November 29, 2010

Kettle logic

No left turn into Parliamentary Square, flashed a sign as we marched through Whitehall last Wednesday. But all the other signs are suggesting quite the opposite: there's a tentative but very definite shift to the left in the mainstream, nowhere better exemplified than by NUS President Aaron Porter's admission that he had been "spineless" in failing to support student militancy. This leftward lean by the NUS - which has long been a bastion of capitalist realist moderation - is a signficant symptomatic moment. See also Polly Toynbee's slight shift away from centrist condescension, as evidenced in the difference in tone and stance between these two pieces/5448/>IT).

Lenin and IT have written reports on the kettle, so I won't detain you for long by repeating what you've already heard. Suffice it to note that the mood walking down Whitehall from Trafalgar Square in the winter sun was almost jubilant: far from the negative solidarity you might have expected, cabbies and bus drivers honked their horns or waved in support of the young protesters. Even after the kettle was imposed, the mood remained remarkably good humoured in the main. You already know about the thin pretext for the kettle, the suspiciously abandoned police van, which was only attacked once the kettle was already in place. As others have observed, there can be no doubt that the real purpose of the kettle is to punish people for protesting, and to deter them from doing so in the future. Lenin is quite right: it's imperative that this doesn't happen - the ruling class are counting on the street militancy fizzling out as suddenly as it flared up. We have an opportunity here, not only to bring down the government - which is eminently achievable, (keep reminding yourself: this government is very weak indeed) - but of winning a decisive hegemonic struggle whose effects can last for years. The analogy that keeps suggesting itself to me is 1978 - but it is the coaltion, not the left, which is in the position of the Callaghan government. This is an administration at the end of something, not the beginning, bereft of ideas and energy, crossing its fingers and hoping that, by some miracle, the old world can be brought back to life before anyone has really noticed that it has collapsed.

At the moment, so many mainstream commentators and politicians resemble nothing so much as the denizens of the post-apocalyptic world of Richard Lester's The Bed Sitting Room (which, of course, I'm grateful to Evan for drawing my attention to): tragicomically persisting with the same customs and habits as if the catastrophe hasn't happened. Until the weekend, Aaron Porter was walking the ideological junkyard, apparently under the delusion that a career as a New Labour politician was still on the cards. But his change of position suggests that even opportunists have seen which way the wind is blowing. It looks as if the situation might be starting to dawn on Clegg, who increasingly has the cheated and desperate look of a man who has sold his soul to the devil at the very moment the devil went out of business.

Victory will require a range of strategies, and new kinds of intervention are being improvised all the time - see for instance the University For Strategic Optimism, video above. Victory will also require others to follow where the students have led - if public service workers join the militancy, then we can look forward to a Winter of Discontent every bit as bitter as the one in 1978.

In addition to the physical kettling of the protests, we're also seeing a media strategy of containment. Hold your nose and take a look at Jan Moir if you want to see a prize example of this kettle logic. The preferred strategy of the old guard seems to be one of phobic panic disguised as insouciant disdain: witness the way Moir shuttles between sexist and ageist belittling ("St Trinian's Riots", "fem-factions", "boys and girls", "throwing tantrums") and moral horror (the deploring of "violence and damage"). The protest, in other words, was both a trivial jape and breach of civil order so serious that it merited "detain[ing] thousands of the students for hours in a ‘kettling’ movement". I wonder, incidentally, how long the "civic-minded" Moir and her fellow Mail journos would "fight the urge" to "trash cop cars" if they were kettled; I fancy their patience would break long before that of the protesters did. (Imagine the mood hacks would be in after eight hours without alcohol.) Then of course we get the wheeling out of the capitalist realist canards ... "the cold reality of the economic times. There is no money left to fund further education for all. Which in any case is an extraordinary privilege, not a right."

In reply to which I can do no better than quote Third Class on a One Class Train's excellent post:

- The economic argument (and the alibi given by the Liberal Democrats to explain their about-face on the fees issue) is that we, as a nation, don’t have the money for things anymore. We certainly can't afford to pay tuition fees, and give grants rather than loans. We managed both of those things for several decades up to 1997, without the economy collapsing around our ears and people pushing wheelbarrows of money through the streets and/or queueing for bread and salt, but never mind.

Moir demands, with a perfectly straight face, that students "ask themselves why they should expect hard-pressed taxpayers to fork out for their further education, when a great number of those taxpayers are less well off than the students’ own families." Let's leave aside the little matter of the fact that this didn't seem to trouble Moir and her fellow right wingers when they were receiving free higher education; let's also leave aside the fact that the current government is full of millionaires who received the same "privilege". How, you have to wonder, can Moir expect that those same "hard-pressed taxpayers" take cuts in order to fund the bankers, who are more well off than almost everyone else?

Riding Third Class Train makes a crucial point about the way that the current capitalist realist discourse depends upon a ridiculously outdated figuration of The Student:

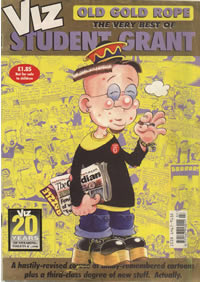

- There’s still a dimwitted lack of understanding of the nature of these actions - too many television and newspaper reporters seem to be operating under the assumption that those of the protesters who are currently students are only attempting to get their own fees waived. A moment’s consideration would of course reveal that these people will all be working and paying back their loans by the time the Browne proposals are in full effect. The inability to comprehend the idea that people can have motivations other than self-interest reveals far more about the Burleyesque sections of the media than it does about the marchers. The archetype of the spoiled, selfish student living it up on taxpayer money, never particularly fair, is now positively antiquated. Viz - often a reliable social barometer - dropped its 'Student Grant' character years ago, but it's being dug up and spat back at us in 2010. Desperate stuff.

To dismiss the students (as as every organ in the land seemed to do) as wanting ‘something for nothing’ or ‘everything handed to them on a plate’ is to completely, wilfully misunderstand the situation. The immediate demand of the protesters was for a proposed fee increase to be scrapped. In other words, for the maintenance of a situation in which students work jobs in term-time, live in cheaply built (but tastefully coloured!) PFI rabbit hutches, study hard, and three years later, accept a debt measured in the tens of thousands that will hang over them for most of their adult lives. Compassion for these students might be dulled by the thought that they will eventually be earning high salaries - the risible Gove defended the Browne Report with the uncannily bad argument “why should a postman subsidise someone who will go on to become a millionaire?” - but in times like these, how many students (even those in vocational subjects) do we really believe will be prospering after they graduate? It should be obvious that what these students want is something for something - the prospect of some kind of reward for all of the hard work and financial risk they‘ve undertaken.

IT has also pointed out the way in which the stereotype of the lazy student is completely out of touch with the reality of so much student experience today. No doubt the students in Moir's and Toynbee's families - who, I think we can assume, will be at elite institutions - have an experience of university life which differs little from that which Moir and Toynbee enjoyed. ("Rich parents for all," as one of the more acerbic placards had it last week.) But many students now routinely have to work long hours during term-time, meaning that they barely have the energy to read anything. By comparison with former generations, these students are paying more for a worse quality educational experience, not to mention the fact that their degrees will in many cases fail to yield them any significant long term financial advantage. I take Alex Callinicos's point about the dangers of 'generational' politics, but there is surely an unavoidable generational dimension to the current situaiton. Witness Paxman's patronising treatment of young protesters on Newsnight last week. Transformed from attack dog rentasneer into the kindly, avuncular advocate of capitalist realism, Paxman "explained" to the teenagers that, yes, it's unfair that he received an education completely gratis and that they will have to pay thirty grand, but sadly, that's just how things are - there's no money left. Generational affiliation here is a matter of political decision. I effectively belong to Paxman's generation in that I too received higher education completely free of charge. But the issue is question is whether one finds it conscionable to stand by while the young systematically denuded of the "privileges" that we took for granted. It's true that higher education has been massively expanded over the past thirty years, but that isn't the fault of the young. They are the victims of an ill-thought and poorly planned out experiment in the expansion of the sector which successive governments have pursued on the grounds that the UK would need more graduates in order to be internationally "competitive". It's not even as if the young have the alternatives to higher education that once existed. So here they are: the ConDemned, and it's down to us whether we stand with them or watch them get further sold out and abandoned.

Then there's the attempt to rubbish the motivation of the protesters: they were just along for a "laff", Pied-Piper lured along by our old friends, a hard core of anarchists. Even if we were to accept this, Moir and Gove need to explain why it is that these "anarchists" - who, presumably, didn't start scheming only a few weeks ago - have suddenly been able to motivate the young so effectively. Despite the best efforts of the media and the politicians to maintain business as usual, something has changed. But this change is precarious. We have to do everything we can to keep it going - supporting protests and occupations wherever we can, introducing and exacerbating antagonisms in the workplace, thinking and discussing new strategies, continuing to build a "new politics" that has nothing to do with the dead neoliberal consensus that the coaliton is seeking to resuscitate.

November 18, 2010

Fear and misery in neoliberal Britain

Don't worry, I haven't given up blogging - nor do I value blogging any less than I used to. The reason there have been no posts here for ages is the because the pressure of precarity has reached a new pitch of intensity. I'm teaching two undergraduate courses, an MA course and adult ed this term - at three different institutions. That plus a relentless round of public speaking means that I'm counting my time off in minutes at the moment. I don't even have time to invoice for money that I'm owed.

If you've emailed me and I haven't responded, please email again - it's just impossible for me to keep up at the moment so I welcome reminders.

Apropos the above, I present below something I wrote for this excellent event - one of a number of recent events at which I've spoken that have prompted all kinds of thoughts which I would have liked to have recorded here, if only there was time (a hundred virtual posts slowly dying as the unyielding pressure of precarity builds). What I'm pleased to report is that, at all the events I've spoken at recently, there is a growing feeling of militant optimism. We saw the first signficant displays of public anger at the student protests last week, and the mock-horrified response of the mainstream media to this mild "violence" shows how out of touch it - and parliamentary politics - is with the post-crash mood. Of course, they are not only out of touch - like the coalition government, they are working desperately hard to maintain the simulation of a business-friendly "centre ground", the conditions for which were vaporised by the 2008 crash.

The passage I've pasted below - the introduction to my presentation, which was entitled "We're not all in this together: public space and antagnonism in the wake of capitalist realism" - was intended to be a kind of minimally fictionalized phenomenological tuning-up exercise, to give a predominantly non-UK audience a sense of what it has been like to live in the UK under capitalist realism. Everything here is based on genuine experiences, although some experiences have been compressed and condensed, and the experiences are not necessarily mine.

- Now:

The swipe card doesn’t work. The machine senses anxiety, you’re sure of it. It knows the card is not yours. You try the card again. Nothing. Same red light. The card isn’t yours, but you should have access to the building. You had to borrow someone else’s card because it is only possible to get swipe cards between the hours of 9 and 1 and you are working at these times.

Someone is behind you. You feel uncomfortable. Will they notice that the card does not belong to you? You try the card again. Again nothing. Red light.

Your phone rings. You struggle to get it out of the bag. By the time you have it, the call has gone through to the answering service. You see that the call has come from another of your employers. A familiar anxiety grips you: what have you done wrong now? But you have no time to worry about that at the moment.

You try the swipe card again. At last, the green light comes on. You’re through the door.

Rushing down the corridor. Which floor were you supposed to be on? You rifle through your bag until you find the documentation. You should be on this floor, but at the other end of the corridor. You walk towards the room number. But suddenly your progress is blocked. There is a no entry sign: an office that cuts the corridor in half and through which there is no access.

It’s a nightmare topology. Every time you seem to get close, another obstacle appears. You will have to go out of the corridor, down the stairs and up to the next set of stairs, facing a number of swipe card-access doors on the way.

By now the five minutes you hoped to have before you start is evaporating rapidly.

By the time you reach the room you were heading for, you are already late. You log-on to the computer. Or you try to. The log-in is rejected. You try again. No luck. Then you remember: you’re trying a log-in from one of the other institutions that you work at. It’s difficult to keep track sometimes. You remember the correct log-in, quickly scan one of your email accounts. See an email from an administrator. Have you filled in your bank details form? Yes, you’ve filled it in, you think. Weeks ago. But of course you can’t be sure - maybe you only thought you had filled it in. Have they lost it? Flash of anxiety: will I not be paid this month? Last year, when you filled in all the same forms that you have to complete again this year, you were not paid for a whole fifty-hour contract, until you pointed out the mistake. Will the same thing happen again?

But there’s no time to worry about this now.

You have a room of seventy students waiting to be taught.

Such is life in the UK’s bloated and over funded public institutions.

Welcome to Liberty City. The busier you are, the less you see.

Ten years ago: the New-Path Institute

The psychiatrist asks you if your mood has improved.

You say no.

The psychiatrist says that the dose needs to be increased.

You don’t respond. You can’t. The drugs you’re taking and the condition you are suffering from give you the cottonhead response time of a zombie. The psychiatrist feels very far away, like you are seeing him through a fish-eye lens.

You don’t need to respond. It’s not about your responses.

Besides, there’s a sneering voice in your head constantly shouting at you.

Of course the drugs won’t work.

Of course you won’t get better.

Because there’s nothing wrong with you.

Just give up.

But that’s easier said than done.

The best you can hope for is a coma.

After the consultation, you return to your bed. Everything feeling very heavy, as if a crushing undersea pressure is bearing down on you. You lie on the bed, absolutely convinced that this is the truth - the raw unvarnished Real. Strangely, that remorseless glacial sense of certainty does not lessen your anxiety or bring you any relief. You cannot rest, even though you are catatonically immobile. Your heart is pounding. Jackhammer thud out of a Poe story. It gets faster and louder until the only thing louder is the voice in your head.

Later, you say to a nurse:

So that’s what the treatment amounts to? Drugging and incarceration.

They nod. In the background, someone is howling.

Now:

Rush away to one of the other places you work. You are supposed to photocopy some texts.

But by the time you arrive in the corridor, all the doors are locked. No-one there.

This is the second time this has happened. Last time the photocopier wasn’t working.

You should have come earlier today. But there wasn’t time then.

Defeated, but trying to ensure that the two-hour round trip is not a complete waste of time, you go to the library, using the temporary swipe card that you were given because your contract has not been prepared yet. You take some books off the shelf and try to check them out. No dice. Your library record has not yet been prepared.

Can you come back later?

Yes, you can come back later.

On the train home. Claustrophobia-inducing crush. You’re so anxious about having your iPod or your phone stolen that it would almost come as a relief if they were.

Exhausted, still standing up because there is no space to sit, you think about reading the book in your bag. But the temptation of the free paper is too great. Its headlines fix on your tired mind like predators that have eyed a stricken animal. The little oedipal-celebrity narratives hook you in. Everything collapsing into the universal form of the tabloid. Idle chatter subsuming all other news. Politics as a family soap opera. Nothing going on except ambition, intrigue, envy. You’re bored even as you are fascinated.

Six years ago:

In the office of the occupational therapist.

You are being asked to prove that you are mentally fit.

Because - as the Human Resources manager kindly pointed out - you have suffered from stress in the past. (The thought flashes through your mind - not that they cared when you were suffering.) But now people are concerned.

The anger that you’ve been showing towards management can only be a sign that you are unwell. A little unbalanced.

Don’t worry. No-one is attacking you. We’re all here to help.

You say to the occupational therapist:

If I say management is conspiring against me will that prove I am mad?

Now:

Stepping over the vomit, you remember too late: only a fool would go out into a provincial English town centre late in the evening. It’s night of the living dead out here.

Screams that sound like they come from the Dante-damned. And that’s just from the people who are enjoying themselves.

The lurching zombie threat of violence simmering.

Try not to catch anyone’s eye.

When you go by Accident and Emergency, you see all the walking wounded, and some who are not walking. All the casualties of the UK’s many happy hours.

You remember a doctor saying that twenty years ago, the night shift was so boring that the medics would engage in wheelchair races with one another. Not any more. Not with all the knives, gun crime, fights, alcohol-related accidents, stomach pumps…

And all the superbugs breeding in the wards….

You reach home, switch on the TV. Emollient patrician voices crying crocodile tears. Public services to be massively cut back. 30%, 40%.

A new age of austerity.

Aristocrats and millionaires telling us: we’ve all got to do our bit.

We’re all in this together.