April 30, 2007

So much to write, so many reflections on a fascinating week that included both the Lovecraft and the Speculative Realism events at Goldsmiths. But I seem to be the victim of a curse that prevents me writing at the moment. No sooner do I arrive back from London than I fall victim to some viral ailment. My head is beginning to clear, so expect a post on Lovecraft and Weird Realism in a day or two.

In the meantime, ask yourself this - which is worse: this or this?

On a lighter note*, this is one of the best sites devoted to television I've seen. Especially check out 'Nine Things Which Are Now Obligatory in Any Science-Fiction TV Series, Even Though Everybody’s Sick of Them'; it's forensic, particularly on the Dr Who theme music and on CGI.

*Actually, the site is only superficially light; Lawrence's observations on depression, for instance, are horribly acute.

April 20, 2007

Something got out from inside the story: Lynch's unhome videos

(Provisional thoughts on INLAND EMPIRE, based on one viewing - and once, in this case, is most certainly far from enough...)

Lynch's INLAND EMPIRE is full of holes.

A hole cigarette-burned into silk; a hole in the vagina wall leading to the intestine; a hole punctured into the stomach by a screwdriver; rabbit holes; holes in memory; holes in narrative: holes as positive nullity, gaps but also tunnels, the connectors in a hellish rhizome in which any part can potentially collapse into any other.

Both the cigarette burn hole and the hole in the vagina wall could serve as metonyms for the film's entire pyschotic geography. The hole in silk is an image of the camera and its double the spectating eye, whose gaze in INLAND EMPIRE is always voyeuristic and partial (we would see nothing if it weren't for the hole, yet what is behind the silk screen?) The hole in the vaginal wall, meanwhile, suggests a botched and demented Artaud-surgery aimed at transforming the organism into holey space. Holes within holes.

The best readings of INLAND EMPIRE have rightly stressed the film's labyrinthine, rabbet-warren anarchitecture. Yet the space involved is ontological, rather than merely physical. Mulholland Dr was perhaps the most compelling cinematic presentation to date of what Douglas Hofstadter calls a 'tangled hierarchy': a breaching of the distinction between ostensibly embedding and embedded ontological levels. With INLAND EMPIRE, world-haemorrhaging has become so accute that we can no longer talk about tangled hierarchies but a terrain subject to chronic ontological subsidence. 'Something got out from inside the story', we are told of the Polish movie which INLAND EMPIRE's film-within-a-film is remaking. In INLAND EMPIRE - which often seems like a series of dream sequences floating free of any ostensible reality, a dreaming without a dreamer (as all dreams really are) - no frame is secure, all attempts at embedding fail.

Each corridor - and there are many of Lynch's signature corridors in INLAND EMPIRE - is potentially the threshold to another world. Yet no character - the word seems absurdly inappopriate when applied to INLAND EMPIRE's fleeting figures, figments and fragments - can cross into these other worlds without themselves changing their nature. In INLAND EMPIRE, you are whatever world you find yourself in.

Reviews have confidently proclaimed that certain characters are 'prostitutes' or 'actresses'. Yet such rigid designations have little purchase on INLAND EMPIRE's vertiginous slippages, in part because the film continually prompts the questions: what is an actress? What is a prostitute? The short answer is that both actresses and prostitutes are (only) what they are for others. If INLAND EMPIRE insists upon the reversibility of the role of whore and actor - the prostitute is an actress, the actress is a prostitute - it is because in its worlds (as in ours), the condition of the actor-whore is universal: I AM WHAT I AM PAID TO BE. In the midst of one of the film's most disturbing sequences, shot, appropriately, on Hollywood Boulevard - Laura Dern - who may at this point be film star 'Nikki Grace' or film-within-a-film character 'Susan Blue' or Nikki Grace possessed by Susan Blue , (or ....) - declares 'I'm a whore', and her tone suggests hysteria, but also ecstasy and relief, as if the discovery has finally resolved her ontological inconsistency: So THAT'S what I am.

'Reflexivity without subjectivity', that perfect description of the unconscious, is exceptionally apt for INLAND EMPIRE's convolutions and involutions. Nikki Grace and the gaggle of other personae which Dern plays/ Grace hosts (or fragments into) put one in mind of the de-pyschologized avatars in Robbe-Grillet's novels - deprived of interiority, Nikki is a hole that we cannot help treating as an enigma, even though it is clear (to us, if not to her) that there is no hope of any solution. (Another question the film worries away at is the function of the proper name. What is to name something? So long as something has physical continuity are we justified in using the same name for it?) The temptation to ascribe depth, to resolve the film's ontological conundra epistemologically and psychologically (i.e. to attribute the film's to phantasms issuing from the deranged mind of one of the characters) is no doubt great, but must be resisted if we are to remain true to what is singular about the film. It is the film that is mad, not the characters in it.

As with Mulholland Dr, we are left with the impression that in INLAND EMPIRE it is Hollywood itself that is dreaming. Sunset Boulevard is one of INLAND EMPIRE's intertexts, and there's something both fitting and ironic about the fact that Lynch's latest meditation on 'the dream factory' should have been shot on Digital Video.

My fear before seeing INLAND EMPIRE was that Lynch's vision would dissipate in Digital Video's harsh and unforgiving light, its anti-expressionistic flatness. If anything, however, Lynch's sensibilty not only survives Digital Video, it reaches a new pitch through the use of the medium. This is in part because the use of Digital Video connotes reality: we are accustomed to seeing Digital Video used for home movies, for videos uploaded onto YouTube, for local news; its signature is the suggestion of minimal mediation. To see Lynch's worlds captured on digial video makes for a bizarre short-circuiting: as if we are witnessing a direct feed from the unconscious. In the age of YouTube and the cameraphone, all the world really is a film set. With INLAND EMPIRE, Lynch has produced a horror film for this culture of ubiquitous filming. (It becomes possible to imagine a future Lynch movie entirely filmed on a mobile phone.)

A word, also, for INLAND EMPIRE's brilliant 'sound design', by Lynch himself. The sound in INLAND EMPIRE - including an audacious and extensive deployment of Penderecki, which cannot but be heard as a quotation from The Shining - is superb throughout. I would definitely include in this - and here is the one point at which I find myself at variance with American Stranger's excellent piece on IE - the final sequence, which uses Nina Simone's 'Sinnerman'. Far from finding this sequence 'infuriatingly cute', it seemed to me like an infernal version of Dennis Potter - Pennies in Hell, perhaps.

April 18, 2007

Bring the Noise

- 'I began to realize a few years ago that it had moved beyond an attack on the idea that guitar rock alone had a special claim on seriousness, art status, rebellion, etc to the rejection of those ideals altogether—the whole complex of values to do with innovation, edge, danger, difficulty, subversion, disruption, notions of music as underground or oppositional, as either “art” (vision, expression, etc) or “folk” (social energy, collectivity, the real). This is all stuff we’re supposed to jettison, not just as something no longer applicable to the current situation, our scaled-down expectations, but as something that was never valid, was always fraudulent.'

Simon comes out fighting for the rockist cause in my interview with him about his new book. Check out his amazingly in-depth responses on hip-hop, the end of the black-white conversation in pop, and the relationship between his current nu-rockism and the earlier advocacy of jouissance and texture....

April 15, 2007

'Bleak and solemn...'

The temptation to visit the locations where films or television programmes were made is as difficult to resist as it is likely to lead to disappointment. We know perfectly well that the places as they appear on film or television do not really exist, that they are composites produced in the editing suite. Nevertheless, the pull is such that we will visit when we can, even at the risk of destroying our illusions.

In the case of the BBC’s M R James’ adaptations, the temptation to visit the locations is particularly powerful. Beyond any specific spectral entities, it is the landscapes – ‘bleak and solemn’, as James described them – that haunt (in) the BBC films. The films capture a seductive slowness proper to these nearly-deserted heaths and beaches, sublime in their sombre desolation. James’ characters are urban scholars who under-estimate the powers of this archaic and arcane terrain, with its ancient lore and laws, at their peril. They come from populous human centres into spaces that human beings have never managed to subdue.

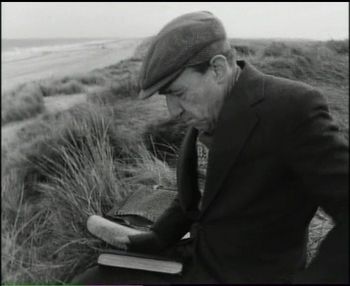

So, armed with information provided by Jamesian News, I go in search of the places used in the BBC versions of ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’ (directed by Jonathan Miller in 1968) and ‘A Warning to the Curious’ (directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark in 1972).

By the time they reached the screen, the locations had undergone a double displacement. In the stories, James, a regular visitor to Suffolk, used thin ciphers for two Suffolk places. ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’ is set in Burnstow, a transparent disguise for Felixstowe, then best known as a seaside resort, now renowned as the site of the largest container port in Britain. ‘A Warning to the Curious’ takes place in the town of Seaburgh, whose name is an easily cracked code for Aldeburgh (in the original manuscript of the story, James in fact wrote ‘Aldeburgh’ at one point, before striking out the ‘Alde’ and replacing it with ‘Sea’). Any visitor to Felixstowe will recognise James’ description of the old part of the town in ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’:

- Bleak and solemn was the view on which he took a last look before starting homeward. A faint yellow light in the west showed the links, on which a few figures moving towards the club-house were still visible, the squat martello tower, the lights of Aldsey village, the pale ribbon of sands intersected at intervals by black wooden groynes, the dim and murmuring sea.

James’ description was sufficiently precise that, last year, Wyrd Tales was able to reconstruct the lead character Parkin’s steps through the town. Similarly, for anyone who has visited Aldeburgh, James’ description of Seaburgh will inevitably recall the Suffolk town made famous in the twentieth century as the final home of Benjamin Britten:

- Marshes intersected by dykes to the south, recalling the early chapters of Great Expectations; flat fields to the north, merging into heath; heath, fir woods, and, above all, gorse, inland. A long sea-front and a street: behind that a spacious church of flint, with a broad, solid western tower and a peal of six bells.

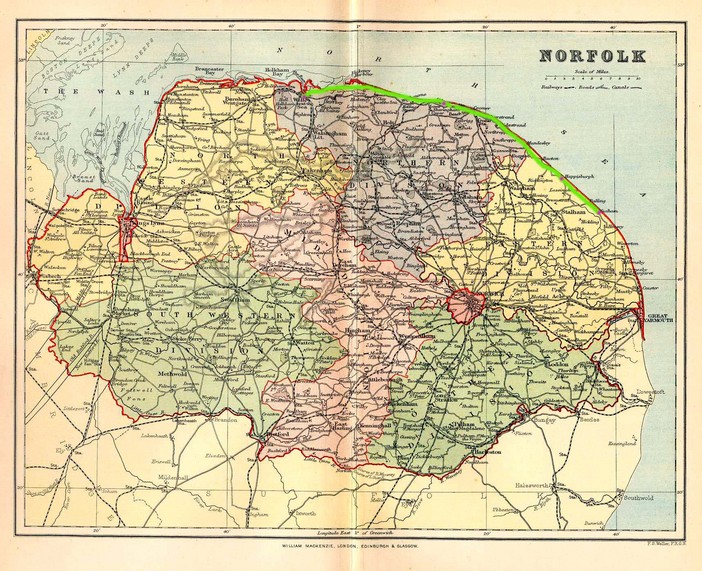

Yet Miller and Clark predominantly used locations not in Suffolk, but in Norfolk. (I say ‘predominantly’ because Miller filmed some sequences in the legendary Suffolk town of Dunwich. The crucial scene in which Parkin comes upon the whistle whilst wandering among the gravestones on a crumbling cliff-side were recognisably filmed in Dunwich, one of the most hauntological sites in England – a place, which as James’ namesake Henry noted while on a walking tour of Suffolk, consists now almost entirely of absence. Dunwich, once a thriving sea port, was nearly destroyed at a stroke by a storm in 1328; most of what remained was gradually claimed by the sea, so that today only a few houses and a single church are still standing, themselves threatened by the slowly voracious ocean. The town, with its Lovecraftian echoes - think not only of ‘The Dunwich Horror’, but also of the blighted port in ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’ - clearly deserves a post in its own right.)

Screen caps from the BBC films are on the left; my photographs are on the right. Since I was relying on my memory of the BBC films, some of the photographs correspond better than others with their counterparts from the television adaptations.

|  |

We arrive first at the village of Waxham, used by Miller in his ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’. If it is difficult to recognise specific locations from the TV version in the village, it is because Waxham has only a couple of recognisable landmarks, and Miller pointedly did not use these in his film. As Jamesian News’s correspondent Eddie Brazil observed, ‘there is hardly a village, just a few cottages, a neglected church with a ruined chancel, the remains of a 16th century house surrounded by a crumbling wall, sand dunes and the dim and distant murmuring sea.’ On the day in which we visited, the first stirrings of spring had brought the odd family to the beach, but this did little to disrupt the overwhelming atmosphere of isolation.

|

No doubt it was the very featurelessness of the Waxham beach which appealed to Miller when he was looking for locations at which to shoot ‘Whistle’. After all, James had described the beach where Parkin walked as a ‘long stretch of shore--shingle edged by sand, and intersected at short intervals with black groynes running down to the water’, a ‘bleak stage’ on which ‘no actor was visible’, and defined by ‘the absence of any landmark’.

|

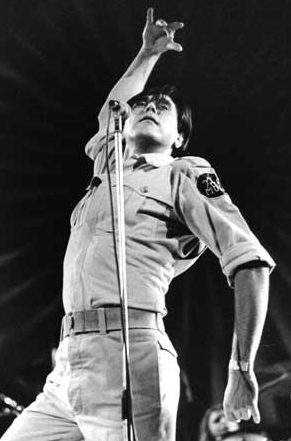

In Miller’s version, Parkin, played by a splendid Michael Hordern, is a crumbling logical positivist, his mind eroding as surely as the coastline, only far more quickly. In the manner of A J Ayer, Hordern’s Parkin is wont to dismiss the concept of life after death as devoid of meaning. Yet the stridency of his philosophical position is belied by the unsteadiness of his mumbling exposition.

The empty dunes and solitary heath land become an objective correlative for Parkin’s increasingly solipsistic mental state. Hordern, who was never better, conveys brilliantly Parkin’s withdrawal, his gestures and expressions suggesting conversational gambits and anecdotes that work far better when rehearsed in the theatre of his mind than they ever would in any inter-personal context. This is a man more at home with books than people. Only phantoms will interrupt his fantasies.

... the Dali-esque dunes, along which Paxton is chased by his spectral pursuer, become sheer patches of colour, nearly devoid of features ...

|

Up the coast a few miles from Waxham is the village of Happisburgh, the site of the church to which Peter Vaughan’s Paxton cycles at the beginning of Clark’s ‘A Warning to the Curious’. Happisburgh is a more substantial place than Waxham, though it, too, is menaced by the implacable North Sea. A display inside the church tells of how the village’s coastal defences are being bolstered by rocks quarried from Leicestershire. Yet coastal defences will surely only retard the process of erosion, not defeat it, especially when it is accelerated by global warming. With that in mind, it is hard not to feel, as one walks along the East Anglian coastline, that it is all destined to follow the fate of Dunwich. One has the uncanny experience of walking through spaces that, perhaps within only two generations, will persist solely as memories. Soon, this will all be an absence.

|

For the moment, the churchyard, with the muted gold of the beach stretching out beyond and below it, looks little different from when Clark filmed it in 1972. Watching the TV version, it seemed like the church stood on its own, far from any human habitation. Clark did well to create the impression that the church was an isolated spot. In fact, a busy-ish main road, a pub and a sizeable village, lie just outside the church grounds.

It is no surprise to find that the pagan symbol – referring ‘the legend of the Three Crowns’ which prompts Paxton’s visit – is nowhere to be found on the church. As you might have expected, this was a contrivance of the television production.

|

A few miles further up the coast, we arrive at Wells-next-the-Sea. By now we are a good three hours away from our starting point in Suffolk; although Suffolk and Norfolk are neighbouring counties, it would have been far quicker to drive to London than to Wells. In Wells, the small front looks out onto a quay, but the beach, accessible by a causeway, is set a mile or so back from here.

|

When you reach the end of the causeway, you immediately begin to recognise the very distinctive spaces that Clark used in his film. It is the proximity of pine woods to the beach that make this such an unusual setting. Their juxtaposition seems so eerie and oneiric that it almost seems that the dreaming land has garbled two incongruous features together.

|

Clark makes great use of the way in which the pine woods crowd up close to the long expanses of yellow sand. In the film, the Dali-esque dunes, along which Paxton is chased by his spectral pursuer, become sheer patches of colour, nearly devoid of features. As the sweating Paxton vainly attempts to flee his avenging adversary, it often seems that the two figures are the sole representational elements in an abstract space.

|

As I walked through the woods, I could not identify the hill where Paxton, working alone by starlight, disinterred one of the Three Crowns and attempted to re-bury it later. There were a few candidates, but none of them seemed quite right.

|

The warm weather meant that the woods were nowhere near as deserted as they were when Paxton made his lonely visit. And to approximate the twilight dread of Paxton’s furtive diggings, it would have been necessary to have been in the woods at sunset and after. Even in bright daylight, however, the woods have a quietly strange, shadowy atmosphere.

|

|

Returning down the causeway to the quayside, you soon come upon the Shipwright's pub. At first sight, I wasn’t sure that this was the inn where Paxton had stayed in the TV film, but when we returned home and were able to re-watch the film, it was obvious that this was the place. Sadly, it wasn’t possible to go inside the pub, since it has been in private hands for the last decade or so.

|

Back down the coast, a few miles south, and we arrive at Sheringham station, which doubled as Seaburgh railway station in the television film. It was here that Vaughan’s grim-faced autodidact arrives from the city; and from here that he takes the short trip to the neighbouring village where he digs up the crown. Opened in 1887 but long since closed as a mainline station, Sheringham station is now part of the heritage North Norfolk Line, on which one can take a 10-mile trip on a steam train. We were too late to travel on the train, but it was still possible to walk along the platform and look into the waiting room and booking hall, preserved so that they look much as they did in the 1972 film.

So did these visits destroy the illusion that the television films had constructed? In these cases, not at all. Miller and Clark’s adaptations make artful use of the Norfolk landscapes, but they do not distort them, with the result that walking these landscapes after seeing the films is not a deflationary, but an uncanny, experience.

April 13, 2007

Mitigated nostalgia and excessive presence

(After the Easter hiatus, the first of two posts about cultural memory.)

Since I wrote about the first episode of Life on Mars, it is fitting that I should return to the show to make a few remarks on the occasion of its final episode this week.

In the end, the SF elements of Life on Mars consisted solely in an ontological hesitation: is this real or not? As such, Life on Mars fell squarely into Todorov's definition of the Fantastic as that which hesitates between the Uncanny (that which can ultimately be explained naturalistically) and the Marvellous (that which can only be accounted for in supernatural terms). As is well known, the predicament that Life on Mars explored was: is Sam Tyler (John Simm) in a coma, and the whole 1970s world in which he is lost some kind of unconscious confabulation? Or has he, by some means not yet understood, been transported back into the real 1973? The show maintained the equivocation until the end (the final episode was ambivalent to the point of being cryptic).

Simm has wryly observed that the show's central conceit lets the production of the hook. If Tyler was in a coma, then any of Life on Mars's historical inaccuracies could be explained away as gaps in the character's recollections of the period. No doubt the enjoyment of Life on Mars derived from its imperfect recollection, not of 1973 itself, but of the television of the 1970s. The programme was mitigated nostalgia, I Love 1973 as a cop show. I say cop show, because it is clear that the SF elements of Life on Mars were little more than pretexts; the show was a meta-cop show rather than meta-SF. The time travel conceit permitted the showing of representations which would otherwise be unacceptable, and beneath the framing ontological question (is this real or not?), there was a question about desire and politics: do we want this to be real?

As the avatar of the present, Sam Tyler became the bad conscience of the 70s cop show, whose discontent with the past permitted us to enjoy it again. Simm, as the modern, enlightened 'good cop', was less the anti-type of antedeluvian 'bad cop' Gene Hunt than the postmodern disavowal which made possible our enjoyment of Hunt's invective and violence. Hunt, played by Philip Glenister, became the show's real star, beloved of the tabloids who adored quoting his streams of abuse, carefully constructed by the writers so that they could come across as comic rather than inflammatory. Hunt's 'no-nonsense policing' was presented with enough 'grit' to make us wince, but never so much violence that it would invoke disgust. (In this respect, the programme was the cultural equivalent of a blow to a suspect that would not show up under later medical examination.)

Undoubtedly, although perhaps unintentionally, the show's ultimate message was reactionary; in the end, rather than Tyler educating Hunt, it was he would come to an accommodation with Hunt's methods. When, in the final episode, Tyler is faced with a choice between betraying Hunt or staying loyal (at this point in the narrative, it appears that Tyler's betrayal of Hunt is the requisite price Tyler must pay in order to return to 2007), this also became a choice between 1973 and the present day that amounted to a decision, not about collar lengths or other cultural preferences, but about policing styles. Audience sympathy is managed such that, however much we disapprove of Hunt, we are never supposed to lose faith in him, so that Tyler's betrayal seemed far worse than any of Hunt's many misdemeanours. Tyler's (apparent) return to 2007 underscores this by presenting the modern environment as sterile, drearily worthy, ultimately far less real than the rough justice of Hunt's era (an interesting comment on the hyperreal dullness of Blair's Britain). Modern wisdom ('how can you maintain the law by breaking the law?') is set against Hunt's renegade-heroic identification of himself with the law ('I am the law, so how can I break it?') The deep libidinal appeal of Hunt derives from his impossible duality as upholder of the Law and he who enjoys unlimited jouissance. The two faces of the Father, the stern lawgiver and Pere Jouissance, resolved: the perfect figure of reactionary longing, a charismatic embodiment of everything allegedly forbidden to us by 'political correctness'.

In my first post on Life On Mars I mentioned Baudrillard's remarks that computers do not have memory because they cannot forget. (Ironically - or appropriately - I had forgotten that I had previously made this connection, and was about to begin this post with the same Baudrillard reference.)

Digital memory can be damaged or incomplete, but this is not the same as forgetting, which is not in any real sense the opposite of remembering. Personal or cultural memory is inherently 'incomplete', because there is no memory without distortion and embellishment.

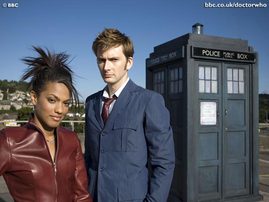

|  |

In any case, these observations came to mind the other day when I was wondering if the new series of Dr Who, which continues to frustrate and disappoint, will be remembered as the old one was. In the period before re-runs on digital channels and VHS re-issues, the old show existed only in the form of memory, of course. In the case of many of the episodes from the 1960s, long since wiped by the BBC, this remains so. Well, not quite: the soundtracks to all of the old episodes survive, even though the images are missing. (This allowed the BBC to reconstruct the recently re-issued Patrick Troughton adventure, The Invasion, using Cosgrove Hall animations for the two episodes that have not been recovered.) But in the pre-VHS period, Dr Who persisted as memory, perhaps augmented by the Target novelisations which, after a while, became indistinguishable from the experience of watching the shows themselves (with the result that there are certain adventures from the early 70s that I am no longer sure if I saw at the time or not). These augmented recollections, these re-dreamings, inevitably had a richness that the actual episodes, when they were available again, could not match, damaging the reputation of the previously celbrated early 70s adventures.

The current Dr Who is the victim of a syndrome that is pretty much the opposite of this: hyped to death by the BBC (the ludicrously laudatory Dr Who Confidential would have you believe that the new Dr Who is practically the most sophisticated drama programme the BBC has ever made), repeated during the week on digitial channels, available almost immediately on DVD, it suffers from excessive presence. The relentless sub-Buffy smart alecry and tiresome pop culture references (this week it was Harry Potter) root this Dr Who firmly in the early Twenty-First century, time traveller as Last Man...

In the midst of a PR maelstrom, the programme itself looks increasingly slight (that slightness is emphasised all the more by Murray Gold's histrionic music, such a contrast with the Radiophic Workshop's Electronic Weird). Like so much contemporary television, Dr Who seems like an advert for itself: twitchily neurotic in its desire to please, over-excitable in its pacing, it is always trailing the next grafication, never lingering long off to enough to provide much enjoyment.

If this Dr Who will be remembered, it will not be remembered in the same way that the old one was, precisely because memory will no longer required. The programme has been memorialized in advance, so there is no need for us to remember at all.

April 11, 2007

April 10, 2007

Apologies, but, unlike Owen, I can't declare an end to the holidays: I still have visitors. But I'm taking a hauntological/ M R James trip tomorrow. I hope to be able to report back on that on Thursday.

April 02, 2007

The mysterious concept «хонтология»

k-punk gets a mention on this round-up of Brit blogs in the Russian magazine Big City.

Running the piece through this online translator yields the amusing results that automatic translation programmes usually produce. Most notable is the description of Ian Penman (Иэна Пенмана) as 'an outstanding musical journalist with scandalous customs'. Of the Pillbox, the translation continues:

'All this is written very impulsively — it is visible, that the person takes things to heart. Here last incident: Пенман has furiously thrown on colleague Sajmona Rejnoldsa (other most outstanding English musical critic, whose marginal notes (blissout.blogspot.com) too should find time), finding out values of mysterious concept «хонтология». Soon after this enchantling skirmish Пенман has suddenly broken off and does not write one and a half month.'

Also check the description of Beyond the Implode's Martin, who writes 'with such furious humour that profanation turns out enough вдохновенная...'

April 01, 2007

'time for the dead to have a word with the living'

A number of threads that have come up here recently - hauntology, the collapse of the public sphere, the Lehrstucke, Lee Edelman-type Queer theory, the end of music - coalesce in Ultra-red's Public Record project, an internet 'archive of audio-actions' made by Ultra-red and their allies.

Ultra-red’s own account of the project is explicitly hauntological. ‘One could reductively interpret Public Record as an archive of death: a death of social movements, a death of coalitions, campaigns, utopias, struggles, and a death of socialism. Such an interpretation would profoundly miss the point. Not to mention that such a reading would be only possible were the archive not used. In listening, one invariably gets caught up in the record and its political effects. The record is a remainder.’ A remainder that is also a reminder, a reinvocation, the calling up of a ghost of a chance.

Witness, also, their rationale for the great AIDS Uncanny series (alternate title: 'time for the dead to have a word with the living'): 'THE AIDS UNCANNY series examines AIDS activist strategies of the past. Artists interrogate the record of those actions and practices, listening for some remainder haunting the present, to act as a kernel for a new radicality. Do we wait around for anger, or do we work within our existing affective spaces? This is the art of a broken silence.'

Silence and Death are the hauntological twins around which much of the material on Public Record is organised. Silence and Death were doubled in the old AIDS activist cry, 'Silence=Death', and various recordings of that chant reverberate throughout the AIDS Uncanny series. The equation 'Silence=Death' can only be broken if the dead, those condemned to silence, gain a voice; and if the voices of the living can become media through which the dead, the absent, can speak.

The material on Public Record circulates around a number of (interlocking) themes - AIDS, poverty, immigration, Queer politics. The treatment of these themes by 'sound artists' might invite a weary groan; you might expect a double dose of worthiness. Yet Ultra-red deliver on their promise to produce a 'Queer Electronica', where 'Queer' defiantly regains its associations of strange, uncanny, abnormal. Ultra-red are suspicious of a queer poltics which orientates itself around the imperative of normalising same-sex relations, a politics whose horizons are marked by the pursuit of the once derided goal of 'gay marriage'. Even though there is an engagement with popular forms, Ultra-red refuse populism, both aesthetically and politically.

When XLR8R asked Ultra-red's Dont Rhine last year 'What do you want people to do with this record?', he replied, 'Radical, ecstatic, critical bodily engagement. Our struggles begin on the surface of the skin. Spare us the old cliches about "intelligent dance music". A Silence Broken sees body music as a site for critical engagement'. Of course, we've all read self-serving rationales for sound installations claiming to 'engage the body' only to bore it rigid. But it is Ultra-red's relationship to dance music, specifically to House, that sets them far apart from sound art aridity. This is no vampiric 'intelligent' take on dance music (which no matter how much blood it sucks, remains bloodless), but precisely a hauntological rendition: a series of seances summoning the spirit of collective struggles and collective ecstasies. The centrepiece of last year's An Archive of Silence, part of the AIDS Uncanny series, is a spectral channeling of Mr Fingers' Acid classic 'Can you feel it?' The question - unspoken on both the original, instrumental track and on the Ultra-red version - now assumes hauntological/ political significance. Can you (still) feel it? How many who danced to this Acid classic when it came out twenty years ago have since died in the AIDS epidemic, which continues to spread in the US, where federal AIDS dollars are diverted to Christian fundamentalists preaching that the virus is God's punishment? The invocation of House - an American cultural site that was both gay and black - is especially poignant given that, according to Ultra-red, an astonishing '45% of all African American men who have sex with men are HIV positive, 70% of whom don't know their HIV status. Contributing to today's AIDS crisis is the fact that one out eight Americans live in poverty.' From the point of view of AIDS, neo-liberalism is a wonderful thing.

The Public Record is not intended to be a faithful record, a mere capturing of the empirical. Indeed, like Chris Marker, Ultra-red pose the question of what is it to document or record an event; they appear to share Marker's conviction that it is only through processes of estrangement that sound and images can attain truth or political efficacy. 'Without that infidelity between mouth and ear, a slippage invariably invoking an other, there can be no politics.' Hence there is no earnest breast-beating here, no injuction towards 'clear communication'... What is inspiring is the dissolution of established forms; Ultra-red's establishing of a continuum between House, electro-acoustic and spoken word does to music what Marker, Curtis and Keillor do to the documentary. (Especially recommended is the first volume of the AIDS Uncanny series, A Silence Broken, which actually includes a track called 'Repetition Compulsion' by Death Drive.) Cage's dictum, 'this is music anyone can make, all you have to do is listen', becomes a licence for cyberpunk production and militancy, a challenge to use recording technologies and the net's means of replication to engender new forms.

Rhine's answer to XLR8R's question 'How does electronic music convey political messages?' is a model riposte to Stekelmanism*:

'Political messages are not the point. I, personally, have little interest in communicating a political point in a piece of music. Rather, I am more interested in how music already activates us socially, sexually, intellectually, aesthetically. I see all these modes of being - structures of feeling if you will - as having political currency. It is not the case that our politics merely reproduce our modes of being. Rather, it is through these that the conditions for our politics are reproduced. If our art insists on the disavowal of politics, then we get the politics that disavowal makes possible. Today, that politics is fascism.'

*Stekelmanism (a.k.a. 'Man Who Fell Asleepism'): insistence on the separation of culture and politics; hard ideological labour for neo-liberalism; militant aesthetic complacency; middle-brow common-sense; anti-intellectualism; compulsory frivolity, esp. prevalent amongst Anglo-Media types, exemplified by responses on these two comments thread, and by these sorry cartoons.