November 29, 2006

'What is best left alone, that accursed thing is not always what least allures.'

- What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozzening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm? But if the great sun move not of himself; but is as an errand-boy in heaven; nor one single star can revolve, but by some invisible power; how then can this one small heart beat; this one small brain think thoughts; unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I. By heaven, man, we are turned round and round in this world, like yonder windlass, and Fate is the handspike.

Moby Dick, Chapter 131, 'The Symphony'

I finally finished Moby Dick, after making at least two previous abortive attempts over the last twenty years. The novel contains multitudes, of course, but it impressed me this time as a study of death drive, whose characteristics are nowhere better anatomised than in Ahab's speech above, perhaps the most powerful in the novel. Here, at the white-water heart of Melville's maelstrom, indifferent Fate and a blind, deranged Deity, doubling each other, emerge as avatars of death drive: the 'nameless, inscrutable, unearthly' 'hidden lord and master that against all natural lovings and longings' recklessly makes Ahab 'ready to do what in [his] own proper, natural heart, [he] durst not so much as dare'.

'Nameless, inscrutable, unearthly...' Melville's characterization of demiurgic Fate sounds like an anticipation of Lovecraft, and Melville's prodigy - a spawn of Poe, as well as an antecedent of Cthulhu - could be described as a monstrously distended Weird Tale. It is certainly a Queer tale, with Ahab - who has abandoned his young wife and child - leading his male crew (among them the 'ambiguously intertwined' Ishmael and Queequeg) away from domesticity and reproductive futurism into the ruinous embrace of Thanatos.

Is Ahab, Ahab indeed? A question whose surface simplicity incubates countless metaphysical provocations. Ahab is Ahab only insofar as he is more than Ahab, only insofar as he is the host and vessel for a crazed, senseless trieb that exceeds any 'natural longings'. '[I]n Ahab's case, yielding up all his thoughts and fancies to his one supreme purpose; that purpose, by its own sheer inveteracy of will, forced itself against gods and devils into a kind of self-assumed, independent being of its own.'

At the same time, Ahab is Ahab only insofar as he is less than Ahab, only insofar as he will never achieve the self-possession of identity, that he will be forever riven, split - as Ahab is, literally, scarred by a lightning strike. ('Threading its way out from among his grey hairs, and continuing right down one side of his tawny scorched face and neck, till it disappeared in his clothing, you saw a slender rod-like mark, lividly whitish. It resembled that perpendicular seam sometimes made in the straight, lofty trunk of a great tree, when the upper lightning tearingly darts down it, and without wrenching a single twig, peels and grooves out the bark from top to bottom, ere running off into the soil, leaving the tree still greenly alive, but branded.')

The white whale, needless to say, is the object-cause of mutilated Ahab's mad desire; the whale's snatching of a piece of him (his leg) prompting his seemingly senseless quest for revenge. Ahab's monomania is matched only by the coolness of his (self-)diagnosis; he embraces his pyschopathology, he does not shy away from it. Witness, for instance, his confession, in i'The Cabin', that 'my malady becomes my most desired health'. Later, Ahab concedes that the white whale is best left alone, only to deadpan that 'what is best left alone, that accursed thing is not always what least allures.'

Is not Ahab the archetypal obsessive? According to Lacan, the question that the obsessive is posing is: 'Am I alive or am I dead?' As Sinthome explained in a typically fabulous recent post: 'The question of whether I am alive or dead is ... a question about whether or not I must sacrifice all my jouissance, and is premised on the fantasy that I might eventually obtain total or complete jouissance by besting the master.'

Ahab is well aware that the white whale, aka Moby Dick, aka the phallus, only stands in for the Master. In a famous early exchange, Ahab is upbraided by his pragmatic first Mate, Starbuck, for attempting 'vengeance on a dumb brute ... that simply smote thee from blindest instinct!' When Starbuck protests that 'to be enraged with a dumb thing, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous', Ahab responds by proclaiming what is in effect a Gnostic vision: 'all visible objects, man,' he preaches, 'are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event--in the living act, the undoubted deed--there, some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask.'

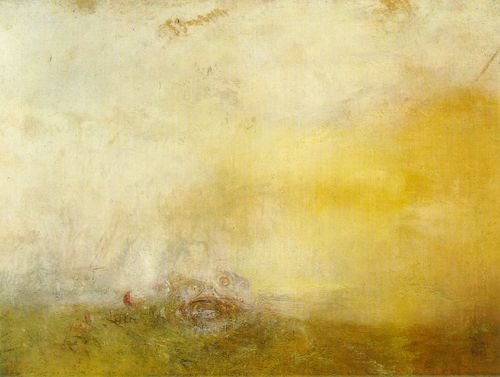

In the whiteness of the whale - its void blankness - the true structure of the cosmos, its secret malignancy, is made suddenly and horribly visible. For Ahab, accident is the disguise in which an occulted Necessity, a reasoning power lurking behind (and within) the appearance of happenstance, masks itself.

Yet doesn't this vision of a malevolent order, a demiurgic pattern beneath the appearance of randomness, ward off another horror? Ahab's inhuman desire may be a sickness, but it is not melancholia. The melancholic possesses the object of desire, but deprived of its cause, so that the seemingly captured desired Thing recedes, relapses into brute, meaningless materiality, like a rubber mask removed from a face.

The sheer futility of Ahab's quest means that he has the cause but never the object of desire. He will thus never fall prey to melancholia, that condition in which the world appears white, colourless, because the 'madness' of human desire has been subtracted from it. Without fantasy, the world is void, deprived of all consistency. The whiteness of the whale is the blank screen on which Ahab imposes his fantasies, the fantasies that make the world make sense (a diseased kind of sense, naturally, but a sense nonetheless).

- Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation, when beholding the white depths of the milky way? Or is it, that as in essence whiteness is not so much a color as the visible absence of color, and at the same time the concrete of all colors; is it for these reasons that there is such a dumb blankness, full of meaning, in a wide landscape of snows --a colorless, all-color of atheism from which we shrink? And when we consider that other theory of the natural philosophers, that all other earthly hues --every stately or lovely emblazoning --the sweet tinges of sunset skies and woods; yea, and the gilded velvets of butterflies, and the butterfly cheeks of young girls; all these are but subtile deceits, not actually inherent in substances, but only laid on from without; so that all deified Nature absolutely paints like the harlot, whose allurements cover nothing but the charnel-house within; and when we proceed further, and consider that the mystical cosmetic which produces every one of her hues, the great principle of light, for ever remains white or colorless in itself, and if operating without medium upon matter, would touch all objects, even tulips and roses, with its own blank tinge --pondering all this, the palsied universe lies before us a leper.... - Moby Dick, Chapter 42, 'The Whiteness of the Whale'