April 29, 2008

The Wrong Man

|  |

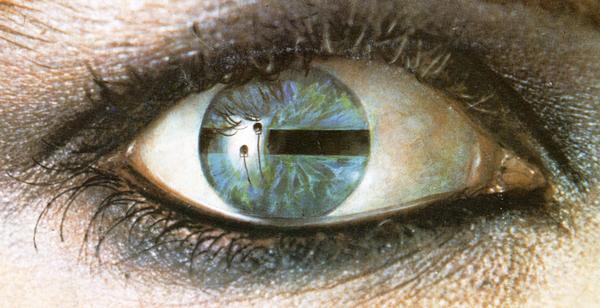

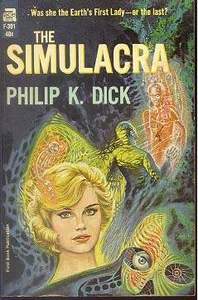

Gordon Brown’s appearance on American Idol a couple of weeks ago brings us ever closer to the situation described in Philip K Dick’s The Simulacra, in which advancement into the elite is achieved through talent shows held in the White House. It increasingly seems as if Dick did not so much predict the future as dream it in advance. The world of The Simulacra - in which politics has merged with talent competitions, in which drugs are the mandatory treatment for mental illness (the novel begins with the outlawing of psychoanalysis), and in which affective-telepathic aliens called papula are put in the service of salesmen of every type to directly manipulate the emotions of customers – looks eerily like our world, subjected to oneiric distortion, displacement and condensation.

Brown (extensively) and Dick (glancingly) both feature in Gordon Burn’s Born Yesterday: The News As A Novel, though they are not ever directly linked together. It is when he is reflecting on Kate McCann, that Burn mentions Dick’s Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep. “The conviction,” Burn observes, “given wide expression in the press and across the blogosphere, that Kate McCann was ‘hardly human’ in the cool and controlled way she behaved in the televised appeals for information about Madeleine and in the attention she gave to her clothes and hair and other aspects of her appearance in the face of catastrophe, clearly implied she must be implicated in some way in the disappearance of her daughter. The chief characteristic of androids is their lack of empathy. Because androids cannot feel empathy, their responses are either missing, or when faked, measurably slower than those of ‘genuine’ human beings.”

Me, I disconnect from you

It seems that Brown is the opposite case – eerily inhuman not because of a failure to exhibit empathy, but because of his incapacity to elicit it. Despite suffering personal tragedy in recent years, Brown has been singularly unable to make the public feel for him. This is one of many striking contrasts with his predecessor. If Blair was the papula, someone whose preferred medium is feelings (which can be both attitudinally certain yet conceptually nebulous), Brown is the gauche and unconvincing android – not so much ‘an analogue politician in a digital age’, as Burn has it, or rather not just that, but a man who can neither respond to, nor perform, the required emotional cues. There have been rumours, always emphatically denied, that Brown suffers from Asperger’s Syndrome (a condition, incidentally, with which the PKD-adoring, android-identifying Gary Numan, meanwhile, has recently been diagnosed).

“Watching Brown struggling to uncloud his countenance,” Burn writes, “became the recurring bad sight of the year: a car-crash moment waiting to happen at each and every photo-op.” Brown radiates discomfort in the way that Blair transmitted ease. Blair’s vacuous charisma compelled attention, even as it induced hatred; but Brown is unbearable to watch. There is a fundamental wrongness about Brown that raises a shudder, a faint disgust. Even the phrase “the Prime Minister, Gordon Brown” sounds wrong. It is always like that for a short period after the departure of a Prime Minister who has been in power for a long time, as you becomes used to the new incumbent being identified with the office, but with Brown, the sense of wrongness is more than a short term effect. There is something inherently wrong about Brown. His becoming Prime Minister is akin to a YouTube fantasist suddenly being propelled onto a stadium stage. He doesn’t belong. It shouldn’t have happened.

The hollow man and the hollowed man.

In the brief, false dawn of the ‘Brown bounce’, Brown profited because the loathing of Blair – stoked by the interminable self-congratulation of his protracted departure – was so great, and because, at that time, it was still possible to make the new PM’s inadequacies seem like strengths. According to the meta-spin – spin against spin, spin that denied that it was spin – Gordon’s dourness connoted all the substance and depth that Teflon Tony, the man without a shadow, had spirited way. Spin against spin, indeed: the slogan that Alistair Campbell had intended to be damning of Brown – “Not flash, just Gordon” – captured Brown’s appeal at the time of the bounce. In this initial period – Brown distancing himself from Bush while appearing on the steps of Downing Street with Thatcher – it seemed that Brown could repeat Blair’s performance of being a man for all, now with added Old Labour weight: he would be authentic oak in place of Tony’s shiny Teflon. But the only thing that is Old Labour about Brown is his discomfort with new media; as John Newsinger argued in this article in International Socialism, written at a time when Brown could still be made to appear more left-leaning that Blair, business-friendly Brown is a thoroughgoing market Stalinist. The smoke and mirrors which shrouded Brown’s early days as PM implied an Escheresque topology, in which Gordon could be both left and right at once. But whereas Blair – who presented the strange spectacle of a postmodern messianism - never had any beliefs that he had to recant on, Brown’s move from Presbyterian socialist to New Labour supremo has been a long, arduous and painful process of repudiation and denial. As Newsinger argued, “Whereas, for Blair, the embrace of neoliberalism involved no great personal struggle because he had no previous beliefs to dispose of, for Brown it involved a deliberate decision to change sides. The effort, one suspects, damaged his personality.” Blair was the Last Man by nature and inclination; Brown has become the Last Man, the dwarf at the End of History, by force of will. The android has replaced all his internal components, decommissioning and updating his instinctive and affective defaults, even constructing for himself some false memories. Tell us about your mother, Gordon.

- Brown told the Confederation of British Industry conference that “business is in my blood”. His mother had been a company director and “I was brought up in an atmosphere where I knew exactly what was happening as far as business was concerned”. He was, indeed he had always been, one of them. The only problem is that it was not true. As his mother subsequently admitted, she would never have called herself “a business woman”: she had only ever done some “light administrative duties” for “a small family firm” and had given up the job when she married, three years before young Gordon was even born. While there have been Labour politicians who have tried to invent working class backgrounds for themselves before, Brown is the first to try and invent a capitalist background. (John Newsinger, “Brown's Journey from Reformism to Neoliberalism”)

All of those confabulations and reinventions, and still, it doesn’t convince. It all looks wrong. Burn: “The separation between was he was saying and what his face was doing added up to a disturbing disjunction. The result was sinister. Pathological.” Blair, buffed up with Public School self-belief, the man without a chest (but with a media-friendly torso), the outsider the party needed in order to get into power, his joker hysterical face salesman-smooth; Brown’s implausible act of self-reinvention is what the party itself had to go through, his fake-smile grimace the objective correlative of Labour’s real state now: gutted, and gutless, its insides replaced by simulacra which once looked lustrous but now possesses all the allure of decade-old computer technology.

It wouldn’t be surprising if reports that Brown is depressed turned out to be true. Brown is tragic but not heroic: a Prufrock without the self-awareness and the humility, someone born to play the part of attendant lord now finding himself cast in the role of dithering Hamlet. Partly, his tragedy is the tragedy of desire realised. The role he seems most fitted to play – glowering just off centre stage, plotting behind the scenes – brought with it the rich, heady jouissance of resentment. Brown could relish this jouissance only while his official goal was thwarted; just as he could exert power without holding it, the shadow of the man without a shadow, the black dog forever at the hollow man’s heels, supping on every misstep and mishap.

But now Brown has exactly what he always wanted, and what could be worse than that? The melancholy that follows from finally achieving what that he has coveted all those years, from at last having his newly manicured fingers on the holy grail for the sake of which he has spent thirty years constructing a new identity and a new set of values, must be profound. Especially when the grail so quickly become a poisoned chalice. And not only in terms of Brown’s own libidinal economy, which must have crashed the moment that the previously unattainable was suddenly thrust into his grasp. There were external signs, too: some of the things which afflicted Brown appeared to be ill-fated coincidences, but some were entirely predictable consequences of neoliberalism’s indulgence of business. Brown’s accession to the premiership coincided with flood and pestilence, Biblical portents which - the pathetic fallacy notwithstanding – seemed to point to his wrongness as unequivocally as the Plague which beset Thebes when cursed Oedipus became king. And then there was Northern Rock and the credit crunch. And here is Gordon, always the wrong man at the wrong time.

Burn: “[A]s the months ticked past – the Brown bounce in the polls crashing by November into a 14-point deficit; the honeymoon souring, the smile hung on the damaged face muscles growing ever more beserk, ever more pleading; hair colour warmed up and toned down, hair newly volumised and shingled – Nixon is the politician Brown came to increasingly resemble.” Nixon: a figure who – from his sweating failure to perform against TV-slick Kennedy to his later Watergate tapings, deceptions and denials – seemed to shadow the work of Dick (in much the same way as Ballard’s best Sixties work was haunted by the assassination of JFK).

Dick’s fleeting appearance in Born Yesterday belies a deeper affinity between Burn’s methodology and Dick’s preoccupations. Born Yesterday had been framed in advance by Guardianistas as a commentary on the replacement of news with entertainment; very old news indeed to a reader of Dick or Baudrillard. Burn commented that he read Mark Lawson’s anticipatory gloss on a book that he had not yet completed with some anxiety: was he doing what Lawson said he was? Burn’s subtitle is of course deliberately ambiguous: what does that ‘as’ mean? Was Burn presenting the news in the form of a novel? Or was he showing that the news was already a novel? In the event, the subtitle is misleading: Burn’s book is not a novel, and neither is the news that is its subject. The wearisome descriptions of Born Yesterday as ‘blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction’ miss the point that Burn’s book does no such thing; there are few if any speculative leaps into the minds of characters, no fabricated events, and no real plot to speak of. Besides, as Dick and Baudrillard long ago realised – this is the very definition of the hyperreal – fact and fiction are complexly and by now intimately entangled with one another in a way that makes all talk of the ‘boundaries’ between the two ‘blurring’ seem somewhat quaint. Yet, at the same time, Born Yesterday is not a work of journalism or commentary. Burn manipulates news as a found object in a way that is reminiscent of Chris Marker: closing in on particular images, phrases and facts, rewinding and freeze-framing them, as he identifies – or is it induces? - correspondences, associations and echoes between figures and events that, to a casual eye, seemed to be connected only via the contingency of happenstance. Burn’s is a Gnostic art, and Born Yesterday is a work of hypnotic Hermetic ingenuity which suggests patterns that have been weaved, if they have been weaved at all, not by human conspiracies, but by stranger forces altogether.

April 22, 2008

Neo-imperialists fail to let off damp firework: the two year commemoration

If you speak post-structuralese, Euston was a "plateau" I suppose.

April 11, 2008

London litened

The free paper plague is infesting all areas of London life. From dawn to dusk... Arriving at the station in the morning, the Metro already piled up, waiting. Leaving the train, slipping into your somnambulent self, commuter character armour freezing into place, automatically making the Waste Land walk across London Bridge ('I had not thought that death had undone so many'), the way already blocked by reps proferring City AM. (London Bridge is a film set now (hyperreal city): there's barely a day where there isn't a camera crew or some out of work actors playing a bit part in some promotional pantomime.) And in the evening, rushing to escape the black hole of the city, you have to play live-action Pac Man with the London Lite and the londonpaper drones blocking the pavement every few yards. As if London needed people - poorly paid members of the city's immigrant subproletariat, at that - actually being employed to obstruct the pavement. In the train, the free papers are everywhere, their dull gloss a lurid temptation for the drained mind ... cut and pasted PR ... nothing happening forever ... cocaine celebrities ... a survey says... join in the debate... vote: more or bore... your texts... consume it and feel lulled and sullied... Semiotic parasites designed to prey upon hypnagogic drift. Weapons against the city's intelligence. Almost no-one reads books any more. London litened, littered, public transport desolated into a time waste land. Look around the carriage, snapshot of a MySpaced city: diversity without difference, homogeneity without communality - bodies reduced to claustrophobic zombie meat fighting for space, background hum of mutual hostility simmering, yet everyone is reading the same thing...

April 10, 2008

April 08, 2008

Calling Kafka

- 'There's no fixed exchange with the Castle, no central exchange which transmits our calls further. When anybody calls up the Castle from here the instruments in all the subordinate departments ring, or rather they would ring if practically all the departments – I know this for a certainty – didn't leave their receivers off. Now and then, however, a fatigued official may feel the need of a little distraction, especially in the evenings and at night and may hang the receiver on. Then we get an answer, but of course an answer that's a practical joke. And that's very understandable too. For who would take the responsibility of interrupting, in the middle of the night, the extremely important work that goes on furiously the whole time, with a message about his own private troubles? I can't comprehend how even a stranger can imagine that when he calls up Sordini, for example, it's Sordini that answers.'

The call centre experience distills the political phenomenology of late capitalism: the boredom and frustration punctuated by cheerily piped PR, the repeating of the same dreary details many times to different poorly trained and badly informed operatives, the building rage that must remain impotent because it can have no legitimate object, since – as is very quickly clear to the caller – there is no-one who knows, and no-one who could do anything even if they could. Anger can only be a matter of venting; it is aggression in a vacuum, directed at someone who is a fellow victim of the system but with whom there is no possibility of communality. Just as the anger has no proper object, it will have no effect. In this experience of a system that is unresponsive, impersonal, centreless, abstract and fragmentary, you are as close as you can be to confronting the artificial stupidity of Capital in itself.

Call centre angst is one more illustration of the way that Kafka is poorly understood as a writer of totalitarianism; a decentralized, market Stalinist bureaucracy is far more Kafkaesque than one in which there is a central authority.

- 'I didn't know it was like that, certainly,' said K. 'I couldn't know of all these peculiarities, but I didn't put much confidence in those telephone conversations and I was always aware that the only things of any importance were those that happened in the Castle itself.'

'No,' said the Superintendent, holding firmly onto the word, 'these telephone replies from the Castle certainly have a meaning, why shouldn't they? How could a message given by an official from the Castle not be important?'