November 20, 2008

Nannies with whips

- Surprise, surprise. How we all hate the nanny state - until nanny takes a day off. Then we want nannies galore. We want nannies with whips, nannies with locks, keys and public inquiries. Labour, Liberal or Tory nannies are suddenly the order of the day. The response to the case of 17-month-old Baby P has been a classic of incoherent social comment. The media, which normally excoriates every case of local authority meddling and red tape, has torn into Haringey council for failing to spot a dreadful case of child abuse.

Well, quite. This is the most puzzling aspect of the Baby P moral panic: right wing commentators calling for more state regulation. It's especially noteworthy since social workers' standard straw man role in right wing delirium is as do-gooding meddlers and child stealers, ready to break up families on the slightest of pretexts. This is proof, once again, of the essential libidinal function that public servants play in late capitalism: as figures to be blamed when things go wrong.

Of course, the Baby P story has emerged just as the Jonathan Ross/ Russell Brand scandal has faded; and the fact that it coincides with the John Sergeant furore shows how media-manufactured outrages produce strange equivalences (appalling child abuse, a telephone prank gone wrong and a beloved television presenter leaving a light entertainment TV show are implicitly deemed to be equally worthy objects of our excited patterns). As Charlie Brooker pointed out in his Screenwipe programme this week, newspapers, long since outdone by the web as deliverers of news, increasingly rely on campaigns to attract readers. But it's no accident, surely, that all three of these latest campaigns centrally feature public services.

November 11, 2008

Incapacity benefit

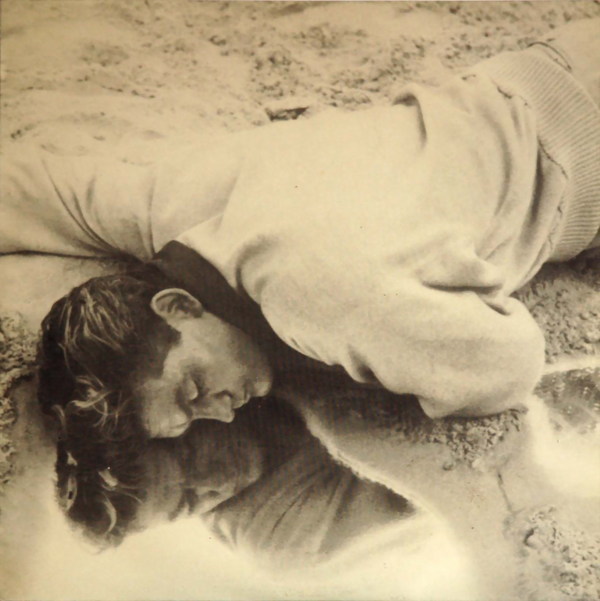

I find myself in slight disagreement with Emmy's typically excellent post on The Smiths and Owen's response to it (both of which were reacting to Tom Ewing's Pitchfork essay). It was the "instinctively" rather than the "anti-modern" that I bridled against in the original review. Morrissey has also struck me as anything but "instinctive"; his stances were always artful as much as heartfelt, everything very carefully arranged for the gaze of a redeeming Other (who, of course, would never arrive - Morrissey's compact with his audience, the little others who actually do listen and identify with him, depends on this consensual lack). Simon's characterisation of Morrissey as being like one of those awkward adolescents who turns up to teenage party only to show disdain perfectly the nature of Morrissey's narcissism of abjection. But I think it would be hard to deny that there was an anti-modernism in The Smiths. Certainly, Owen is right, Morrissey's antipathy might have been less to modernity as such than to the modern as it happened to turn out in Britain (with Thatcherism's championing of American-style consumer capitalism read as an attack on the Britishness Morrissey wanted to defend). Still, there's precious little enthusiasm for modernity of any kind in The Smiths; instead, Morrissey took refuge in a counter-modernity of the recent past. What he did was fuse elements from this near-past that might have seemed contradictory at the time (Dallesandro and Delaney, indeed) into a dreamed consistency, a kitchen sink Glam. The Morrissey that appealed to me was the queer Morrissey of the early records. There's a theory of queer to be extrapolated from from the refusal of sexuality, relationships and work on the likes of "You've Got Everything Now" and "Still Ill". After this, ruined by success, Morrissey would oscillate between earnestness and camp without ever attaining again the anguished high drama of his early assertion of incapacity as heroic failure.

Disavowal, left and right

- If there are avowed racists who have said, "I know that he is a Muslim and a terrorist, but I will vote for him anyway," there are surely also people on the left who say, "I know that he has sold out gay rights and Palestine, but he is still our redemption." I know very well, but still: this is the classic formulation of disavowal. - Judith Butler on Obama (via)

Yet there is a great difference between the two forms of disavowal - the right wing disavowal is pragmatic. In fact it is questionable whether it is disavowal at all so much as a weighing up of perceived costs and benefits. In any case, it is not a fetishist disavowal in that it doesn't take the form of acknowledging facts only to act as if they were not the case. "Facts" are acknowledged, but they are deemed to be of less significance than other considerations. That they are not "facts" at all highlights another key difference between these forms of denial: for the right wing disavowal, fantasy lies on the side of the "facts" ("Obama is a Muslim and a terrorist"); for the left, fantasy is on the side of the affirmation "he is our redemption". That is why the leftist disavowal is certainly of the fetishist type - the point being that "selling out Palestine" really does contradict "redemption" while "being a terrorist" does not preclude Obama being "better for the economy". The leftist formula is properly fantasmatic in that it is an affirmation made in spite of the facts, while the right wing disavowal probably indicates the realignment of political priorities which allowed Obama to win: a new willingness to set aside the neoconservative agenda, while maintaining the commitment to neoliberalism.