April 26, 2006

Reports from the neo-liberal lab

'FE has been a kind of neo-liberal lab in which reforms that will be implemented in the rest of education have been tried out first...' My piece on Further Education is in Socialist Worker this week.

April 25, 2006

Dis-identity politics

The discussion of V for Vendetta - on Pinocchio Theory in particular - has been far more interesting than the film deserved. Yes, there is a certain frission in seeing a major Hollywood movie refusing to unequivocally condemn terrorism, but the political analysis in the film (as in the original comic) is really rather threadbare. That is Moore's fault; it can't be blamed on the Wachowskis. Like all of Moore's work, V for Vendetta is considerably less than the sum of its parts. I've complained before of finding Moore's continual efforts to reassure himself and his readers of their erudition - every time you are about to succumb to the fictional world, it's as if Moore taps you on your shoulder and say, 'We're too good for this, aren't we folks?' - highly distracting and irritating.

As for V for Vendetta's politics - apart from the subjective destitution scenes, they amount in large part to the familiar populist ideology which maintains that the world is controlled by a corrupt oligarchy that could be overthrown if only people knew about it. Steven says that 'rather than trying to please all demographics, [the film] identifies a deeply religious, homophobic, ultra-”patriotic,” imperialistic surveillance state as the source of oppression'. But isn't this precisely 'appealing to all demographics', since few homophobic fascists will identify themselves as homophobic fascists, and it's hard to imagine anyone warming to Hurt's foaming-at-the-mouth ranter, still less voting for him. Postmodern fascism is a disavowed fascism (cue the BNP leaflet delivered through my door when I lived in Bromley, photograph of a smiling kiddywink, slogan: 'My daddy's not a fascist'), just as homophobia survives as disavowed homophobia. The strategy is to refuse the identification while pursuing the political programme. 'We of course deplore fascism and homophobia, but...' The Wachowskis' government bans the Koran, but that is the last thing that Blair and Bush would ever do; no, they will praise Islam as a 'great religion of peace' while bombing Muslims. Blair's authoritarian populism is far more sinister than V for Vendetta's pantomime autocracy precisely because Blair is so successful at 'presenting himself as the reasonable, honest bloke on the side of the common man'. Similarly, Bush's linguistic incompetence, far from being an impediment to his success, has been crucial to it, since it has allowed him to pose as a 'man of the people', belying his privileged Harvard and Yale-educated background. It is significant in fact that class is not mentioned at all in the film. As Jameson wryly notes in 'Marx's Purloined Letter', it is not 'particularly surprising that the system should have a vested interest in distorting the categories whereby we think class and in foregrounding gender and race, which are far more amenable to liberal ideal solutions (in other words, solutions that satisfy the demands of ideology, it being understood that in concrete social life the problems remain equally intractable).'

The climactic scenes of V for Vendetta, in which the people rise up (by this time, against no-one) made me think, not of some great political Event, but rather of the Make Poverty History campaign - a 'protest' with which no-one could possibly disagree. The comparison with Fight Club does V for Vendetta no favours; the targets of Tyler Durdon's terrorism were not the fusty symbols of the political class but the franchise coffee bars and skyscrapers of impersonal capital.

I'm no fan of the Wachowskis' Matrix, but it succeeded in two ways that V for Vendetta never will. The Matrix has become a massively propagated pulp mythos (whereas who but academics will think about the V for Vendetta film a year from now? It'll be a year after that until academics recognize that the far more fascinating and sophisticated Basic Instinct II is worthy of study). More importantly, it suggested that what counts as 'real' is an eminently political question.

That ontological dimension in what is missing from the progressive populist model, in which the masses cannot but appear as a dupes, fooled by the lies of the elite but ready to effectuate change the moment they are made aware of the truth. The reality, of course, is that the 'masses' are under few illusions about the ruling elite (if anyone is credulous about politicians and 'capitalist parliamentarianism', it is the middle classes). The Subject Supposed Not To Know is a figure of populist fantasies - more than that: the duped subject awaiting factual enlightenment is the presupposition on which progressive populism rests. If the most crucial political task is to enlighten the masses about the venality of the ruling class, then the preferred mode of discourse will be denunciation. Yet, this repeats rather than challenges the logic of the liberal order; it is no accident that the Mail and the Express favour the same denunciatory mode. Attacks on politicians tend to reinforce the atmosphere of diffuse cynicism upon which capitalist realism feeds. What is needed is not more empirical evidence of the evils of the ruling class but a belief on the part of the subordinate class that what they think or say matters; that they are the only effective agents of change.

This returns us to the question of reflexive impotence. Class power has always depended on a kind of reflexive impotence, with the subordinate class's beliefs about its own incapacity for action reinforcing that very condition. It would, of course, be grotesque to blame the subordinate class for their subordination; but to ignore the role that their complicity with the existing order plays in a self-fulfilling circuit would, ironically, be to deny their power.

'[C]lass consciousness,' Jameson observes in 'Marx's Purloined Letter', 'turns first and foremost around the question of subalternity, that is around the experience of inferiority. This means that the 'lower classes' carry around within their heads unconscious convictions as to the superiority of hegemonic or ruling-class expressions or values, which they equally transgress and repudiate in ritualistic (and socially and politically ineffective) ways.' There is a way, then, in which inferiority is less class consciousness than class unconsciousness, less about experience than about an unthought precondition of experience. Inferiority is in this sense an ontological hypothesis that is not susceptible to any empirical refutation. Confronted with evidence of the incompetence or corruption of the ruling class, you will still feel that, nevertheless, they must possess some agalma, some secret treasure, that confers upon them the right to occupy the position of dominance.

Enough has been already been written about the kind of class displacement people like myself have experienced. Dennis Potter's Nigel Barton plays remain perhaps the most vivid anatomies of the loneliness and agony experienced by those who have been projected out of the confining, comforting fatalism of the working class community and into the incomprehensible, abhorrently seductive rituals of the privileged world. 'A drive from nowhere leaves you in the cold,' as the Asscociates sang in 'Club Country'. 'Every breath you breathe belongs to someone there.'

There is a Cartesian paradox about such experiences, in that they are significant only because they produce a distanciation from experience as such; after undergoing them, it is no longer to conceive of experience as some natural or primitive ontological category. Class, previously a background assumption, suddenly interposes itself - not so much as a site for heroic struggle, but as a whole menagerie of minor shames, embarrassments and resentments. What had been taken for granted is suddenly revealed to be a contingent structure, producing certain effects (and affects). Nevertheless, that structure is tenacious; the assumption of inferiority constitutes something like a core programming which makes sense of the world in advance. To think of oneself as capable of doing a 'professional' job, for instance, requires a traumatic shift in perspective, and if there are confidence crises and nervous breakdowns, they will be very often the consequence of the core programming intermittently reasserting itself.

The real lesson to draw from Potter's Barton plays is not the fatalist-heroic one about the agonies of the charismatic individual confronting intransigent social structures. The plays have to be read instead against class-as-ethnicity and for class-as-structure; in any case, as they make clear, the occult machineries of social structure produce the visible ethnicities of language, behaviour and cultural expectations. The plays' demand is not for a re-acceptance into the rejecting community, nor a full accession into the elite, but for a mode of collectivity yet to come.

Potter's challenges to naturalism then, become far more than mere PoMo trickery. His foregrounding of the way in which fictions structure reality, and of the role that television itself plays in this process, brings to the fore all the ontological issues that worthier, more traditional social realist writers conceal or distort. There is no realism, Potter suggests, beyond the Real of class antagonism.

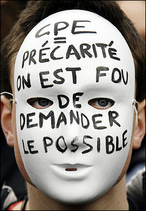

Now is perhaps the time to address two good questions that Bat mailed in response to the reflexive impotence post. First, Bat asked, is the situation for French teenagers different from that of their British counterparts? This is easily dealt with, since, after all, it was the very problem with which the post aimed to deal. French students are far more embedded in a Fordist/ disciplinary framework than are British students. In education and employment, the disciplinary structures survive in France, providing some contrast with, and resistance to, the cyberspatial pleasure matrix. (For reasons I will explore in more depth shortly, this is not necessarily for the best, however.) Bat's second question raised more important issues; doesn't talking about reflexive impotence reinforce the very interpassive nihilism it supposedly condemns? I would say that the exact opposite is the case. I've had more mail about the reflexive impotence post than any other; mostly, actually, from teenagers and students who recognize the condition but who, far from being further depressed by seeing it analysed, find its identification inspiring. There are very good Spinozist and Althusserian reasons for this - seeing the network of cause-and-effect in which we are enchained is already freedom. By contrast, what is depressing is the implacable poptimism of the official culture, forever exhorting us to be excited about the latest dreary-shiny cultural product and hectoring us for failing to be sufficiently positive. A certain 'vulgar Deleuzianism', preaching against any kind of negativity, provides the theology for this compulsory excitation, evangelizing on the endless delights available if only we consume harder. But what it is so often inspiring - in politics as much as in popular culture - is the capacity to nihilate present conditions. The nihilative slogan is neither be 'things are good, there is no need for change', nor 'things are bad, they cannot change', but 'things are bad, therefore they must change.'

This brings us to subjective destitution, which, unlike Steve Shaviro, I think is a precondition of any revolutionary action. The scenes of Evey's subjective destitution in V for Vendetta are the only ones which had any real political charge. For that reason, they were the only scenes which produced any real discomfort; the rest of the film does little to upset the liberal sensibilities which we all carry around with us. The liberal programme articulates itself not only through the logic of rights, but also, crucially, through the notion of identity, and V is attacking both Evey's rights and her identity. Steve says that you can't will subjective destitution. I, however, would say that you can only will it, since it is the existential choice in its purest form. Subjective destitution is not something that happens in any straightforward empirical sense; it is, rather, an Event precisely in the sense of being an incorporeal transformation, an ontological reframing to which you must assent. Evey's choice is between defending her (old) identity - which, naturally, also amounts to a defence of the ontological framework which conferred that identity upon her - and affirming the evacuation of all previous identifications. What this brings out with real clarity is the opposition between liberal identity politics and proletarian dis-identity politics. Identity politics seeks respect and recognition from the master class; dis-identity politics seeks the dissolution of the classifactory apparatus itself.

That is why British students are, potentially, far more likely to be agents of revolutionary change than are their French counterparts. The depressive, totally dislocated from the world, is in a better position to undergo subjective destitution than someone who thinks that there is some home within the current order that can still be preserved and defended. Whether on a psychiatric ward, or prescription-drugged into zombie oblivion in their own domestic environment, the millions who have suffered massive mental damage under capitalism - the decommisioned Fordist robots now on incapacity benefit as well as the reserve army of the unemployed who have never worked - might well turn out to be the next revolutionary class. They really do have nothing to lose...

______________________________________________________________

Dominic Fox writes:

'Dennis Potter lived just down the road from me in Ross-on-Wye, where I

spent my teens. I mean literally down the road: you could just about

see his house from mine. Not that one ever saw Potter himself, who was

somewhat of a recluse.

"To think of oneself as capable of doing a 'professional' job, for

instance, requires a traumatic shift in perspective, and if there are

confidence crises and nervous breakdowns, they will be very often the

consequence of the core programming intermittently reasserting

itself."

Potter's own autobiographical sketch in "Occupying Powers" (the James

MacTaggart Memorial Lecture he gave in 1993, most famous for his

characterisation of Birt and Hussey as "croak-voiced daleks") includes

IIRC the comment that his psoriasis (and depression) flared up -

cripplingly - at just the moment when the ambitious, eager young

Oxford graduate was about to embark on a Barton-style career in

politics himself.

I'm sure one could recruit Potter to the cause of Militant Dysphoria...'

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Reader Leigh Phillips poses some interesting questions:

'I wonder if it is true that 'British students are, potentially, far more likely to be agents of revolutionary change than are their French counterparts. The depressive, totally dislocated from the world, is in a better position to undergo subjective destitution than someone who thinks that there is some home within the current order that can still be preserved and defended'. This seems to me to be little more than an example of the 'hungry belly theory of revolution', that is to say, the more fucked up things are, the better they are. There are two quick things to say against this. One, no one knows precisely what event or circumstance ultimately acts as the revolutionary catalyst - the French students' erstwhile forebears, the 68 generation, kicked off events at the tale end of a period of unprecedented distribution of wealth (the post-war keynesian consensus). Meanwhile, citizens of many countries in Africa are simply so fucked - have such hungry bellies - that mere survival comes before abstract thoughts of resistance. Two, defence of social gains - even if those gains result in the co-optation of resistance/exhaustion of revolutionary energy - as the French students are doing, is, in advance of 'The Glorious Day', if there ever is one, A Good Thing in itself. Otherwise, one is reduced to consciously voting for the most reactionary option possible in the hope that ever greater oppression and exploitation will ultimately result in resistance/revolution. This itself is a re-expression of the substitutionist ideology of 'V' you rightly criticise, for it is still a form of 'waking up' the ignorant masses.'

Some quick answers:

1. The students I am talking about are not necessarily economically 'hungry'. What they suffer from is an existential impoverishment. The issue is not objective at all - objectively, they live in one of the wealthiest countries of the world - but subjective (in the existentialist sense).

2. The French situation is not a social gain. At best, it has avoided a social loss. But as I've argued before, the immobilization model plays into the hands of the capitalist realism by implying that the only alternatives to neo-liberal policies are backward-looking.

3. The masses are not 'ignorant', but they do need waking up from the depressive trance of reflexive impotence. It is not knowledge they lack, but belief.

April 21, 2006

Marking time

A number of half-completed posts have been held up by my having to deal with the redundancy issue and with the reflexive impotents. But posts on Nigel Cooke, the Gothic Nightmares exhibition and class and subjective destitution should appear very early next week.

In the meantime, my interview with Julian House is in the current issue of Fact magazine, available free from many record shops in the UK.

I'm going to the East coast for the weekend; I may very well write a post about that when I return. I'll leave you with a quote from 'The Purloined Marx', Jameson's 1995 essay on Specters of Marx:

'Capitalism... as in the historical narrative we have inherited from the triumphant bourgeoisie and the great bourgeois revolutions, is the first social form to have eliminated religion as such and to have entered on the purely secular vocation of human life and human society. Yet according to Marx, religion knows an immediate 'return of the repressed' at the very moment of the coming into being of such a secular society, which, imagining it has done away with the sacred, then at once unconsciously sets itself in pursuit of the 'fetishism of commodities'. The incoherence is resolved if only we understand that a truly secular society is yet to come, lies in the future...'

April 16, 2006

Dub housing

I'm trying to write about something else, I'm trying to listen to something else, but at the moment, it's all about Burial. The interview at Blackdown only adds to the intrigue ('It’s good to have girls liking it'; 'there’s no ‘musicianship’ in my sound, that’s the enemy of my tunes'). It's Burial's ability to hold these two things together - the modernist rejection of 'music' and the drive to reconnect with a female audience - which goes some way to accounting for why his sound is so overpoweringly seductive. And also why it is a genuine inheritor of dub science. As I argue on Dissensus: 'the best dub always has a relationship to a certain sweetness of (the) Song. The white take-up of dub has often seemed to think that you can make dub more intense by entirely removing those elements and simply turning up the bass. A parallel error was made in jungle, when the inhuman-feminine cheesey rave elements were stripped out and you ended up with the rigor mortis of techstep. Course the point is that the bass sounds all the more powerful BY CONTRAST with those sweet elments (and the Song sounds all the more plaintive, all the more affecting for being disappeared in front of our ears - that's why the best dub is literally sublime).'

Autonomic for the People shares my enthusiasm, with a brilliant post that also forms part of the growing discussion about Burial Dissensus. I.T.: 'it just does sound like south London, from the seagulls to the reverberating car stereos to the mad muttering of psych-wards patients on day-release.'

Partly, it's the uncanniness of listening to a sound that so perfectly captures the feeling of the streets in which one lives that makes the LP so madly compelling. (But it's not as if it only reverberates for London listeners; for Autonomic, 'it's vividly reminiscent of growing up in Winnipeg near the train yards, and hearing their horns and screeches wafting for miles through the thick summer air.') In any case, it's starting to feel like Burial is the most important album since Dizzee's debut. But while Dizzee's sound was ultra-dry, all brittle percussion and harshly angular electronics, Burial's sound is smeary, blurred; and while Dizzee's depression was unmistakeably teenage in its orgins, Burial's sadness belongs to someone older. I'm reminded of Joy Division, not only because of the new-dawn-fades dreams-always-end mood, but also because of the way in which the production recalls Hannet's:

Autonomic on Burial: 'It reminds me of a car purposefully moving through a cold wet city night while a passenger stares, heart-in-throat, out the back window, remembering places and people as they pass.'

Jon Savage on Unknown Pleasures, 1979: 'Joy Division's spatial circular themes and Marint Hannett's shiny, waking dream production gloss are a perfect reflection of Manchester's dark spaces and empty places: endless sodium lights and semis seen from a speeding car, vacant industrial sites - the endless detritus of the 19th century - seen gaping like teeth from an orange bus.'

April 14, 2006

Parish Announcements

1. Owen brilliant on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. I've had this album for two decades, but Owen has made me hear it in a completely new way. Worth comparing with Cabaret Voltaire's Voice of America and Red Mecca, and Front 242's later 'Funkghadafi', the latter shamelessly and openly mining the mystique of the 'terrorist Other' for 'pure sensation'. The Eno/ political line is fascinating, and worthy of further investigation. I wonder how Eno's later advocacy of Rortian pragmatism (which he opposed, pointedly, to 'fundamentalism') connects with Bush of Ghosts' exoticization of Islam, and how both connect to his current anti-war stance. Also check out Owen's new space ('for fragments, the flagrantly unfinished, frippery of various kinds, links, polemics, pretty pictures, complaints about one's health and things with similar lack of rigour').

2. Three stunning posts by Dominic Fox. Militant dysphoria may be precisely the concept I was gesturing towards with my vague notion of 'positive disengagement'. In their paper at the Zizek conference in Oxford last week, Lorenza Chiesa and Alberto Toscano quoted what could well become the militant dysphoriacs' motto: 'Enough with Hedone, we want Agape!'

3. Interesting parallel responses to the Reflexive Impotence post:

Mountain 7: 'Reflexive Impotence and Depressive Hedonia – ‘an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure’ – reopens the perspective on what some of us were witnessing at the time of this injuncture:

Blank response, an arrogant monied acceptance of the costs of higher education, organized action lacking the menace of violence that (as our French counterparts have shown) is almost always necessary to genuine protest.

Contrast. Frenzied excitement that greeted the opening of yet another aspirational bar. All plastic sheen, posturing and almost suicidal excess of alcohol.'

Blissblog: 'Trader Joe's--a Whole Foods-style chain of markets with delicious, healthful, incredibly cheap produce (nuts, coffee, wine, etc) plus prepared meals and budget-gourmet stuff (salsas, pasta sauces, etc) -recently opened to much fanfare in New York, and on the opening day there were queues round the block, people waiting hours to be admitted into what is at the end of the day a supermarket! It seemed weird--possibly a sign of the times--that the kind of anticipation/excitement once motivated by the release of an epochal album -- Sgt Pepper’s, or in more recent years the new Radiohead or new Oasis album (when they were at their phoney-Beatlemania peak) would now be motivated by the prospect of organic cashews and Fair Trade Costa Rica coffee.'

4. Meanwhile, Bat sends me a link to a BBC story saying that 'Goths are more likely to self-harm'. This interestingly compares with the Guardian piece I.T. linked to a while back which argued that 'goths make the best pupils'. Both of these claims - Goths self-harm; Goths are the best students - square with my experience. It fits: both education and self-harm lie beyond the pleasure principle, and finding enjoyment beyond hedone is more than ever likely to make you an outsider. Most of the Goths I teach are voracious readers who have serious political commitments. The other significant exceptions to the depressive hedonic rule, by the way, are black Christians.

5. Everyone in London interested in theory should try to make this:

'Alain Badiou, Being and Event

A book launch with Oliver Feltham, Justin Clemens and Alberto Toscano

To celebrate the recent publication by Continuum books of Alain Badiou's 1988 magnum opus L'Etre et l'evenement, CSISP (Centre for the Study of Invention and Social Process) will host a round-table and discussion between the book's translator, Oliver Feltham, and two scholars of Badiou's work, who will collectively try to introduce some of the book's principal themes - being as multiplicity, the idea of the generic, the naming of the event, the difference between presentation and representation.

Thursday 27th April

2.00-6.00pm

Venue to be confirmed

A reception will follow the discussion at 6pm

The event is free but please register in advance at savonarola@hotmail.co.uk'

London after the rave

'From the moment that human beings started communicating with electrical and electromagnetic signals, the ether has been a spooky place. Four years after Samuel Morse strung up his first telegraph wire in 1844, two young girls in upstate New York kick-started Spiritualism, a massively popular occult religion which attempted to fuse science and seance. [...]

Now, you may think that this ghoulish dial-tweaking has gone the way of the dousing rod, but electromagnetic spiritualism is alive and well [...]. Today aficionados call it Electronic Voice Phenomena, or EVP. [...]

Interestingly, one of the most important requirements for good EVP is the presence of noise: a distorted channel, interference, echo, superimposition. In other words, all the active elements of our current hip-hop/dub mixology are designed to receive these spectral messages. No wonder the stuff can put you into another world.'

- Erik Davis, Dead Machines: A review of The Ghost Orchid and electromagnetic voice phenomena

A MASSIVE new addition to the sonic hauntology canon: the self-titled album by Burial on Kode 9's Hyperdub label.

Burial is the kind of album I've dreamt of for years; literally. It is oneiric dance music, a collection of the 'dreamed songs' Ian Penman imagined in his epochal piece on Tricky's Maxinquaye. Maxinquaye would be a reference point here, as would Pole - like both these artists, Burial conjures audio-spectres out of crackle, foregrounding rather than repressing sound's accidental materialities. Tricky and Pole's 'cracklology' was a further development of dub's materialist sorcery in which 'the seam of its recording was turned inside out for us to hear and exult in; when we had been used to the "re" of recording being repressed, recessed, as though it really were just a re-presentation of something that already existed in its own right' (Penman). But rather than the hydroponic heat of Tricky's Bristol or the dank caverns of Pole's Berlin, Burial's sound evokes what the press release calls a 'near future South London underwater. You can never tell if the crackle is the burning static off pirate radio, or the tropical downpour of the submerged city out of the window.'

Near future, maybe... But listening to Burial as I walk through damp and drizzly South London streets in this abortive Spring, it strikes me that the LP is very London Now - which is to say, it suggests a city haunted not only by the past but by lost futures. It seems to have less to do with a near future than with the tantalising ache of a future just out of reach.

It's interesting to compare the LP with the forthcoming EP on kin by Johnny Dark (see my press release here). Johnny's Toronto-based 'nu-step' is a kind of science fictional what-if exercise; what if the late 90s London 2-step inhuman-feminine sound had continued to mutate without devolving into the sullen dead ends of grime and dubstep? The ultra-exuberance of Johnny's sound - 'garish rather than grimy' - contrasts starkly with the mournful restraint of the Burial album. Instead of the 'can't wait' of 2-step's anorgasmic anticipation-plateau, Burial is haunted by what once was, what could have been, and - most keeningly - what could still happen. Johnny's sound has all the freshness of newly sprayed graffiti; the Burial LP is like the faded ten year-old tag of a kid whose rave dreams have been crushed by a series of dead end job.

Burial is an elegy for the hardcore continuum, a Memories from the Haunted Ballroom for the rave generation. It is like walking into the abadoned spaces once carnivalized by raves and finding them returned to depopulated dereliction. Muted air horns flare like the ghosts of raves past. Broken glass cracks underfoot. MDMA flashbacks bring London to unlife in the way that hallucinogens brought demons crawling out of the subways in Jacob's Ladder's New York. Audio hallucinations transform the city's rhythms into inorganic beings, more dejected than malign. You see faces in the clouds and hear voices in the crackle. What you momentarily thought was muffled bass turns out only to be the rumbling of tube trains.

Burial's mourning and melancholia sets it apart from dubstep's emotional autism and austerity. My problem with dubstep has been that in constituting dub as a positive entity, with no relation to the Song or to Pop, it has too often missed the spectrality wrought by dub's subtraction-in-process. The emptying out has tended to produce not space but an oppressive, claustrophobic flatness. If, by contrast, Burial's schizophonic hauntology has a 3D depth of field it is in part because of the way it grants a privileged role to voices under erasure, returning to dub's phono-decrentism. (Penman again - Dub 'makes of the Voice not a self-possession but a dispossession - a "re" possession by the studio, detoured through the hidden circuits of the recording console.') Snatches of plaintive vocal skitter through the tracks like fragments of abandoned love letters blowing through streets blighted by an unnamed catastrophe. The effect is as heartbreakingly poignant as the long tracking shot in Tarkovsky's Stalker that lingers over sublime objects-become trash.

Burial's London is a wounded city, populated by ectsasy casualties on day release from psychiatric units, disappointed lovers on night buses, parents who can't quite bring themselves to sell their rave 12 inches at a carboot sale, all of them with haunted looks on their faces, but also haunting their interpassively nihilist kids with the thought that things weren't always like this. The sadness in the Dem 2 meets Vini Reilly-era Durutti Column 'You Hurt Me' and 'Gutted' is almost overwhelming. 'Southern Comfort' only deadens the pain. Ravers have become deadbeats, and Burial's beats are accordingly undead - like the tik-tok of an off-kilter metronome in an abandoned Silent Hill school, the klak-klak of graffiti-splashed ghost trains idling in sidings. 10 years ago, Kodwo compared the 'harsh, roaring noise' of No U-Turn's 'hoover bass' with like the sound of a thousand car alarms going off simultaneously'. The subdued bass on Burial is the spectral echo of a roar, burned-out cars remembering the noise they once made.

Burial reminds me, actually, of paintings by Nigel Cooke currently on show, appropriately enough, at the South London Gallery in Camberwell. I'll be writing more about Cooke's paintings over the next few days, but the morose figures Cooke graffitis onto his own paintings are perfect visual analogues for Burial's sound. A decade ago, jungle and hip hop invoked devils, demons and angels. Burial's sound , however, summons the 'chain-smoking plants and sobbing vegetables' that sigh longingly in Cooke's painting. Speaking at the Tate last week, Cooke observed that much of the violence of grafitti comes from its velocity. There's something of an affinity between the way that Cooke re-creates grafitti in the 'slow' medium of oil paints and the way in which Burial submerge (dubmerge?) rave's hyperkinesis in a stately melancholia.

Burial's dilapidated Afro NoFuturism does for London in the 00s what Wu Tang did for New York in the 90s. It delivers what Massive Attack promised but never really achieved. It's everything that Goldie's Timeless ought to have been. It's the Dub City counterpart to Luomo's Vocalcity. Imagine a spectralized Gorrilaz on downers, but a tenth as smug and ten times as evocative. Burial is one of the albums of the decade. Trust me.

April 11, 2006

Reflexive impotence

|  |

Why are French students out on the streets rejecting neo-liberalism, while British students, whose situation is incomparably worse, resigned to their fate? The answer to that question is partly, also, an answer to why a group like the Arctic Monkeys connect with British teenagers. It is a matter not of apathy, nor of cynicism, but of reflexive impotence.

It is reflexive impotence that you hear in the Arctic Monkeys - yes, they know things are bad, but more than that, they know they can't do anything about it. But that 'knowledge', that reflexivity, is not a passive observation of an already existing state of affairs. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy. And guess what? They probably know that too.

Reflexive impotence amounts to an unstated worldview amongst the British young. Many of the teenagers I work with have mental health problems or learning difficulties. Depression is endemic. The number of students who have some variant of dyslexia is astonishing. It is not an exaggeration to say that being a teenager in late capitalist Britain is now close to being reclassified as a sickness. This pathologization already forecloses any possibility of politicization. By privatizing problems - treating them as if they were caused only by the individual's neurology and/ or family background - any question of social systemic causation is ruled out.

Part of the success of neo-liberalism has consisted in its presenting of capitalism as 'purely economic', as if the the 'mental health plague' and the routine disintegration of families have nothing whatsoever to do with capitalist 'creative destruction'. Mental health, in fact, is a paradigm case of how Capitalist Realism operates. Capitalist Realism insists on treating mental health as if it were a natural fact, like weather (but, then again, we know that even weather is no longer a natural fact). Poor mental health is of course a massive source of revenue for multinational drugs companies. You pay for a cure from the very system that made you sick in the first place.

The majority of students I encounter seem to be in a state of what I'd call depressive hedonia. Depression is usually characterised in terms of anhedonia, but the state I'm referring to is constituted not by an inability to get pleasure so much as it by an inability to do anything else except pursue pleasure. There is a sense that 'something is missing' - but no appreciation that this mysterious, missing enjoyment can only be accessed beyond the pleasure principle. In large part this is a consequence of students' ambiguous structural position, stranded between their old role as subjects of disciplinary institutions and their new status as consumers of services.

In his crucial essay 'Postscript on Societies of Control', Deleuze distinguishes between the disciplinary societies described by Foucault, which were organized around the enclosed spaces of the factory, the school and the prison, and the new control societies, in which all institutions are embedded in a dispersed corporation. According to Deleuze, the factory-school-prison system was an expression of the nineteenth century 'capitalism of concentration'. With this in mind, CCRU once described schools as 'concentration camps', spaces in which bodies were confined, subdued and forced to concentrate.

Walk into almost any class at the college where I teach and you will immediately appreciate that you are in a post-disciplinary framework. Foucault painstakingly enumerated the way in which discipline was installed through the imposition of rigid body postures. During lessons at our college, however, students will be found slumped on desk, talking almost constantly, snacking incessantly (or even, on occasions, eating full meals). The old disciplinary segmentation of time is breaking down. The carceral regime of discipline is being eroded by the technologies of control, with their systems of perpetual consumption and continuous development.

The 'market Stalinist' funding system and the parlous state of the college finances means that the college literally cannot afford to exclude students, even if it wanted to. The lack of an effective disciplinary system has not, to say the least, been compensated for by an increase in student self-motivation. Students are aware that if they don't show up for weeks on end, and/ or if they don't produce any work, they will not face any meaningful sanction. They typically respond to this freedom not by pursuing projects but by falling into hedonic (or anhedonic) lassitude: the soft narcosis, the simstim eternity, the comfort food oblivion of Playstation, all-night TV and marijuana. Capital's interpassive nihilism.

Ask students to read for more than a couple of sentences and many - and these are A-level students mind you - will protest that they can't do it. The most frequent complaint teachers hear is that it's boring. It is not so much the content of the written material that is at issue here; it is the act of reading itself that is deemed to be 'boring'. What we are facing here is not just time-honoured teenage torpor, but the mismatch between a post-literate 'New Flesh' that is 'too wired to concentrate' and the confining, concentrational logics of decaying disciplinary systems.

There is a sense, of course, in which reading is boring. Upon first encounter, philosophical or literary writing which is genuninely new will be frustrating and difficult. But that is true of the acquisition of any skill - learning to play a musical instrument, for instance, is demanding before it is enjoyable. A certain hedonic-conservative consensus holds sway, however, which holds, with Homer Simpson, that 'if something is too hard to do, then it's not worth doing'.

On this account, 'boring' is not opposed to 'interesting'. To be bored simply means to be removed from the communicative sensation-stimulus matrix of texting, MTV and fast food, to be denied, for a moment, the constant flow of sugary gratification on demand. Some students want Nietzsche in the same way that they want a hamburger; they fail to grasp - and the logic of the consumer system encourages this misapprehension - that the indigestibility, the difficulty is Nietzsche.

An illustration. I challenged one student about why he always wore headphones in class. He replied that it didn't matter, because he wasn't actually playing any music. In another lesson, he was playing music at very low volume through the headphones, without wearing them. When I asked him to switch it off, he replied that 'even he couldn't hear it'. Why wear the headphones without playing music or play music without wearing the headphones? Because the presence of the phones on the ears or the knowledge that the music is playing (even if he couldn't hear it) was a reassurance that the matrix was still there, within reach. The use of headphones is significant here - Pop is experienced not as something which could have impacts upon public space, but as a retreat into private OedIpod consumer bliss, a walling up against the social.

The consequence of being hooked into the entertainment matrix is twitchy, agitated interpassivity, an inability to concentrate or focus. Students' incapacity to connect current lack of focus with future failure, their inability to synthesize time into any coherent narrative, is symptomatic of more than mere demotivation. It is, in fact, eerily reminiscent of Jameson's analysis in 'Postmodernism and Consumer Society'. Jameson observed there that Lacan's theory of schizophrenia offered a 'suggestive aesthetic model' for understanding the fragmenting of subjectivity in the face of the emerging entertainment-industrial complex. 'With the breakdown of the signifying chain' Jameson summarised, 'the Lacanian schizophrenic is reduced to an experience of pure material signifiers, or, in other words, a series of pure and unrelated presents in time. ' Jameson was writing in the late 1980s - i.e. the period in which most of my students were born. What we in the classroom are now facing is a generation born into that ahistorical, anti-mnemic blip culture - a generation, that is to say, for whom time has always come ready-cut into digital micro-slices.

If the figure of discipline was the worker-prisoner, the figure of control is the debtor-addict. Cyberspatial capital operates by addicting its users; Gibson recognized that in Neuromancer when he had Case and the other cyberspace cowboys feeling insects-under-the-skin strung out when they unplugged from the matrix (Case's amphetamine habit is plainly the substitute for an addiction to a far more abstract speed).

If, then, something like Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder is a pathology, it is a pathology of late capitalism - a consequence of being wired into the entertainment-control circuits of hypermediated consumer culture. Similarly, what is called dyslexia may in many cases amount to a post-lexia. Teenagers process capital's image-dense data very effectively without any need to read - slogan-recognition is sufficient to navigate the net-tabloid-magazine informational plane. 'Writing has never been capitalism's thing. Capitalism is profoundly illiterate,' Deleuze and Guattari argued in Anti-Oedipus. 'Electric language does not go by way of the voice or writing: data processing does without them both.' Hence the reason why many successful business people are dyslexic (but is there post-lexical efficiency a cause or effect of their success?)

Teachers are now put under intolerable pressure to mediate between the post-literate schizo-subjectivity of the late capitalist consumer and the demands of the disciplinary regime (to pass examinations etc). This is one way in which education, far from being in some ivory tower safely inured from the 'real world', is the engine room of the reproduction of social reality, directly confronting the inconsistencies of the capitalist social field.

Teachers are often exasperated at students for their failure to see that, if they do not attend classes, or do any reading or thinking at home, then they will not pass the exams. But our mistake is in supposing that all students care about passing exams. Many don't. Many are at college not because of their own ambitions, but because of their parents'. Attending college, or rather, sporadically attending college, sustains their parents' fantasies (that their offspring will all become lawyers and doctors), leaving students free to nurture their fantasies (of ascending, effort-free, into the ranks of celebritydom).

It is worth stressing that none of the students I teach have any legal obligation to be at college. They could leave if they wanted to. But the lack of any meaningful employment opportunities, together with cynical encouragement from government means that college seems to be the easier, safer option. Deleuze says that control societies are based on debt rather than enclosure; but there is a way in which the current education system both indebts and encloses students. Pay for your own exploitation, the logic insists - get into debt so you can get the same McJob you could have walked into if you'd left school at 16 ...

What many students most want from college, although they would never admit it, is an authority structure. There is a demand for an authority which they can then reject; they want to be told what to do, so they can disobey. It is a textbook case of bad faith, a flight from freedom. Interpassive nihilism again.

Teachers are caught between being faciltitator-entertainers and disciplinarian-authoritarians. Teachers want to help students to pass the exams; they want us to be authority figures who tell them what to do. Teachers being interpellated by students as authority figures exacerbates the 'boredom' problem, since isn't anything that comes from the place of authority a priori boring?

Ironically, the role of disciplinarian is demanded of educators more than ever at precisely the time when disciplinary structures are breaking down in institutions. With families buckling under the pressure of capitalism, teachers are now increasingly required to act as surrogate parents, instilling the most basic behavioural protocols in students and providing pastoral and emotional support for teenagers who are in some cases barely socialised.

What, then, are the possibilities for politicization now? On the face of it, the situation is bleak. Jameson observed that 'the breakdown of temporality suddenly releases [the] present of time from all the activities and intentionalities that might focus it and make it a space of praxis'. But nostalgia for the context in which the old types of praxis operated is plainly useless. The French model - which amounts to a demand to retain the Fordist/disciplinary regime - could not work here. Fordism has definitively collapsed in Britain, and with it the efficacy of the old politics. At the end of the control essay, Deleuze wonders what new forms an anti-control politics might take:

'One of the most important questions will concern the ineptitude of the unions: tied to the whole of their history of struggle against the disciplines or within the spaces of enclosure, will they be able to adapt themselves or will they give way to new forms of resistance against the societies of control? Can we already grasp the rough outlines of the coming forms, capable of threatening the joys of marketing? Many young people strangely boast of being "motivated"; they re-request apprenticeships and permanent training. It's up to them to discover what they're being made to serve, just as their elders discovered, not without difficulty, the telos of the disciplines.'

What must be discovered is a way out the motivation/ demotivation binary, so that disidentification from the control program registers as something other than dejected apathy. A positive disengagement, in other words, involving forms of collective activity which break down the OedIpod solitude of the entertainment-consumer.

April 06, 2006

'Even when she tells the truth, it's a lie'

'Catherine is older in this film and the situations are different – she’s challenging the whole psychoanalytic system...' MadeinAtlantis.com

'Heck, even the way she wears her clothes is fascinating. Her costume designer has given her a series of line-straddling outfits. At one point, one hand is gloved and the other ungloved, and several of her dresses feature one clothed shoulder and one bare.

It's as if the costumer is telling us Catherine is both a heroine and a villain. Or that the movie is both very bad and very good.' - Chris Hewitt (St. Paul Pioneer Press )

What happened to David Cronenberg? Wasn’t he attached to direct this film at one point?

Sharon Stone: You know, we love him, of course. He’s so talented and so amazing, and how great was “Crash”? Ohmygod. He is the most gentle, interesting, intelligent, sophisticated person and one of my most things—it’s a little private thing but I’ll share it with you—Marty Scorsese wanted to see “Crash” so I made a surprise dinner party for him and invited David Cronenberg over to the house and screened the movie. Oh, what a fun night! You know, that was a biggie. He had really great ideas, but that would have been a very different kind of movie. I think that in the end, people just got kind of afraid that maybe it wouldn’t be so commercial, because, not to say that some of his ideas didn’t remain in the movie because they did, but what’s funny enough is that some of his ideas that they were the most afraid of remained in the movie. - Melissa Walters

Basic Instinct: a film with this many bad reviews must have something going for it...

|  |

'Basic Instinct' was a poor title for the first film, but it is clear - within seconds - that it is spectacularly inappropriate for the sequel, which glories in the fact that, far from being 'basic' or 'instinctual', human sexuality is always mediated through fantasy, fashion, technology and social role. The proposed but abandoned subtitle, 'Risk Addiction', would have been much better, but you do wonder why they didn't go the whole hog and call it Death Drive.

The film wastes no time in immersing us in preposterous excess. Its opening scene - auto-erotic in the double, Ballardian sense - sees Sharon Stone's Catherine Tramell pleasuring herself, using the ketamined-out Stan Collymore* as meat puppet sex aid, while she drives a Spyker C8 Laviolette at 120 m.p.h. through the heart of London. You conclude, even before the Spyker speeds off the road and into the Thames, leaving the bewildered Collymore to drown, that this must be some kind of dream sequence or drug delirium. When the next scene - in which Stone is interviewed by flatfooted British cops as incredulous as we in the audience are - makes it clear that, no, what you have just seen belongs to what the film is pleased to call reality, you have to ask yourself a question: what kind of a diegesis is it that expects us to treat a scene like that as realistic? The answer is a ridiculous-sublime delirial commodity porn confection of Bond, Ballard, Baudrillard and Bataille.

Basic Instinct 2 is camp, not because it takes itself too seriously, nor because it sends itself up, but because we are not sure quite how seriously it wants us to take it. Reviewer Chris Hewitt wrote that Stone 'knows Basic Instinct 2 is a comedy, and she is the only one in on the joke', but this isn't quite true. When I saw the film, in Leicester Square - an experience that was already vertiginous enough, since much of the action takes place in streets a few hundred yards away from where the cinema is located - the audience seemed quite prepared to laugh at more or less every line, but weren't sure if they were supposed to. There were many times when an isolated laugh cued others to join in, partly from relief, because they now knew, or thought they knew, how they were expected to respond.

I mean, what are you supposed to do when Tramell proclaims, with a perfectly straight face, 'Don't feel too bad ... even Oedipus didn't see his mother coming'?

Basic Instinct 2 is an uneasy experience because, although it is hyper-reflexive to the point where it is hard to think of one character, one scene, one plot twist that isn't a reference or an echo, there is nothing knowing about it. No matter how absurd the film gets, it refuses to raise its eyebrows. It flouts the cardinal rule of PoMo by keeping faith with fantasy. Fantasy, after all, is the ridiculous-sublime - that which, even when we are fully aware of its absurdity, does not relinquish its hold on us.

|  |

Basic Instinct was a mediocre reworking of the postmodern noir template established in Body Heat, notable only for the then unprecedented (in mainstream cinema) explicitness of the sex and for the icy assurance of Stone's performance as Tramell. Verhoeven cast her because she resembled Kim Novak in Vertigo. But, with Tramell, there wasn't a 'real' Judy behind the cool blond facade as there was with Novak's Madeleine; nor was there a male figure constructing the Tramell persona to entrap other males. Tramell was her own construction, a facade without an interior, cruelty withouth instrumentality.

The real enigma of the first film did concern the banal question of whether Tramell was a killer or not, but the nature of the desire driving the movie. It was posed in the infamous leg-crossing scene; was this a female fantasy of a woman subduing men with her sexuality and her confidence, or was it a male fantasy of abasement before a dominatrix? Stone gave the Tramell character a depthless invulnerability, a crystalline poise; her trademark expression a sneer-smile, expressing open contempt for those who desired her. Stone's advance on the Kathleen Turner character in Body Heat (and even over the Linda Fiorentino character in The Last Seduction, which wouldn't come out until 94, two years after Basic Instinct) was her libidinal inscrutability; she wasn't using her sexuality as a means to an end, she was just using it. She presented men with 'the horror of nothing to see', the vacancy of what they desired, knowing that they couldn't stop hallucinating a depth that she didn't even pretend was there.

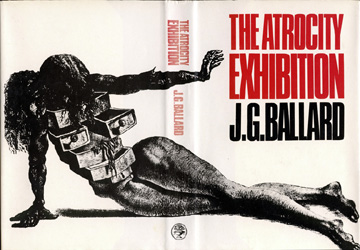

|  |

Tramell returns in the second film as a camp vamp whose persona owes more to Ballard than to film noir. Catherine is a name Ballard has often used, and Basic Instinct 2 sometimes feels that it is as much a sequel to Crash as to Verhoeven's film. Setting the film in a phantasmatic, cybergothic London means, in fact, that Basic Instinct 2 recalls aspects of Ballard's novel that Cronenberg's film, with its North American setting, didn't get to. There was little in the San Franciso of Basic Instinct - all late night bars and ocean-side drives - which would have been unfamiliar to Humphrey Bogart. But the London of Basic Instinct 2 is something we have only imagined when reading The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash. It is a London with all of the 'picture postcard' landmarks - Big Ben, Tower Bridge - erased, and presided over by Foster's phallic Swiss Re building. In addition to Foster's 'gherkin', production designer Norman Garwood - who 'wanted to champion the amazing new architecture that’s emerged in the city over the last 10 years and blend it with the classical, established London' - used the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, the Old Billingsgate Market, County Hall on the South Bank, Imperial College, the Tanaka Business School, and the 'Gothic style' Royal Holloway college as the components of his Baudelaire-meets-Baudrillard hyperreal urban phantasmogoria.

|  |

Roger Ebert, one of the few critics to admit to have enjoyed Basic Instinct 2 ('I cannot recommend the movie, but ... why the hell can't I? Just because it's godawful? What kind of reason is that for staying away from a movie?'), savoured 'the icy abstraction of the modern architecture, which made the people look like they came with the building': a very Ballardian effect. The characters, such as they are, have no more depth than the buildings they move through or the clothes they wear. Stone's wardrobe and jewellery - assembled by long-time Gus Van Sant associate Beatrix Aruna Pasztor - is certainly far more important than anything she says, the clothes far less off-the-peg than the character. Reviewers who complained about the reliance on nudity or sex weren't paying attention. The film is much more about what Stone wears that what she doesn't. Stone herself missed the point when she complained, in the run-up to the film, about the way in which the studio had cut explicit scenes. 'Everything interesting begins in the mind', goes the film's tagline, and Basic Instinct 2 would have been far more courageous if there had been no meat sex whatsoever, if the relationship between Stone and her therapist, Dr Glass (David Morrissey) had taken place entirely through roleplay and fantasy. The meat sex, as ever, is crushingly disappointing. Where the sex is interesting, it is about playing with the Other, watching the Other watching you, recounting fantasies of the Other's fantasies...

'How very Lacanian', as Charlotte Rampling says at one point.

No, really....

|  |

Both of the Basic Instinct films faced the difficulty of restoring a frission to sex in an age when its easy availability renders it banal. The solution was to re-invent the constraints that give sex its allure. Thus the hero-dupe of the first film was a cop invesigating Tramell, and in the second one it is a therapist treating her - the demands of social role magically transforming the eminently attainable Tramell into the lustrous Forbidden Object. The stiff and proper Morrissey is far better in the role of man wrestling with his professional ethics than the sleazy Michael Douglas ever was (who could doubt, even for a moment, that 'sex addict' Douglas would give in to temptation and sleep with the suspect?)

The question of what desire is driving the film is never far away. The thriller genre has always played upon the very familiar fear that we may know very little about those with whom we are most intimate, but in Basic Instinct 2 the unknowability of Others - and more, the unknowability of our own self as Other (i.e. the unconscious) - means that all the narrative elements assume a kind of superpositional hyper-instability. Nothing is resolved, or resolvable - we are in a world where everything can be reassessed or reframed at any moment: the world, that is, of ultra-precarious cybercapital, whose endlessly weaving digital labyrinths resemble the dreamwork itself. When you watch Basic Instinct 2, it is as if you are watching capital itself dream. The fantasies of the characters, the characters as fantasies, are like freefloating deliria unmoored from any individual psychological location. Tramell snares Morrissey's therapist by claiming that she fears that her fantasies are making the murders happen. But is it her thoughts which are 'omnipotent' or is she herself a commodity fetish avatar from Glass's libidinal economy? Tramell even suggests this latter possibility to him: 'Perhaps I am acting out your unconscious desires'. As the film converges with Tramell's 'grotesquely bad' fiction, Basic Instinct 2 comes to resemble Carpenter's In the Mouth of Madness, with Tramell playing a thriller-writer equivalent to the schizo-plague-propagating Horror novelist Sutter Cane. It is almost as if Tramell is a dominatrix-manipulator at an ontological as well as a diegetic level, the Author-God commingling with her characters. But by the end, when she is acting less as a character than as a narrator-commentator, it is clear that even she doesn't know what has happened.

* Collymore, for those who don't know, was a very gifted footballer who ended his career as a sportsmen at a self-destructively premature stage. Since he has ceased playing, Collymore has been exposed in a 'dogging' scandal. In the film, he plays a disgraced footballer who dies having a kind of sex in a car. Hyper-real enough for you?

April 02, 2006

Against immobilization, against nomadology

|  |

The Economist's response to the unrest in Paris is entirely predictable and intermittently hilarious but contains some points that need to be addressed.

On Friday, in a paradigmatic statement of neo-liberal ideology, the Economist repeated the acerbic observation it had already made (at least twice) in its previous edition. Whereas the events of Paris 68 were progressive and forward looking, it argued, the events in Paris 06 are reactionary and conservative.

'Certainly the students who kicked off the latest protests seemed to think they were re-enacting the events of May 1968 their parents sprang on Charles de Gaulle, it wrote in its lead article. They have borrowed its slogans (“Beneath the cobblestones, the beach!”) and hijacked its symbols (the Sorbonne university). In this sense, the revolt appears to be the natural sequel to last autumn's suburban riots, which prompted the government to impose a state of emergency. Then it was the jobless, ethnic underclass that rebelled against a system that excluded them.

Yet the striking feature of the latest protest movement is that this time the rebellious forces are on the side of conservatism. Unlike the rioting youths in the banlieues, the objective of the students and public-sector trade unions is to prevent change, and to keep France the way it is. Indeed, according to one astonishing poll, three-quarters of young French people today would like to become civil servants, and mostly because that would mean “a job for life”.'

A follow-up article in the print edition approvingly quotes Daniel Cohn-Bendit: 'Today's protests are based on the defensive, the fear of insecurity and change'. (What could be a more perfect illustration of Zizek's point in his recent LRB piece that 'liberal communists' - more on which shortly - love 68?)

That the Economist finds it 'astonishing' that 75% of the young French would want to work in the civil service (what? rather than in an EXCITING and FULFILLING career like branding! or marketing!) is more than a little amusing. As is its describing as 'startling' the results of another poll in which '71% of Americans, 66% of the British and 65% of Germans agreed that the free market was the best system available, [whereas] the number in France was just 36%'. And isn't it astonishing that, in France, 'left-leaning intellectuals, with a romantic communist heritage, are not derided but treated as national treasures. There is a lingering culture of suspicion of profit [no! m k-p], and a demonisation of business leaders, encouraged by a mainstream left that [for shame!] equates efficiency with injustice.'

The killer line, the very credo of Capitalist realism - try to read it while keeping a straight face - is this one: 'It is true that the forces of global capitalism are not always benign, but nobody has yet found a better way of creating and spreading prosperity.'

The Economist goes on to engage in some sneering at the 'hypocritical French'. It argues that the 'French' are less 'immobile' than they like to appear. 'Take a closer a look at what [the French] do rather than what they say ... When EDF was floated, over 5m French individuals snapped up the chance to become a shareholder. Vandals near the Sorbonne smashed the glass front of a McDonald's restaurant during the student protests, yet the French remain calm about eating 'le Happy Meal' with their children, and many students work their part-time. Indeed, the American group recently reported strong operating profit for the fourth quarter of 2005 based partly on its huge success in France... The French, it seems, condemn capitalism during office hours, but are quite happy to consume its products at the weekend.' Secondly, it goes on to argue, much of the French opposition to globalization takes place in the name of nationalist protectionism. For example, the Villepin-led government intervened when the French private company Suez faced a hostile bid from an Italian company, but there was no public concern when BNP Paribas acquired an Italian bank, or when L'Oreal bought Body Shop.

No doubt the statistics are selective, the examples hastily generalized to support a stereotyped image of insular French reactivity. Nevertheless, the Economist does highlight some of the problems that the left should have with unequivocally supporting 'immobilization'. It goes without saying that not all of what is happening in France can be characterized in terms of 'immobilization', but it is worth emphasising that an anti-capitalism articulated solely in terms of curbing or containing capitalism cannot be adequate.

For one thing, such a position it is too defeatist, too limited in its ambitions. It's striking how the practice of many of the immobilizers is a kind of inversion of that of the 'liberal communists'. Both assume that there is an irreducible core of capitalism which cannot be eradicated. It is either a case of opposing capitalism in the workplace but consuming its products in your 'free' time (the immobolistes), or fully identifying with capitalism in the workplace while protesting against it and/ or giving to charity in your free time (the Sorosites/ the Chabertistas). And as Padraig points out, there is another brand of liberal socialism, or philanthropic neo-liberalism: BoBonoism, which maintains that fully identifying with capitalism (or the 'right kind' of capitalism) as both a worker and a consumer is already, immediately, ethical. It is Bono, rather than Soros or Gates, who is the real inheritor of Smith. In one of its leaders last year, the Economist decried corporate attempts to fund ethical projects on the grounds that 'wealth creation' is immediately in and of itself ethical, which was Smith's point. Soros thinks that the intervention of a visible hand (his own) is still required to offset the effects of capitalism; Bono believes that capitalism can be reformed such that no offsetting will be needed. Kant argued that the 'Summum Bonum' or 'Highest Good' would be 'virtue crowned with happiness', but that this was impossible on earth and could only be guaranteed by God in the afterlife. 'Summum Bonoism' (there is a supreme good and it is Bono), on the other hand, is a kind of capitalist theology, with Bono and Saint Bob as its beatified advocates, which assumes that there will soon come a time when acquisitiveness and ethical responsibility will be one and the same.

In any case, if anti-capitalism is equated with 'immobilization', not only will it prove ineffective, it will actually serve as part of the ideological framework of Capitalism, much as the Soviet Union used to. Immobilization's own rhetoric concedes that there is no positive alternative to multi-national capital, confirming that Capital owns the future, and that the only option for any dissenters is to take a heroic, romantic but inevitably defeated Canute-like stance of willing back the tide of so-called historical inevitability.

Resistance to the 'new' is not a cause that the left can or should rally around. It is is not only the idea that neo-liberalism is New (the persistent association of neo-liberalism with the term 'Restoration', favoured by both Badiou and David Harvey, is an important contribution to this process) that must be challenged. What must but also be relentlessly attacked is the established consensus which holds that no alternative model of the 'New' is possible. Neo-liberals, it must be remembered, were more Leninist than the Leninists, using think-tanks as the intellectual vanguard to create the ideological climate in which Capitalist Realism could flourish. Now it is imperative for the left to think beyond - and therefore ahead of - Capitalist Realism.

Zizek's latest LRB piece is yet another example of his failure to rise to this challenge. Take, for instance, his characterization of the neo-liberal ideology of 'being smart':

'Being smart means being dynamic and nomadic, and against centralised bureaucracy; believing in dialogue and co-operation as against central authority; in flexibility as against routine; culture and knowledge as against industrial production; in spontaneous interaction and autopoiesis as against fixed hierarchy.'

Fair enough - but does Zizek want centralised bureaucracy, central authority, industrial production and fixed hierarchy? Surely not, but what is his positive political economic model?

The problem is by no means unique to Zizek, of course - and attests to the power of Capitalist Realism to make any alternative political economic model literally unthinkable.

If we are to think beyond capitalist realism - and we can because we must - a starting point would be to hijack neo-liberal rhetoric, in a gesture that would reverse how the neo-liberals recuperated the 68 critique of Fordist intransigence and the language of freedom and autonomy to legitimate their agenda. Two key terms cry out for redefinition: efficiency and wealth creation.

Naturally, the economistic agenda should be used as a trojan horse to re-introduce the extra-economic values into public, cultural and working life (the notion that activities have a social, as opposed to a merely economic, value, for instance) that neo-liberalism has eliminated or downplayed. Efficiency and wealth creation may be necessary, but they clearly aren't sufficient.

But few who have ever worked in a capitalist enterprise, or shopped in one of its emporia, could be under the illusion that capitalist institutions are efficient. Zizek has, rightly I think, drawn attention to the way in which the Deleuze-Guattari language of creative flows, deterritorialization and decentralization has been absorbed by capitalism (not that capitalism really runs on 'creative flows' of course). What he has ignored is the crucial emphasis, in Anti-Oedipus in particular, on antiproduction.

I think Dominic Fox was right a while back when he observed that the 'irruption of desire' in Anti-Oedipus, being perfectly timely in 1972, is now somewhat quaint. One of Anti-Oedipus' central problems - how will capitalism contain and absorb energies from outside? - is no longer current. Capitalism now, in fact, has the opposite problem; having all-too successfully incorporated externality, how can it function without an outside it can colonize and appropriate? Contemporary capitalism is scleroticized by antiproduction, clogged by an audit culture that is ideologically instantiated through rampant managerialism. Managerialism deliberately conflates itself with management, while claiming that managers (and entrepreneurs) who are essential to wealth creation. But managers do not create wealth; at best, they assist others (workers) to create it; at worst, they not only produce nothing, they are actually, literally counter-productive, imposing time-wasting non-work which impedes productivity by wasting time and energy. There is no opposition between efficiency and justice; on the contrary, an institution run by those who actually do the work is likely to be more effective than one run by interchangeable exploiters who often lack any specific expertise in what they are supposedly managing.

You know what, Stan, if you want me to wear 37 pieces of flair ... why don't you make the minimum 37 pieces of flair?

Much of this is summed up by Mike Judge's unjustly undercelebrated Office Space, which, with its savage satire of a corporation blighted by managerialist metastasis (six memos from six different managers saying the exact same thing; corporate coffee chains which require serving staff to wear '17 pieces of flair' to express their individuality and creativity) is as acute an account of the 90s/00s workplace as Schrader's Blue Collar was of 70s labour relations.

What is positive about the France unrest is its coalescence of a proletariat that encompasses both students and the young of the banlieus. In this respect, Paris 06 is an advance on Paris 68, when any alliance between workers and Sorbonne students who looked forward to life-long, well-paid professional careers once they dropped back in, was bound to be short-lived. Now both the students and the banlieu youth are in a very similar objective predicament. British students, needless to say, are in an even worse position than their French counterparts. The challenge is to organize the vast numbers of dispossessed youth, the precarious young, around a positive vision.

_________________________________________________________________

Much of the above has a peculiar pertinence to me at the moment, since it has just been announced that in August I will be made redundant. I should stress now that the decision to dispense with my services is based on objective economic criteria alone and is in no way connected with my role in activating the union branch at the college. (btw, I work in a Further Education college teaching 16-19 year olds, not in university, as many readers have assumed.)

__________________________________________________________________

UPDATE: Reader Hugo Wilcken responds:

"What is positive about the France unrest is its coalescence of a proletariat that encompasses both students and the young of the banlieus. In this respect, Paris 06 is an advance on Paris 68, when any alliance between workers and Sorbonne students who looked forward to life-long, well-paid professional careers once they dropped back in, was bound to be short-lived. Now both the students and the banlieu youth are in a very similar objective predicament."

This is a terrible misreading of the French situation. What is remarkable about recent unrest is the direct opposite, a total disjunction of the "proletariat" and the student population. The riots in November were notable for happening exclusively in the banlieues, and virtually not at all in Paris. The current protests are notable for the exact inverse. There has been very little coverage on what the "proletariat" out in the banlieues think of the new "contrat de premiere embauche", and even less evidence that they are strongly opposed to it. Indeed, why should they care, since about 50 percent of young people in the suburbs are unemployed and are not being offered any type of work contract at all? You're misguided if you think the banlieue youth and the students are in a similar objective predicament. Students are the civil servants of tomorrow; banlieue kids are not. The former are concerned with holding onto "acquis sociaux"; the latter are concerned about being excluded altogether from a world in which "acquis sociaux" have any meaning whatsoever.

I've heard from people who have just come back from Paris reports which support the idea that - despite my and Bat/Socialist Worker's optimism - the banlieue youth are, on the whole, neither interested nor involved in the anti-CPE protest.

However, it is a mistake to claim that the students are the 'civil servants of tomorrow'. On this point the Economist should be heeded - it is quite simply a fantasy that, if the CPE is successfully opposed, 'jobs for life' will be available. In a society in which a student with the baccalaureate can attend university, over 64% of all 15-24 year olds are on a permanent contract. A study found that, two years after graduating, only 45% of Psychology graduates had acquired permanent jobs. The overall undergraduate drop out rate is 40%. Like it or not, the students find themselves in precarity.

It's certainly true that conditions for the banlieue youth are not even precarious.

So, empirically, yes, there remains a great difference between the students and the banlieue youth. But I think it is a mistake to oppose the 'authentic' proletariat (the banlieue youth) to the students, even if both groups themselves see it that way at the moment. The proletariat is not the actually existing working (or non-) working class, but a class transformed/ brought into being via subjectivation. My contention remains that 06's generalized insecurity is proletarianizing in a way that the situation in 68 was not. The challenge, precisely, is to politicize these two different struggles in a way that will produce a proletarian subjectivity.