October 27, 2006

Spot the difference

|  |

OK, so we all know that Borat is humiliatingly, career-endingly unfunny (one trick too many for one-trick pony Sacha Double-Barelled) - but can anyone explain why the 'character' isn't roundly condemned for being as unacceptably racist as the one-dimensional stereotypes from 70s sitcoms such as Mind Your Language? (Could it be because Baron Cohen is middle class, I wonder?)

October 25, 2006

Nostalgic modernism

Simon is right to observe that nostalgia was a preoccupation of literary modernism: to his examples of Proust and Nabokov we can add Joyce (Ulysses as an exercise in re-creating Dublin as it was twenty years before). The difference between literary modernism and current pop, however, is that, in the case of the former, the 'search for lost time' involved the invention of new formal techniques.

I'm not sure that Gek-Opel's misgivings can be waved away by the claim that there is no pop futurism around at the moment (as I recall, Simon used the same argument to defend the Arctic Monkeys). Even if pop futurism is thin on the ground at the moment, there is still the whole history of innovation and novelty in pop; if contemporary pop fails by those standards, it should be judged accordingly, and hauntology is important precisely because it forces the comparison between present pop and its antecedents.

Gek is concerned about their being not 'enough absence, or memories of things which never existed' in Ghost Box in particular. I think that Owen's response to this anxiety identifies that there all kinds of 'what ifs' at play in Ghost Box:

- What if Thamesmead or Cumbernauld had been welcomed as modernist communities by their inhabitants, and had provided models for the rest of the country? What if the BBC Radiophonic Workshop were more important than the Beatles?

My claim would be that the Radiophonic Workshop were more important than the Beatles; that the Workshop rendered even the most experimental rock obsolete even before it had happened. But of course you are not comparing like with like here; the Beatles occupied front stage in the Pop Spectacle, whereas the Radiophonic Workshop insinuated their jingles, idents, themes and special FX into the weft of everyday life. The Workshop were properly unheimlich, unhomely, fundamentally tied up with a domestic environment that had been invaded by media. Thus, nostalgia - literally, 'homesickness', remember - for the Radiophonic Workshop involves a craving for houses haunted by weird media.

I am about the same age as Julian and Jim from Ghost Box, so my nostalgia for the 70s is evidently determined in part by the fact that I was a child in that decade. Nevertheless, I think that Owen goes some way to establishing that there was something worth remembering about the end of what was misleadingly termed the 'postwar consensus'. Looking back at the industrial unrest of the early 70s, it is hard to credit to the amount of conflict that was accepted as normal. It has been the decade and a half that has been the period of 'consensus' (= tyranny of capitalist-parliamentarian administration).

This is no licence for re-peddling the 45-79 period in pastiche packaging. But I don't believe that Ghost Box do that. They are at their most beguiling when they foreground dyschronia - as on Belbury Poly's 'Caermaen' (from The Willows) and 'Wetland' (from The Owl's Map') where folk voices summoned from beyond the grave are made to sing new songs. Dyschronia is integral to the Focus Group's whole methodology; the joins are too audible, the samples too jagged, for their tracks to sound like simulations or refurbished artifacts.

In any case, Ghost Box conjure a past that never was. Their artwork fuses the look of comprehensive school text books and public service manuals with allusions to weird fiction, a fusion that has more to do with the compressions and conflations of dreamwork than with memory. At the same time, it is worth recalling that the Radiophonic Workshop were effectively public servants, that they were employed to produce a weird public space.

The implicit demand for such a space in Ghost Box inevitably reminds us that the period since 1979 in Britain has seen the gradual but remorseless destruction of the very concept of the public. Public space has been consumed and replaced be something like the 'third place' exemplified by franchise coffee bars. Here, you are transported into the queasily inviting quasi-domesticated interior of one of SF Capital's space-ships: deterritorialization (you could be anywhere) and reterritorialization (you are in surroundings whose every nuance is shinily familar). These spaces are uncanny only in their power to replicate sameness (their voracious dominance of the high street is as visually striking a sign as you could wish for of the lie that capitalism engenders competition and diversity), and the monotony of the Starbucks environment is both reassuring and oddly disorientating; inside the pod, it's possible to literally forget what city you are in. What I have called nomadalgia is the sense of unease that these anonymous environments, more or less the same the world over, provoke; the travel sickness produced by moving through spaces that could be anywhere. The next stage will be physical spaces which resemble the interpassive consumer monads of MySpace or the IPod (Paul Morley imagines such a space in Words and Music): My, I... what happened to Our Space, or the idea of a public that was not reducible to an aggregate of consumer preferences?

In Ghost Box and Mordant Music, the lost concept of the public has a very palpable presence-in-absence, via samples of public service announcements. (Incidentally one connection between rave and GB/MM is the Prodigy's sampling of thiis kind of announcement on 'Charly'.) Public service announcements - remembered because they could often be disquieting, particularly for children - constitute a kind of reservoir of collective unconscious material. The disinterment of such broadcasts now cannot but play as the demand for a reurn of the very concept of public service. Ghost Box repeatedly invoke public bodies - through names (Belbury Poly, the Advisory Circle) and also forms (the tourist brochure, the textbook). It's no accident that television - with its long-since dishonoured 'public service remit' - is crucial to both them and MM. Mordant oneirically pulp memories from different periods and media into a dreamed past. On Dead Air, 70s television is made to co-exist with rave and electro. Television and rave both stand for modes of collectivity that are either lost or dying, and their combination hints at a kind of collectivity that has never happened.

The public service announcement is of such importance because it is so formally similar to advertising, the most corrosive of postmodern forms. Baudrillard was right (see 'Advertising Degree Zero' in Simulation and Simulacra): advertising has long since exploded beyond its bounds until to consume everything else, implacably coercing all cultural processes (education as well as entertainment) into becoming adverts for themselves.

Confronted with capital's intense semiotic pollution, its encrustation of the urban environment with idiotic sigils and imbecilic slogans no-one - neither the people who wrote them nor those at whom they are aimed - believes, you often wonder: what if all the effort that went into this flashy trash were devoted to a public good? If for no other reason, Ghost Box and Mordant Music are worth treasuring because they make us pose that question with renewed force.

October 24, 2006

Old school

Where to start with Sunday's enthralling - Elektric - Prime Suspect conclusion?

Perhaps with the ending, which, to my great relief, avoided all pyrotechnics; neither the characters nor the complications were sacrificed to the soap opera punctuation mark of the cheap death scene. (This was contrary to media misdirection, which hinted rather heavily that Tennison would not survive...)

If I was unsure about Prime Suspect when it started, that was because of misgivings about Lynda La Plante, whom I've always distrusted for many of the same reasons that I've never been persuaded by Jimmy McGovern. There is always a kind of femachismo in La Plante's writing, a sentimentalization of male homosociality, as if the greatest achievement for a woman would be to be included in a man's world. (It comes as no surprise to learn that La Plante was reportedly sniffy about the direction that the final Prime Suspect ....)

But by the end, Tennison no longer wants to be 'one of the lads'. So in the final scene, she refused the tawdry consolations of easy bonhomie, walking her own - lonely - path, burned out, battered, but unbowed - just herself and the choices that she still affirms: the consummate existentialist.

This was a loneliness denuded of all glamour; not a young man's loneliness, where you can walk off into a sunset, knowing there are many sunsets to come. Knowing also that domesticity and reproduction are not expected of you (and Prime Suspect has always been clear that women have still not escaped those expectations). The hard choices she had to make bite harder as she gets older, now that there are only cheerless entrance halls and not heated arguments with exasperated lovers to come home to, and the whole familiar, familial world points fingers of reproach.

The scenes at the funeral were especially powerful: Tennison heroically rejecting the embrace of the Family, smug sister and smug niece (plummy niece's accent mercilessly mocked by Tennison) proferring reproductive futurism's warm milk, Tennison preferring to drink alone (repulsing, too, the repulsive sexual overtures of an opportunistic barman: 'Take your fucking hand off me.')

Hearth and home were always a temptation, a deflection, and Tennison is resolute in seeing the agents of reproductive futurism as demonic avatars, offering a succour more fake, more deadly even than the bottle. Children would have been an indulgence for Tennison, who had chosen, instead, to clear up the mess produced by other people's children.... And by their parents, whose love, if it is there at all, is both excessive and insufficient (but what is love if it is not an excess, a sickness, and this Prime Suspect suggested that the sickest love of all is that between father and daughter?)

So there is Tennison, pushing her way through other people's children, a 'Zombie Army of teenagers ...'

When Prime Suspect started it could look as if it the structuring opposition was career versus domesticity (very La Plantean/ Thatcherite); but by the end, it was a matter of domesticity versus public duty. And who is going to thank you for choosing public duty, these days? (Thankfully, it turns out that there are some hard won words of thanks at the end, all the more moving for their quieteness, their difficulty, their lack of ceremony. This will have to be enough.)

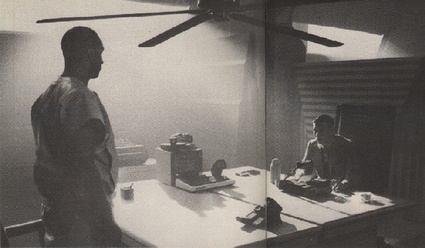

So many shots of Tennison in a lit office, framed by darkness... The public world, receding, rotting ... The streets now a stalking and prowling ground for other people's children, abandoned by absentee parents, long gone or (always) late home...

One of the new Blairite therapeutic-managerialist cops describes Tennison as 'old school'... Yes, in so many ways...

Tennison's existential drama was so consummately drawn that the plot almost became a distraction. You could drown in the nuances in Mirren's expression, her face a crumpled mask over which she exerted painterly control. Now, she is a bewildered old woman hastily covered in a blanket, resurfacing from yet another black-out; now, the ruthless hunter, the steel in the eyes, the spine, the mind, glinting again...

But it wasn't all about Mirren.

Laura Greenwood deserves special credit for her performance as Penny: an incendiary combination of teen rage, wounds, secrets, intelligence, sensitivity. Teenagers, so poorly served by most TV drama, emerged as complex figures for once: the frontline casualties of neo-liberalism's economic experiments, victims and betrayers because betrayed by everyone, beguiling but dangerous in so many ways. One of the themes was adults' vulnerability to teenagers. Most of the adult characters are ruined, compromised, or weakened by their love for teenagers. (They fuck you up...) Not least Tennison herself.... 'She stole my heart...'

This was an exquisite production in every respect. Little details... As Ian put it last week: 'The most touching details ... are also always the smallest, the most prosaic; like the victim's father, needing to go off and just sit in his car, alone, with a can of beer. (If this is true, which we don’t actually know yet. But it *felt* true.)' It did turn out to be true, a credit to the script. This is the kind of detail one often finds in Highsmith, where a character assumes guilt not because their actions are malevolent, but because they are inexplicable, apparently causeless. The strange contingency of desire...

Exceptional use was made of longueurs, the camera lingering on scenes long after the grammar of TV drama has taught us to expect it to depart - a technique that has perhaps been borrowed from comedies like The Office. Sound was crucial here: scratchy fumblings, airconditioner hum, evoking the intertia of the Real....

Into these silences and near-silences, violence, when it erupted, was that much more terrifying...

The perfect ending...

Doubles and doubling everywhere...

(Blackouts)

'You remind me of...'

'You...'

'When I was your age...'

Tennison's double, Penny - the ghost of what she was, become the revenant-revenger of her aborted child. (No-one could have failed to notice that Penny is about the age that Tennison's child would have been if it had not been terminated...)

'How could you kill your child?'

The last stand, between Tennison and reproductive futurism...

But Tennison holds her nerve, yields nothing to reproductive futurism, affirms - though the whole world, family photos on its desk, seems to disagree - that her ethical commitment to public duty was the right choice.

October 19, 2006

Phonograph blues

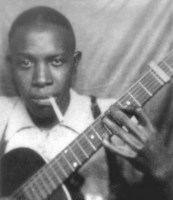

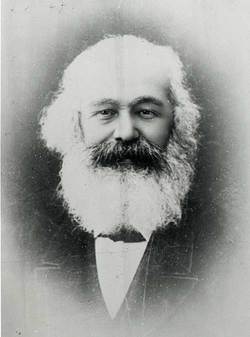

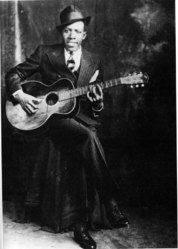

|  | There are only five dates in Johnson's life that can undeniably be used to assign him to a place in history: Monday, November 23; Thursday, November 26; and Friday, November 27, 1936, he was in San Antonio, Texas, at a recording session. Seven months later, on Saturday, June 19 and Sunday, June 20, 1937, he was in Dallas at another session. Everything else about his life is an attempt at reconstruction. As director Martin Scorsese says in his foreword to Alan Greenberg's play 'Love In Vain: A Vision of Robert Johnson', "The thing about Robert Johnson was that he only existed on his records. He was pure legend."- Wikipedia on Robert Johnson | The way that Tricky works – fucking around with sounds on the sampler until his sources are unrecognisable wraiths, ghosts of their former selves; composing music and words spontaneously in the studio; mixing tracks live as they're recorded; retaining the glitches and inspired errors, the hiss and crackle – all this is strikingly akin to early Seventies dubmeisters like King Tubby. - Simon R on Tricky, June 1995 |

Owen's brief comment on blues records a while back says something crucially important about sonic hauntology:

- there's surely no music more utterly dominated by its recording technology than 1930s blues. Listening to Robert Johnson you have, rather than the expected in yr face earthiness and presence, layers upon layers of fizz, crackle, hiss, white noise, as if its been remixed by Basic Channel rather than recorded in a room in some mythologised deep south.

All that needs to be added to this is the idea that the 'mythologized deep south' arises from the 'layers of fizz, crackle, hiss, white noise'; there is no presence except mythologically, no myth without a recording surface which both refers to a (lost) presence and blocks us from attaining it. Rockism could be defined as the quest to eliminate surface noise, to 'return' to a presence which, needless to say, was never there in the first place; hauntology is a coming to terms with the permanence of our (dis)possession, the inevitability of dyschronia.

I repeat, I re-cite: hauntology is the closest thing we have to a movement, a zeitgeist, at the moment (and one of the uncanniest aspects of it is the fact that there seem to be very few lines of explicit influence among the artists involved).

In his crucial piece in the new Wire, Simon backs away from the term 'hauntology' because of its 'post-structuralist baggage'; but that 'baggage' is what gives the term its special purchase; and the fact that the hauntological discontinuum connects with the dyschronic condition which Derrida describes is what makes it more than the 'latest thing'.

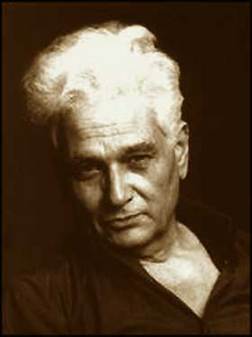

Given that Simon devotes so much of his Wire piece to discussing the end of pop history, it is worth recalling that Derrida wrote Spectres of Marx in part about the 'end of history' thesis then being propounded by Fukuyama. In addition to being Derrida's book on Marx and Marxism, Spectres of Marx can also be read as his engagement with postmodernism. Postmodernism only achieves full-spectrum dominance after 1989, when 'apparently victorious' capitalism thinks it is in a position to declare the end of history. (It's worth noting here that Pop's confident forward motion doesn't long survive the end of the Cold War.) Derrida's title, needless to say, was a play on all of the ghostly imagery in Marx - most notably, of course, the opening line of the Communist Manifesto. 'A spectre is haunting Europe - the spectre of Communism.' Part of the point was: if communism has always been spectral, what does it mean to say that it is now dead?

|  |

Derrida's other major reference plex is Hamlet, especially the line, 'The time is out of joint.' It is this sense of temporal disjuncture that is crucial to hauntology. Hauntology isn't about the return of the past, but about the fact that the origin was already spectral. We live in a time when the past is present, and the present is saturated with the past. Hauntology emerges as a crucial - cultural and political - alternative both to linear history and to postmodernism's permanent revival.

Ten years ago, we would have looked to SF and cyberpunk for this alternative. But hauntology and cyberpunk can now emerge as twins; travelling back in time in Butler's Kindred is the complement of the violent irruption of the past in Morrison's Beloved. It's no accident that hauntology begins in the Black Atlantic, with dub and hip-hop. Time being out of joint is the defining feature of the black Atlantean experience. As Mark Sinker wrote, the 'central fact in Black Science Fiction - self-consciously so named or not - is an acknowledgement that Apocalypse already happened: that (in PE's phrase) Armageddon been in effect.' In this disjunctive time, it makes perfect sense for Terminator X to juxtapose samples of helicopters with discussions about the slave trade, as he does on Apocalypse...91. There is no way in which a trauma on the scale of slavery - 'the holocaust that's still going on' as Chuck D had it - can be incorporated into history, American or otherwise. * It must remain a series of gaps, lost names, screen memories, a hauntology. X marks the spot... The deep, unbearable ache in Kindred arises from the horrible realisation that, for contemporary black America, to wish for the erasure of slavery is to call for the erasure of itself. What to do if the precondition for your being is the abduction, murder and rape of your ancestors?

The trauma that postmodernism screens is the catastrophe of Capital: the terminator of history, there from the beginning distributing microchips to accelerate its advent. Postmodernism is characterised by what Jameson calls the 'nostalgia mode'. Now, it is important to remember that the nostalgia mode is not explictily nostalgic. On the level of content, the productions of the nostalgia mode make no reference to the past at all; yet formally, they are reiterations. Jameson's example is Body Heat, a film given a modern-day setting but which was clearly made according to the formal conventions of 40s noir. Here, there is dyschronia but is disavowed. The exact equivalent of this in pop are Franz Ferdinand and the Arctic Monkeys (I note that hype about the latter seems to be dissipating at an unseemly rate - with any luck they will be this year's Darkness). There is an interesting way in which cultural products that are openly nostalgic cannot belong to the nostalgia mode - precisely because they pointedly raise issues of temporality and historicity which the nostalgia mode must suspend.

Compare Burial to the 'New Rave' for an illustration of the difference between a hankering for the past and the nostalgia mode. Burial implicitly accept that the whole concept of 'New' Rave is a contradiction in terms, that rave posited an endlessly dilated Now eternal, that to 'repeat' rave would not to be to re-iterate it. Far better, to mourn for rave, to point to its absence, than to pretend that it could be re-lived - since re-living was what Rave precisely was not doing. That was what Rave was: an alternative to (Indie) re-living. (Incidentally, it's hard to believe that the Guardian's piece on New Rave - which talks of 'the dark days of 1991-93' when 'it looked like the guitar really was extinct' - isn't a piece of deliberate comedy; it is certainly rockist self-parody, establishing that the Guardian apparently has an infinite pool of buffoons to draw upon when it comes to pop coverage. Who would listen to the Prodigy's 'Charly' and Altern 8 these days, eh? It's only fifteen years ago when such records could be hits but the gap between then and now seems absolute.)

Dyschronia is not repressed in hauntology; it rises to the surface. Or rather, it unsettles the very distinction between surface and depth, between background and foreground. In sonic hauntology, we hear that time is out of joint. The joins are audible - in the crackles, the hiss...

It's no accident that Tricky should keep coming back at the moment, that Ian's groundreaking piece on Tricky in the Wire should have been the first to broker seriously the concept of 'sonic hauntology', that, when I first heard Burial, I would reach for Tricky as a point of comparison, or that as I listen to Stone Cold Ohio I am continually reminded of Maxinquaye. Listen back to 'Aftermath' - with its Blade Runner sample ('Let me tell you about my mother'), and its citations from Japan's 'Ghosts'; it's almost too perfect. Listen, again, to what Ian had to say:

- Is it merely coincidence that the Sylvian quote and the Blade Runner lift converge in the same song? "Ghosts"...Replicants? Electricity has made us all angels. Technology (from psycho-analysis to surveillance) has made us all ghosts. The replicant ("YOUR EYES RESEMBLE MINE...") is a speaking void. The scary thing about ‘Aftermath’ is that it suggests that nowadays WE ALL ARE. Speaking voids, made up only of scraps and citations ... contaminated by other people's memories ... adrift ...

What Little Axe, Burial, Ghost Box, The Caretaker share with Tricky is that they foreground the surface noise. There is no attempt to smooth away the textural discrepancy between the crackly sample and the rest of the recording. This is one reason why hauntology is not just some lazy, hazy term for the ethereal. Hauntology isn't about hoky atmospherics or 'spookiness' but a technological uncanny.

The spectres are textural. The surface noise of the sample unsettles the illusion of presence in at least two ways: first, temporally, by alerting us to the fact that what we are listening to is a phonographic revenant, and second, ontologically, by introducing the technical frame, the unheard material pre-condition of the recording, on the level of content. We're now so accustomed to this violation of ontological hierarchy that it goes unnoticed. But in his Wire piece, Simon refers to the shock he experienced when he first heard records constructed entirely out of samples. I vividly recall the first time I went into studio and heard vocal samples played through a mixing desk; I really do remember saying, 'It's like hearing ghosts...'

(As to the necromantic aspect of sampling: remember that when Keith Leblanc sampled Malcolm X's voice on 'No Sell Out', it was practically regarded as an act of sacrilege at first.)

|  |

Whether or not Robert Johnson really did strike a Faustian bargain, the Gothic dimension of the recording process could not have escaped the imagination of the man who wrote 'Phonograph Blues' and 'Hellhound on my Trail'. What cinema had commented upon and instantiated in films like The Student of Prague - the uncanny presence of the double - Johnson confronted in the encounter with his recorded voice: the part (object) of him which would achieve immortality, returning, buried beneath crackle and hiss, as a phono-doppelganger.

Modernity was built upon 'technologies that made us all ghosts', and postmodernity could be defined as the succumbing of historical time to the spectral time of recording devices. Postmodernity screens out the spectrality, naturalising the uncanniness of the recording apparatuses. Anyone hearing a recording of their own voice or seeing a photograph of themselves is presented with a double. The uncanny thought, often repressed or forgotten, is that the recordings and the photographs will survive us; that as we contemplate them, we are put in the position of a ghost. (It's no surprise that Poe wrote one of the earliest essays on photography. Who knows what he would have made of phonography? One of the interesting things about Skeleton Key, a film of little merit but which has kept coming back to me since I saw it last year, is that the horror is intimately connected with records and recordings.)

It's no accident that Johnson was recording at around the same time as Al Bowlly - that is, at a time when recording technology had developed sufficiently to achieve a kind of sepia effect but not well enough that the audio simulation had become convincing, life-like.

Too high a resolution and we enter the time of the ubiquitous icon, that which is all-too-familiar. The ellipses in Johnson's life - 'there are only five dates in Johnson's life that can undeniably be used to assign him to a place in history' - are another kind of 'hiss' that adds to his mystique, of course. It is as if history never happens; either there are too many gaps, which have to be filled with rumours, supposition and fantasy; or there is an excessive, exhaustive record, so complete as to render the narration of history redundant.

In an excellent summary of hauntology on Dissensus, possibly the clearest and most succinct yet, John Doe refers to 'disinternment - a disinternment of styles, sounds, even techniques and modes of production now abandoned, forgotten or erased by history'. Yet, in sonic hauntology, disinterment goes alongside internment, the deliberate burial of signal behind noise.

What is mourned for most keeningly in the Ghost Box and Mordant Music records, it often seems, is the very possibility of loss. VHS, DVD and multi-channel TV mean that the fugitive evanescence that once used to characterize the watching of television programmes - seen once, and then only remembered - is now gone (think of how the very word 'broadcast' now seems quaint). 70s television was in modernist time; and with Ghost Box, it's difficult to know whether you are dealing with nostalgic modernism or modernist nostalgia, or whether the distinction makes any sense.

The story of Basinski's Disintegration Loops - tapes that destroyed themselves in the transfer to digital - is a parable (again almost too perfect) for the switch from the fragility of analogue to the infinite replicability of digital.

Mordant Music's Dead Air sounds like an electro/rave version of The Disintegration Loops. Mordant are fascinating in part because, as Simon points out in his Wire piece, they affirm decay and deliquescence as productive processes. It is as if the mould growing on the archives is the creative force behind their sound. Listening to Dead Air is like stumbling into an abandoned museum 200 years into the future where old rave tracks play on an endless loop, degrading, becoming more contaminated with each repetition; or like being stranded in deep space, picking up decaying radio signals from a far distant earth to which you will never return; or like memory itself re-imagined as an oneiric television studio, where fondly recalled television announcers, drifting in and out of audibility, narrate your nightmares in reassuring tones.

|  |

There are obvious parallels between Mordant's 'uniquely British tone of despair and decay' and the Burial LP, even if Burial's ghosts are junglist, while Mordant's a more motley bunch. What is compelling in both cases is that the sounds that are being elegiacally de-vived belong to dance music. Dancehalls submerged in hiss.... collective dreams buried....

* Mention of American history brings us back, inevitably, to Greil Marcus. (Before I go on, and for the record, I make, surely unnecessarily, all of the disclaimers about acknowledging Marcus' brilliance etc.) But Ian's original point was more subtle than it is being given credit for. It's not that Marcus' preferences are 'sonically incorrect'; dub is exactly the sort of thing he will claim to like, but which he avoids writing about in any depth. The suspicion must be that the evasion of dub (and rap) is more than a matter of contingency, it is constitutive. I think this is evident by posing a simple question: where is production in Marcus's writing? References to producers - or production techniques - in Marcus are, at best, fleeting. There is a very definite metaphysics of presence at work in his writing. For all the alleged disjunctures of Lipstick Traces, it ultimately centres not only on the Pistols, but a Pistols' live performance. The unlive, dubbled aspect of pop is what Marcus represses, consistently: why Gang of Four and not the Pop Group, why do Joy Division merit only a passing mention but the Clash and Costello get page after page, why are the Slits celebrated until they are ... produced (by Dennis Bovell)?

It is this perpetually deferred encounter with the technological uncanny which means that, no amount of using the words 'weird' or talking about old records, will necessarily give Marcus a take on hauntology. I haven't read any of Marcus' Old Weird America material, so correct me if I'm wrong - isn't it about Dylan? - but couldn't all this return to field recordings be fitted, all-too-comfortably, into a quest for presence? I haven't read any of the new one, either, but The Voice of American Prophecy has metaphysics of presence written all over it. The whole reterritorialization on American history could also be read as a repression of the Black Atlantic, but that's another story.

My 'frighteningly in-depth' On-U Sound round-up is now up on the Fact website.

|  |

In other news - I'm also speaking at this on Saturday if anyone wants to come....

By now it's overkill, but...

Special feature on the Scarface DVD featuring (amongst many others) Russell Simmons, Raekwon, Method Man, Snoop, Big Boi, Andre 3000, and Puff Daddy who describes it as 'the most important film of our generation...'

October 18, 2006

New blogs for old

Paul, ex of Autonomic for the People, has a new blog here...

Philip, not entirely ex of It's All in Your Mind, has a new blog here...

Dejan doesn't have a new blog, but he has some new things to say on B D-P.

October 16, 2006

Up until now, I've never been entirely convinced by Prime Suspect but, credit where its due, the latest - and last - installment is absolutely superb.

I'm sure Helen Mirren is outstanding as the Queen - I must confess, I have no urgent desire to go and see what must turn out to be de facto monarchist propaganda (whose message would have to be: deep down, the Queen is a human being, just like us) - but I doubt that her performance could better this. One line on her face is more expressive than most thesps' whole careers. A look, a faint change of expression is enough to carry the unbearable weight of Prime Suspect 7's great theme, mortality. Mortality threatens Mirren's Jane Tennison in many forms: her age (at one point, she sees herself in the mirror and seems unable recognise herself, an increasingly common experience as one gets older), doubts about wrong choices (the reproaches of empty hallways, address books full of names that she cannot call when in need of succour), the death of her father (the scenes with Frank Finlay, also excellent, imply a lifetime of evasions, frustrations and inadequately handled affections). There were at least three moments that provoked tears, and not cheaply.

I was never convinced by Cracker either - I always thought it too pleased with itself, Fitz's 'shocking psychological insights' amounting to shopworn Catholic nihilism - and when it returned for a special two weeks ago, all my misgivings were confirmed. The 'political' points were rather too easy, depending upon a plot that lacked any credibility; and Fitz's alcoholism and gambling, as ever, were rather too picturesque. The alcoholism in the latest Prime Suspect, by contrast, is squalid, an embarrassment , not some machismo vice of which one is (not so) secretly proud.

Alcohol, in fact, seems to be the poisoned lifeblood of Prime Suspect 7's England; characters are either accusing each other of being alcoholic or pouring themselves a glass, unremarked and unobserved. The England that emerges here - a place of modernist architecture, miserable hospital wards, Alcoholic Anonymous meetings, lonely late night coffee bars - resembles the banal inferno grimly painted in Lumet's The Offence or in the novels of David Peace. For once, London's ready made dystopia is used rather than glossed over. But there is a terrible beauty in the photography, an understated expressionistic stylishness brilliantly shown off in the last few moments, in a bravura sequence that alternated between shots of passing trains, slow motion footage and the unblinking monochrome of CCTV. Let's hope that the second, and concluding, part maintains the standard when it airs next week.

October 15, 2006

Family values

- In 2002 Mr Bush lumped Iraq, North Korea and Iran together in an “axis of evil” and said he would stop them acquiring nuclear weapons. He implied that regime change in Iraq might be followed by regime change in North Korea and Iran. Now one says it has the bomb and the other is ignoring Security Council orders to stop enriching uranium. The anti-proliferation policy Mr Bush put at the forefront of his foreign policy has been a colossal failure.

- The Economist this week

- My definition of winning is killing so many of our foes that their children rue the day their fathers took up arms against us. Would I torture a suspect myself? Absolutely if the choice was between saving American lives or saving my honor, my honor would fly out of the door. Why, because I know how much I love my children and the parents of those soldiers I saved love them just as much. Perhaps I would live in shame for the rest of my life but it is a small price for saving even one of my country-men’s lives.

- Pierre Legrand's Pink Flamingo Bar (subtitle: 'A common man looks at the war on Islamic terror'), 'Moral Preening regarding torture, idealism with someone else’s family is such an ugly thing'

- [P]olitics .. remains at its core, conservative, insofar as it works to affirm a structure, to authenticate social order, which it then intends to transmit to the future in the form of its inner Child. That Child remains the perpetual horizon of every political intervention. ... What ... would it signify not to be "fighting for our children"? .. [F]ascism of the baby's face encourages parents ... to join in a rousing chorus of "Tomorrow Belongs to Me"...

- Lee Edelman, No Future:Queer Theory and the Death Drive

October 14, 2006

IP OTM

As this source tells us:

- 'SCARFACE: THE WORLD IS YOURS has an interesting premise: what if gangster Tony Montana survived the explosive gun battle at the end of the movie? Starting from this key scene, the game dives into an alternate storyline featuring Tony and his quest to reclaim his underworld empire and set himself up as Miami’s greatest drug lord. Players will control Tony and help him rebuild his drug contacts and gain the loyalty of gang members. They have all of Miami to explore and control by setting up drug trades, avoiding rival gangs, and taking over territory.'

Also:

October 03, 2006

Hauntological blues

- Dub messes big time with such notions of uncorrupted temporality. Wearing a dubble face, neither future nor past, Dub is simultaneously a past and future trace: of music as both memory or futurity, authentic emotion and technological parasitism. Ian Penman, '[the Phantoms of] TRICKNOLOGY [versus a Politics of Authenticity]'

Since we're talking about hauntology, we ought to have mentioned Beloved by now: not only Morrison's novel, but also Demme's astonishing film. It's telling that Demme is celebrated for his silly grand guignol, The Silence of the Lambs, while Beloved is forgotten, repressed, screened out. Hopkins' pantomime ham turn as Lecter surely spooks no-one , whereas Thandie Newton's automaton-stiff, innocent-malevolent performance as Beloved is almost unberable: grotesque, disturbing, moving in equal measure.

Like The Shining - a film that was also widely dismissed for nigh on a decade - Beloved reminds us that America, with its anxious hankerings after an 'innocence' it can never give up on, is haunted by haunting itself. If there are ghosts, then what was supposed to be a New Beginning, a clean break, turns out to be a repetition, the same old story. The ghosts were meant to have been left in the Old World .... but here they are...

Whereas The Shining digs beneath the hauntological structure of the American family and finds an Indian Burial Ground, Beloved pitches us right into the atrocious heart of America's other genocide: slavery and its aftermath. No doubt the film's commercial failure was in part due to the fact that the wounds are too raw, the ghosts too Real. When you leave the cinema, there is no escape from these spectres, these apparitions of a Real which will not go away but which cannot be faced. Some IMDB viewers complain that Beloved should have been reclassifed as Horror... well, so should American history...

Beloved comes to mind often as I listen to Stone Cold Ohio, the outstanding new LP by Little Axe. Little Axe have been releasing records for over a decade now, but, in the 90s, my nervous system amped up by jungle's crazed accelerations, I wasn't ready to be seduced by their lugubrious dub blues. In 2006, however, the haunted bayous of Stone Cold Ohio take their place alongside Burial's phantom-stalked South London and Ghost Box's abandoned television channels in hauntological Now. Since I received Stone Cold Ohio last week, I've listened to listen else; and when I wasn't immersed in Stone Cold Ohio I was re-visiting the other four Little Axe LPs. The combination of skin-tingling voices (some original, some sampled) with dub space and drift is deeply addictive. Little Axe's world is entrancing, vivid, often harrowing; it's easy to get lost in these thickets and fogs, these phantom plantations built on casual cruelty, these makeshift churches that nurtured collective dreams of escape...

Shepherds...

Do you hear the lambs are crying?

Little Axe's records are wracked with collective grief. Spectral harmonicas resemble howling wolves; echoes linger like wounds that will never heal; the voices of the living harmonise with the voices of the dead in songs thick with reproach, recrimination and the hunger for redemption. Yet utopian longings also stir in the fetid swamps and unmarked graveyards; there are moments of unbowed defiance and fugitive joy here too.

I know my name is written in the Kingdom....

Little Axe is Skip McDonald's project. Through his involvement with the likes of Ohio Players, the Sugarhill Gang and Mark Stewart, McDonald has always been associated with future-orientated pop. If Little Axe appear at first sight to be a retreat from full-on future shock - McDonald returning to his first encounter with music, when he learned blues on his father's guitar - we are not dealing here the familiar, tiresome story of a 'mature' disavowal of modernism in the name of a re-treading of Trad form. In fact, Little Axe's anachronistic temporality can be seen as yet another rendering of future shock; except that this time, it is the vast unassimilable trauma, the SF catastrophe, of slavery that is being confronted. (Perhaps it always was...)

Even though Little Axe are apt to be described as 'updating the blues for the 21st century' they could equally be seen as downdating the 21st century into the early 20th. Their dyschronia is reminiscent of those moments in Stephen King's It where old photographs come to (a kind of) life, and there is a hallucinatory suspension of sequentiality. Or, better, to the time slips in Octavia Butler's Kindred, where contemporary characters are abducted back into the waking nightmare of slavery. (The point being: the nightmare never really ended...)

There is no doubt that blues has a privileged position in pop's metaphysics of presence: the image of the singer-songwriter alone with his guitar provides rockism with its emblem of authenticity and authorship. But Little Axe's return to the supposed beginnings unsettles this by showing that there were ghosts at the origin. Hauntology is the proper temporal mode for a history made up of gaps, erased names and sudden abductions. The traces of gospel, spirituals and blues out of which Stone Cold Ohio is assembled are not the relics of a lost presence, but the fragments of a time permanently out of joint. These musics were vast collective works of mourning and melancholia. Little Axe confront American history as a single 'empire of crime', where the War on Terror decried on Stone Cold Ohio's opening track - a post 9/11 re-channeling of Blind Willie Johnson's 'If I had My Way' - is continuous with the terrordome of slavery.

When I interviewed Skip last week for Fact, he emphasised that Little Axe tracks always begins with the samples. The origin is out of joint. He has described before the anachronizing Method-ology he uses to transport himself into the past. 'I like to surf time. What I like to do is study time-periods - get right in to 'em, so deep it gets real heavy in there.' McDonald's deep immersion in old music allows him to travel back in time and the ghosts to move forward. It is a kind of possession (recalling Winfrey's claim that she and the cast were 'possessed' when they were making Beloved). The capacity to allow yourself to be possessed is the mark of all great performers.* Little Axe's records skilfully mystify questions of authorship and attribution, origination and repetition. It is difficult to disentangle sampling from songwriting, impossible to draw firm lines between a cover version and an original song. Songs are texturally-dense palimpsests, accreted rather than authored. McDonald's own vocals, by turns doleful, quietly enraged and affirmatory, are often doubled as well as dubbed. They and the modern instrumentation repeatedly sink into grainy sepia and misty trails of reverb, falling into a dyschronic contemporeanity with the crackly samples.

Ian's recent tilt at Greil Marcus echoes the misgivings he expressed in his landmark piece on Tricky (the piece, really, in which Sonic Hauntology was first broached). There, Ian complained about Marcus' 'measured humanism which leaves little room for the UNCANNY in music'. Part of the reason Little Axe are intriguing is that their use of dub makes it possible for us to encounter blues as uncanny and untimely again. Little Axe position blues not as part of American history, as Marcus does, but as one corner of the Black Atlantic. What makes the combination of blues and dub far more than a gimmick is that there is an uncanny logic behind the superimposition of two corners of the Black Atlantic over one another.

Adrian Sherwood's role in the band is crucial. Sherwood has said that Little Axe take inspiration from the thought that there is a common ground to be found in 'the music of Captain Beefheart and Prince Far I, King Tubby and Jimi Hendrix'. In the wrong hands, a syncresis like this could end up as a recipe for stodgy, Whole Earth humanism. But Sherwood is a designer of OtherWorld music, an expert in eeriness, a kind of anti-Jools Holland . What is most pernicious about Holland is the way in which, under his stewardship, pop is de-artificialized, re-naturalized, blokily traced back to a facialized source. Dub, evidently, goes in exactly the opposite direction - it estranges the voice, or points up the voice's inherent strangeness. When I interviewed Sherwood last week he was delighted by my description of his art as 'schizophonic' - Sherwood detaches sounds from sources, or at least occults the relationship between the two. The tyranny of Holland's Later... has corresponded with the rise of no-nonsense pop which suppresses the role of recording and production. But 'Dub was a breakthrough because the seam of its recording was turned inside out for us to hear and exult in; when we had been used to the "re" of recording being repressed, recessed, as though it really were just a re-presentation of something that already existed in its own right.' (Penman)

Hence what I have called dubtraction; and what is subtracted, first of all, is presence. Chion refers to the voice that is detached from a source as acousmatic. The dub producer, then, is an acousmatician, a manipulator of sonic phantoms that have been detached from live bodies. Dub time is unlive, and the producer's necromantic role - his raising of the dead - is doubled by his treating of the living as if dead. For Little Axe, as for the bluesmen and the Jamaican singers and players they channel, hauntology is a political gesture: a sign that the dead will not be silenced.

I'm a prisoner

Somehow I will be free

Hauntological addenda

It's no accident that Ian's remarks on hauntology were prompted by Tricky, and who - as Ian mentions - should have helped produce Maxinquaye if not Mark Stewart?

Another hauntological On-U connection is African Headcharge. The African Headcharge LPs are masterpieces of OtherWorld music: eerie, abstract slices of rhythmic psychedelia. Sherwood came up with the concept of African Headcharge after hearing Eno remark that My Life in the Bush of Ghosts was intended to be a 'vision of a psychedelic Africa'. Sherwood has completed a new African Headcharge LP and its title will be ... Vision of a Psychdelic Africa.

*And exactly what someone like Robbie Williams, and this is the pathology of his postmodernism, is unable to do; he is always falling over himself to advertise his apes and japes as citations, over which his majesty the Ego prevails.

My On-U piece, which includes interviews with Skip McDonald, Adrian Sherwood and Mark Stewart, will be appearing very soon on the Fact website.

Little Axe are playing an acoustic set at Ray's Jazz in Foyle's bookshop, Charing Cross Road, next Monday, 9th October, at 6 PM. Admission free.

October 02, 2006

Postmodernism as Pathology

Ian P is tremendous on Scarface, but I'm not being perverse when I say that, oddly, Scarface is the one major De Palma film that has never particularly moved me, even though I buy everything Ian has to say about its - massive - cultural significance. In fact, it may be because Scarface is too flat with hip-hop, Cribs, gangster chic, that it has left me cold. Gangsta is one of capitalist realism's 'myth of no myths': a myth which presents itself as an exposure and undercutting of fantasy, a biological reduction. As Ian so memorably puts it: '"Is this it? Fuckin, suckin, snortin..." is not just American Dream cynical, it approaches Beckett in its existential fault-line ennui! Is this it? Breathin', eatin, shittin...?'

Ian argues that De Palma is like Hitchcock without the psychopathology. But De Palma's relationship to Hitchcock was itself psychopathological; his films openly staged revivalism as necrophilia. De Palma didn't pay homage to the Master, he stalked him, relentlessly, unable to escape his fixation. At this point I would link to my post on Obsession from the old blogger site (a post that was prompted last time IP and I had a to-and-fro about D-P), but that's all but impossible now that the site has been hacked by corporate interests. So I present it again below, in a slightly remixed form, partly as a prompt - to myself - to write more about De Palma; partly because I hope that it might inspire Bacterial grl, who I know is also fascinated by D-P, to post something on him.

- De Palma remakes Vertigo at least twice: in Body Double and, in what for me is his masterpiece, the appropriately-titled Obsession . His mugging of Hitchcock, his rearrangement of the Master's entrails, is not even close to being subtle. But there's an intriguing implex here: Vertigo - itself, needless to say, a study of obsession/ possession - becomes the object of an obsession, the object of Obsession.

Like the later Body Double , Obsession has a glutinous, heavy, slow-motion feel; it seems to be filmed almost entirely as a dream sequence. (That is what partly what makes Body Double , which ought to be just trash , queasily compelling: it is unreal, patently so, but that unreality has an odd consistency, the consistency of an involuntary private fantasy, and you're kept watching this film about voyeurism by the guilty suspicion that you are voyeurising De Palma.)

Obsession is filmed in a cloying soft-focus, as if it is not only a dream, but a memory (a memory of a dream), as if what is happening is happening in a fatal (No) time, a deja-vu time in which everything that happens is being repeated even as it ostensibly happens for the first time. Vertigo , again. Deja vu: the already seen .

In Scotty's search for a lost, never-present, referent, in his consciousness of the weight of a past one falsifies even as one attempts to re-inhabit it, in his amour fou-driven passion for remaking , De Palma finds an allegory for the postmodern predicament (his own). And ours?

Itself a remake, Obsession is also, fittingly and inevitably, about remaking.

It stars Cliff Robertson, an ageing Southern aristocrat out of Poe, near-paralysed by melancholia. Robertson, we learn, lost his wife and daughter in a bungled kidnap years ago. The police told him not to pay the kidnappers, to fill a suitcase with blank pieces of paper. And that is the appalling, crippling weight he bears now: he chose the money over his family. Money undergoes a negative cathexis, becomes meaningless, or even abhorrent, to him. The fact he has it means that he does not have his wife (Genevieve Bujold) and child.

The image of the young Robertson, the plan to outwit the kidnappers failed/ foiled, the case open, the worthless pieces of paper fluttering in the wind, is an image of total loss: because he dared not risk losing something valuable, he has lost the ability to find value in anything ....

And then, years later, on a convalescent business trip to Italy (his whole life, now, is a kind of failed convalescence, a deathly enduring ) he sees - can it be - a double of his dead wife. Naturally, something awakens in him - Scotty's hopeless hope - a hope born in denial, born in the refusal of the unconscious to believe in death (or time). Can it be? - yet it is impossible, surely, because this is an image of his wife, not as she would be now, but exactly as she looked then .

And he finds that this doppelganger is working on - yes, naturally - a restoration (of a local church). She faces a dilemma: beneath one of the frescoes there is another painting. It could be a great lost masterpiece or it could be --- nothing. Should she risk destroying the fresco for the sake of what might only be a daub?

It goes without saying that this dilemma is doubled in Robertson's: should he investigate, dig deeper, at the risk of ---- destroying this young woman ----- or, worse, as far as he is concerned, destroying his image of her?

And so the film unwinds, (I won't spoil it for those who haven't seen it) towards its climax, which like the end of the first two thirds of Vertigo , amounts to a re-running of the past, an exposure of a plot, the anatomy of a betrayal. Unlike Vertigo , though, Obsession , improbably, ends happily - but it is a vertiginous, disturbing, distinctly creepy, happy ending... Bujold and Robertson spinning round and round and round each other, gripping each other's hands....