April 06, 2006

'Even when she tells the truth, it's a lie'

'Catherine is older in this film and the situations are different – she’s challenging the whole psychoanalytic system...' MadeinAtlantis.com

'Heck, even the way she wears her clothes is fascinating. Her costume designer has given her a series of line-straddling outfits. At one point, one hand is gloved and the other ungloved, and several of her dresses feature one clothed shoulder and one bare.

It's as if the costumer is telling us Catherine is both a heroine and a villain. Or that the movie is both very bad and very good.' - Chris Hewitt (St. Paul Pioneer Press )

What happened to David Cronenberg? Wasn’t he attached to direct this film at one point?

Sharon Stone: You know, we love him, of course. He’s so talented and so amazing, and how great was “Crash”? Ohmygod. He is the most gentle, interesting, intelligent, sophisticated person and one of my most things—it’s a little private thing but I’ll share it with you—Marty Scorsese wanted to see “Crash” so I made a surprise dinner party for him and invited David Cronenberg over to the house and screened the movie. Oh, what a fun night! You know, that was a biggie. He had really great ideas, but that would have been a very different kind of movie. I think that in the end, people just got kind of afraid that maybe it wouldn’t be so commercial, because, not to say that some of his ideas didn’t remain in the movie because they did, but what’s funny enough is that some of his ideas that they were the most afraid of remained in the movie. - Melissa Walters

Basic Instinct: a film with this many bad reviews must have something going for it...

|  |

'Basic Instinct' was a poor title for the first film, but it is clear - within seconds - that it is spectacularly inappropriate for the sequel, which glories in the fact that, far from being 'basic' or 'instinctual', human sexuality is always mediated through fantasy, fashion, technology and social role. The proposed but abandoned subtitle, 'Risk Addiction', would have been much better, but you do wonder why they didn't go the whole hog and call it Death Drive.

The film wastes no time in immersing us in preposterous excess. Its opening scene - auto-erotic in the double, Ballardian sense - sees Sharon Stone's Catherine Tramell pleasuring herself, using the ketamined-out Stan Collymore* as meat puppet sex aid, while she drives a Spyker C8 Laviolette at 120 m.p.h. through the heart of London. You conclude, even before the Spyker speeds off the road and into the Thames, leaving the bewildered Collymore to drown, that this must be some kind of dream sequence or drug delirium. When the next scene - in which Stone is interviewed by flatfooted British cops as incredulous as we in the audience are - makes it clear that, no, what you have just seen belongs to what the film is pleased to call reality, you have to ask yourself a question: what kind of a diegesis is it that expects us to treat a scene like that as realistic? The answer is a ridiculous-sublime delirial commodity porn confection of Bond, Ballard, Baudrillard and Bataille.

Basic Instinct 2 is camp, not because it takes itself too seriously, nor because it sends itself up, but because we are not sure quite how seriously it wants us to take it. Reviewer Chris Hewitt wrote that Stone 'knows Basic Instinct 2 is a comedy, and she is the only one in on the joke', but this isn't quite true. When I saw the film, in Leicester Square - an experience that was already vertiginous enough, since much of the action takes place in streets a few hundred yards away from where the cinema is located - the audience seemed quite prepared to laugh at more or less every line, but weren't sure if they were supposed to. There were many times when an isolated laugh cued others to join in, partly from relief, because they now knew, or thought they knew, how they were expected to respond.

I mean, what are you supposed to do when Tramell proclaims, with a perfectly straight face, 'Don't feel too bad ... even Oedipus didn't see his mother coming'?

Basic Instinct 2 is an uneasy experience because, although it is hyper-reflexive to the point where it is hard to think of one character, one scene, one plot twist that isn't a reference or an echo, there is nothing knowing about it. No matter how absurd the film gets, it refuses to raise its eyebrows. It flouts the cardinal rule of PoMo by keeping faith with fantasy. Fantasy, after all, is the ridiculous-sublime - that which, even when we are fully aware of its absurdity, does not relinquish its hold on us.

|  |

Basic Instinct was a mediocre reworking of the postmodern noir template established in Body Heat, notable only for the then unprecedented (in mainstream cinema) explicitness of the sex and for the icy assurance of Stone's performance as Tramell. Verhoeven cast her because she resembled Kim Novak in Vertigo. But, with Tramell, there wasn't a 'real' Judy behind the cool blond facade as there was with Novak's Madeleine; nor was there a male figure constructing the Tramell persona to entrap other males. Tramell was her own construction, a facade without an interior, cruelty withouth instrumentality.

The real enigma of the first film did concern the banal question of whether Tramell was a killer or not, but the nature of the desire driving the movie. It was posed in the infamous leg-crossing scene; was this a female fantasy of a woman subduing men with her sexuality and her confidence, or was it a male fantasy of abasement before a dominatrix? Stone gave the Tramell character a depthless invulnerability, a crystalline poise; her trademark expression a sneer-smile, expressing open contempt for those who desired her. Stone's advance on the Kathleen Turner character in Body Heat (and even over the Linda Fiorentino character in The Last Seduction, which wouldn't come out until 94, two years after Basic Instinct) was her libidinal inscrutability; she wasn't using her sexuality as a means to an end, she was just using it. She presented men with 'the horror of nothing to see', the vacancy of what they desired, knowing that they couldn't stop hallucinating a depth that she didn't even pretend was there.

|  |

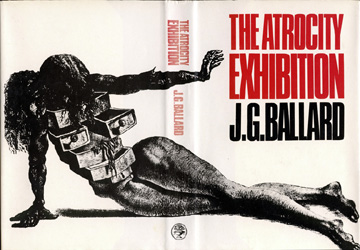

Tramell returns in the second film as a camp vamp whose persona owes more to Ballard than to film noir. Catherine is a name Ballard has often used, and Basic Instinct 2 sometimes feels that it is as much a sequel to Crash as to Verhoeven's film. Setting the film in a phantasmatic, cybergothic London means, in fact, that Basic Instinct 2 recalls aspects of Ballard's novel that Cronenberg's film, with its North American setting, didn't get to. There was little in the San Franciso of Basic Instinct - all late night bars and ocean-side drives - which would have been unfamiliar to Humphrey Bogart. But the London of Basic Instinct 2 is something we have only imagined when reading The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash. It is a London with all of the 'picture postcard' landmarks - Big Ben, Tower Bridge - erased, and presided over by Foster's phallic Swiss Re building. In addition to Foster's 'gherkin', production designer Norman Garwood - who 'wanted to champion the amazing new architecture that’s emerged in the city over the last 10 years and blend it with the classical, established London' - used the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, the Old Billingsgate Market, County Hall on the South Bank, Imperial College, the Tanaka Business School, and the 'Gothic style' Royal Holloway college as the components of his Baudelaire-meets-Baudrillard hyperreal urban phantasmogoria.

|  |

Roger Ebert, one of the few critics to admit to have enjoyed Basic Instinct 2 ('I cannot recommend the movie, but ... why the hell can't I? Just because it's godawful? What kind of reason is that for staying away from a movie?'), savoured 'the icy abstraction of the modern architecture, which made the people look like they came with the building': a very Ballardian effect. The characters, such as they are, have no more depth than the buildings they move through or the clothes they wear. Stone's wardrobe and jewellery - assembled by long-time Gus Van Sant associate Beatrix Aruna Pasztor - is certainly far more important than anything she says, the clothes far less off-the-peg than the character. Reviewers who complained about the reliance on nudity or sex weren't paying attention. The film is much more about what Stone wears that what she doesn't. Stone herself missed the point when she complained, in the run-up to the film, about the way in which the studio had cut explicit scenes. 'Everything interesting begins in the mind', goes the film's tagline, and Basic Instinct 2 would have been far more courageous if there had been no meat sex whatsoever, if the relationship between Stone and her therapist, Dr Glass (David Morrissey) had taken place entirely through roleplay and fantasy. The meat sex, as ever, is crushingly disappointing. Where the sex is interesting, it is about playing with the Other, watching the Other watching you, recounting fantasies of the Other's fantasies...

'How very Lacanian', as Charlotte Rampling says at one point.

No, really....

|  |

Both of the Basic Instinct films faced the difficulty of restoring a frission to sex in an age when its easy availability renders it banal. The solution was to re-invent the constraints that give sex its allure. Thus the hero-dupe of the first film was a cop invesigating Tramell, and in the second one it is a therapist treating her - the demands of social role magically transforming the eminently attainable Tramell into the lustrous Forbidden Object. The stiff and proper Morrissey is far better in the role of man wrestling with his professional ethics than the sleazy Michael Douglas ever was (who could doubt, even for a moment, that 'sex addict' Douglas would give in to temptation and sleep with the suspect?)

The question of what desire is driving the film is never far away. The thriller genre has always played upon the very familiar fear that we may know very little about those with whom we are most intimate, but in Basic Instinct 2 the unknowability of Others - and more, the unknowability of our own self as Other (i.e. the unconscious) - means that all the narrative elements assume a kind of superpositional hyper-instability. Nothing is resolved, or resolvable - we are in a world where everything can be reassessed or reframed at any moment: the world, that is, of ultra-precarious cybercapital, whose endlessly weaving digital labyrinths resemble the dreamwork itself. When you watch Basic Instinct 2, it is as if you are watching capital itself dream. The fantasies of the characters, the characters as fantasies, are like freefloating deliria unmoored from any individual psychological location. Tramell snares Morrissey's therapist by claiming that she fears that her fantasies are making the murders happen. But is it her thoughts which are 'omnipotent' or is she herself a commodity fetish avatar from Glass's libidinal economy? Tramell even suggests this latter possibility to him: 'Perhaps I am acting out your unconscious desires'. As the film converges with Tramell's 'grotesquely bad' fiction, Basic Instinct 2 comes to resemble Carpenter's In the Mouth of Madness, with Tramell playing a thriller-writer equivalent to the schizo-plague-propagating Horror novelist Sutter Cane. It is almost as if Tramell is a dominatrix-manipulator at an ontological as well as a diegetic level, the Author-God commingling with her characters. But by the end, when she is acting less as a character than as a narrator-commentator, it is clear that even she doesn't know what has happened.

* Collymore, for those who don't know, was a very gifted footballer who ended his career as a sportsmen at a self-destructively premature stage. Since he has ceased playing, Collymore has been exposed in a 'dogging' scandal. In the film, he plays a disgraced footballer who dies having a kind of sex in a car. Hyper-real enough for you?

Posted by mark at April 6, 2006 12:38 PM | TrackBack