April 15, 2007

'Bleak and solemn...'

The temptation to visit the locations where films or television programmes were made is as difficult to resist as it is likely to lead to disappointment. We know perfectly well that the places as they appear on film or television do not really exist, that they are composites produced in the editing suite. Nevertheless, the pull is such that we will visit when we can, even at the risk of destroying our illusions.

In the case of the BBC’s M R James’ adaptations, the temptation to visit the locations is particularly powerful. Beyond any specific spectral entities, it is the landscapes – ‘bleak and solemn’, as James described them – that haunt (in) the BBC films. The films capture a seductive slowness proper to these nearly-deserted heaths and beaches, sublime in their sombre desolation. James’ characters are urban scholars who under-estimate the powers of this archaic and arcane terrain, with its ancient lore and laws, at their peril. They come from populous human centres into spaces that human beings have never managed to subdue.

So, armed with information provided by Jamesian News, I go in search of the places used in the BBC versions of ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’ (directed by Jonathan Miller in 1968) and ‘A Warning to the Curious’ (directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark in 1972).

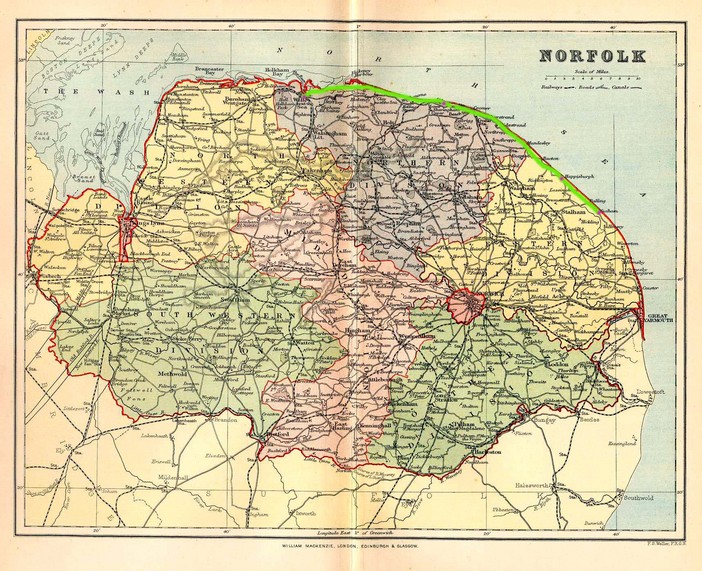

By the time they reached the screen, the locations had undergone a double displacement. In the stories, James, a regular visitor to Suffolk, used thin ciphers for two Suffolk places. ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’ is set in Burnstow, a transparent disguise for Felixstowe, then best known as a seaside resort, now renowned as the site of the largest container port in Britain. ‘A Warning to the Curious’ takes place in the town of Seaburgh, whose name is an easily cracked code for Aldeburgh (in the original manuscript of the story, James in fact wrote ‘Aldeburgh’ at one point, before striking out the ‘Alde’ and replacing it with ‘Sea’). Any visitor to Felixstowe will recognise James’ description of the old part of the town in ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’:

- Bleak and solemn was the view on which he took a last look before starting homeward. A faint yellow light in the west showed the links, on which a few figures moving towards the club-house were still visible, the squat martello tower, the lights of Aldsey village, the pale ribbon of sands intersected at intervals by black wooden groynes, the dim and murmuring sea.

James’ description was sufficiently precise that, last year, Wyrd Tales was able to reconstruct the lead character Parkin’s steps through the town. Similarly, for anyone who has visited Aldeburgh, James’ description of Seaburgh will inevitably recall the Suffolk town made famous in the twentieth century as the final home of Benjamin Britten:

- Marshes intersected by dykes to the south, recalling the early chapters of Great Expectations; flat fields to the north, merging into heath; heath, fir woods, and, above all, gorse, inland. A long sea-front and a street: behind that a spacious church of flint, with a broad, solid western tower and a peal of six bells.

Yet Miller and Clark predominantly used locations not in Suffolk, but in Norfolk. (I say ‘predominantly’ because Miller filmed some sequences in the legendary Suffolk town of Dunwich. The crucial scene in which Parkin comes upon the whistle whilst wandering among the gravestones on a crumbling cliff-side were recognisably filmed in Dunwich, one of the most hauntological sites in England – a place, which as James’ namesake Henry noted while on a walking tour of Suffolk, consists now almost entirely of absence. Dunwich, once a thriving sea port, was nearly destroyed at a stroke by a storm in 1328; most of what remained was gradually claimed by the sea, so that today only a few houses and a single church are still standing, themselves threatened by the slowly voracious ocean. The town, with its Lovecraftian echoes - think not only of ‘The Dunwich Horror’, but also of the blighted port in ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’ - clearly deserves a post in its own right.)

Screen caps from the BBC films are on the left; my photographs are on the right. Since I was relying on my memory of the BBC films, some of the photographs correspond better than others with their counterparts from the television adaptations.

|  |

We arrive first at the village of Waxham, used by Miller in his ‘Whistle and I’ll Come to You’. If it is difficult to recognise specific locations from the TV version in the village, it is because Waxham has only a couple of recognisable landmarks, and Miller pointedly did not use these in his film. As Jamesian News’s correspondent Eddie Brazil observed, ‘there is hardly a village, just a few cottages, a neglected church with a ruined chancel, the remains of a 16th century house surrounded by a crumbling wall, sand dunes and the dim and distant murmuring sea.’ On the day in which we visited, the first stirrings of spring had brought the odd family to the beach, but this did little to disrupt the overwhelming atmosphere of isolation.

|

No doubt it was the very featurelessness of the Waxham beach which appealed to Miller when he was looking for locations at which to shoot ‘Whistle’. After all, James had described the beach where Parkin walked as a ‘long stretch of shore--shingle edged by sand, and intersected at short intervals with black groynes running down to the water’, a ‘bleak stage’ on which ‘no actor was visible’, and defined by ‘the absence of any landmark’.

|

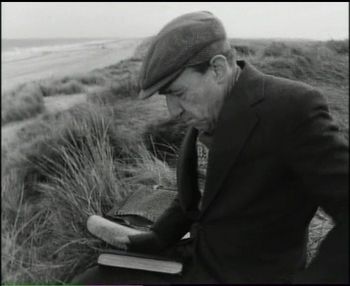

In Miller’s version, Parkin, played by a splendid Michael Hordern, is a crumbling logical positivist, his mind eroding as surely as the coastline, only far more quickly. In the manner of A J Ayer, Hordern’s Parkin is wont to dismiss the concept of life after death as devoid of meaning. Yet the stridency of his philosophical position is belied by the unsteadiness of his mumbling exposition.

The empty dunes and solitary heath land become an objective correlative for Parkin’s increasingly solipsistic mental state. Hordern, who was never better, conveys brilliantly Parkin’s withdrawal, his gestures and expressions suggesting conversational gambits and anecdotes that work far better when rehearsed in the theatre of his mind than they ever would in any inter-personal context. This is a man more at home with books than people. Only phantoms will interrupt his fantasies.

... the Dali-esque dunes, along which Paxton is chased by his spectral pursuer, become sheer patches of colour, nearly devoid of features ...

|

Up the coast a few miles from Waxham is the village of Happisburgh, the site of the church to which Peter Vaughan’s Paxton cycles at the beginning of Clark’s ‘A Warning to the Curious’. Happisburgh is a more substantial place than Waxham, though it, too, is menaced by the implacable North Sea. A display inside the church tells of how the village’s coastal defences are being bolstered by rocks quarried from Leicestershire. Yet coastal defences will surely only retard the process of erosion, not defeat it, especially when it is accelerated by global warming. With that in mind, it is hard not to feel, as one walks along the East Anglian coastline, that it is all destined to follow the fate of Dunwich. One has the uncanny experience of walking through spaces that, perhaps within only two generations, will persist solely as memories. Soon, this will all be an absence.

|

For the moment, the churchyard, with the muted gold of the beach stretching out beyond and below it, looks little different from when Clark filmed it in 1972. Watching the TV version, it seemed like the church stood on its own, far from any human habitation. Clark did well to create the impression that the church was an isolated spot. In fact, a busy-ish main road, a pub and a sizeable village, lie just outside the church grounds.

It is no surprise to find that the pagan symbol – referring ‘the legend of the Three Crowns’ which prompts Paxton’s visit – is nowhere to be found on the church. As you might have expected, this was a contrivance of the television production.

|

A few miles further up the coast, we arrive at Wells-next-the-Sea. By now we are a good three hours away from our starting point in Suffolk; although Suffolk and Norfolk are neighbouring counties, it would have been far quicker to drive to London than to Wells. In Wells, the small front looks out onto a quay, but the beach, accessible by a causeway, is set a mile or so back from here.

|

When you reach the end of the causeway, you immediately begin to recognise the very distinctive spaces that Clark used in his film. It is the proximity of pine woods to the beach that make this such an unusual setting. Their juxtaposition seems so eerie and oneiric that it almost seems that the dreaming land has garbled two incongruous features together.

|

Clark makes great use of the way in which the pine woods crowd up close to the long expanses of yellow sand. In the film, the Dali-esque dunes, along which Paxton is chased by his spectral pursuer, become sheer patches of colour, nearly devoid of features. As the sweating Paxton vainly attempts to flee his avenging adversary, it often seems that the two figures are the sole representational elements in an abstract space.

|

As I walked through the woods, I could not identify the hill where Paxton, working alone by starlight, disinterred one of the Three Crowns and attempted to re-bury it later. There were a few candidates, but none of them seemed quite right.

|

The warm weather meant that the woods were nowhere near as deserted as they were when Paxton made his lonely visit. And to approximate the twilight dread of Paxton’s furtive diggings, it would have been necessary to have been in the woods at sunset and after. Even in bright daylight, however, the woods have a quietly strange, shadowy atmosphere.

|

|

Returning down the causeway to the quayside, you soon come upon the Shipwright's pub. At first sight, I wasn’t sure that this was the inn where Paxton had stayed in the TV film, but when we returned home and were able to re-watch the film, it was obvious that this was the place. Sadly, it wasn’t possible to go inside the pub, since it has been in private hands for the last decade or so.

|

Back down the coast, a few miles south, and we arrive at Sheringham station, which doubled as Seaburgh railway station in the television film. It was here that Vaughan’s grim-faced autodidact arrives from the city; and from here that he takes the short trip to the neighbouring village where he digs up the crown. Opened in 1887 but long since closed as a mainline station, Sheringham station is now part of the heritage North Norfolk Line, on which one can take a 10-mile trip on a steam train. We were too late to travel on the train, but it was still possible to walk along the platform and look into the waiting room and booking hall, preserved so that they look much as they did in the 1972 film.

So did these visits destroy the illusion that the television films had constructed? In these cases, not at all. Miller and Clark’s adaptations make artful use of the Norfolk landscapes, but they do not distort them, with the result that walking these landscapes after seeing the films is not a deflationary, but an uncanny, experience.

Posted by mark at April 15, 2007 10:12 PM | TrackBack