May 22, 2008

'It's as if Brown reads your blog and wants to give you more material to work with!'

'It's as if Brown reads your blog and wants to give you more material to work with!,' writes a reader, of GB's latest, typically creepy, 'interactive' initiative. A classic example of Brownite digital doublethink, since 'Ask The PM' actually amounts to 'Listen To The PM', the comments facility having been disabled. But what gave the impression that Brown was bending over backwards to conform my description of him was this 'leaked' story that he has been mooted as the star of 'an Apprentice-style TV show for young politicians' - bringing him ever closer to the android President in Dick's Simulacra, who maintains power through the use of talent shows in the White House.

Meanwhile, Savonarola's diagnosis of the Italian left's malaise horribly parallels the situation in Britain, where New Labour's abandonment of class antagonism has both allowed class politics to be displaced into race, and enabled the Far Right to claim that it is now the only authentic representative of working class resentment:

- it is in losing its "duty to hate" (to quote Georges Labica's formulation) and its capacity to mould and direct inchoate fear & negativity in emancipatory directions, that the Left has given up its terrain to the Right (Alleanza Nazionale leader La Russa noted at their most recent conference that with the radical Left gone from parliament only they, the fascists, would stand up for the workers... - this is also Alemanno's line, and it seems to be working, nevermind the fact that they are in a coalition whose main effect will be to intensify "insecurity" in all its forms...).

May 13, 2008

No Future 2012

My presentation from yesterday's astonishingly successful Hauntology event at the Museum of Garden History. Thanks to everyone who attended....

Like The Fall piece below, the presentation is somewhat shorter than I had originally envisaged it, for the same reason.

(For Nick Kilroy)

(Photograph by Nick Kilroy, from Zabriskie Point)

There was no future, but it wasn’t like anyone expected.

2003. We’re wandering through the industrial spectres and overgrown dereliction of the Lea Valley.

It’s like the world has ended.

A world has ended here, in fact. But now nonhuman worlds teem and thrive amid the deserted factories and the waste-strata. Feral plants, algae so thick and artificial-looking you’d swear you could walk across the canal on it.

It is not a space that humans live in any more. But it is a space they explore. Most of us there that day had alternative names. K-space names. Nick K, Woebot, Heronbone.

Heronbone shows us a social history in the form of discarded packaging from defunct commodities. They call Heronbone the bard of Stratford – this is his patch, his Waste Land, and many of his words are assembled from discards, fragments of Grime lyrics recalled from the pirates, observations of insect colonies, flights of fancy prompted by this desolated space.

Nick K is ablaze with projects and schemes, his photographer’s eye captured by images every few minutes. Photography is a darker art than most people routinely suspect. The visionary photographer can find the image, but they cannot necessarily see everything that is recessed in it.

Most photographs act as mirrors, reflecting back the past into a frozen present. But some make contact with more mysterious dimensions of time. The "traces and clues of things to come". Futures bleeding back. Omens that can only be read retrospectively.

Sometimes there are signs but no-one who can read them.

2007. Other stalkers are moving through the scurf space we had traversed four years before.

Repetition, with a difference.

- "Right … Are you ready for the zone? From here on in it's pure Tarkovsky." And so it was. Light-industrial spaces, car-wrecker's yards, square-windowed studios, haulage depots. Then, a mile further on, we hit the fence.

The perimeter of the Olympic site is now secured by a plywood fence that is 10ft high, around four miles long, bright blue in colour and chinkless. In places it is double-banked, in others it is topped by razor- or barbed-wire. The ODA began its construction last spring, and the last sections were put into place in July.

The fence is a barrier designed to exclude not only access, but also vision. There are no viewing windows built into it, no portholes for the curious stakeholder. To see inside the zone, you must ascend a Stratford towerblock, hire a helicopter, or - the desideratum - visit the ODA's website, which provides stills of the construction process and mocked-up futuramas of the park (light-glinted buildings, sparkling water features, happy munchkin people).

Nothing again Nothing

The ‘mocked-up futuramas of the park’ surrender East London to the eventless horizon of the End of History, in which nothing happens forever.

Nothing happens, again and again.

Nothing happens. And every time it does, it’s announced with a press release.

In between our many visits to the Lea Valley in 2003 and Iain Sinclair and Robert Macfarlane’s expedition there in 2007, what happened, of course, was the awarding of the Olympic games to London. In that period, Nick K died, the photograph he took that day in 2003 now looking more than ever like an eerie pre-echo both of his own fate, and the fate of the whole area, which has now been consumed by the CGI-shadow of 2012.

The first signs of a coming non-event is always the CGI.

Ghost marketing

The CGI simulations that ring fence the Lea Valley project forward fake futures which will never arrive but which are immediately effective, already re-organising space in East London, already diverting resources from public to private. What this constitutes is a kind of negative hauntology, operating according to the familiar hype-dynamics of corporate capital. (Cybercapital relies on its own ethereal entities, of course.) We are not dealing with the spectres of lost possibilities, the ghosts of things that never happened, or the traces of forgotten events photoshopped out of the end of history. Instead, we are confronting the CGI-signs of a massive pseudo-event. A pre-scripted PR initiative disguised as an authentic happening.

According to some interpreters, 2012 is the year of the Mayan apocalypse. (Don’t worry, though, it’s scheduled for December, so it shouldn’t disrupt the Olympics.) The Olympics are now correlated with the end of time in quite a different way.

The arrival of the Olympics in China is not just a ratification of the Chinese regime, it’s also another moment in the end of History. 2008 is a symbolic threshold, much like 1989. Anti-modernist protests against China obscure the fact that the Olympics, like the People’s Republic Of China, is now inherently meshed with Global capital. 2008 will celebrate this integration, which may well presage a new mode of capitalism, in which authoritarian State control co-exists with PKD-like piratical capital. Victorian vampirism reformatted for cyberspace. The spectre of ultrapostmodernism, in which everything can be mass-replicated, but nothing new will ever be invented.

Memory Disorders

Both in Derrida’s original articulation of the concept, and its current recirculation, 15 years after Specters Of Marx, hauntology must be understood in relation to postmodernity. Postmodernism, in turn, has to be understood – as Jameson has taught us – as ‘the logic of late capitalism’. Postmodern temporality is captured by Fukuyama’s claim – everywhere officially disavowed, even by Fukuyma itself, even as, surreptitiously, it is universally accepted, operating as a kind of presupposition of the contemporary cultural unconscious – that we have reached the ‘end of History’. This is not only the conclusion of the process, but also the final cause to which everything has always been tending. End, then, in a double, appropriately Hegelian, sense: the terminus and the teleological goal.

The logic of late capitalism awaits the disintegration of the old Soviet bloc to find its fullest expression. Jameson’s great contribution was to have grasped the way in which, far from leading to an efflorescence of cultural innovation, the unprecedented dominion of capitalism over the globe and the unconscious would lead only to cultural situation given over to previously inconceivable levels of stagnation and inertia. Shorn of the confidence that an elite modernism could provide a revolutionary alternative to pacifying entertainment, no longer capable of believing that there was any form of detournement which could not in turn be re-incorporated and commodified, Jameson is the successor to both the Frankfurt School and the Situationists.

Jameson’s Marxism, in other words, had taken cognizance of Baudrillard’s critique. It was Baudrillard who anticipated the fusion of the opinion poll and reality TV in the seamless system of cultural ‘interactivity’which disarms any oppositional impulse by not only interpellating the consumer, but inducting them into its circuits. You decide. Text your response. Vote online. Join the debate. More or bore.

Jameson and Baudrillard understood that this user-generated content, together with the concomitant retreat of the cultural elite that has enabled it, would not lead to new kinds of creativity, but to pastiche and retrospection. Just as the capitalist language of ‘diversity’ is a cover for new modes of homogeneity. The duplicity that operates here is more a strange structural effect than any deliberate attempt at mystification, Jameson observes.

What Jameson calls the ‘nostalgia mode’ is one expression of this homogeneity. This remains one of Jameson’s most ingenious formulations – the nostalgia in question is not manifested in a psychological state but in a kind of unacknowledged formal reiteration.

Hauntology is the counterpart to this nostalgia mode. The preoccupation with the past in hauntological music could easily be construed as ‘nostalgic’. But it is the very foregrounding of temporality that makes hauntology differ from the typical products of the nostalgia mode, which bracket out history altogether in order to present themselves as new. Post postpunk, Indie’s equivalent of mock tudor.

The great sonic-theoretical contribution of The Caretaker to the discourse of hauntology was his understanding that the nostalgia mode has to do not with memories but with a memory disorder. The Caretaker’s early releases seemed to be about the honeyed appeal of a lost past: Al Bowlly’s aching croon in the Strand ballroom in prewar tearoom London, buried beneath the sound which constitutes something like the audio-correlate of hauntology itself: crackle. In veiling the past, crackle also makes the dimension of time audible. It is through this scratching of the scanner-lens that we can hear the time-wound, the chronological fracture, the expression of the sense, crucial to hauntology, that ‘time is out of joint’. Dyschronia.

As The Caretaker project has developed, though, it has become more about amnesia than memory. Theoretically pure anterograde amnesia is not about the inability to remember, so much as the incapacity to make new memories. The inability to distinguish the present from the past. The cultural pathology of a clipshow culture locked into endless rewind.

It as if The Caretaker has taken us from an Overlook hotel/ Dennis Potter themepark into a simulation of neurological disorder. Fragments of tunes providing minimal orientation in an labyrinth of abstract sound. Have you heard this before? You can never be sure.

Nostalgia For Modernism

But if there is one act which makes a case for the supreme pertinence of the concept of hauntology in relation to music today, it is Burial. Precisely because Burial deals with nostalgic longings, his music does not belong to the nostalgia mode. What you hear in Burial’s two LPs is a craving for a past which nevertheless appears irretrievably lost, veiled behind a relentless drizzle of crackle. Beyond the longing for a particular moment or a particular musical genre is a longing for the ceaseless forward motion of a culture which once appeared capable of infinite renewal, but which is now used up, involuted. The nostalgia for modernism resists the postmodern nostalgia mode.

Burial’s music is possessed by an extraordinary sense of space. This isn’t only a question of the production, which recalls Martin Hannett as much as King Tubby or Basic Channel. It is also about what the images the music evokes – very vivid audio-vignettes of South London this decade. Edward Hopper sound paintings of London after the rave. A city populated by ex-ravers gone to seed, like Nigel Cooke’s dejected vegetables. The long comedown after all the highs. Serotonin crash and anti-depressants. The spaces that are the correlates of such disaffected states. All day cafes and night buses glowing like diving bells in the undersea murk of the early hours. What haunts here is not only the past but possible futures. A drowned world catastrophe leaking back in time.

Haunting is about space as much as time – about the spaces where the time rift becomes perceptible, and, with Burial’s debut LP in particular, it was as if you were hearing double: hearing both the current dereliction and the former collective ecstasy. Flashbacks flaring in the gloom. What you are attuned to is a specific sense of place, as opposed to the ‘third place’ – the space that is neither home nor work, but which combines elements of both. Spaces of consumer convalescence which could be anywhere. Burial’s ‘In McDonald’s’ relocates the spatially-indifferent multinational capsule of the corporate franchise in a specific city: London, once again the capital of Capital. Once the sooty, smoggy centre of industrial capital, now the main hub of cybercapital. Open for business. Closed to almost anything else.

Is this burning an eternal flame?

The arrival of the Olympic flame in London a few weeks ago was a pseudo-event on the grandest of scales, given content only by its subversion.

The CGI shadows of 2012 already enclose us. Present time captured into the performance of pre-scripted PR opportunities forever.

But 2012 is an opportunity for dissent too. A focus for disaffection. Burial’s second LP includes a sample from Lynch’s INLAND EMPIRE.

‘I saw your light, it burns forever.’

You could hear this as the secret key to Burial’s whole sensibility. Like Lynch, Burial is attuned to the muffled, muted light – flashes of the numinous – that can be fleetingly glimpsed through the mundane. Distant lights, or lights that can be apprehended only from a distance.

Can we be guided by these lights, instead of by the Olympic flame, a symbol of a capital now more globalised than ever ever, the ultra bright strip lights drawing planetary destiny into an eternal shopping mall surrounded by a sweatshop?

The Place I Made The Purchase No Longer Exists

(Being an unfinished version of the paper I was due to present at The Fall conference in Salford last Friday, but which I couldn't attend due to family bereavement)

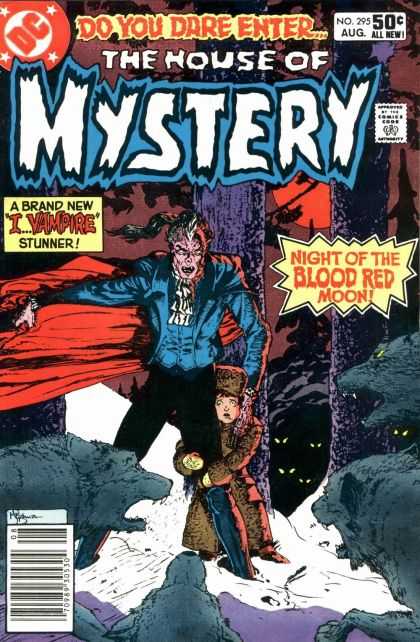

I keep bottles and comics stuffed by its head... Day by day The Moon gains on me

House Of Mystery cover from coverbrowser (thanks to Karl Kraft for the link)

Let’s start with the line itself:

The place I made the purchase no longer exists.

Already, even taken in isolation like this, the line is charged with associations, generic rather than specific. You think, perhaps, of portmanteau Horror flicks of the type which used to centre on an antique shop. The shop, of course, is on some side street that you haven’t noticed before. But today you find yourself drawn to the slightly shabby street, already strangely deserted though it is still only mid afternoon. Something about the items in the window of the antique shop draws your attention: on the face of it, there is nothing terribly odd about the wooden and glass objects on display, but something about them does not feel quite right, in a way that is slightly ominous but also enticing. You enter: the door triggers a loud bell, but the owner does not appear from the back of the shop yet. Your misgivings multiply, but they are easily overwhelmed by a sense of fascination. You are entranced by one particular object - an ornate, ebony mirror, perhaps, or a squat idol - when you’re shaken by a voice. The owner’s. He looks like Peter Cushing: kindly, eminently polite but with an edge of condescension and menace, an obsequious tempter. You are easily persuaded to buy the object to which you were drawn.

You leave. Things immediately go awry. You have to explain to what you laughingly call your loved one why you have bought home an object that is so … It makes them feel uneasy. They don’t want it in the house. You turn on them angrily. All of the seething spite and resentment in your failing marriage becomes focused through the Thing. You must keep it. At night, you start to feel that the object is mutely watching you, sizing you up. As the days go on, your marriage finally disintegrates. You’re left on your own with the Thing. It’s altering you, preparing the way for something terrible. It’s going to make you into its puppet, to use you as its eyes. You don’t want to look at it any more. You cover it with the dark sheet that the shopkeeper had wrapped it in. Sweating, delirious, you snap at strangers in the street who recoil aghast. You return to the street where the shop was situated. The same shabbiness. Except now there is no antiques shop. It doesn’t look like there ever had been. The two nondescript houses that had been either side of the shop remain, but the place you made the purchase no longer exists. It isn’t there, but the Thing – this portal to the Outside – remains. It’s yours now, forever. There is nowhere to return it to.

You might call a story like that clichéd. But formulaic would be a better word. Variations of this formula were used, not only in portmanteau Horror films, but fiction anthologies (of the type which New English Library used to turn out), TV programmes (as varied as The Twilight Zone and Tales Of The Unexpected), and also comics (the old EC titles, and their later imitations, such as DC’s House Of Mystery and Weird War).

The place I made the purchase no longer exists

When you hear the line, it carries all this with it. Superficially, you could construe it as an empty act of referencing, of postmodern playfulness, pastiche. Just a joke, a laff, commensurate with clip show conviviality. A knowing nod to what we used to watch from the End of History.

Sometimes The Fall have been heard in this spirit, increasingly so as the Mark E Smith persona has solidified, become a ‘national treasure’. Mark E Smith, the sort of no-nonsense bloke everyone would like to have a drink with. A fancied wit, still sharp, sarcastic - he’d keep you on your toes - but at the end of the day, he’s as pubbish and blokish as his one-time mentor John Peel, only with added prole cred. Mark E Smith, who gives his own life story to a culture in which biography has passively aggressively defanged fiction. See, we can explain it all now. True life tales. Nothing odd to see here.

This Mark E Smith is a doppelganger who has gradually all but replaced Mark E Smith the psychic and the schizophrenic, the ‘righteous maelstrom’, the dissonant vorticist transmitter who heard voices and spoke in tongues, the medium and media-channeler. The Mark E Smith who could make himself a riot of voices. People think of themselves too much as one person – they don’t know what to do with the other people that enter their heads.

Behind the autobiography, there’s a Weird tale in itself. Or rather a tale about how the Weird ends up mired in the mundane. The Man Whose Head Diminished.

Smith’s own fate looks like that of Romane Totale in reverse. If Totale was a cabaret entertainer become sorcerer, Smith is a lapsed sorcerer turned celebrated cabaret star, licensed fool on the BBC, licensed prole (in The Guardian). Totale was last seen in his Faery bunker, a tactical retreat that became a permanent exile, ritual facepaint devolving into Pierrot makeup dripping down his chin.

So R Totale dwells underground

Away from sickly grind

With ostrich headdress

Face a mess, covered in feathers

Orange red with blue black lines

And light blue plant heads

Smith foresaw it all, when he was still distilling televisionary psychic signals into Wyndham Lewis headline ticker-text. Foreseeing it, he told the same story many ways. At a certain point the powers will start to wane. The voices that speak through you will no longer make themselves heard. The words will not come. Your eyes will blink open and you will find yourself trapped in the most miserable reality, no longer able to make it take flight, or to yourself flee it. When all those egresses into other worlds recede, then this world will close around you, greasy with fried chicken fat, glossy with discarded celebrity trash, as seamless as a shopping mall, as interminable as a dreary videogame to which there is no level 2.

So now I sleep in ditches

And hide away from nosy kids

Smith the televisionary telepath foresaw it all, dreaded it, even as he could perhaps already feel it beginning even then. The signal coming through a scanner, increasingly dimly. So he flashed forward to these pictures of the maimed sorcerer-king become an addled old soak, mumbling stories for the amusement of laughing children. A gutted Icarus cast back to cursed earth, grounded in the gutter.

The wings rot and feather under me

The wings rot and curl right under me

After a while it will even seem to you that the derisive laughter is justified, that there was nothing there. That it was all a bit fanciful, that nothing really happened, or ever could.

The place I made the purchase no longer exists. When this line occurs, it is not a pallid act of citation, but an invocation and a triggering.

The formulas of Weird fiction function in a similar way – they are repetitions that carry with them some of the power of previous iterations. These fictions about portals are themselves portals, connecting to other fictions, but also to other worlds. Sometimes it is difficult to know the difference, difficult to establish the precise point that a fiction becomes a world, or that a fiction infects and infests a world.

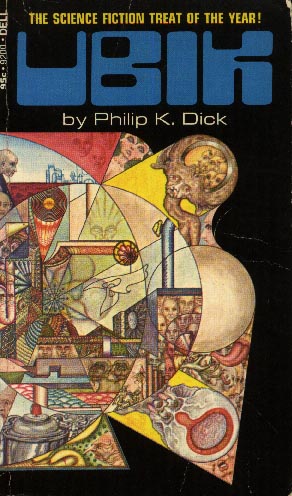

The notion of portals connecting worlds is crucial to the Weird, perhaps even definitional of it. As pre-eminent cases of Weird writers, let’s call up Lovecraft and Philip K Dick. Lovecraft’s innovation was to locate cosmic wonder and dread in his own New England backyard, and it was the juxtaposition of the abyssal and the quotidian that gave his fictions much of their thrilling charge. Ontological juxtaposition bring us close to the very essence of the Weird. There is no ‘Weird-in-itself’. The Weird, rather, consists precisely in the bringing together of Things which do not belong in the same place. The out of space and the out of time. This depends, of course, on a certain notion of what does belong: the ordinary world that will ultimately be invaded, its empiricist philosophy overthrown. The formal correlate of this ordinary world is a realism that will by the end of the tale be overwhelmed by a heightened cosmic delirialism, foaming with adjectives which, in their hyperbolic accretion, far from elucidating the weird object, make it more and more intractable.

What facilitates the aberrant mixes in Lovecraft’s tales are thresholds, places of contact between this world and others. Sometimes these thresholds are literal, albeit mystical, doorways; but more often than not the threshold is a book.

Dick’s fictions also turn upon the idea of multiple, incommensurate worlds. In Dick’s case, more so than Lovecraft’s, these worlds cannot be construed as different spaces, but as alternative realities, different ‘ontological options’. Viewed one way, these realities can appear to be epistemologically determined, the products of various technologies, influences or aptitudes – hallucinogenic drugs, the media, fiction itself, precognition. But the conundra Dick’s most powerful novels pose cannot be definitively resolved via any of these epistemological motivations. It is not the perception of reality that is warped in Dick’s fictions; it is reality itself. Or, better, any notion of ‘reality itself’ comes under threat, fractures into a multiplicity of worlds. As Brian McHale suggests in his Postmodernist Fiction, a text like Dick’s Ubik is best understood in ontological terms, as a kind of equivalent in fiction of an Escher painting: a tangle of overlapping incompatibilities.

McHale’s analysis of ‘postmodernist fiction’ places the notion of worlds – worlds within worlds, worlds next door – at its heart. This is where McHale’s account of postmodernist fiction crosses into the Weird as I have tried to outline it. But, whereas postmodernist fiction in its most anodyne and academic renditions ultimately collapses all worlds into texts, the Weird goes in the other direction: texts become worlds and portals between worlds. In Lovecraft, as I have already suggested, books open up holes in the mundane, points of weakness in the fabric of our world where outside forces can invade. For Lovecraft, make no mistake, there is no more dangerous activity than research. But where postmodernist fiction is usually associated with literary fiction, the Weird is typically disseminated in ‘pulp’ formats: magazines, paperbacks, comics, TV, b-movies.

Mark E Smith’s most distinctive texts echo both Lovecraft and Dick’s methodology. According to caricature, The Fall proffer a naturalism whose dreariness is leavened only by its humour. But it was only in their earliest mode that The Fall were comic naturalists, introducing an amphetamine-driven garage punk to the bingo halls, industrial estates and cracker factories of Northern England. By the time of Dragnet, The Fall were seeing the same Northern vistas through the filter of Weird fiction. Manchester tenements were now haunted by Roman spectres. Ghostly figures follow you down the Salford streets. ‘Impression Of J Temperance’ and ‘Jawbone And The Air Rifle’, from Grotesque and Hex Enduction Hour, compress Weird tales into a distorted, Northern rock. By now, Smith has repeated what Lovecraft had achieved – relocating the bizarre and the anomalous in his own neighbourhood. It is precisely the disjunction between the Manchester ‘estates that stick up like stacks’ and the ‘hideous replicas’ and haunted jawbones which generates the effect of Weirdness. Taken as a whole, Grotesque and Hex Enduction Hour are themselves weird objects: unplaceable, intractable, they are confections of things which should not belong together.

Epilogue: The alternative afterlife of Roman Totale

Wandering through the franchise coffee bars in the reconstructed centre of Manchester – the Arndale had been razed, his visions hadn’t led him astray there - Totale tentatively fingers the wounds. Things have got very confusing since they put him on the anti-psychotics. Once he had thought that the abrasions were the scars left from a tentaclectomy, imposed on him by a psycho mafia who wanted to block his Faery revolution. He hoped to overthrow the sickly grind, dreamed that he could preside over a kingdom of the grotesque and aberrant: hobgoblins in the shopping centres, golems stalking the council estates. But he had been assured that this was all a particularly florid delusion. The marks all over his body had been the result of a nasty self-harming habit. But things were better now.

They told him to stay away from the secondhand bookshops, to watch TV in moderation, and then only the right kinds of programmes - about DIY, interior design, diet, these were harmless, in fact the doctor encouraged him to watch shows such as these, hoping, he said, that they would encourage Mr Totale to take more interest in his appearance, to look after himself properly. But even when Totale did lapse and go hunting for the, it was only the old programmes, the ones he found cycling round on the cable channels, that triggered anything, phantom flashes, breakthroughs in a grey room. It used to be that he could easily find the psychic channel, wherever it was. But the new stuff was the opposite of a portal: a bad mirror, its surface cold and unyielding, capturing him in the world of his reflection. It and the drugs made it so he could no longer see himself as he once had.

Fragments of a voice. Absurdly high pitched, smurf-like. ‘Roman, Roman, don’t you know you’re dead?’

There’s no way back. The place I made the purchase no longer exists