprightlier cousins in advertising, but to their ancestors in fairy paintings. What have fairy myths been about, after all, if not a world hidden within our world? The fairy world – vivid, hyperdetailed - was a delirial aristocracy, often cruel and exploitative, dreamt up by minds intoxicated with psilocybin. The drug analogue for Cooke's fairy gardens gone to seed would not be a fungus consumed on some greed glade but housing estate heroin. The flowerbeds have become a junkyard. They are not teeming with a fecund, indominitable Life, but populated by creatures who have taken one step towards animation, then fallen back into the mineral condition of addiction. The paintings are illustrations for fairy tales re-written by the Freud of Beyond the Pleasure Principle.

Nigel Cooke, Beer and Wine (2005)

A timeless image of Death lies miserable in front of us. A pathetic cowled bone. It could be a medieval plague victim or a kid in a hooded top stalking a shopping mall.

Graffiti painters, Baudrillard enthused in 1977, free walls 'from architecture and turn them again into living, social matter.' In Cooke's paintings, by contrast, graffiti turns living, organic landscapes into walls. The rural-vital becomes the urban-undead. Cooke described his paintings as a 'flawed idea of representing the after-life', saying that they were 'a frontier site where paintings go to die, an elephant's graveyard of images.'

Nigel Cooke, The Dead (2005)

It seems that all the worlds are rotting at once. The colours are fading. Everything looks washed out. Morning has broken, and there is no-one to fix it.

Thanks to Karl Kraft for the scans, and for introducing me to Cooke

November 04, 2006

Can it be that it was all so simple then?

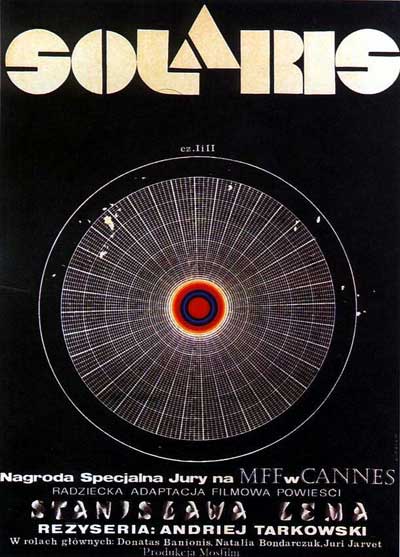

The reality of nostalgia is nowhere better invoked than at the end of Tarkovsky's Solaris. When the camera pans away from Kelvin embracing his father on the rain-soaked steps of his dacha, we realise that the scene is yet another of the simulations produced by the inscrutable planet. The whole film can be read as a treatise on the dangers and seductions of nostalgic desire. With the perversity of literalism, the revenants that the planet throws up consist of nothing but memory, and in the grotesque absurdities of Kelvin's relationship with his wife's double, Solaris demonstrates that desire may well depend upon the inhuman partner, but the inhuman partner alone can only be an object of horror. (And what is this dreaming ocean - absolutely alien to us, yet horribly aware of our every desire and memory - if not the unconscious itself?)

Tarkovsky's film ends with a simulation of a place - the Russia that Tarkovsky would soon lose, and which he would pine for in his own Nostalgia. The elision between time and space in nostalgia - as Simon tells us, nostalgia was originally defined as an intense longing for a place, before it was thought of as a craving for the past - is easy to credit. (Simon is right that the precedence of the spatial over the temporal holds even if 'nostos' originally meant 'return' rather than 'homeland'. Interestingly, of course, 'return' carries both spatial and temporal connotations.)

No doubt the fantasy of time travel is so powerful because the idea that the past is waiting somewhere, pristine, intact, awaiting our return, is so hard to eradicate from the unconscious. Nostalgia reverses the sense of Hartley's epigram whilst retaining its equation of lost time with a faraway place: the past is not a foreign country but a homeland. Here we must recall one of the most famous passages in Freud's essay on 'The Uncanny':

- It often happens that neurotic men declare that they feel there is something uncanny about the female genital organs. This unheimlich place, however, is the entrance to the former Heim [home] of all human beings, to the place where each one of us lived once upon a time and in the beginning. There is a joking saying that ‘Love is home-sickness’; and whenever a man dreams of a place or a country and says to himself, while he is still dreaming: ‘this place is familiar to me, I’ve been here before’, we may interpret the place as being his mother’s genitals or her body. In this case too, then, the unheimlich is what was once heimisch, familiar; the prefix ‘un’ [‘un-’] is the token of repression.

What Freud calls the 'lascivious' fantasy of 'intra-uterine existence' seeks something impossible, and not only physically. The logic of desire is itself contradictory: what is sought is a conscious experience of a dissolution of the ego, the very seat of consciousness. If this is the model for all nostalgia, then it is clear that the nostalgic desire seeks something more unattainable even than the recovery of the past; it wants the past as seen from now. The past which we had to live through headlong can be savoured only now that it has been subtracted from the flow of becoming.

Thomas Hardy's poems, topical at the moment because of Claire Tomalin's Time-Torn Man, (a 'haunted and haunting biography' according to Hilary Spurling in The Observer) bring out this dimension of nostalgia with a peculiar power. 'The Self-Unseeing' pictures Hardy - doubled like Spider in Cronenberg's film, an observer of the past and an actor in it - watching a bucolically re-staged scene from long ago: 'Childlike, I danced in a dream;/ Blessings emblazoned that day/ Everything glowed with a gleam; Yet we were looking away!' And yet it is clear that the 'gleam' depends upon the 'looking away'; it is something that the scene has acquired by virtue of a long period of time having elapsed. What is mourned for is an unselfconscious casualness; what is wanted is the possibility of experiencing those moments again, but with the added piquancy brought by age and loss. Again, this is not only empirically impossible; to re-experience the past like this would be to lose the very lightness that is yearned for in it.

In his later years, Hardy retreated from the modern world his novels had confronted (a world that, in many ways, he saw as not modern enough; Jude, for instance, was destroyed by the dead man's grip of a past) and gave himself over to composing a lyric poetry decorated with archaic diction. All of Hardy's love poems - written by an old man, recalling feelings he had experienced half a century before - combine nostalgia with necromancy. But the figure they are devoted to was in large part his own invention. The poems are seances that summon an inhuman partner, a fantasmatic double of his dead wife. When she was alive, Hardy's wife Emma suspected that he could only love imaginary women (she believed that he was in love with his own creation, Tess). It is ironic then that the love poetry Hardy addressed to her confirms that he could only love his own creations, since it was only when Emma herself had died and could become an imaginary woman, a 'voiceless ghost' as he put it in 'After a Journey', that Hardy could love her again. (Emma and Hardy had been effectively estranged for many ears.) 'After a Journey' makes repeated play of the doubleness of the word 'haunt', entangling a sense of the place with the call of the past in a way that is typical of all Hardy's love lyrics, which are such vivid illustrations of the nostalgic impulse in general.

What Hardy's poems shy away from is the possibility that the much longed-for past is a retrospective confabulation; that his love for Emma thrived on obstacles, and gained its impetus at the end from the most serious obstacle of all, death.

Can it be that it was all so simple then?

By contrast, the reason that 'The Way We Were' is one of the best nostalgia songs is that it is precisely about the ways in which nostalgia depends upon a falsification - a 'misty watercolouring' - of the past. When the Wu Tang Clan sampled 'The Way We Were', the line they hijacked and looped - from the Gladys Knight version, not the Streisand original - was 'can it be that it was all so simple then?', the plaintive tremor of the original now become a repeated reproach, its wraith-like insubstantiality made all the more affecting by being placed in RZA's siren-scarred brutalist NYC.

In the original, of course, this line is followed by, 'or has time rewritten every line'? The impossible existential dilemma - 'and if we had the chance to do it again/ would we?' - poses a Nietzschean challenge (one reminscent of the plight of the lovers in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind), which Hamlisch's lyrics resolve in an appropriately Nietzschean way, with an celebration of the power of forgetting (falsification as the necessary precondition for all affirmation): 'what's too painful to remember, we simply choose to forget'. We choose to forget... rather than we are unable to remember, as in trauma. We return to a past, the past does not return to (or through) us; the repetition is not a compulsion.

It strikes me, however, that the nostalgia mode is another kind of pathology altogether. The Way we Were was part of the 1970s' thematization of nostalgia, as were Roxy, whose dyschronic collages might have seemed quintessentially postmodern twenty years ago, but which now look like exercises in modernist nostalgia (with Bowlly, rock and roll and a - then still imaginable - synthetic future converging in an impossible Overlook Hotel simultaneity).

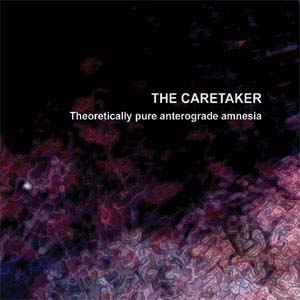

Mention of the Overlook inevitably brings to mind is the Caretaker who, with Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia has provided one of the most acute - and also, not coincidentally, one of the bleakest - diagnoses of our condition. As I put it in my sleevenotes, Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia is not about a craving for the past but inability to get out of the past. It might seem strange to suggest that our condition is amnesiac, but anterograde amnesia is the incapacity to produce new memories. Beneath the superficial bonomie of the endless television rundowns (100 bests, I Love 1971-2-3-4......), Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia finds a dementia. The young have become like the very old, living in a past that they confuse with the present. More horrible than being trapped in one's own reminiscences, this is about being condemned to forever wander someone else's memory lanes (a fate which cannot but remind us of Rachel's situation in Blade Runner). The present looms emptily, an unsymbolizable abstraction, an abandoned echo chamber, forbidding in its abstraction; the only landmarks are the fragments of the past which flare intermittently in the murk. The genius of Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia is that it reinforces the very condition it describes; the seventy odd tracks, each one Beckett-sparse, are impossible to remember - each time you hear them, it is as if for the first time (even though the first time was already an instance of deja entendu).

November 01, 2006

The third place, again

- Indeed, it may be the iPod's role in constructing the illusion of a home away from home that is the most monstrous thing of all. As cultural critics are fond of pointing out, the German title of Sigmund Freud's famous essay on the uncanny, Das Unheimliche, translates literally as "the un-home-like." That's an apt description of the eerie feeling we get watching people who sit for hours staring blankly into space, ears plugged with music of their choosing, looking like they've lost the passage back to the place they were before. They are out in public, to be sure, but primarily to act out their desire for privacy. Maybe what these listeners want is to be seen wanting both company and solitude.

It's a paradoxical wish, but one that captures the peculiar anxieties of the postmodern era in their most acute post-9/11 form. In the end, the iPod is the ideal product for the era of homeland insecurity.

Really excellent piece on iPods from Alternet (via Sonic Truth, which, incidentally, is also very good on Kode9 and Spaceape). The piece articulates very clearly what I was groping towards when I posited MySpace versus public space; I hadn't previously been aware that the iPod was launched in the immediate wake of 9/11. That correlation now seems incredibly suggestive ...