March 29, 2006

The Proletarian Cogito

Tim raises a number of interesting questions over at The Wrong Side of Capitalism. The key passage is the following:

‘The materialist critique [of religion] does not assert that religion is false; indeed, it would be almost more accurate to say that the materialist critique shows that religion is true or, better, it shows in what sense religion is true, how religion arises from and so reflects material conditions. So a communist engagement with Islam would not reject Islam, but would involve figuring out how an Islamic vocabulary can articulate communist projects (and if this is not going to just be bad faith, we shouldn’t expect our own communism to come out of the encounter unchanged).’

It strikes me, though, that, even as it acknowledges the hyperstitional effectivity of religion, the Marxian argument presupposes the falsity of religion, but makes the crucial point that merely exposing this falsity can not be sufficient. Idealism stops at merely denouncing religion; materialism must live that denunciation. In the same way, ‘a ruthless demolition of commodity-theology’ must involve behavioural, not merely, cognitive changes.

Capitalism is a set of rituals. I observed in the comments boxes at the Wrong Side that it is a set of rituals that give rise to beliefs, but, on second thoughts, this is misleading. Capitalism does not require us to hold a particular set of cognitive beliefs; it only requires that we act as if certain beliefs (about money, commodities etc) are true. The rituals are the beliefs, beliefs which, at the level of subjective self-description, may well be disavowed. What is needed, then, is a new set of rituals. This leads us back, once again, to the question of what an anti-capitalist economy would look like. ‘Economics are the method, the object is to change the soul’, as someone once said.

Turning now to the question of Communism’s relation to Islam. There is a sense in which what Tim is saying – that ‘a communist engagement with Islam would not reject Islam, but would involve figuring out how an Islamic vocabulary can articulate communist projects’ - must be right. One problem, however, is that from the point of (most) believers, this kind of engagement would already amount to a rejection. I’m not sure that Liberation Theology has ever satisfactorily resolved the tensions between Marxism’s ‘social naturalism’ (the claim that all beliefs have their origins in social practice) and religion’s supernaturalism (the claims that its beliefs are underwritten by divine will).

How might an Islamic vocabulary articulate communist projects, then? Ironically, of course, given the seeming insistence on some quarters of ethnicizing Islam, one of the potentially emancipatory aspects of Islam is precisely its de-racializing and de-ethnicising emphasis. The privileging of the ‘umma’, the Islamic community, over race and nation means that Islam offers what is perhaps the only currently effective alternative 'globalism' to capitalism's multi-nationalization. In reality, of course, Islam is as riven by sectarian disputes as capital remains tied to territoriality. But the universalising impulse in Islam is perhaps something that could potentially be mobilised by communism.

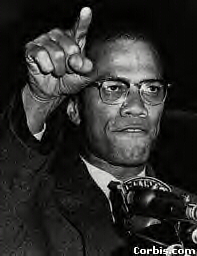

It was this aspect of Islam that Malcolm X celebrated in Islam after his epiphanic visit to Mecca. In his letter from Jedda, April 10, 1964, X called Islam 'the one religion that erases the race problem from its society' (Malcolm X Speaks, p. 59).

What is interesting here is not only that X's later advocacy of universalism differs so radically from his earlier separatism and black nationalism, but also that both positions were articulated via Islam. Malcolm's initial religious conversion was intensely racialized, and race was immediately politicized. The way that Islam was introduced to Malcolm in prison produced a kind of ontological shock, a reframing of all his previous experience. Islam was the mediator which allowed Malcolm to encounter blackness as a political category rather than a natural/social fact, enabling him to re-explain his past history of gambling and petty criminality as an effect of systemic processes. The later turn away from separatism, the shift in his anti-racist thinking from an emphasis on black nationalism towards a de-racializing universalism, followed his break from Elijah Muhhamad, if not from Islam as a whole.

Malcolm X's situation was so tied up with a specific national and historical context that it would be foolish to draw any hasty conclusions from his case. But it does seem to highlight difficulties with the race/religion matrix. One problem, it seems to me, is that the race/religion prism meant that Malcolm's separatist position and his later universalism had to be held sequentially, rather than simultaneously. Marxism, on the other hand, is not only capable of 'squaring this circle', it is based on the idea that a particular group (the proletariat) can stand in for the universal.

Bat came into the college last week to talk to the students about Marx and religion, and one of the most interesting questions, posed by a Christian student, was: what is it about religion that means that it cannot provide the basis for struggle and positive change in the way that class politics can? Bat answered as I would have answered: that religion is too tribalised and sectarian to produce an opposition to multinationalized capital.

Capital's alleged universality, the fact that - theoretically at least - it subjects everyone to an abstract equivalence, generates an antagonist which can proclaim real universality and genuine equality. Ironically, it is now, when the idea of a proletariat is abandoned - in favour of the 'multitude' or the 'people' - that the concept starts to have an unprecedented purchase on social reality. In the generalized insecurity of post-Fordist precarity, the tendency is for all labour - including that of the capitalist - to become proletarianized. This isn't to deny or in any way downplay the systematic plunder by the managerial uberclass (anyone in any doubt about that need only take a look at the graphs in Harvey's A Brief History of Neoliberalism, which show the vertiginous increase in the pay of CEOS over the last thirty years). But few people, no matter how cloistered they are in wealth, can fully exempt them from a bipolar social reality defined by unpredictable, sudden and violent change, and ruled not by the whim of individuals but by the idiot diktats of Capital.

The disaster of Cultural Studies lay in its ethnicizing of the 'working class', in its paeans to the 'dignity' of working class life, its celebrations of the microresistances supposedly demonstrated by 'subversively' watching soap operas and such like. What Cultural Studies did, in other words, was to assimilate Marxism into identity politics. That move totally undermined the basis of Marxism, which would be better described as a disidentity politics. This is not to suggest that Marxism entails the empirical destruction of identities and ethnicities. It is to say that for Marxism, collectivity is organized on the basis of an indifference to difference.

Perhaps, with Badiou and Sartre as well as Marx in mind, it is worth positing a distinction between subjectivity and identity here. Identitarianism assumes that people are condemned to identify with the positive (ethnic/ gender/ nationalistic) predicates they possess, as if their subjectivity were exhausted by those properties. Exactly the opposite is the case: the authentic dimension of subjectivity consists not in any positive identity but in that which makes identifications. Seemingly bizarrely, this is why the (Lacanian) cogito - from which, not only all biosocial facticity but any phenomenological qualia (the texture or depth of experience) have been evacuated - can serve as the basis for collective politics.

This is why the claim that the proletariat are replicants goes beyond being metaphor. The question Zizek poses in respect of the replicants in Blade Runner - 'where is the cogito, the place of my self-consciousness, when everything I actually am is an artifact - not only my body, my eyes, but even my most intimate memories and fantasies?' - can also be posed of the subjects of late capitalism. What the winds of capital have scoured away, essentially, is the ability to believe that the positive content of our identities is more than a (cultural or neurological) implant. (And isn't the real libidinal impulse behind the Cult Studs Difference Industry a desperate attempt to shore up the belief that there are those elsewhere who can still believe?) The Proletarian Cogito begins - at the point where historical materialism meets eliminative materialism? - with the affirmation of this nontheistic destitution, the renunciation of nostalgic simulations.

March 26, 2006

Cartesianism, Continuum, Catatonia: Beckett

Infinite Thought set the old men straight when she appeared on the Beckett Post War panel at the Barbican on Saturday, as part of the celebrations of Beckett's centenary.

The problem lay in the staleness of the set-up, which contextualized Beckett in terms of 'existentialism', as if not only had the last forty years of Beckett reception in philosophy - Deleuze, Derrida, Blanchot, Badiou - not happened, but also that existentialism could still be understood in the same way that it was half a century ago. Thankfully, I.T. was there to correct both these misapprehensions.

The other panelists insisted on seeing Beckett in the terms that had been established in the 1950s. Ken Gemes argued that Beckett's work was a literary expression of the death of God. Jonathan Rée, who admitted he had little to say about Beckett, proved the point by persistently talking about Sartre. From the audience, Beckett's long-time publisher John Calder insisted that Beckett was a lapsed Christian turned Schopenhauerian.

It is not that these parallels tell us nothing about Beckett. What they don't address is what is novel about his work. The death of God and of meaning had already been dealt with by Dostoyevsky in the middle of the nineteenth century. And, As I.T. pointed out, any comparison between Beckett and Sartre must confront the profound difference between Beckett's formal(ist) innovations and Sartre's classicism. (Part of what makes Sartre interesting is that he so often corresponds to Foucault's acerbic description of him as 'a man of the nineteenth century trying to think in the twentieth.')

What is new about Beckett is that his work presupposes rather than thematizes the death of God. This is effectuated in large part through his formal inventiveness, which destroys meaning rather than represents or describes such a destruction.

There is no doubt a element of Schopenhauer in Beckett's work - but it is Schopenhauer after Cantor and Freud. Gemes captured the originality of Schopenhauer's pessimism very well when he said that there had been pessimists prior to Schopenhauer who had proclaimed that life was bad, but Schopenhauer had shown why life must always be bad - because of the will's perpetual dissatisfaction with any of the objects it pursues. Freud famously read Schopenhauer for the first time while preparing Beyond the Pleasure Principle but is worth reflecting on how Freud's formulation exceeds Schopenhauer's. With Freud, it is no longer a matter of 'will' or life as it was with Schopenhauer, but of a death drive, an infinitely plasticized, artificial drive which bears no relationship to the cyclicity of nature. The fact that we are possessed, indeed animated, by this undead impulse, means that however much we may wish to give up, something keeps dragging us forward. The Unnamable's famous 'I'll go on' is not a statement of organic persistence but the voice of the inorganic todestrieb. In Beckett, pessimism might be earnestly hoped for, but it cannot be achieved. Not because of some phenomenological core of irrepressible vitality but because of the remorseless insatiability of the death drive, that excess, that 'more', which constitutively obstructs any possibility of achieving the quiescence of nirvana. Things could always get worse, but that is very far from being comforting, since we're always heading towards the worst - worstward ho! - but we shall never attain it. Beckett's figures - a much more appropriate word than 'characters' for these ventriloquist's dummies, these linguistic marionettes - seem to subsist on the transfinite plane of Cantorian continuum, which even an omniscient being could not know or exhaustively count. Is it not that God has departed, or died - it's worse than that: even if God were around, it wouldn't help.

But Beckett was well aware that human beings were inhabited by another inhuman structure, in addition to the death drive: the ceaseless jabber of language. A jabber which is a constant reminder that, much as we might want to be, we can never be alone. Language is itself an Other, and because it is always addressed to Others, or at least presupposes an abstract Other, the ineluctable impulse to write and speak is always snatching the silent serenity of solipsism away from us.

The idea that there is no metalanguage is another theme that separates Beckett from Schopenhauer (and other nineteenth century philosophers and writers, including Nietzsche, who writes about this revelation but does not yet write it). Schopenhauer's pessimism assumes a transcendent distance from which Life could be represented. But there is no such space in Beckett. The instability of any ontological frame, the recursive disintegration of any supposed meta-level of description into what is describing, is one of the major preoccupations of the Trilogy. By the end of The Unnamable, the stage is set - or rather cleared - for the hyper-pared down abstraction of his later fiction, which plays not only upon the difference between words and things but also upon the fact that words are things, material blocks of sound and image rather than transparent carriers of transcendent meaning. (Beckett's formalism, his pioneering of a post-psychological abstract fiction, makes him much closer to Robbe-Grillet than Sartre.)

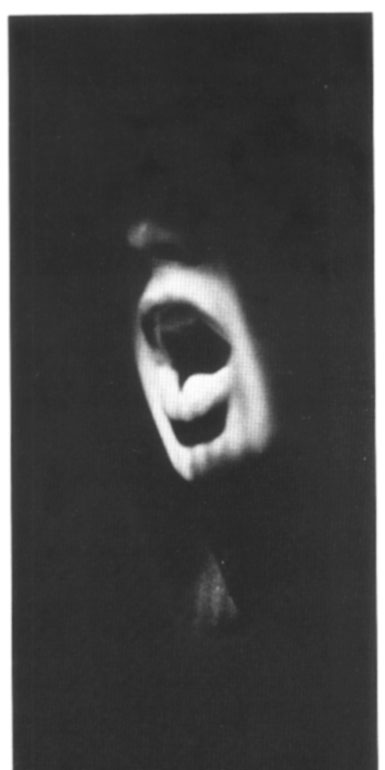

The early Watt contains one of the most uproarious sequences in literature, as the hapless lead character, instructed to feed a dog any leftovers, permutates, on page after pedantic page, all the possible ways he might satisfy this demand in the lack of a dog in the house. By the time of his late work, of course, all of Beckett's fiction is sucked inside combinatorial matrices of this type; by then, the exuberance of the naturalistic lifeworld, the whole vast panorama of Joycean Europe, has been remorselessly scoured away, and representation has collapsed into abstraction. The methodological principles governing this abstraction are guided by the Cartesian question - how much can be taken away? As I.T. remarked on Saturday, Beckett's interest in tramps was motivated by a philosophical investigation into the limits of the human. The Beckettian 'I' is the Cartesian empty space, that which is left when everything else is subtracted. Could it be that the Mouth of Beckett's 'Not I', who recounts a tale, seemingly her own, whilst denying that the story is hers, is not, in fact, in a condition of bad faith, but of Lacanian authenticity, in that she recognizes that no positive predicates, none of the things she is or has done, are ever 'that', what she 'really' is. None of this is 'me', precisely because I am not, this Not is what I am.

The combinatorial dimension of Beckett's work was perfectly illustrated by the two late plays, 'Rockaby' and 'Ohio Impromptu', which followed the panel discussion on Saturday. These stark tableaux, where bodies sit in near-catatonic near-stillness while sparse, recited text (sometimes spoken by them, sometimes by an offstage voice) is subjected to micro-varied repetition, are closer to installations than to traditional drama. It's as if the plays, their words reassembled and looped according to quasi-serialist principles, have themselves become the recorder on which Krapp played back his tapes. (As I listened to the desolate repetitions of the language on Saturday, I was reminded of Burroughs, another formalist innovator very much influenced by cassette recorders; Beckett famously abominated the cut-up technique, but there's something in the depersonalized mechanism of his later texts which recalls the machinic melancholia you often hear in the cut-up novels.) Or it's as if an abstract painting has come to (bare) life - or, better yet, as if life has been ascetically reduced to the stillness of painting.

But not, perhaps, reduced enough in these productions. I had never seen any of the later plays staged before, and their intense physicality - the rigor not quite mortified poses of the bodies, the harshness of the lighting on the faces - cannot even remotely be rendered by reading alone. Here, 'live' theatre regains its power precisely by subtracting the 'living' and the 'theatrical' - the shrill mugging of theatre acting is replaced by the stasis of bodies assuming the unvitality of the catatonic. Yet, as I.T. complained, the actors and the director could not seem to prevent themselves from interpreting Beckett's notoriously precise instructions. (Hence Beckett's famous exasperation with actors.) There was altogether too much expression in the way the words were recited; and in 'Rockaby', in an addition to the script which fatally marred the Barbican production, the old woman finally rests her head on one side, as if lapsing into the repose of death, a movement which disastrously shifts away from the play's purgatorial interminability (in which there is always, implicitly, the possibility of something more, worse luck) towards a much less unsettling finality. The productions inevitably prompted the question: can any actor do justice to Beckett's austerity? Is the temptation to expression and interpretation always too much for any actor to resist? What is required is the catatone of a meat puppet, and I wondered if Beckett's scripts hadn't posed a problem that only AI imagineers or CGI animators can solve. Perhaps only an artificial life form can adequately give body and voice to Beckett's human unlife.

Badiou argues that Beckett reduces the human to three essential (or 'primitive') functions: 'movement and rest (to go and to stall, or to collapse, fall, lie down), being (what there is, the places the appearances, as well as the vacillation of any identity whatsoever); language (the imperative of saying, the impossibility of silence).' What makes Beckett our contemporary is the uncanny similarity that these reductions share with those performed by cyberspatial capital. What do we look like from cyberspace? What do we look like to cyberspace? Surely we resemble a Beckettian assemblage of abstracted functions more than we do a wholistic organism connected to a great chain of being. As games players, we are merely a set of directional impulses (up, down, left, right); as mobile phone users, we take instructions from recorded, far distant voices; as users of SMS or IM, we exchange a minimalized language often communicating little beyond the fact of communication itself (txts for nothing?)

URGENT UPDATE: Bat corrects me on Cantor. Every time I try and write something about Cantor or Godel, I show why I failed maths O-level. I understand the issues, just about, but I can't explicate them anything like adequately. But Bat's proper explanation of Cantor below makes the parallel with Beckett even more compelling I think. Over to Bat:

"seem to subsist on the transfinite plane of Cantorian continuum, which even an omniscient being could not know or exhaustively count"

This attempt to weld D&G "plane"-speaking onto Badiou-style mathematical ontology doesn't work, for two reasons.

1) The fundamental point about Cantor's version of the continuum is that it isn't a "plane", or even a "continuum" for that matter, any more. Cantor abstracts away ALL geometric notions and conceives the continuum as pure cardinality, or pure "quantity" as Badiou puts it.

Hence the startling result that the geometric continuum (ie a line stretching to infinity in both directions) is "equivalent" (ie has the same cardinality as) the power set of the naturals (ie the set of sets of whole numbers), despite the utter lack of any "intuitive" (ie imaginary) resemblance between these two multiplicities.

2) The epistomological uncanniness of the continuum lies in the fact that although we can demonstrate (given the axiom of choice) that the continuum HAS a cardinality, we cannot demonstrate WHAT that cardinality is (we have to decide it).

The "working mathematician" typically domesticates this uncanniness precisely by invoking the comforting notion of a god that secretly "knows" what the cardinality of the continuum is. This is a standard trop (sometimes "secularised" in talk of a meta-language) of the platonist-realist ideology that Badiou ruthlessly criticises.

But Badiou's point is that thinking of all this in terms of what an omniscient being could or could not "know" is deeply misleading. The point isn't to counter "only a god can save us" with "even a god can't save us" (which merely extends rather than opposes theological pathos), but to state something far more disturbing - that a god would be in exactly the SAME position that we are, and that consequently all this fuss about unfillable holes in knowledge amounts to nothing more than Feurbachian alienation, projecting onto God the powers that we are unwilling to acknowledge in ourselves.

March 20, 2006

Telecommunism

Really excellent post by Angela Mitropoulos at s0metim3s, which allows me to make some clarifications. (I can only imagine that the Hectoring Heiress has straw-manned me, that's one of her standard techniques - but as I say I'll be avoiding that particular whirlpool of reactivity from now on. Better things to do, joke's over...)

Angela is right that appeals to what Marx 'really' said will be both cultish and futile, in part because Marx's writings are often contradictory. (In his schizoanalysis of Marx Libidinal Economy, Lyotard even suggests that 'the desire named Marx' is constituted by two distinct drives pulling in different directions: the drive to have done with capital and the critique of capital on the one hand, and the drive to endlessly prosecute the case against capital on the other.)

In any case, the authentic Marx is a chimera. The salient issue, though, is what is distinctive and original about what Marx said.

Two things distinguish Marx from hand-wringing socialism. First, the systemic nature of the critique. It is capital, not capitalists, that is the proper object of attack. The ethical impulse to replace capitalism will not be effective while it takes the form of a moralising attack on individuals. (Just to be clear: my attack on the Heiress was not based upon her currency trading, but on her currency trading while maintaining her obsessively personalizing mode of invective. If she were arguing that we are all puppets of capital, fair enough - but she has explicitly repudiated that position in the past. The charge is inconsistency, not immorality.) More than that, to focus on the failings of individuals is to actively assist capitalist ideology by implying that capital is reformable, that it would be an equitable system if only the people 'running it' were nicer. 'Nice capitalism', capital with a 'good heart', is in fact the currently dominant ideological mode - what Padraig has called 'Bobonoism', i.e. the Geldof/ Bono model of protesting as you shop, caring-sharing credit cards, the fake universalism of a populism with which 'no-one can possibly disagree'. In place of this liberal ethical commonsense, we need to insist on taking Marx's Gothic language very seriously. Capital is the hypernatural vampire, the zombie-maker, self-engendering monstrosity, a planetary artificial intelligence.

Second, the modernist Marx. You can see this in many places in Marx. Witness for instance the passage in The Communist Manifesto, where he and Engels delight in the way in which capital has liberated the peasantry from 'rural idiocy'. The Lyotard of Libidinal Economy and Duchamp's Trans/Formers provocatively combines modernist aesthetics with Marxism to propose that the inorganic body of the proletariat - an artificialized body, utterly cut off from the supposed organicism of the peasantry, bred as a machine part in the labs of capital to withstand the inhuman conditions of the factory and therefore capable of a whole new affective range - is the greatest modernist product ever. Lyotard scandalised the bleating socialists of his day by writing of a proletarian jouissance: ' the English unemployed did not become workers to survive, they - hang on tight and spit on me - enjoyed the hysterical, masochistic, whatever exhaustion it was of hanging on in the mines, in the factories, in hell, they enjoyed it, enjoyed the mad destruction of their organic body which was indeed imposed upon them, they enjoyed the decomposition of their personal identity, the identity that the peasant tradition had constructed for them, enjoyed the dissolution of their families and villages, and enjoyed the monstrous anonymity of the suburbs and the pubs in the morning and the evening.' Programme for a post-Soviet constructivism: to extract this masochistic jouissance of artificiality, the inorganic and the anonymous from capitalism and put it to work for communism.

There is indeed, no opposition to be drawn between capitalist progressivism and reactionary nostalgia. Let's be clear: there is no capitalist progressivism. But that is not to say that there aren't 'progressive' tendencies within capitalism, tendencies that are, by the very nature of capitalism, necessarily and inevitably blocked and inhibited. Which is to say: capitalism is defined by - is in many ways nothing more than - the tension between progressive and reactionary tendencies; the progressive elements can only be liberated from the reactionary ones when capitalism is destroyed.

Here Deleuze-Guattari's account of capitalism remains indispensable. Precisely what Deleuze-Guattari emphasise is that the oscillation between deterritorializing and reterritorializing tendencies is constititutive of capitalism as such. Capitalism can never pursue deterritorialization to the absolute. What deterritorialization there is within capitalism is always balanced by a compensatory lockdown onto nation, culture, and race. Hence the 'Steampunk' quality of capitalism, where the most ancient traditions can co-exist with the ultramodern. I love the idea of nationalized, ethnicized capital that Angela draws out (while people become more de-ethnicized, money remains hyper-ethnic?)

If, as is certainly the case, capitalism cannot do without nationality, that is precisely why accelerating and intensifying the deterritorializing, de-ethnicizing and anti-national impulses within (but inhibited by) capitalism constitutes an anti-capitalist strategy. The communist-pyschotic position is to take capital at its word: to demand the universality and globalism it proclaims but can never deliver. (Again, Angela is right - inter-nationalism is not sufficient.)

The proletariat are factory-farmed replicants who believe they are something called the working class. The task for telecommunism is to strip out the false memory chips binding them to the quasi-organic earth, in order to produce a New Earth for a 'people that do not yet exist'.

March 17, 2006

Neither Washington nor Tehran...

This has gone on too long.

Make no bones about it, Zizek's latest piece is full of sloppy errors and hasty rhetorical moves. And the central problem with it is, indeed, that it makes too many concessions to liberalism. But its liberalism consists in the genuflection to the concept of 'respect' ('respect for persons' being the founding tenet of liberalism). The accusations made by Lenin and the always ludicrous but now totally discredited Le Currency Trader amount to the opposite: that Zizek is not liberal enough, that he is insufficiently 'culturally sensitive', not deferential enough to the pieties of cultural difference.

Le Trader confuses intensity of hysterical sanctimony with radicality of position. I'm not going to link to her site again; too many intelligent people have already wasted too much time by being drawn into that vortex of unreasoning resentment and rhetorician's spite. The (surely no surprise to anyone) revelations on Long Sunday that Le Trader is a full-on capitalist (but it's OK, she has a good heart, and no-one who reads her can doubt for a moment that the milk of human kindness flows from her every pore) are less humiliating than the way she outs herself as a total naif, innocently unaware of even the first principles of Marxism (what, capital is abstract? You mean that it's not about bad people and stuff?) It now becomes clear why Le Opera Goeur was so keen to reject the attack on populism; she wants to retain the category of the bad capitalist so she can keep open the possibility that are good capitalists (like... guess who). Perhaps they didn't get onto Marxism at her finishing school. What is clear is that Le Trader's moralizing liberal socialism (placard-waving whining at the Man) is not only ignorant of Marxism, it is what Marx came to abolish. Le Trader is so much like a fantasy figure for the anti-Left, so exactly fitting it caricature of a Leftist is like, that you do sometimes question whether she's real and not some neo-liberal concoction.

Le Trader's pathologies would be merely uninteresting, nasty and unpleasant if some of the stances she takes up weren't shared by less reactive, more intelligent minds on the left. The important question is: how has it come to this, where large areas of the Left have effectively ditched Marxism in favour of guilt-mongering Cult Studs meta-orientalism? Imagine if the SWP put all the energy it is currently devoting to shore up its Islamophiliac stance - ALL that rhetorical evasion and Jesuitical sophistry - into developing anti-capitalist strategies and tactics. Sometimes, in the midst of the ceaseless blizzard of quasi-McCarthyite Islamophobic denunciation, you begin to wonder if the conspiracy theories about 9/11 being a deliberate attempt to stop the anti-capitalist movement were actually founded. Just in case there is any doubt: I in no way underestimate the importance of Islamophobia; I in no way retreat from anything I said about the facile nature of the pseudo-concept of 'Islamofascism'. It is just that I refuse to accept that Islamophilia is the opposite of Islamophobia; I refuse to equivocate between defending Muslims from racist attack and defending Islam; and I refuse to renounce the centrality of atheism to Marxism. The simple fact is that Marxist explanations are in competition with religious explanations. It's true that the same rages and frustrations which might lead someone to become a Marxist could also influence someone to turn to 'political' Islam. But Marx's point about opiation was that religion's next-wordly orientation will always disguise and mystify the social and economic causes of suffering, and thereby perpetuate them. Islamic Marxism would be a way forward, but this would entail a politicization of Islam not the Islamicization of politics practised by all the variants of really existing political Islam of which I am aware. (I sincerely hope that there are some other modes of political Islam out there at the moment... someone tell me where they are.)

The irony of the SWP's position is that it exactly falls into the logic previously repudiated by Trotskyists, that of an either-or disjunction between equally unpalatable alternatives. Where once Trotskyists refused to accept the false 'choice' between capitalism and Stalinism, proclaiming 'neither Washington nor Moscow but international socialism', now the SWP seems to accept that it is a straight choice between EITHER capitalism OR political Islam, no buts. It has, in other words, obediently complied with the thinking of its Master (Signifier), the US, colluding in the racial delirium of 'one lone madman' that has replaced the MAD logic of cold war paranoia.

Zizek's attempts to step outside the USA/political Islam pseudo-opposition by introducing Europe as a third term are no doubt hamfisted. But his reflation of Eurocentrism has to be seen conjuncturally, in the context of the racial delirium of US supremacist-fascists like Mark Steyn, with their tiresome denunciations of Old Europe and 'Eurabia'. To trumpet Europe and atheism in the New York Times constitutes a provocation: better atheist Eurabia than fundamentalist USArabia. USArabia is the neo-con project for a new fundamentalist century, the reality of the US-political Islam complicity that lies behind the 'official' stand-off between the US and Islamism. As Hamid Taqvaee of the Worker-Communist Party of Iraq has argued, US neo-conservatism has fed a resurgent religious climate from which political Islam has profited. We all know of the longstanding links between the US and bin Laden; and we need to remember that the US has looked mightily unperturbed while the previously secular Iraq has acquired its first Islamic constitution.

To believe that US 'Islamophobia' is really and actually an attack on the religion of Islam is to make both an empirical and a structural error. The empirical fact is that the US is shoring up fundamentalist regimes everywhere. Structurally, as is evident, the role of the 'Islamic Terror' is to fill the gap left by the disintegration of Stalinism. That is why Saddam's quasi-Stalinist Baathist regime was the perfect transitional object for the US in the immediate years after the Cold War ended. Saddam was no more a Muslim than Stalin was a Christian. But he was 'Muslim' in the way required by the racializing fantasy; Middle Eastern, dark complexion, not Israeli.... This racist delirium, which equates sworn enemies like Saddam and bin Laden (the only thing they have in common is that they were both funded by the US), will therefore find victims amongst Sikhs, Hindus , atheists, anyone, in fact, whose skin tone or look belongs to a certain ill-defined category, as well as amongst Muslims. So any defence of Islam spectacularly misses the point of what Islamophobia actually involves.

What is needed now more than ever is a certain coldness, a certain refusal of sentimentalism. (And Le Trader might like to come on all hard bitten cynical, but at bottom she's a sentimentalist; what is her Lawrence of Arabia-style fetishising of Third World struggles if it is not sentimental?) We need to do just as Marx recommended, and accelerate, not resist, capital's destruction of traditions, ethnicities and territorialities. It might be tempting to find bolt holes of reactionary tradition in which to take flight from the scouring winds of capital, but it is a temptation to be vehemently resisted. The non-organic product of capital's 'Frankensteinian surgery of the cities' (Lyotard), the proletariat emerges from the destruction of all ethnicities, the desolation of all tradition, the destitution of any home.

Marxist atheism is not to be mistaken for the Last Man sniping at religion I have previously attacked, and which I continue to deplore. Crucially, Marxist atheism is only achieved once the theological critique of capitalism is completed. This is what separates Marxist atheism from the gliberal platitudes of the likes of Nick Cohen, who proclaim secularism while remaining attached to the theology of capital (liberal commonsense). Theism is defined not by any positive beliefs, but by the role of the fetish or totem as transcendental guarantee of any reality system. The critique of religion is the 'premise of all critique' because critique is about the exposure of such fetish-guarantees. It is necessary to recognize that capitalism is very far from being anti-religious. On the contrary, it is, as Karatani puts it in Transcritique, a 'relgio-genic-process'. 'Whether or not we believe in religion in the narrow sense, real capitalism puts us in a structure similar to that of the religious world. What drives us in capitalism is neither the ideal nor the real (i.e. needs and desires), but the metaphysics and theology originated in exchange and commodity form.' This theology continues to evade critique because it is a disavowed theology, obscured by ideology. We don't really believe that capital is an autonomous force, we know (so we think) that the only reality is that of free individuals. The full confidence in the 'reality' of our free individuality is precisely the ideological feint which allows us to act as if commodities are autonomous. The critique of capitalism therefore entails a ruthless demolition of commodity-theology and its support in the social fetish of the 'free individual'.

Neither Washington nor Tehran but international communism...

March 15, 2006

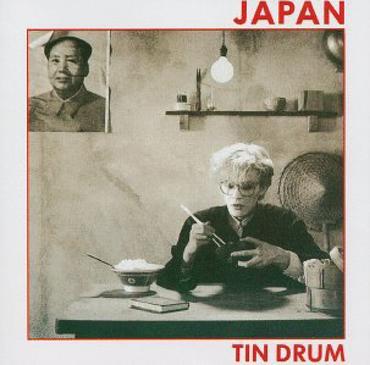

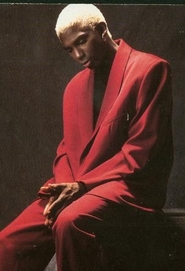

The Barthes of Parties

To celebrate my discovery of this, Japan's Top of the Pops' performance of 'Ghosts' in 1982, on youtube.com, I re-present below my observations on Tin Drum, from the old blogspot site. (I would just link, but, since the site has been hacked by corporate interests, that's not straightforward....) This was one of the two or three TOTP performances which had most impact on me, one which I replayed in my memory (imperfectly, inevitably - I remembered Sylvian wearing a checked shirt) many times, but which, until a few days ago, I hadn't seen since it was first broadcast. Watching it again now, the clip has an almost heartbreaking power, bringing a visceral recall of the time, before MTV and multi-channel and endless repeats and DVDs, when pop on TV was a rare commodity, when TOTP could produce moments of life-altering wonder. (I can't remember if I saw the TOTP appearance before or after I bought the 'Ghosts' picture disc, for 99p. I do remember playing the single over and over after I bought it, and, it remains to this day almost certainly the pop track I have played most. Everything on Tin Drum possesses a wealth of detail that never quite seems to exhaust the capacity to surprise.) But it is also heartbreaking because of Sylvian's beauty; a beauty that, evidently, was so fastidiously cultivated, so artificialized - check the way his eyeshadow gives his eyelids an almost opiated heaviness - but, at the same time, so painfully fragile; his face a Noh-mask, anaemic ultra-white, his body posture, ragdoll drained. Here he is, one of the last Glam princes, and perhaps the most magnificent - his face and body rare and delicate works of art, not extrinsic to, or lesser than, the music, but forming an integral component of the overall Concept.

Any way, the original piece, below:

Will pop ever get this exotic, this esoteric, this arty, again?

Japan's Tin Drum: the moment when art pop went abstract. Tin Drum was, at one and the same time, the most popular and the most avant-garde Sylvian ever did. His subsequent retreat into Serious Artist and Wire Cover Star - is all very admirable, his solo albums are unquestionably Good Records, but there is nothing there to compete with this.

Tin Drum is possibly the most superficial album ever made. And if the Wire consensus is that Sylvian has matured, grown since then, it is because of a kneejerk rejection of the superficial. Sylvian, now, is Deep, and therefore, better. But as Deleuze says in The Logic of Sense, why, if superficiality is defined as lack of depth, is depth not defined as lack of surface?

A superfluity of surface on Tin Drum.

Take the cover, for instance: Sylvian, his heavily sprayed, peroxided fringe falling artfully over his 1981 Trevor Horn specs, sits in a simulation of a simple Chinese dwelling, chopsticks in hand, as a Mao poster peels picturesquely from the wall behind him. Everything is posed, every Sign selected with a fetishistic fastidiousness.

And, naturally, all (social, political, cultural) meaning is drained from these references. When Sylvian sings 'Red Army needs you' on 'Cantonese Boy', it is in the same spirit of semiotic orientalism: the Chinese and Japanese Empires of signs are reduced to images, exploited and coveted for their frission.

Gentlemen take polaroids, indeed. And, by the time of Tin Drum, Japan have perfected their transition from Dolls-trash-hounds to gentlemen connoisieurs. Tin Drum's superficiality is the superficiality of the (glossy) photograph, the group's detachment that of the photographer. Images are decontextualised, then re-assembled to form an 'Oriental' panorama that is strangely abstract: a Far East as Roussel might have (re)imagined it. The words are little labyrinths, enigmas with no possible solution, false-fronted follies decorated with Chinese and Japanese motifs.

And what of Sylvian's vocals? By now, all of the ersatz Amerikan swagger of Adolescent Sex is barely remembered, and Sylvian has long since perfected his Hong Kong-plastic mass-produced copy of Bryan Ferry.

Recall Ian Penman's analysis of the Ferry voice - how its peculiar quality came from an only partly successful attempt to get his geordie accent to forge a classic, timeless Englishness. Sylvian's voice is the faking of a fake. The almost whinnying quality of Ferry's angst is retained, but transposed into a pure styling devoid of emotional content. It is culture(d), not natural at all; prissy, ultra-affected but lacking in affect. Even on 'Ghosts', it does not ask to be taken at face value. It is not a voice that reveals, or even pretends to reveal, it is a voice to hide behind, a mask, just like the make-up, the conspicuously-worn sino-signs.

Unlike adolescents, Tin Drum's gentlemen never talk about sex (nor about any of rock's traditional preoccupations). In place of rock's panting carnality, Tin Drum exudes a diffuse, almost asexual, sensuality. No love/ lust pains/ paeans then - only enigmatic references to doubt, regret, passing youth, which are (like everything else) sublimated into (all-but) meaningless signs. If rock's emotional register has been superceded, so has its habitual sonic expression - all of rock's jerks and spurts, its mad dashes and explosions, its tensions and releases, have been expertly smoothed away. As has rock's abrasion : Tin Drum has a robust softness , a springy pliancy .

Sinuously undulating, lazily uncoiling like a serpent in the sun, Karn's bass is the lead instrument, the album's supple spine. In bearing the weight of holding the tracks together, Karn absolves the other sound-sources from any functional responsibility. Jansen's drums - now loping tom-toms, now sin-snare cracks - don't so much keep time as add rhythmic decoration. And most of the other sounds occupy some indeterminate position between percussion and synthetic sound effect. There's a fullness that is never fussiness: sounds are splashed here and there with a pseudo-spontaneity that belies a painterly dexterity. Attention to detail is all. Tin Drum is a masterly exercise in pop as pure texture. Don't look for depths, run your fingers along the surface. The bassless and beatless 'Ghosts', one of the greatest singles ever made, is an exercise in pure texture, mood music that has no ancestry in blues, jazz or any 'authentic' form at all.

Tin Drum's sinofunk is definitely (a) dance music. For all its density and detail, Tin Drum has the rhythmic spaciousness of Can, compressed into the format of a three-or-four minute pop song. Except on 'Sons of Pioneers', where Japan allow themselves to venture beyond pop's (time) limitations to explore a desolately beautiful prairieland of sound, electronics twinkling like distant stars in a moonless sky.

And after this? Well, for Sylvian, there is the return to authenticity, which - as always - is connoted by two things: the turn away from rhythm and the embracing of 'real' instruments. The wiping away of the cosmetics, the quest for Meaning, the discovery of a Real Self....

I can't be the only one who hungers for a pop - or a dance - music - that could re-discover the wondrous superficiality of Tin Drum.

Further notes added later in response to Simon's comments:

The 'Emotional' Sylvian is certainly the exception rather than the rule on the Japan records. It's not only the fixation on geography ('Communist China', 'Taking Islands in Africa') that makes Sylvian seem like a tourist, or should that be gentlemen-explorer? And a tourist, also, in his own 'inner life'? It's almost as if Sylvian - or at least the post-Dolls Sylvian - starts off where Ferry ends up, stranded in an 'other world of pure atmosphere, autumn swirl of shrivelled or dying signs (that once were lustrous: 'dance' - 'drug' - 'love'), making solemn play of an immensely empty escape in the facades of an eternal tone - windswept, misty, limpidly sensual, banal.' (Penman) Like Ferry, Sylvian remains Subject as well as Object: not only the frozen, feminized Image, but also he who assembles images, not in any pathological, Peeping Tom -sense, but in a coolly detached way. 'Gentlemen take polaroids/ they fall in love...' Taking pictures of themselves as they do so?

Also on YouTube:

Sylvian and Sakamoto 'Bamboo Music'

Japan Cantonese Boy and, sumptuously, The Art of Parties from Whistle Test. 'The Art of Parties' should have spawned a whole genre of hyper-abstract white funk.. check out the instrumental break at the end, like a speeded-up sino-ized Zapp... (Note here the end credits, which list the other bands that featured on the show... one cannot fail to notice mention of Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul, whose earnest mediocrity was the very antipodes of Japan's imperious, excessive anti-nature - but who, it seemed to me at the time, were on every single edition of Whistle Test, grim avatars of the reality principle, soon to lay waste to everything...)

March 09, 2006

Attack of the Capitalist Realist Straw Women

|  |

'Every day seems like a natural fact/ but what we think/ changes how we act...' - Gang of 4, 'Why Theory?'

'Neoliberalism ... has pervasive effects on ways of thought to the point where it has become incorporated into the common-sense way many of us interpret, live in, and understand the world.' - David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism

Last Friday, as a long, bitter and ultimately successful battle to wrest control of the union branch from managerialists was nearing its end, I was around the college to sound out staff views. I asked a couple of members of staff what they thought of the union, and suddenly found myself in a situation akin to that moment in a Horror or Science Fiction film when the protagonist discovers that the 'people' he is talking to are Not Like Us.

I had naively expected that more or less all lecturers would support the union in its struggles against the continuing implementation of the government's authoritarian-bureaucratic 'compliance' agenda and the spread of neo-liberal 'reforms', if not out of principle then for reasons of personal expediency. But I found myself talking to (pod) people from my worst imaginings. Neo-liberal Stepford Wives. The effect was heightened by sleep deprivation and adrenal depletion: everything felt edgy but at the same time distant, disconnected, as if shot through a fish-eye lens. Words came at me very quickly, while my responses were desperately slow, in part because I was scarcely able to credit what was I was hearing.

Here were people who really, genuinely seemed to fully believe that 'it isn't for the union to criticise management. Management are there to manage. That is why there are managers and workers.' (Interesting how, as Harvey suggests in his book on neoliberalism, the neoliberal ethic of 'freedom' is so often accompanied by an utterly credulous faith in authority.) The union shouldn't raise the issue of the principal's salary because 'he is on a different contract to us. The market rewards different skills differently.' Click, whirr. The union shouldn't complain about increasingly invasive appraisal systems because vacant Stepford blink 'that's the real world, and we can't change that here.' 'Where my husband works' (uh-oh) mirthless Nanette Newman smile 'all staff are appraised and if they fall into the bottom 20%, they will be sacked.'

Was this some kind of loathsome awake dream, in which Capitalist Realist Straw Women from my unconscious had assumed a corporeal form?

At this point, a member of middle management barreled into view, as rotundly pleased-as-punch with himself as a minor character from Dickens. 'Yes,' he boomed, (sounding for all the world like one of those puffed-up local dignitaries forever telling young Pip that he 'should be grateful to them what 'ave brought 'im up by 'and'), 'You should count yourself lucky that you've got this management! I think we should bring in performance-related-pay. If a student leaves your course, you should lose money from your wages, instantly!'

What was interesting, theoretically-speaking, about what all three of them had to say was its complete lack of any ethical or even economic argument for the rapacious state of affairs they were cheerfully advocating. At most there was an implication that neo-liberalization would lead to greater efficiency. But the main appeal of their arguments was not to 'improvement' of any kind, but to 'reality'.

An ideological position can never be really successful until it is naturalized, and it cannot be naturalized while it is still thought of as a value rather than a fact. In the case of the lecturers I was talking to, it seems that Capitalist Realism has been so successful in installing Business Ontology that there is no longer any question of evaluating it at all. Business assumptions are now transcendental presuppositions, defining the horizons of the thinkable. It is simply obvious that everything in society, including education, should be run as a business. It is simply obvious that no other criteria can come into play. Hence the reason that my flailing attempts to raise issues of 'justice' were not so much rebuffed as greeted with blank incomprehension.

But it is not only that Business Ontology cannot be evaluated within the framework of Capitalist Realism. Evaluation of any kind is foreclosed by Capitalist Realism, which is all 'is' and no 'ought'. Insofar as there is an 'ought', it is subordinated to the Capitalist Reality principle: we must fall in line with what must be the case. The 'must' of ethical duty is quickly elided with the 'must' of causal necessity. There is a kind of reversal of Kant, the slogan now not Kant's 'you can, because you must' but Capitalist Realism's 'you must, because there is no alternative'. This accounted for the lecturers' otherwise baffling obsesssion with 'research' (i.e. the union shouldn't complain about management wages until it had 'researched the contracts', as if establishing the legal status of such contracts would somehow settle the question of their fairness.) We must diligently consign ourselves to 'research' because the nature of reality has already been decided, by an Other, and all we can do is find out about it. (Harvey again: 'In so far as neoliberalism "values market exchange 'as an ethic in itself, capable of acting as a guide to all human action, and substituting for all previously held ethical beliefs", it emphasizes the significance of contractual relations in the marketplace.' Note that I think we need to put 'market exchange' in inverted commas here; markets in Really Exisiting Capitalism are an ideological construct rather than an actuality.)

A number of hyperstitional questions remain, however. If we in education are not 'in the Real World', and the Real World is characterized as a place of relentless Hobbesian struggle, exactly why should we accept the incursion into our alleged idyll of the Business serpent? Since it has been possible to sustain our Unreal World, thus far, why should we not fight to preserve this unreality?

But all this talk of the Reality of business needs to be taken with more than a pinch of salt. I mean, it's not as if dealing with teenagers every day is living out some escapist fantasy while performing PowerPoint presentations to irritable CEOs and spooling out vacuous semiotic pollution puts you in unshielded contact with the seething burn-core of the cosmos.

Anyone doubting this need only watch The Apprentice, which should be compulsory viewing for all Marxists. The programme serves the indispensable function of massively desublimating and demystifying Business, amply demonstrating that the supposed 'Reality' of Business is inseparable from the most facile fantasy structures. Pathetic self-delusion, baboonery dressed up in Harvard Biz School lingo, massive ego over-investment in projects so abjectly inane that they are not even pointless: suddenly it all becomes clear why Capitalism is so mired in banality and incompetence.

March 07, 2006

Their own musical hero

I used Natalie Hanman's piece on the Arctic Monkeys in a Critical Thinking class on Monday. It's a gift for teaching Critical Thinking, because it is packed full of obvious, classic fallacies which students can easily spot (ad hominem attack! Straw man! Inconsistency! Irrelevant appeal to popularity! Irrelevant use of statistics...) The interesting thing is that, without any prompting at all from me, most of the students were soon asking: 'Is this real?' Even those students who like the AMs - actually, especially those - could not believe that someone in their age group would produce an article like that. (For the record, when defending the AMs against the charge that they sounded retro, the students who liked them tended to appeal to the lyrical content - 'they sing about ringtones' - rather than any of the group's sonic qualities.)

Also - remember when I speculated that 'I bet the Arctic Monkeys just love hip hop?' Well, in its report on the NME Awards a couple of weeks ago (February 24 edition), the Times wrote that 'the Sheffield quartet struggled through wellwishers to meet their own musical hero, Kanye West.' Exactly when did this wearisome convention whereby Indie bands feel that they must declare love for black or dance music which clearly has absolutely no influence whatsoever on their own hyper-caucasian Trad rock sound start? I mean, at least Morrissey's 'reggae is vile' was honest. Was it the Stone Roses - or maybe their champions - who initiated this trend, with the pretence that the SRs' repermutation of the white rock ubercanon had some positive relation to rave, rather than offering a reactionary alternative to it? 'Fools Gold' is the only one of their tracks that doesn't sound like 80s Merseybeat, and it is one of the most overrated records ever. It's always reminded me more of a pub band doing an Ege Bamyasi cover than anything resembling rave. Owen says that 'I Wanna be Adored' sounds like the Cult. I'd say the Cult if they had started out in 1967. As a stroppy Byrds tribute band. Playing in a Merseybeat style.

March 04, 2006

Nomadalgia: The Junior Boys' modernist MOR

I've lived with the new Junior Boys' album So This is Goodbye for nearly two weeks now... Or rather, it has lived with me and taken me over - its melodies taking up residence in the back of my mind, its moods interleaving with my own - a benign narcotic that grows more sweetly addictive with each listen. There's no question it's a masterpiece, but I suppose you knew I'd say that.

So This is Goodbye is to be released on Domino, also home of the Arctic Monkeys, and it's an absurd irony that many casual listeners would cast the Junior Boys, not the AMs, as retro. That's because rock has been eternalized, removed from any responsibility to renew itself, whereas electronic pop is cursed to be forever associated with a brief period in the 70s and 80s. But the synthpop revivalist tag has always been misleading and reductive in the case of the Junior Boys. Some of the Junior Boys' textures may be borrowed from synthpop but, formally, their songs would be impossible without twenty years of the rave discontinuum. And where synthpop was self-consciously European, the Junior Boys have pioneered an electronic Pop that speaks in a Canadian accent. So This is Goodbye is a deeply Canadian record: crisp and white, like the Canadian winter.

Synthpop remained attached, for the most part, to the three-minute format; 'extended' remixes were a concession to the imperatives of Dance. But space comes as standard with the Junior Boys. Only one of So This is Goodbye's 10 tracks is under four minutes. Space is integral , not only to their sound, but to their songs. Space is a compositional component, a presupposition of the songs, not something retrospectively inserted at a producer's whim. The pauses, the imagist-allusiveness of the lyrics, the breathy phrasing would not work, or make much sense, outside a plateau-architecture imported from Dance; crushed into three minutes Junior Boys' songs would lose more than length.

|  |

The point can be reinforced by comparing So This is Goodbye to another recent electronic pop LP, Goldfrapp's Supernature. Supernature's conceit is beautifully simple: imagine an alternative history of pop in which glam rock was played on synthesizers. The Alvin Stardust with moogs thing is often winning, but the form of the Goldfrapp Song remains pre-House, whereas House provides the template for much of So This is Goodbye's version of Pop. House references are everywhere: the title track is gorgeously, oneirically poised on a honeyed Mr Fingers' plateau, and it is not only the arpeggiated synth which drives many of the tracks that is reminiscent of Jamie Principle. Yet the LP does not sound either like House or like most previous attempts to synthesize Pop with House. So This is Goodbye is like House if it had started in the wilds of Canada rather the clubs of Chicago. Too many House-Pop hybrids fill up House's Space with business, hectic activity. On Vocalcity and, to some extent The Present Lover, Luomo did the opposite: dilating the Song into an unfolding driftwork. But the Luomo LPs were more Pop House than Pop per se. So This is Goodbye is, however, very definitely a Pop record; if anything, it's even more seductively catchy than Last Exit.

The obvious difference between So This is Goodbye and its predecessor is the absence of the tricksy stop-start stutter beats on the new record. (That aspect of the Junior Boys will be explored and extrapolated by former JB Jonny Dark, whose record is soon to be released by the JBs' old label, kin.) If Junior Boys' inventiveness is no longer concentrated on beats, that is a reflection as much of a decline of the surrounding Pop context as it a sign of the JB's newfound taste for rhythmic classicism. Last Exit's reworkings of Timbaland/Dem 2 tic-beats meant that it had a relationship with a rhythmic psychedelia that was, then, still mutating Pop into new shapes. In the intervening period, of course, both hip hop and British garage have taken a turn for the brutalist, and Pop has consequently been deprived of any modernizing force. Timbaland's beat surrealism became water-treading repetition years ago, displaced by the ultra-realist Thuggish plod of corporate hip hop and the ugly carnality of Crunk; and 2 Step's 'feminine pressure' has long since been crushed by the testosterone-saturated bluntness of Grime and Dubstep. That skunk-fugged heaviness remains the antipodes of the Junior Boys' cyberian, etherealized, plaintive physicality; listening to the Junior Boys after Grime or Dubstep is like walking out of a locker room thick with dope smoke out onto a Caspar David Friedrich mountain. A lung-cleansing experience. (Significant also that those other ultra-heterosexual post Garage musics should have bred out the influence of House, while the Junior Boys return to it so emphatically.)

But the removal of rhythmic tricksiness perhaps also indicates something of the scale of the Junior Boys' Pop ambitions, which are best seen as the pionering of a New MOR rather than another attempt at New Pop. If, as Simon convincingly proposes on this Dissensus thread , there is no cutting edge, then it makes more sense to abandon the former margins and refurbish the middle of the road. The Junior Boys' songs have always had more in common with a certain type of modernist MOR - Hall and Oates, Prefab Sprout, Blue Nile, Lindsay Buckingham - than with any rock. Modernist MOR is the opposite of the discredited strategy of entryism: it doesn't 'conform to deform', it locates the alien right in the heart of the familiar. The problem with current Pop is not the predominance of MOR, but the fact that MOR has been corrupted by the wheedling whine of Indie authenticity. In any just world, the Junior Boys, not the drippy moroseness of James Blunt nor the earthy earnestness of KT Tunstall, would be the globally dominant MOR brand in 2006.

Ultimately, though, So This is Goodbye sounds more middle of the tundra than middle of the road. It's as if the Junior Boys' journey into North America Endless has continued beyond the late-night freeways of Last Exit. It's like the first LP's city lights and Edward Hopper coffee bars have receded, and we're taken out, beyond even the small towns, into the depopulated wildernesses of Canada's Northern Territories. Or rather, it's as if those wildernesses have crept into the very marrow of the record. In The Idea of North, Glenn Gould suggests that the North's icy desolation has a special pull on the Canadian imagination. You hear this on So This is Goodbye not in any positive content so much as in the Song's gaps and absences; the gaps and absences that make the Songs what they are.

Those crevices and grottoes seem to multiply as the album progresses. The second half of the album (what I hear as the 'second side'; one of the most gratifying things about So This is Goodbye is that it is structured like a classic Pop album, not an extras-clogged CD) diffuses forward motion into trails of electro-cumulae. The title track sets stately synths against the anti-climactic urgency of Acid House's Forever Now: the effect like running up a down escalator, frozen in an aching moment of transition. 'Like a child' and 'Caught in a Wave' immerse the agitated drive of the LP's signature arpeggiated synth in a vapour trail of opiated atmospherics.

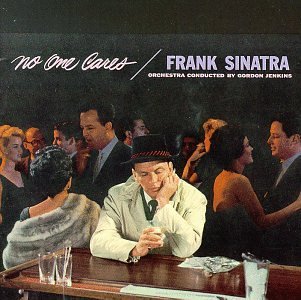

The reading of Sinatra's 'When No-one Cares' is the knot which holds together all of So This is Goodbye, a clue to its modernist MOR intentions (lines from the song - 'count souvenirs', 'like a child' - provide the titles for other tracks, almost as if the song is a puzzle the whole album is trying to solve). So This is Goodbye's songs bear much the same relation to high-energy as the late Sinatra's bore to big band jazz: what was once a communal, dance-oriented music has been hollowed out into a cavernous, contemplative space for the most solitary of musings. On the Junior Boys' 'When No-one Cares' beats are abandoned altogether, the track's 'endless night' lit only by the dying-star flares and stalactite-by-flashlight pulse of reverbed electronics.

The Junior Boys have transformed the song from the lonely-crowd melancholy of the original - Frank at the bar staring into his whisky sour, happy couples partying obliviously behind him (or in his imagination) - into a lament whispered in the wilderness, icy-breathed into the black mirror indifference of a Great Lake at midnight. It is as cosmically desolated as the Young Gods' version of 'September Song', as arctic-white as Miles Davis' Aura. 'When No-one Cares' is one of my favourite Sinatra songs, and I must have first heard it twenty years ago, but with the Junior Boys' version - which makes the catatonic stasis of the original's grief seem positively busy - it is as if I am hearing the words for the first time.

Sinatra's No-One Cares (which could have been subtitled: From penthouse to Satis House) was like Pop's take on literary modernism, an affect (rather than a concept) album, a series of takes on a particular theme - disconnection from a hyper-connected world - with Frank the ageing sophisticate adrift in the McLuhan wasteland of the late 50s, Elvis already here, the Beatles on the way (who is the 'no-one' who doesn't care if not the teen audience who have found new objects of adoration?), the telephone and the television offering only new ways to be lonely. So This is Goodbye is like a globalized update of No-One Cares, its images of 'hotel lobbies', 'shopping malls we'll never see again' and 'homes for sale' sketching a world in a state of permanent impermance (should we say precarity?). The songs are overwhelmingly preoccupied with leave-taking and change, fixated on doing things for the first or the last time. 'So This is Goodbye' is not the title track for nothing.

Sinatra's melancholy was the melancholy of mass (old) media technology - the 'extimacy' of the records facilitated by the phonograph and the microphone, and expressing a peculiarly cosmopolitan and urban sadness. 'I've flown around the world in plane/ designed the latest IBM brain/ but lately I'm so downhearted', Sinatra song on No-One Cares' 'I Can't Get Started'. Jetsetting is now not the privilege of the elite so much as a veritiginous mundanity for a permanently dispossessed global workforce. Every town has become the 'tourist town' alluded to in So This is Goodbye's final track, 'FM', because now at home everyone is a tourist, both in the sense of permanently on the move but also in the sense of having the world at their fingertips, via the net. If Sinatra's best records, like Hopper's paintings, were about the way in which the urban experience produces new forms of isolation (and also: that such mass mediated private moments are the only mode of affective connection in a fragmented world), then So this is Goodbye is a response to the cyberspatial commonplace that, with the net, even the most remote spot can be connected up (and also: that such connection often amounts to a communion of lonely souls). Hence the impression that, if Sinatra's 'When No-one Cars' was an unanswered call from the heartless heart of the Big Apple, then the Junior Boys' version has been phoned-in down a digital line from the edge of Lake Ontario. (Is it accidental that the term 'cyberspace' was invented by a Canadian?)

So this is Goodbye is a very travel sick record. It expresses what we might call nomadalgia. Nomadalgia, the sickness of travel, would be a complement to, not the opposite of, the sickness for home, nostalgia. (And what of the relation between nomadalgia and hauntology?) It's entirely fitting that the final track, 'FM', should invoke both 'a return home' and radio (not the only reference to that ghost-medium on the LP), since internet radio - with local stations available from any hotel in the world - is perhaps more than anything else the objective correlative of our current condition. A condition in which, as Zizek so aptly puts it, 'global harmony and solipsism strangely coincide. That is to say, does not our immersion in cyberspace go hand in hand with our reduction to a Leibnizian monad which, although 'without windows' that would directly open up to external reality, mirrors in itself the entire universe? Are we not more and more monads, interacting alone with the PC screen, encountering only the virtual simulacra, and yet immersed more than ever in the global network, synchronously communicating with the entire globe?'