July 18, 2008

July 15, 2008

Ghost Modernism

"I am very lucky to be in the possession of what I at times think of as a 'haunted' camera," Clean Eyes wrote to me, in response to my somewhat cursory observations on photography in the 2012/ hauntology post. "To give you some empirical info," he continues, "I am very much an amateur, I don't develop the work myself and to my knowledge it is only the eccentricities of the machine I use which create such occasionally uncanny results."

Clean Eyes' pictures of cities as construction sites have a deep resonance with Marshall Berman's All That Is Solid That Melts Into Air, which I'm ashamed to say I read for the first time only very recently, prompted by its being used as the epigraph to Jon Savage's Joy Division documentary. Berman's observations on the interplay of modernism, modernity and modernization, in fact, were roughly contemporaneous with the shift into post-Fordism at the end of the 70s that Joy Division's records converted into harrowing black and white expressionism. Berman's own first encounter with modernization was early, and traumatic: he had seen his own neigbourhood in the Bronx literally cut in two by a cubistic expressway driven through by architect Robert Moses, whom he characterises as "the latest in a long line of titanic builders and destroyers", including Louis XIV, Peter the Great, Stalin, Faust, Ahab, Kurtz, Citizen Kane. "For ten years, through the 1950s and early 1960s," Berman remembered, "the center of the Bronx was pounded and blasted and smashed. My friends and I would stand on the parapet of the Grand Concourse, where 174th Street had been, and survey the work's progress – the immense steam shovels and bulldozers and timber and steel beams, the hundreds of workers in their variously colored hard hats, the giant cranes reaching far above the Bronx's tallest roofs, the dynamite blasts and tremors, the wild, jagged crags of rock newly torn, the vistas of devastation stretching for miles to the east and as far as the eye could see – and marvel to see our very ordinary nice neighborhood transformed into sublime, spectacular ruins."

Yet Berman's response to modernization - and to Moses - is valuable because of its nuance: the Moses expressway is not the sole route that modernization could take, although - in a gambit that will become characteristic of neoliberalism - it presents itself as such. To resist such developments was, its opponents were bullyingly told, to stand against modernization itself; but Berman wants to keep hold of another modernism - a modernism not of the motorway, but of the street and the public space. His account of modernism is above all an account of different streets: Baudelaire's (and later Benjamin's) Paris boulevards; the Nevsky Prospect in Petersburg, where Gogol's characters wandered in a phantasmagoric haze and Dostoyevsky's Underground Man challenged the officer, his supposed superior, and in that challenge - pathetic and hopeless as it at first sight seems - made himself and a whole hierarchical social structure suddenly visible, and hence capable of being overturned.

Berman was deeply suspicious of postmodern theory, because he thought that modernity had not been superceded. What he couldn't quite see in 1982 - it would take Jameson and Harvey's interventions later in the decade to demonstrate this - was the way in which the modernist expressway would lead into the cul-de-sac of postmodernism, in which perpetual instability - "they are rebuilding the city, yes always" - becomes decoupled from cultural innovation. When all that is solid melts into air, the eventual result is not the sublime decimation that Berman witnessed in the Bronx, but the lure of simulation: Dick's reconstructed small town America and Prince Charles' ye olde English villages lie ahead, their "timeless charm" covering over the implacable churn of the abyssal excavators always working behind the screens.

the busier you are/ the less you see

Jane Jacobs emerges in Berman's account as an ambivalent figure. She is a corrective to Robert Moses's Kanesianism, her delineations of "the ecology and phenomenology of the sidewalks" a woman's-eye alternative to the Olympian planners' gaze which conceives of people as an obstruction, as Moses did. (As Berman reconstructs it, Jacobs' vision of the city as "a vast informal network" of shopkeepers and tradespeople, of a cycle of tiny routines, reminds me of nothing so much as Grace Jones' "The Apple Stretching".) At the same time, though, Berman recognised that the "undertow of nostalgia for a family and a neighborhood in which the self could be securely embedded" in Jacobs' work make it ripe for appropriation by the New Right. Hence Jacobs' pivotal role - alongside Jonathan Raban's Soft City - in Harvey's The Condition Of Postmodernity later. Their quiet polemic against planning, their celebration of the city as a shifting dance, helps to prepare the way for a postmodernism which has photoshopped out the kind of public and popular modernism which Berman celebrated. Jacobs' emphasis on a "feminine" city and the domestic sphere presage an ideological shift - the occlusion of the public by the family (which is resurgent at the level of ideology in part because it is shattered empirically). There's a great deal still to be said about the way in which a certain "feminisation" of culture - the fixation on emotions, domesticity and personal grooming - has been essential to the ideological destruction of the concept of the public over the last thirty years.

So we're back to hauntology. And Berman was already there, in 1982, when, as his book moves towards its close, he is calling up ghosts - not rural revenants, but the ghosts of past modernisms and their unfulfilled promises: he ruefully notes that, part of what was destroyed by Moses' expressway was nothing other than older versions of modernism. In his introduction, Berman invokes Brasilia, a city, like Petersburg, built ex nihilo - but without any public squares. Once it was the dictators who sought to eliminate public space; but the destroyer of public space now, cloaked in the language of 'choice', 'diversity' and 'interaction', is the wireless capsule of the unpiloted OedIPod...

Wel-come to Liberty City...

July 06, 2008

Dead to the wordly

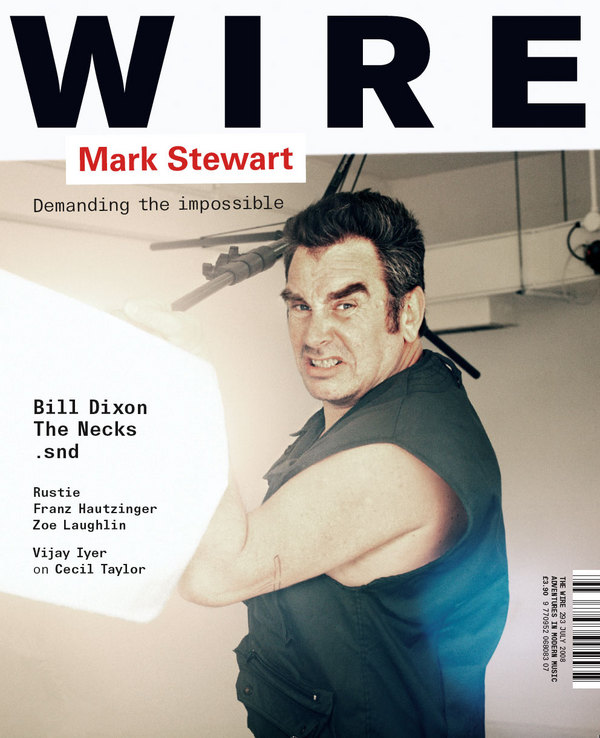

(being a belated plug for the July issue of The Wire)

"I grew up in a family where psychic stuff was normal," Mark Stewart told me when I interviewed him for The Wire. "My grandmother was a clairvoyant and we would have sessions every Sunday when we were kids." I didn't end up including this in the feature, but it strikes me that one link between the post-punk trio I wrote about in the July issue (Stewart, Mark E Smith, Ian Curtis) is channeling. In order to get at what is at stake in so-called psychic phenomena (and its relationship to performance and writing), it's necessary to chart a middle course between credulous belief in the supernatural and the tendency to relegate any such discussion to metaphor: being taken over by other voices is a real process, even if there is no spiritual substance.

The most disquieting section of the Joy Division documentary is the cassette recording of Curtis being hypnotised. It's disturbing, in part because you suspect that it is many ways the key to Curtis's art of performance: his capacity to evacuate his self, to "travel far and wide through many different times". You don't have to believe that he has been regressed into a past life in order to recognise that he is not there, that he has gone somewhere else: you can hear the absence in Curtis's comatoned voice, stripped of familiar emotional textures. He has gone to some ur-zone where Law is written, the Land Of The Dead. Hence another take on the old 'death of the author' riff: the real author is the one who can break the connection with his lifeworld self, become a shell and a conduit which other voices, outside forces, can temporarily occupy.

Mark E Smith once understood this very well; perhaps still understands it, even now, sitting at the bar at the end of the universe, his psychic antenna dulled by booze. In a very different way to Curtis, Smith at his most incendiary was a depersonalised host for stray, strange signal. Where Curtis's dispossession was concentrated into a single and singular voice that sounded as if it was already dead, Smith became a cacophony, an 'ESP medium of discord', a damaged transmitter that was like Baudrillard's schizophrenic: a switching centre for all the networks of influence. That is partly why the Smith 'auto' 'biography' is so disappointing. Biography is an end of history form, deflationary and reductive in its rush to reassure us that it was always about people. The point that artists come to believe it it is all about them - and not about their ability to channel externalities which erased them - is usually the point at which they lose it.

The Joy Division documentary succeeds in a way that neither Control nor the Mark E Smith biography did not, precisely because it resists this biographical closure. It emphasises the difference - the absolute difference - between Curtis the biographical subject and Curtis the singer. Carl was right to say that, in Control, "Curtis isn’t seen from anyone’s perspective but his own". But 'his own perspective' is very far from being the subjectively destituted perspective of the music, the art. The naturalistic distance that Control adopts keeps us outside all that; with the result that the focus on Curtis makes him seem not sympathetic but self-centred, and inexplicably so. There's very little sense of what it was that captured him, what drove him and rode him, the dread-ful euphoric trips out of his self to which he was addicted.

Voices, de-naturalised voices ... Curtis, Stewart and Smith all deprive the voice of its homeliness and its worldliness. Curtis because his voice was so sepulchurally cold; Stewart because his voice is so hot, so inflammatory. Fire, speak with me ... As I try to argue in the Stewart feature, Stewart remains an incendiary presence live because of his ability to channel rage and utopian longings ("one spark can start a prairie fire"), to set aside the etiquette of 'being a person', someone who is self-possessed, as represented in the usual expressive repertoire of a singer. The sound of the impossible being demanded as a resistance to the dreary certainties of capitalist realism.