January 31, 2006

Is Pop Undead?

|  |

If there is a current coalescence of fascination around hauntology, there is also a mounting anxiety about the death, dearth, end of Pop. A few examples: this atrocious piece on the 'death of black music' (significant only for the statistics it cites), Simon's 05 round-up for Frieze, a number of recent threads on Dissensus, including this one and this one. The suspicion is inescapable: part of the reason why hauntology should appeal to us so much now is that, unconsciously, and increasingly consciously, we suspect that something has died.

Nothing lasts forever, of that I'm sure

Announcements of the demise of pop are nothing new of course. And there any number of reasons to be sceptical about the language of 'death' and morbidity (not least because it concedes too much to the vitalist valorizations of life). The fact is that nothing ever really dies, not in cultural terms. At a certain point - a point that is usually only discernible retrospectively - cultures shunt off into the sidings, cease to renew themselves, ossify into Trad. They don't die, they become undead, surviving on old energy, kept moving, like Baudrillard's deceased cyclist, only by the weight of inertia. Cultures have vibrancy, piquancy only for a while. Lyric poetry, the novel, opera, jazz had their Time; there is no question of these cultures dying, they survive, but with their will-to-power diminished, their capacity to define a Time lost. No longer historic or existential, they become historical and aesthetic - lifestyle options not ways of life.

We are lulled into the belief that Pop should be immune to this process by the illusion to which those within any culture, any civilization, fall prey (perhaps it is is a necessary illusion?): the belief that our own culture will continue forever. The question we need to ask, then, is not so much 'will pop die?' but has pop already reached the point of undeath? Has it seduced us into an entropy tango, clasping us with zombie fingers as it slowly winds down towards permanent irrelevance? Questions worth raising, if only because as soon as they are no longer raised we can be sure that Pop really has reached its terminal phase.

What alarms me is the lack of alarm about Pop's current situation. Where is the chorus of disapproval and disquiet about a group like the Arctic Monkeys? Granted, it is not that the Arctic Monkeys are significantly worse than any of their retro forebears (although if anything ought to set alarm bells ringing, it is a situation where 'not being worse' than mediocre predecessors is thought of as worthy of comment, still less of muted celebration). What is novel is the discrepancy between the AMs' modest 'achievements' and the scale of their success. Critical success is more easily bought than ever, of course, so we shouldn't be surprised that the NME rates the Monkeys' album as fifth best British album of all time (disgust would be more a appropriate response actually). But such subjective and professionally expedient over-valuations would be insignificant were it not for the quantitative scale of the Arctic Monkeys' success - fastest selling UK debut album ever! What this implies is a libidinal deficit in Pop's audience as well as in its Old Media commentariat - a much more worrying trend.

The Arctic Monkeys' success is as glum news for Popists as it is for those of us who still pledge alliegance to Pop's modernist tendencies. (It should be noted here that, with r and b and hip hop faltering and stuttering, Popist-approved Pop has been one of the last remaining places where modernism's guttering flame persists.) As Marcello has suggested recently over at Church of Me, the new New Pop (Rachel Stevens, Girls Aloud) is barely secure, certainly not thriving, and its (relatively) disappointing sales compare ominously with the voracious triumph of Retro-Indie and the New Authenticity (Blunt! Jack Johnson!) There has been a kind of reversal, with new New Pop occupying the old pre-Indie independent position of the popular-experimental, and Indie dominating the mainstream. (Hence I would argue that, contra Simon in the Frieze article, it is new New Pop, not some putative, ghastly fusion 'of Grime and Indie rock', that is today's closest equivalent to postpunk.) A little insight into the times can be gleaned from the fact that NME has been reduced to ostentatiously banning Blunt from its awards ceremony (because there are a MILLION miles between his maudlin mumbling and that of their darlings, naturally). James Blunt versus Coldplay: is this what Pop antagonism is reduced to? A pseudo-conflict that should excite only Swiftian ridicule.

Hate's not your enemy, love's your enemy

Such plastic antagonisms (and NME/ Corporate Indie can't survive without convincing its consumers that they are an alternative to something, that there is some region of commonsense, complacent, middle of the road mediocrity that they don't already occupy) substitute for the real antagonisms that once sustained Pop. Even the most ardent devotees must sense something is missing - there's just a hint in Doherty's puppy dog junky eyes that even he recognizes the sad fact that even if he dies, it won't stop being Pantomime. (Although one suspects that the current malaise can in large part be accounted for by the fact that 'what is missing' is not even noticed, still less mourned or hankered for.)

Indie may have all but driven black musics out of the British charts, hybridity may be off the agenda, but you can bet your bottom dollar that all of those Indie bands just love hip hop and r and b. Pop at its most febrile was stoked by critical and negative energies that are now exhausted - or which have been exiled as far too impolite for today's pot-pourri, pomo buffet in which you can have a bit of Indie here, a bit of r and b there, where contradictions and anomalies have been photoshopped out, where it all happily fits into one well-adjusted consumer basket. If the revolutionary tumult of the postpunk era was characterized by restless dissatisfaction, anxiety, uncertainty, rage, harshness, unfairness - that is, by an atmosphere of relentless criticism - today's Pop scene is suffused with laxness, bland acceptance, quiescent hedonism, luxuriant self-satisfaction (ALL those awards shows!) - that is by, PR.

|  |

What Pop lacks now is the capacity for nihilation, for producing new potentials through the negation of what already exists. One example, of many possible. Both the Birthday Party and New Pop nihilated one another: far from existing in a relation of mutual acceptance or of mutual ignorance each defined themselves in large part by not being the other. One shouldn't rush to conceive of this in simple-minded dialectical terms as thesis-antithesis, since the relationships are not only oppositional - there is always more than one way to nihilate, and it is always possible for any individual thing to nihilate more than one Other. It seems at least plausible to suggest that the capacity for renewed nihilation is what has driven Pop. So let's dare to conceive of Pop not as an archipelago of neighbouring but unconflicting options, not as a sequence of happy hybridities or pallid incommensurabilities, but as a spiral of nihilating vortices. Such a model of Pop is utterly foreign to postmodern orthodoxies. But Pop is either modernist or it is nothing at all.

Just because something is current doesn't mean it is new. Saying that Pop was better twenty-five years ago is NOT to be nostalgic; on the contrary, it is to resist the ambient, airtight, total nostalgia that can not only tolerate but delight in the latest regurgitations on the Indie retreadmill.

Let's dispense once and for all with Popist-Deleuzianism/Deleuzian Popism's obligatory positivity. The fact we happen to be alive now doesn't mean that we must be committed to the belief that this is the best time to live EVER. We have no duty to search out entertainment and spread a little excitement everywhere we go. (Think of how hard to please audiences were in the mid seventies, in the midst of a veritable cornucopia by comparison with today's grim desert; and think of what that dissatisfaction produced.) So, please, no consumerist homilies about the fact that 'it is always possible to find good records, no matter what the year.' Yes, of course it is, but as soon as Pop is reduced to good records it really is all over. When Pop can no longer muster a nihilation of the World, a nihilation of the Possible, then it will only be the ghosts that are worthy of our time.

January 29, 2006

Fragments of a conversation with Julian House

I met Ghost Box's Julian House at the V and A last week, where, as part of the museum's February Friday Late event, he was part responsible for a display and demonstration by the 'Department of Pscyhological Navigation', a mock Government agency claiming to offer 'Creative Profiling and Unconscious Topography'. The DoPN was represented by a lovingly-produced booklet (recalling Observer books, Panini sticker albums, Ruritanian passports, Situationist pamphlets and, inevitably, HMSO information publications), a short film, and a number of official, even officious, personnel.

The booklet was executed with all the attention to detail we have come to expect from Ghost Box products. Its fonts, layout, and design were the typographical equivalent of Ghost Box sounds, conjuring another world (Britain of the sixties and seventies as imagined by Thomas Pynchon perhaps) where a socialist bureaucracy undertook a version of situationist psychogeography.

The booklet was full of activities, completion of which would supposedly yield a map of the participant's 'unconscious creative profile'. Participants were invited to read a series of evocative sentences (each one like the premise for an intriguing short story) before thinking of a number. The numbers were then to be plotted on a grid and the resultant 'mind plans' were to be matched to A roads. Participants were also invited to express emotions such as 'vague anger' or 'watchful jealousy' using a series of rubber stamps and to complete short 'stories' made solely out of images using a beautifully-prepared sheet of stickers ('remember,' the booklet warned, 'stories can be read on any axis and in any direction.') The results were then 'analysed' by an earnest-looking 1970s OU-lecturer-type in a suit who would portentously stamp the book with an apparently meaningful code.

The Department of Psychological Navigation seemed less like a transparent hoax than like a fictional organization that had forgotten it was fictional and stumbled out into what we are pleased to call the 'real world'. (Others were more credulous, seemingly happy to accept that the DoPN was fully authentic.) If Ghost Box LPs are like the incidental music for television programmes that have not yet been broadcast, or better, that have already been broadcast but in an alternative past, then the DoPN was like something that would have formed part of the fictional background in a television series, now detached from the series itself. Imagine UNIT without Dr Who. As with the Ghost Box tunes, you are invited to think: what context could this make sense in?

Some conversation topics

Julian and I agreed that one of the biggest problems with something like BBC1's Life on Mars is that has exactly the opposite emphasis: it is all foreground and no background. Life on Mars forces its 70s props into our face because behind then there is a fundamental emptiness. This is partly why, in Life on Mars nothing feels lived in.

British TV's problem, we agreed, is that is too in thrall to film. The classic serials of the seventies produced a world you felt a part of, a sense of inclusion to which 'wobbly sets' somehow contributed. The professionalism and glossiness of current TV, by contrast, locks you out, subordinates you to Spectacle. (I thought, later, of McLuhan's distinction between film - as a hot, spectacular medium - and TV - which he said was a 'cool', participative medium, whose picture literally has to be 'finished off' by the viewer.)

It occurs to me that Ghost Box is about a positive amateurism, where amateurism doesn't designate a failure to be professional so much as a deliberate deviation from how things are supposed to be done.

We discussed why Lovecraft is so singularly important. Lovecraft pioneered a fictional system or 'ritual literature' (Houllebecq) that was, by its nature, incomplete and participative. Incomplete, because each new contribution to the system, each new story, novel, character or creature, would produce new 'holes' which demanded to be filled (a process that is necessarily interminable), each component of the system, each collectable fragment, functions as a 'part-object' that can never be collated into a whole; and participative, because the system is genuinely a system, a collective product rather than the work of a single author. (It occurs to me, afterwards, that such 'participation' is the real alternative to the 'interpassivity' of so much digital culture.)

The notion of the derelict and the disused comes up. Julian raised the idea - via Gibson (in one of the later novels) - of disused cyberspace: the websites of companies that have ceased to trade, digital relics awaiting re-population.

__________________________________________________________________

More on hauntology - with even more promised - at Subject Barred.

January 26, 2006

Gothic Oedipus

'Gothic Oedipus', my Batman Begins piece, is now up at ImageText; it's a remix of what I wrote here so k-p readers shouldn't expect too many surprises.

The handshake you should worry about

... and one you really shouldn't, once you remember that it is the fellow pictured above who sold arms to the Hussein regime.

(Proving the point that, three years' on, this might be heavy-handed, but it's still relevant, and more lol funny than ever.)

January 23, 2006

Home is where the haunt is: The Shining's hauntology

1. The sound of hauntology

Conjecture: hauntology has an intrinsically sonic dimension.

The pun – hauntology, ontology - works in spoken French, after all. In terms of sound, hauntology is a question of hearing what is not here, the recorded voice, the voice no longer the guarantor of presence (Ian P: 'Where does the Singer's voice GO, when it is erased from the dub track?') Not phonocentrism but phonography, sound coming to occupy the dis-place of writing.

Nothing here but us recordings...

2. Ghosts of the Real

Derrida's neologism uncovers the space between Being and Nothingness.

The Shining - in both book and film versions, and here I suggest a side-stepping of the wearisome struggle between King fans and Kubrickians and propose treating the novel and the film as a labyrinth-rhizome, a set of interlocking correspondences and differences, a row of doors – is about what lurks, unquiet, in that space. Insofar as they continue to frighten us once we've left the cinema, the ghosts that dwell here are not supernatural. As with Vertigo, in The Shining it is only when the possibility of supernatural spooks has been laid to rest that we can confront the Real ghosts.... or the ghosts of the Real.

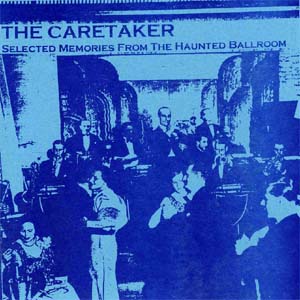

3. The haunted ballroom

Mark Sinker: 'ALL [Kubrick's] films are fantastically "listenable" (if you use this in sorta the same sense you use watchable)'

Where does

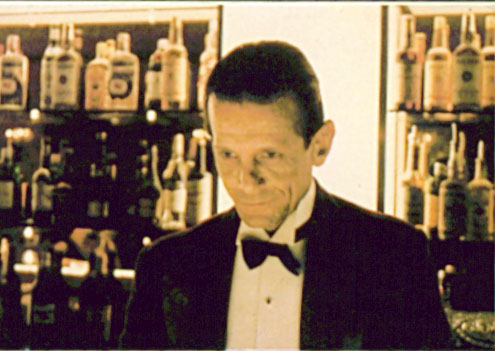

The conceit of The Caretaker's Memories from the Haunted Ballroom has the simplicity of genius: a whole album's worth of songs that you might have heard playing in the Gold Room in The Shining's Overlook Hotel. Memories from the Haunted Ballroom is a series of soft-focus delirial-oneiric versions of Twenties and Thirties tearoom pop tunes, the original numbers drenched in so much reverb that they have dissolved into a suggestive audio-fog, the songs all the more evocative now that they have been reduced to hints of themselves. Thus Al Bowlly's 'It's All Forgotten Now', for instance, one of the tracks actually used by Kubrick on The Shining soundtrack, is slurred down, faded in and out, as if it is being heard in the ethereal wireless of the dreaming mind or played on the winding-down gramophone of memory. As I.P. wrote of dub: 'It makes of the Voice not a self-possession but a dispossession - a "re" possession by the studio, detoured through the hidden circuits of the recording console.'

the singer's voice

GO?

4. In the Gold Room

Jameson: 'it is by the twenties that the hero is haunted and possessed...'

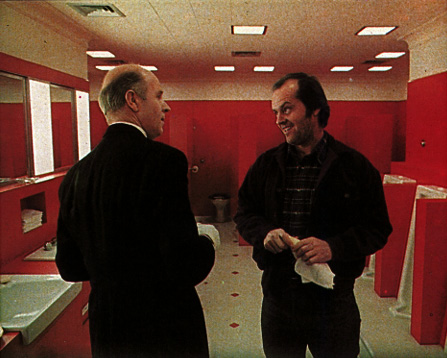

Kubrick's editing of the film does not allow any of the polyvalencies of that phrase, 'It's All Forgotten Now', to go un(re)marked. The uncanniness of the song, today and twenty-five years ago when the film was released, arises from the (false but unavoidable) impression that it is commenting on itself and its period, as if were an example of the way in which that era of beautiful and damned decadence and Gatsby glamour were painfully, delightfully aware of its own butterfly's wing evanescence and fragility. Simultaneously, the song's place in the film – it plays in the background as a bewildered Jack speaks to Grady in the bathroom about the fact that Grady has killed himself after brutally murdering his children – indicates that what is forgotten may also be preserved: through the mechanism of repression.

I don't have any recollection of that at all.

Why does this Gold Room Pop, all those moonlight serenades and summer romances, have such power? The Caretaker's spectralized versions of those lost tunes only intensifies something that Kubrick, like Dennis Potter, had identified in the pop of the Twenties and Thirties. I've tried to write before about the peculiar aching quality of these songs that are melancholy even at their most ostensibly joyful, forever condemned to stand in for states that they can evoke but never instantiate.

For Fredric Jameson, the Gold Room revels bespeak a nostalgia for 'the last moment in which a genuine American leisure class led an aggressive and ostentatious public existence, in which an American ruling class projected a class-conscious and unapologetic image of itself and enjoyed its privileges without guilt, openly and armed with its emblems of top-hat and champagne glass, on the social stage in full view of the other classes'. But the significance of this genteel, conspicuous hedonism must be construed psychoanalytically as well as merely historically. The 'past' here is not an actual historical period so much as a fantasmatic past, a Time that can only ever be retrospectively – retrospectrally - posited. The 'haunted ballroom' functions in Jack's libidinal echonomy (to borrow a neologism from Irigaray) as the place of belonging in which, impossibly, the demands of both the paternal and the maternal superegos can be met, the honeyed, dreamy utopia where doing his duty would be equivalent to enjoying himself.... Thus, after his conversations with bartender Lloyd and waiter Grady (Jack's frustrations finding a blandly indulgent blank mirror sounding board in the former and a patrician, patriarchal voice in the latter), Jack comes to believe that he would be failing in his duty as a man and a father if he didn't succumb to his desire to kill his wife and child.

White man's burden, Lloyd.... white man's burden....

If the Gold Room seems to be a male space (it's no accident that the conversation with Grady takes place in the men's room), the place in which Jack - via male intermediaries, intercessors working on behalf of the hotel management, the house, the house that pays for his drinks - faces up to his 'man's burdens', it is also the space in which he can succumb to the injunction of the maternal super-ego: 'Enjoy'.

Michel Ciment: 'When Jack arrives at the Overlook, he describes this sensation of familiarity, of well-being ("It's very homey"), he would "like to stay here forever", he confesses even to having "never been this happy, or comfortable anywhere", refers to a sense of dèja vu and has the feeling that he has "been here before". "When someone dreams of a locality or a landscape," according to Freud, "and while dreaming thinks "I know this, I've been here before", one is authorized to interpret that place as substituting for the genital organs and the maternal body."'

5. Patriarchy/hauntology

Isn't Freud`s thesis – first advanced in Totem and Taboo and then repeated, with a difference, in Moses and Monotheism, simply this: patriarchy is a hauntology? The father – whether the the obscene Alpha Ape Pere-Jouissance of Totem and Taboo or the severe, forbidding patriarch of Moses and Monotheism - is inherently spectral. In both cases, the Father is murdered by his resentful children who want to re-take Eden and access total enjoyment. Their father's blood on their hands, the children discover, too late, that total enjoyment is not possible. Now stricken by guilt, they find that the dead Father survives – in the mortification of their own flesh, and in the introjected voice which demands its deadening.

6. A History of Violence

Ciment: 'The camera itself -- with its forward, lateral and reverse tracking shots ... following a rigorously geometric circuit -- adds further to the sense of implacable logic and an almost mathematical progression.'

Even before he enters the Overlook, Jack is fleeing his ghosts. And the horror, the absolute horror, is that he – haunter and the hunted - flees to the place where they are waiting. Such is The Shining's pitiless fatality (and the novel is if anything even more brutal in its diagramming of the network of cause-and-effect, the awful Necessity, the 'generalized determinism', of Jack's plight than the film).

Jack has a history of violence. (And as I have written before, The Shining in many ways doubles Cronenberg's film of that name from last year. More of that parallel below.) In both novel and film of The Shining, the Torrance family is haunted by the prospect that Jack will hurt Danny.... again. Jack has already snapped, drunkenly attacked Danny. An abberation, a miscalculation, 'a momentary loss of muscular coordination. A few extra foot-pounds of energy per second, per second': so Jack tries to convince Wendy, and Wendy tries to convince herself. The novel tells us more. How has it come to this, that a proud man, an educated man, like Jack, is reduced to sitting there, false, greasy grin plastered all over his face, sucking up everything that a smarmy corporate non-entity like Stuart Ulman serves up? Why, because he has been sacked from his teaching job for attacking a pupil, of course. That is why Jack's will accept, and be glad of, Ulman's menial job in Overlook.

The history of violence goes back even further. One of the things missing from the film but dealt with at some length in the novel is the account of Jack's relationship with his father. It's another version of patriarchy's occult history, now not so secret: abuse begetting abuse. Jack is to Danny as Jack was to his father. And Danny will be to his child....?

The violence has been passed on, like a virus. It's there inside Jack, like a photograph waiting to develop, a recording ready to be played.

Refrain, refrain...

7. Home is where the haunt is

The word 'haunt' and all the derivations thereof may be one of the closest English word to the German 'unheimlich', whose polysemic connotations and etymological echoes Freud so assiduously, and so famously, unraveled in his essay on 'The Uncanny'. Just as 'German usage allows the familiar (das Heimliche, the' homely') to switch to its opposite, the uncanny (das Unheimliche, the 'unhomely')' (Freud), so 'haunt' signifies both the dwelling-place, the domestic scene and that which invades or disturbs it. The OED lists one of the earliest meanings of the word 'haunt' as 'to provide with a home, house.'

Fittingly, then, the best interpretations of The Shining position it between melodrama and horror, much as Cronenberg's History of Violence is positioned between melodrama and the action film. In both cases, the worst Things, the real Horror, is already Inside.... (and what could be worse than that?)

You would never hurt Mommie or me, would ya?

8. The house always wins

What horrors does the big, looming house present? For the women of Horrodrama, it has threatened non-Being, either because the woman will be unable to differentiate herself from the domestic space or because - as in Rebecca (itself an echo of Jane Eyre) - she will be unable to take the place of a spectral-predecessor. Either way, she has no access to the proper name. Jack's curse, on the other hand, is that he is nothing but the carrier of the patronym, and everything he does always will have been the case.

I'm sorry to differ with you, sir. But you are the caretaker. You've always been the caretaker. I should know, sir. I've always been here.

9.I'm right behind you Danny

Metz: 'When Jack chases Danny into the maze with ax in hand and states, "I`m right behind you Danny", he is predicting Danny`s future as well as trying to scare the boy.'

Predicting Danny`s future Jack might be, but that is why he could equally well say 'I'm just ahead of you Danny...' Danny may physically have escaped Jack, but psychically....? The Shining leaves us with the awful suspicion that Danny may become (his) Daddy, that the damage has already been done (had already been done even before he was born), that the photograph has been taken, the recording made; all that is left is the moment of development, of playing back.

Unmask!

(And how does Danny escape from Jack? By walking backwards in his father's footsteps).

10. The No Time of trauma

Jack: Mr. Grady. You were the caretaker here. I recognize ya. I saw your picture in the newspapers. You, uh, chopped your wife and daughters up into little bits. And then you blew your brains out.

Grady: That's strange, sir. I don't have any recollection of that at all.

What is the time when Jack meets Grady?

It seems that the murder --- and suicide --- has already happened, Grady tells Jack that he had to correct his daughters. Yet --- not surprisingly --- Grady has no memory

Bowlly's 'It's All Forgotten Now' wafting in the background

of any such events.

'I don't have any recollection of that at all.'

(And you think, well, it's not the sort of thing that you'd forget, killing yourself and your children, is it? But of course, it's not the sort of thing that you could possibly remember. It is an exemplary case of that which must be repressed, the traumatic Real.)

Jack: Mr. Grady. You were the caretaker here.

Grady: I'm sorry to differ with you, sir. But you are the caretaker. You've always been the caretaker. I should know, sir. I've always been here.

11. Overlooked

Overlook:

To look over or at from a higher place.

To fail to notice or consider; miss.

January 17, 2006

Hauntology Now

'The ghost as a cipher of iteration is particularly suggestive. At the beginning of Specters of Marx, Derrida talks about the way in which the anticipated return of the ghost may be mobilized on behalf of a deconstruction of all historicisms that are grounded in a rigid sense of chronology. 'Haunting is historical, to be sure', he writes, 'but it is not dated, it is never docilely given a date in the chain of presents, day after day, according to the instituted order of the calendar .' The question of the revenant neatly encapsulates deconstructive concerns about the impossibility of conceptually solidifying the past. Ghosts arrive from the past and appear in the present. However, the ghost cannot be properly said to belong to the past, even if the apparition represents someone who has been dead for many centuries, for the simple reason that a ghost is clearly not the same thing as the person who shares its proper name. Does then the 'historical' person who is identified with the ghost properly belong to the present? Surely not, as the idea of a return from death fractures all traditional conceptions of temporality. The temporality to which the ghost is subject is therefore paradoxical, as at once they 'return' and make their apparitional debut. Derrida has been pleased to term this dual movement of return and inauguration a 'hauntology', a coinage that suggests a spectrally deferred non- origin within grounding metaphysical terms such as history and identity."

- Buse, P., & Scott, A., (ed's), Ghosts: Deconstruction, Psychoanalysis, History, London : Macmillan, 1999, cited on this wonderful hauntology site

Why hauntology now?

(Perhaps this site has always been about that particular strand of cybergothic. Consider, for instance, the following ghostly gallery [all images clickable hyperlinks]:

|

|

|  |

Consider also the fact that I almost called the site 'Ghosts of My Life', in homage not only to Japan, but to Rufige Kru, who sampled Sylvian and folded the Time of my life in upon itself.)

Yet hauntology is about more than this place. The ghosts are swarming at the moment. Hauntology has caught on. It's a zeitgeist.

Uncanny coincidences. My end of 2005 reflections - spectrally-inflected in part because of BBC Four's pre-Christmas ghost week, but abandoned because illness and lack of net access would have made them untimely in the wrong way - were to have concerned last year's hauntological continuum: Ghost Box and Ariel Pink. As it happened, Mike Powell got in ahead of me. In the midst of Mike's excellent post, there are some remarks which provide some hints as to why hauntology should be so Now :

'Ariel Pink's House Arrest (to be reissued later this month by Paw Tracks) is plucking the same strings. I think there are two roads you can take with him: one is that his sound is solely that of a degraded ideal; you can hear the song he meant to create in some Porcelain Heaven, but now it's too far gone to recognize, and you're left with the process of an aural crumble. The other approach - which I do think is a different concept - is that his sound is a mold, a footprint, a negative, a series of suggestions that function independent of the ideal (the thoughts I'm having with Hey Let Loose Your Love). I used to think Ariel's thing was about degradation, but after three records, I realize that the wavering otherworldliness is the starting point of his aesthetic, not the sum of his decay.'

If I might extrapolate from what Simon calls these 'comments on half-erased or never-quite-attained songform': perhaps Ariel Pink's appeal is that his sound musters the sonic equivalent of the 'corner of the retina' effect that the best ghost stories have famously achieved. To understand what this entails, we need to reverse, or at least nuance, the commonplace which has it that the ghost is at its most scary only when it can't fully be seen. To say this implies that the ghost could be made the positive object of apprehension. Yet spectres are unsettling because they are that which can not, by their very nature (or lack of nature), ever be fully seen; gaps in Being, they can only dwell at the periphery of the sensible, in glimmers, shimmers, suggestions. It is not accidental that the word 'haunting' often refers to that which inhabits* us but which we cannot ever grasp; we find 'haunting' precisely those Things which lurk at the back of our mind, on the tip of our tongue, just out of reach. 'Haunting refrains' we are compelled to simulate-reiterate are sonic objets a around which drives circulate.

To return to Mike's point, we can now begin to see why it is important to think of the 'negative' aspects of Ariel Pink's sound not as the covering over of porcelain-perfect pop in fuzz and scuzz, but positively, as the means by which an anamorphic sonic object is produced. The anamorph, remember, can only be seen when looking askance, out of the corner of the eye.

In this respect, Ariel Pink has much in common with Jessica Rylan, who should be added to the hauntology canon forthwith. After seeing Rylan live last year, I referred to 'the beguiling illusion of a sonic object that would be perfect if only you could hear it more clearly. Yet the 'perfection' is an effect (a special effect, you might say) of the blurring and distorting techniques themselves.' I made similar observations after seeing Ariel Pink live, writing of 'a deliberate fogging of the digitally hyper-clean, with the result that what you are hearing is as much doubt and speculation as anything else.'

Why hauntology now? Well, has there ever been a time when finding gaps in the seamless surfaces of 'reality' has ever felt more pressing? Excessive presence leaves no traces. Hauntology's absent present, meanwhile, is nothing but traces....

*Haunt is a perfectly uncanny word, since like 'unheimlich' it connotes both the familiar-domestic and its unhomely double. Haunt originally meant 'to provide with a home', and has also carried the sense of the 'habitual'.

January 16, 2006

January 14, 2006

'It turned every TV into a time machine'

Following from these three posts on the hauntological power of TV, here's Julian House in an email, last year:

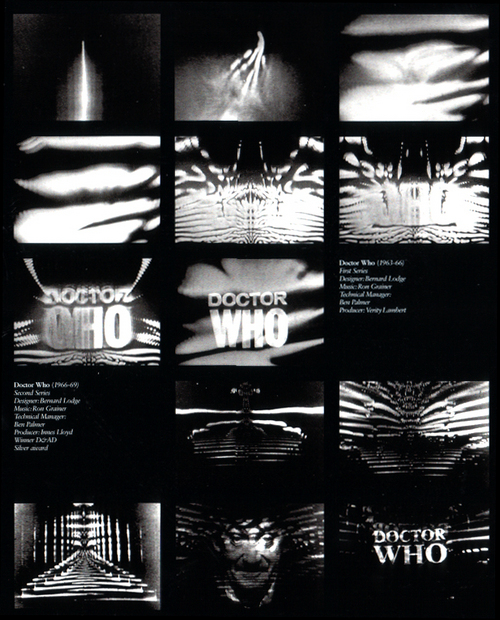

'In the same way that Derbyshire's theme was a landmark piece of British electronic music, Bernard Lodges' original titles did for British TV what Saul Bass's titles had done for cinema. The technique he used utilising TV feedback (or 'Howl-around' as it was called in the TV engineering world) was perfect for the program. It was organically beautiful, being based on a feedback loop it had associations with time travel, but most importantly it utilised the TV, the screen, the cathode ray tube for its effect. So it was absolutely about TV, the power of the TV itself - it turned every viewer's set into a time machine, the effect was to be drawn into the space of the program.'

(Titles for Out of the Unknown, also by Bernard Lodge)

January 12, 2006

The politics of TVerite

|  |

However misguided, self-serving and craven Galloway may be (and who, least of all George himself, really knows why he went in?), his critics are worse.

The attack on Galloway for 'abandoning his duties' is predicated on the pretence that what most MPs do most of the time is worthwhile and essential, as if they all spend all week crusading on behalf of constituents' leaky council house roofs, as if their role never involves anything so shameful, demeaning and ethically bankrupt as SEEKING PUBLICITY, as if carousing with alcohol-pickled hacks or parading around re-enacting 'Is This the Way to Amarillo' with Andrew Neil possesses infinitely more gravitas than appearing on Celebrity Big Brother. If there is anyone who believes that (now come on, there just might be someone... somewhere...), they should do themselves a favour by switching to BBC2 after the CBB show on Monday and watching Armando Iannucci's The Thick of It. From reality TV to TVerite... Next time you hear a New Labour lickspittle wringing their hands and tut-tutting about GG, think of hapless Hugh Abbot, BlackBerry-Whipped, spun right round like a record, his constituents only figuring in the fevered calculations of his Machiavellian rat-mind when there is some media capital to be gleaned from their plight...

One other question... why is 'raising awareness' via media-whoring not only acceptable but positively NOBLE if it involves hoary old rawk n roll Spectacle rather than Warholly 'hanging about with transvestites and models'? Which is to say: what merit do Snow Patrol and Cocaine Robbie possess which the CBB inmates lack? (UPDATE: Here is Ed Balls this very minute on Question Time saying that it was Make Poverty History, not BB, that 'involved young people in politics' last year.)

After all, maybe Mark S is right (see Jan 8 entry on tee-hee Society of the Respectacle [no permalinks]) and '“the spectacle” -- in its stratifed diversity ever more emptied, if not of implicit and/or unstated and/or immanent politix, then certainly of cap-letter left political activity THANKS LARGELY TO PRO-SITU SNEERING (and LAZINESS) -- remains therefore wide wide open for re-invasion'. Such a WAR ON POP - not a war against Pop but a war on Pop's territory would be the very opposite of populism, since it would stretch and pull Pop beyond its limits (rather than politely accomodating itself to a patronisingly (p)represented version of them). In the end, Galloway's gambit seems to be less populist than entryist - the populist underestimates the intelligence and capacities of the populace, whereas Galloway's 'error', according to his detractors, seems to consist in over-estimating 'what is possible' on a mass media vehicle like CBB.

One sad side-effect of Galloway's entrance into the Big Brother house has been the opportunity it has given New Labour to once again rhetorically re-fight the Bethnal Green and Bow election. (How many more times?) The N L position on Galloway's defeat of their candiate is as patronising as it is desperate: if only those poor, hoodwinked Muslims knew what they were letting themselves in for seems to be the latest version of the plaint. In a double-page, fully serious analysis of the Galloway-BB phenomenon that in no way, in NO WAY, traded on ghastly publicity-seeking kneejerk-meeja froth, The Independent, to its shame, followed its own denunciation of Galloway by allowing New Labour Hugh Abbot-a-like Denis McShane (or whichever Malcolm Tucker-type was ventriloquizing him) to write a painfully embarrassing score-settling paean to the 'hard-working brilliance of the Jewish-African-American, Oona King.' That's right... read that again... 'hard working.... brilliant.... Oona King'. (I did idly wonder whether the CBB producers might send King in, to play this year's Jacquie Stallone to Galloway's Brigitte Nielsen. But after seeing Oona's pig-thick, painfully slow-witted performances on More4's The Last Word a few weeks ago, it's clear that she's no Jacquie S.)

Most deplorable of all is the fusty piety-by-proxy in which the Bliarites indulge. Just as the US contracts out torture, so NL monkeys contract out their sanctimonious outrage to 'Muslims' whose views they do not, of course, share but which they must, being noble sorts, (unlike lazy, self-seeking GG) represent. No hack or NL pager-puppet will themselves dream of sneering down their nose at cross-dressers, Paris Hilton lookalikes and glamour models (being men and women of the people, like), so it's convenient that there's a Muslim (big) Other on hand to do it for them. I mean, what will the Muslims think about George spending time with people of such dubious morals? 'Muslim outrage' can both be expressed and disavowed at the same time... perfect...

Speaking of double standards, the strapline for the Times CBB blog ('we watch, so you don't have to') is revealing by what it attempts to disavow. Isn't the reverse the case? 'You read this, so we can watch' or 'we write this, so you don't have to feel ashamed about watching any more' would be closer to the mark.

Incidentally, the comments on this post suggest that the Galloway monstering isn't quite going to plan.

David graces us with his presence...

... and explains what it's all been about:

'For quite a while now some of the best bloggers have imitated us columnists.'

January 10, 2006

There's no decay, only renewal

Philip has a different angle on the bland britannia/ backwater England theme (also taken up by Ian here). Must say, my experiences chime more with Philip's than Martin's, especially the 'caught between the stasis of rurality and the churn of the city' bit.

The past is an alien planet

Why do stories of time travel into the past have so much more of an uncanny lure than those about time travel into the future?

Partly it is because they correspond with a fantasy that the past has never really, finally gone; time that seemed to be lost can, in fact, be regained. The idea that the past is a foreign country, that it is (only) a different place implies that it is still there, a parallel reality waiting for us to step (back) into.

The Bergsonian evanescence of Time, its aleatory senselessness, its radical unrepeatability, is a Horror we - creatures of repetition - can no more accept than we can accept the reality of our own deaths, in part because to accept that Time was irreversible, that it could not be re-iterated except ritualistically or psychoanalytically, would be to accept Death, our own and that of other people. If the death of others is bearable it is not only because we believe that they have survived, but because we have not given up, cannot give up, the thought that somehow, somewhere the time we spent with them remains available to be lived through again. Thus the prospect of time travel into the past is reassuring for similiar reasons that ghost stories are (remember Kubrick's observation that ghost stories are comforting because they imply that death is not the end). Ghost stories suggest, yes, a form of survival after physical death but more than that, the persistence of the past, its ineradicability - precisely the notion that time travel narratives are predicated upon.

To say that these reflections were prompted by BBC 1's new SF drama Life on Mars (the first episode of which was shown earlier tonight) would be to give the series more credit than it deserves. Yet, perfunctory and predictable as it so far largely is, Life on Mars is symptomatic enough to be interesting. Symptomatic of what? Well, of a culture that has lost confidence not just that the future will be good, but that any sort of future is possible. And also: Life on Mars suggests that one of the chief resources of recent British culture - the past - is reaching the point of exhaustion.

The scenario is that Sam Tyler, a detective from 2006, is hit by a car and finds himself back in 1973. (Almost a direct reversal of Michael Barrymore's situation in Celebrity Big Brother: he is like a man from 1983 who has inexplicably fetched up in 2006. Is it really only two years since he left the UK? I mean, impressions of Bernie Winters and Worzel Gummidge???)

The game that you can't help playing as you watch is: how convincing is the simulation of 1973? You're constantly on the look out for period anachronisms (so that, when I switched channel and began watching another, 2006-set programme, I kept thinking: 'Did they have THOSE in 1973?') The answer is that it isn't very convincing. But not because of anachronisms. The problem is that this is a 73 that doesn't feel lived in. The actual post-psychedelic, quasi-Eastern Bloc seediness of the 70s is unretrievable; kitsch wallpaper and bell bottoms are transformed instantly into Style quotations the moment the camera falls upon them.

(There must be some technical reason - maybe it's the film stock they use - that accounts for why British TV is no longer capable of rendering any sense of a lived-in world. No matter what is filmed, everything always looks as if it has been thickly, slickly painted in gloss, like it's all a corporate video. That remains my problem with the new Dr Who as it happens: the contemporary British scenes look like a theme park, a very stagey stage-set, too well lit.)

(And you think: can 1973 REALLY be THIRTY THREE YEARS ago..)

And it's all too (ha!) ICONIC ... 'Look Out There's a Thief About' public information films on black and white TV, Open University lecturers with preposterous moustaches and voluminous collars, the test card... The thing with icons, after all, is that they evoke nothing. (Presumably such nullity was what fascinated Andy Warhol about them, these white hole vortices which have escaped space and time, that suck fantasies into themselves but which give out nothing.) The icon is the very opposite of the Madeleine, Chris Marker's name - rhyming Hitchcock and Proust - for those totemic triggers that suddenly abduct you into the past. The point being that the Madeleine can only manage this time-snatching function because it has avoided museumification and memorialization, stayed out of the photographs, been forgotten in a corner. As I've pointed out before, hearing T-Rex now doesn't remind you of 73, it reminds you of nostalgia progs about 1973.

And isn't part of OUR problem that every cultural object from 1963 on has been so thoroughly, forensically, mulled over that nothing can any longer transport us back? (A problem of digital memory: Baudrillard observes somewhere that computers don't really remember because they lack the ability to forget.)

January 08, 2006

To the centre of the city...

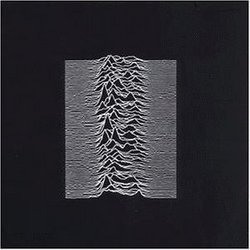

|  |

'You could feel something lurking in Luton, in the concrete, the brickwork, under the bridges, in the parks. It wasn't supernatural, it wasn't anything that would jump out of the dark pockets and grab you. It was more subtle, like the gradual onset of Alzheimer's. The muggings, race hatred, beatings, car crashes, suicides were just symptoms. Nobody wanted to be around when the disease suddenly accelerated and marched right over our heads–'

Brilliant post by Martin Beyond the Implode, ostensibly about listening to Joy Division in Luton. It tells you more about Unknown Pleasures than a thousand marks-out-of-ten, listen-to-the-nimble-basslines review could ever hope to; and more about what it is like to live in smalltown England than any Granta-type Eng Lit. essay. Here it is, the existential geography of Joy Division, those between-child-and-adulthood interzones and sub-urban shadowplaces seen from behind the windscreen of a car going nowhere, forever.

'You know you're in a fucked area when the KFC imitators loom large - Dallas Fried Chicken, where you can't differentiate between backside and beak, never mind between Halal, Kosher or Carcinogenic. So, we used to drive around all night. Hockwell Ring, Marsh Farm, Bury Park, Lewsey Farm, Wardown Park, Stopsley. And then sometimes out into the backwater villages, looking for signs of life.'

Where do you find this England? Hardly ever in films (you have to think back long ago, long before cinema lost contact with an England that wasn't either Gangsta Sexy or Notting Hill prim, to something like Sidney Lumet's The Offence for anything that summoned this sodium-lit hell); rarely in novels (even Ballard is in some ways too poetic; David Peace captures it better, not so much in physical descriptions, but in the pinched dialogue and claustrophobic, alcohol-fugged thought patterns of characters-as-environment). But it was everywhere in postpunk (not surprising that postpunk is a massive influence on Peace), in every note of Cabaret Voltaire, The Fall, PiL, Magazine, TG, Foxx's Ultravox, Tubeway Army, the Banshees, Alternative TV. (Part of the reason that postpunk pasticheurs like Franz Ferdinand and The Editors will only ever produce tracings that leave no trace is that they confront only the stylings and the forms, not the mushroom clouds and the piss-stenching alleyways that gave rise to those styles and forms.) In mourning and mocking the Trad Britannia of Empire and tea dance, of music hall and lazy Sunday afternoons, British Pop of the Sixties was still in thrall to Pathe nostalgia; postpunk saw through all that, looked headlong at the Concrete Island, 'the brickwork illuminated by 1,000 watt tungsten, the crowbar scuff marks across the doors of the ground and first floor flats, the intersections where the concrete turned to pungent yellow grass and the signs pointed'....

What is most draining about this landscape is its banality (decline can have poetry and magnificence; but retail parks and burger parades of the average cloned British high street are like garish grey stains, repelling all attempts at sublimation). And, as Lyotard observed in Libidinal Economy - 'they loved their annoymous pubs' - there is something willed about that banality, as if these jaded vistas expressed the replicant desires, the electric dreams, of the first country to host Kapital.

January 06, 2006

Feeling Brown

Can I echo I.T.'s recommendation from a while back for Mischa Benoit-Lavelle's weblog, Brown Feeling? It's shaping up really well, with posts on Karatani, Badiou, Zizek ...

When I asked him why it's called Brown Feeling, he wrote 'Brown doesn't have any opposite in the color-wheel, and it's the color of feces so its always strucken me as sort of abject and funny. And then with that in mind I tried to imagine being in a brown kind of mood and it just seemed kind of ambiguous and gross.'

Next phase of Trotskyist Populist insurrection....

'It's an unavoidable stage on the road to revolution,' Galloway announced...

January 05, 2006

Excremental Syrup: Paul McCarthy's USA

Fitting that Paul McCarthy’s La La Land: A Parody Paradise should have been showing in London in November and December, since the show is perfect for pantomime season.

It is literally excessive, in that there is too much to see and hear. The sculptures and outsize storyboard sketches on display in the Whitechapel gallery space turn out to be merely preparatory background for the infernal theme park-style installation, Caribbean Pirates, which McCarthy and his collaborators assembled in a crumbling warehouse just off Brick Lane.

There's an after-the-orgy/ post-traumatic mood in the chilly warehouse space, appropriately, since part of what the show examines is the reversibility of the orgiastic and the traumatic. Enter the space and you're confronted by ships, hulls, cabins and decks, including 'a splintery houseboat that might have drifted here from Cape Fear', each of them splattered with the detritus of atrocity and pleasure. As the Whitechapel material - some of which is retrospective and archival - establishes, Carribean Pirates is a kind of summation and recapitulation of McCarthy's signature obsessions. All of McCarthy's incarnations - Vienna Aktionist-inspired performance artist; painter of obscene doodles; sculptor of penile and scrotal grotesqueries - find expression in the show. The second-rate continually re-invent themselves; the great can only repeat themselves, differently, and McCarthy's work has all the compulsive repetitiveness of a trauma victim. The trauma his work registers is at one level the same one hidden and revealed in the sickly sweet Love and Napalm day-glo goo-goo dream-nightmare of Amerikan popular culture, a repellent-fascinating collage chopped together from pantomime, penises and porn.

McCarthy and his supporting crew of technicians and actors filmed a month's worth of now nauseating, now queasily hilarious performances, in which leering rubber-penile-nosed pirates re-enacted scenes of plunder from history and myth. The resulting films were then projected, in a vertiginous, quasi-haphazard manner, onto the walls of the warehouse, their time-sequences delirially cut and part-reserved, their soundtracks clashing; words are all but indistinguishable, drowned out by screeches and yelps of ecstasy, terror and pain issuing from the throats of those who might be the damned or the saved, or both. Bosch meets Bosch as limbs are brutally severed with screaming power tools. It is impossible to totalize or adequately narrativize the experience of walking through the space. The show, a reliquary of fragments, an assemblage of part objects, repudiates wholeness and the wholesome.

The buccanner bacchanalia la-la-land is less a Mutiny in Heaven than a Mutiny INTO heaven, a freebooters' taboo-breaching gatecrashing of Eden taking the form of a total refusal of the reality principle, an attempted recovery of the Imaginary, uncoded, radically innocent infant body. The storyboard sketches on display at the Whitechapel obsessively repeat variations of the phrase, 'cut the penis', indicating that the cost of entry into La La Land is the removal of the male organ. Yet the penises that erupt everywhere from the faces of the pirates are an embodiment of the inevitable frustration that awaits any attempt to regain a Paradise that can only ever be experienced as lost.

The transgressive drive to overcome the coding of the body was evident in McCarthy's early work in which he literally wallowed in such bodily excreta as saliva and shit. Films of those performances confront the viewer with their own internal censor, the involuntary and autonomic disgust reflexes at work in the skin and the gut which are the superego in person. The performances seem to be no less than attempts to reverse primary socialization, where the body is divided from the outside and then internally zoned into clean and unclean areas. The treatment of shit – what was once inside the body now abjected into an object of disgust located outside the body – is of course especially crucial in this process , so much so that Lacan famously claimed that human beings differentiated themselves from animals only at the point when they had a problem dealing with their own excrement.

In Caribbean Pirates, blood and shit become ketchup and syrup, a reverse trans-substantiation, an act of debasing sacralization, in which the vital fluids of Amerika's obscene-obese body-politic are desublimated from their advertising-generated Ideal into filthy physicality. Bodies are drenched in Hershey and Heinz; tin after tin of chocolate syrup is poured into ravenous mouths through plastic funnels which act as artificial, externalized sphincters. This vision of excremental syrup as a kind of sickly-sweetened diarrhea, a redeeming delirial elixir that passes through the body unchanged, that can be re-consumed even as it is expelled, has much to tell us about the fantasmatic economy that underlies America's financial economy.

Carribean Pirates is McCarthy's take on the Disneyworld ride, Pirates of the Carribean, the inspiration for the recent Johnny Depp film of the same name. The obvious question it prompts - who are the real carribean pirates? - has an equally obvious answer. How can they not be the agents of the Outlaw Superpower founded on slave-trading and plunder?

McCarthy's obsession with pirates can be seen as part of a general exploration of the concept of the Outlaw, so intrinsic to American mythology. (Some of his other work has dealt with the theme of the West.) The ineluctable conclusion to which Caribbean Pirates tends - that it is not the Law but the Outlaw that is tyrannical and terrorising - contradicts the implicit transgressive-utopianism of McCarthy's early performances. Unlike Burroughs, an obvious comparison, McCarthy seems to see the pirate not as a Utopian outsider, but as the Real face of mainstream American culture.

What McCarthy does have in common with Burroughs an awareness of the inherent theatricality of Sadism. In Burroughs’ novels, cruelty never occurs without stage-sets, costumes and mummery. To be humiliated is always to be ritually humiliated, as we can scarcely fail to be aware in the era of Abu Ghraib; and it’s impossible to walk through the seasick-scapes of La-La-Land without being reminded of Abu Ghraib. Simultaneously, however, we must recall that Abu Ghraib was already, in itself, a deranged piece of performance art. 'The very positions and costumes of the prisoners suggest a theatrical staging, a kind of tableau vivant, which brings to mind American performance art, “theatre of cruelty,” the photos of Mapplethorpe or the unnerving scenes in David Lynch’s films.'

This might be 'the obscene underside of American culture' but it is very far from being ‘the obscene underside of the Law’, since in a culture in which Law has been replaced by laissez-faire hedonic liberalism, Law and ritual survive only in their parodied-obscene forms. The ritual that has been disavowed at the level of the official culture, erupts at the level of the political unconscious.

January 02, 2006

Now wait for last year, again, or: how King Kong wiped my memory

What's the point in the first hour of King Kong?

Some may ask - and not without good reason - what's the point in all three hours, but the sense of gratuitousness is at its most pressing in the opening part of the film. The ostensible answer - to 'establish' the characters so that there is someone for us to 'identify' with in the action sequences - is plainly unconvincing for the simple reason that the characters are pasteboard thin, no more filled out than their counterparts in the 1933 original. Jackson is not interested in characters, and what interest we viewers have in the film has little to do with characters either.

I suspect the real answer lies in the strange, necrophiliac impulse that presumably drove Jackson to remake the picture in the first place. That impulse leads to a cinema of the past that is no longer a cinema of History; a cinema of FX that leaves no traces.

In his classic analysis, Jameson identified a waning of the historical sense as a defining characteristic of the postmodern. The 'nostalgia mode' is evident, not so much in films whose content is backward-looking, but whose form belongs to the past. Thus an archetypal postmodern film such as Body Heat will be characterised by a tension between its contemporary setting (the 1980s) and its Noir form (which derives from the 30s/40s). The 1976 Kong remake, directed by John Guillermin at a time in which remakes were not so wearisomely ten-a-penny as they are today, corresponds to this model much more than does Jackson's film. Neither the contemporary setting nor a post-Oil crisis plot involving a petroleum expedition can disguise the fact that the 76 version (undistinguished and rather boring as it was) runs on a 30s Adventure movie template.

Someone else's memories...

Jackson's film is something different again. It eliminates the tension between contemporaneity (setting) and the past (form as revenant) by ignoring the present altogether and setting the film in the year the original film was released, 1933. The result is a peculiar, slightly creepy, homage, which might well constitute a new type of postmodern arfifact altogether. The 21st century obtrudes into Jackson's King Kong only in the form of technology. The implicit conceit is that this is the film that would have been made in 1933 were the technological means available at that time. FX are, naturally, the real stars of Jackson's King Kong. (I need hardly point out that Jackson's whole career as a film-maker, from the ecstactic mondo trash of his early features through to Lord of the Rings, rests on a mastery of special effects.) In King Kong, FX have replaced history. Or rather, 'history' - now flattened out into a series of period signifiers - has itself become a kind of special effect. (Technology substitutes not only for history but for culture, too; in 2005, technological progress is the only faith that remains to us.) Even if the simulation were note-perfect accurate, History, in the Marxist sense of struggle, antagonism and contingency, would still be photoshopped out. The Depression is a stage-set, an inexplicable backdrop. This a museum without History, the Past as Experience, Theme Park...

I'm reminded of Wash-35 in Dick's Now Wait for Last Year, a 'painstakingly elaborate reconstruction' of Washington in 1935, built on Mars at the behest of a plutocrat who wants to walk through the city of his childhood again. 'Here was Grammage's, a shop at which Virgil had bought Tip Top comics and penny candy. Next to it Eric made out the People's Drugstore; the old man during his childhood had bought a cigarette lighter here once and chemicals for his Gilbert Number Five glassblowing and chemistry set. "What's the Uptown Theater showing this week?"'

Yet there's something touching about Wash-35 - according to Jameson it is one of 'Dick's most sublime inventions' - whereas watching the simulations of 30s New York in the first few minutes of King Kong - from the opening Al Jolson number through to the Vaudeville routines and scenes of the Depression-hit poor - makes for an empty, if eerie, experience. Perhaps it's because this is nostalgia for something that Jackson himself had never encountered, nostalgia for the context of a film he in any case would have only have seen decades after it had been released, that these scenes have a strange hollowness and depthlessness. It's a nostalgia that is already thoroughly mediated, a replicant nostalgia, a nostalgia for someone else's memories.

Someone else's dream

There's something homologous in the way that the film refuses to linger in the memory. Walking out of the cinema, I found myself unable to bring any images to mind. It felt like there was nothing to talk about, as if the film had instantly erased itself from the memory. No doubt that is because the most arresting sections of the film - the CGI action sequences - never enter visual memory at all. If the breakneck tactility of these sequences is retained, they are more likely to be stored in the body's motor reflexes than in its visual or narrative memory.

Is such an immediate auto-erasure inherent to CGI, or is it because so many CGI-dominated films are devoted to high-speed action that CGI films typically leave so few traces? As I try to recall King Kong now, it is like attempting to bring to mind a dream, but a dream I never really had myself, someone else's dream...

UPDATE:

1. Simon asks why did I bother seeing it at all? Partly what fascinated me was the discrepancy between the uniformly laudatory press the film has received here and the disdain expressed by I.T. and Savanorola after they saw it. Their view - that it was tedious, poorly edited and racist - bore no relation whatsoever to the standard media position that this was a well-made blockbuster. In addition, media hype is a kind of mind virus, a mental itch... and sometimes you have to scratch...

2. '[N]o one ever looked at a staggeringly mysterious sublime - but patchy - early Icon of some religious scene and said: Well, what's wrong with this is that it isn't REAL enough...' Penman takes up the cudgels. I think a Baudrillardian AND a psychoanalytic critique of digital realism can be derived from Ian's remarks here. It is important, though, to distinguish between the Real and the realistic, since this distinction is precisely what is lost in the pursuit of seamless CGI simulation. Nothing highlights the retreat of the Real under pressure from the realistic more than Kong. Here Baudrillard and Zizek would be in perfect harmony - realism imagines that the Real can be grasped head on, without residue or symbolic debt, whereas for them, it can never be apprehended directly, only anamorphically, out of the corner of the eye. The theatrical and the artificial, i.e. the very things collapsed in the name of realism, are therefore not properly opposed to the Real; they are the means by which the Real can be registered, the frames through which we can glean something of its contours. Kong is a film without the unconscious. It is as as odd, as pointless - and as autistically point-missing -, as if a particularly literal-minded individual had made a minutely observed, fastidiously reconstruction of someone else's dream. Everything is lost in translation.

Catherine takes up the line about technology being our last remaining faith.