June 25, 2006

Predators and piglets: A week and a day in the unlife

Blogs are just online diaries

This is what I did last week when I wasn't at work.

Saturday Text from Bacteria Grrrll: 'Worst. Dr. Who. Eva!' Indeed: surely some sort of nadir reached with this smug exercise in PoMo. I've tried to ignore the familialism and emotional pornography, but that has become impossible in the second series. It's rigorously Oedipal - Oedipus is the myth of no myths (Oedipus first of all defeats the Sphinx in an apparent but short-lived victory for psychological realism); hence the faux psychological 'depth' of postmodernity (once we feared monsters, now we know it's all about eeeeemotions....) Heretically, I think that the 'whatever time you travel to, it's always postmodern' effect is not unrelated to Billie Piper; Tennant's disappointingly underwhelming performances so far have meant that the programme has been increasingly dominated by Piper, one consequence of which has been the de-Alienatization of the Doctor.

Monday Morning. Interview John Foxx.

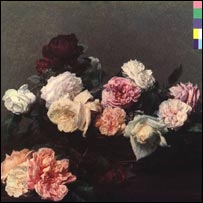

Evening. On the invitation of the excellent Jon Wozencroft, attend the launch event for Matthew Robertson's book on Factory and design. On the panel, Robertson, Peter Saville, Wilson, Pat Carroll (from Central Station, who did the Mondays' covers) and Rick Poyner. This notable for the schism it revealed in Factory (and, more broadly, in post-punk Manchester culture). Saville was the representative of the old pop-Modernist Manchester; Caroll, on the other hand, was a bluff, plain speaking spokesman for Ladchester. It is interesting to reflect on what was repressed in both cases. In Joy Division and early New Order it was ladsish carnality; at the time of the Mondays, it was artistic aspiration. But the Mondays weren't the Stone Roses (a band who always struck me as more Liverpool than Manchester in their sound and swagger), i.e. they weren't anti-Modernist rockists selling retro plod to students as the rave-inspired New Thing. The Mondays' transposition of Sly Stone and Krautrock into a Mancunian idiom, their translation of p-funk glossalalia into what Simon called 'dosser speak', was a mystical materialism - but they had to be sold as just ordinary lads, havin' a fookin laff, any weirdness played down, attributed to the pills... (One more way in which drugs, far from undermining the reality principle, tend to shore it up...)

Caroll gives it plenty of cloth cap, plays to the anti-intellectual gallery, gets laughs. Peter Saville marginalized, literally, his chair edging further and further to the side of the stage as the evening wears on. Wilson as slimily middlebrow as ever. This 'we didn't run a business' thing always struck me as middle class hippie indulgence; OK for you Tony, with your day job, but what about the artists?

Afterwards, am introduced to Richard Boon. Drunk, boring and boorish. Godfather of punk Boon sneers that blogs are 'meaningless' because there is no 'validation'.

Old man ... you watch me walk away...

Tuesday Zizek in the p.m. (And, incidentally, folks: I have sat next to Daniel at these lectures, and I can confirm that his uncannily accurate transcriptions do come from his own - really quite sparse - notes, not from any recordings.) Z is in a blistering form, eviscerating the liberal Left, prompting tediously drawn out immuno-response from the floor by Neg Dialectical harridan. I ask Z about taking over the State - he thinks we should do it, I think we shouldn't. I think Badiou's point about 'distance from the State' is crucial; this different both from Old Left Statism, and D/G type nomadology Obviously, there are long discussions to be had about this. Have one with Owen on the way home. Briefly, my claim would be that there is no way of taking over the State without the form of the State taking over you. Why not lose sentimental attachment to revolutions that have failed, and learn lessons from one that has succeeded (the neoliberal revolution)? To be continued, evidently...

WednesdayRead Tim Finney's Pitchfork review of Burial, after seeing the link on Blissblog. It's odd, Tim is one of the writers I most admire and pay heed to, but I often find my aesthetic judgements radically at odds with his. So it is here, since one of the things I most enjoy about the Burial album is its consistency, both of tone and quality. Love Simon's coinage (for dubstep) 'desolationist'. Note also that my New Statesman piece in 94, 'Hello Darkness', also paralleled jungle with isolationism.

See also Simon's review in Observer Music Monthly and Marcello's on Church of Me: delighted that Marcello appreciates the Burial LP; when I first heard it, I thought straight away, 'If ever there is a Church of Me record, it is this...'

Thursday

Watch Brazil huff and puff before eventually beating Japan. Anglo-Brazilophilia is a complement to post-56 transcendental defeatism (in which England's rapacious success as an imperial power is retrospectively read as a history of heroic failure). Brazil feature in the post-colonialist imaginary as noble savages, throbbing with samba rhythms, their exuberance the complement to our rationing pragmatism and monochrome dullness. Interesting to watch this religious faith start to crumble. For at least the last twenty years, probably longer, 'Real Brazil' has meant aged technicolour images from 1970, which are defiled by the sporadically brilliant, often ineffective, sometimes mediocre performances of the team on the pitch. The sacralized Image of Brazil is kept alive by treating most of what they actually do as an anomaly, a deviation from the Reality (i.e. the fantasy). But their mediocrity is now so glaring that even the most dedicated keepers of the flame are having trouble maintaining the Faith.

Compare Pele to Ronaldo. Pele featured in the Brazilophile imaginary as the a figure of non-utile excess, a carefree artist in the Nietzschean sense, indifferent to the narrow teleology of winning matches ... check the way that most of the endlessly replayed footage we see of Pele is not of him scoring goals, but audaciously missing chances contrived by force of wit. Ronaldo (like Romario) before him is the metonym of the post-94 Brazil; a clinical technician, a jaded assassin, his very boredom and overweight diffidence part of the camouflage that make him so effective. Catatonia and rush.

Whereas Pele - in the fantasy - stood for the plucky and the poor against the established and the staid, Ronaldo's goals now are strikes for the Reality Principle, signs that the undeserving and the lazy, the moneyed and the mighty, will always win in the end. Watching him, I'm reminded of Houllebecq's description of predatory animals in Atomised. 'Graceful animals like gazelles and the antelopes spent their days in abject terror while lions and panthers lived out their lives in listless imbecility punctuated by explosive bursts of cruelty. They slaughtered weaker animals; dismembered and devoured the sick and old, before falling back into a brutish sleep where the only activity was that of the parasites feeding on them from within.'

British commentators are sniffy about Ronaldo, no doubt because he is so besmirches their Ideal (of) Brazil. The Brazillian squad, managers and press, however, know that Ronaldo (even if 60% fit) is essential; without him, Brazil occasionally showboat without product, but mostly just labour unattractively.

Friday night in the city of the dead. Go to Forward at the End. Tottenham Court Road at 11.30 - all the alcohol zombies lurching and swaying... Hell is a city on earth, the yelps and howls of pleasure indistinguishable from the screams of the damned... Inside the End, it gets worse. With I.T. and a sceptical Bat. All Bat's prejudices about Dubstep confirmed by murky boy-heavy atmosphere. Sound like porridge. Bottom end sludge. Bat says it's because the EQ is set up for techno. Vague but pervasive sense of dope smoker menace. Leave early, reflecting on how much better in every way DMZ is... On the night bus, half-asleep, drift into a Schreber delirium in which my entrails are pulled out...

Saturday

Brockley summer fair at Hilly Fields. Exhausted, and this is the perfect environment for convalescence. In the bucolic sunlight, looking down on the rest of the city, it's possible to fall into a languid revery about Brockley as a racially mixed utopia.

And I.T. gets to handle a piglet...

Infinite thinking with pigs:

- Fairs in which pigs were the sole or principal commodity were extremely rare in England and in Europe generally, largely because unlike sheep, horses and cattle, pigs cannot be driven over long distances, and so were usually disposed of at small, weekly markets ... On the other hand the symbolic importance of the pig at the fair and its long association with the festive scene have tempted commentators to view the pig and its 'low' significance as a fixed, transhistorical notion going back to 'time out of mind.'

- ... Bakhtin's major advance in 'thinking pigs' was to recognize that the pig, like the fair itself, had in the past been celebrated as well as reviled. It was precisely the ambivalence of the pig, at the intersection of a number of important cultural and symbolic thresholds, which had traditionally made it a useful animal to think with.

- Peter Stalllybrass and Allon White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression

June 23, 2006

What is Philosophy? event cancelled

Important news for anyone who was planning to go to the What is Philosophy? event at Warwick tomorrow. Due to Jake Chapman being ill, the event has now been cancelled. Further details on the cancellation are here.

June 19, 2006

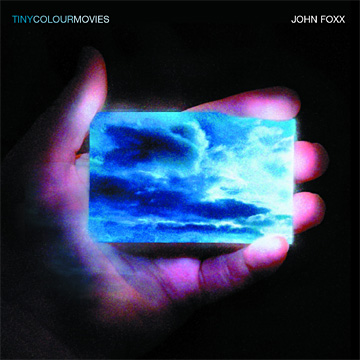

'old sunlight from other times and other lives': John Foxx's Tiny Colour Movies

- He was in the market crowds, wearing a shabby brown suit. Trying to find me through all the years. My ghost coming home. How do you get home through all the years? No passport, no photo possible. No resemblance to anyone living or dead. Tenderly peering into windows

John Foxx's latest LP, Tiny Colour Movies, is a welcome addition to this year's rich cache of hauntological releases.

Foxx's music has always had an intimate relationship with film. Like sound recording, photography - with its capturing of lost moments, its presentation of absences - has an inherently hauntological dimension. It wouldn't be an exaggeration to say that Foxx's entire musical career has been about relating the hauntology of the visual with the hauntology of sound, transposing the eerie calmness and stillness of photography and painting onto the passional agitation of rock.

In the case of Tiny Colour Movies, the relationship between the visual and the sonic is an explicit motivating factor. The inspiration for the album was the film collection of Arnold Weizcs-Bryant. Weicz-Bryant collects only films that are short - no movie in his collection is longer than eight minutes long - and that have been 'made outside commercial consideration for the sheer pleasure of film. This category can include found film, the home movie, the repurposed movie fragment.' The album emerged when, a few weeks after he attended a showing of some of Weicz-Bryant's films in Baltimore, Foxx found himself unable to forget 'the beauty and strangeness' of Weicz-Byrant's movies - 'juxtapositions of underwater automobiles, the highways of Los Angeles, movies made from smoke and light, discarded surveillance footage from 1964 New York hotel rooms' - so he decided 'to give in to it - to see what would happen if [he] made a small collection of musical pieces using the memory of those Tiny Colour Movies.'

The result is Foxx's most (un)timely LP since 1980's Metamatic. Tiny Colour Movies fits right into the out of joint time of hauntology. Belbury Poly's Jim Jupp cites Metamatic as a major touchstone, and time has bent so that the influence and the influenced now share an uncanny contemporaneity. Certainly, many of the tracks on Tiny Colour Movies - synthetic but oneiric, psychedelic but artificial - resemble Ghost Box releases. This is an electronic sound removed from the hustle and bustle of the Present. An obvious comparison for a track like the majestically mournful 'Skyscraper' would be Vangelis' Blade Runner soundtrack, but, in the main, the synthetic textures are relieved from the pressure of signifying the Future. Instead, they evoke a timeless Now where the urgencies of the present have been suspended. Some of the best tracks - especially the closing quartet of 'Shadow City', 'Interlude', 'Thought Experiment' and 'Hand Held Skies' - are slivers of sheer atmosphere, delicate and slight. They are gateways to what heronbone used to call 'slowtime', a time of meditative detachment from the commotions of the current.

- I constantly feel a distant kind of longing. The longest song, the song of longing. I walk the same streets like a fading ghost. Flickering grey suit. The same avenues, squares, parks, collonades, like a ghost. Over the years I find places I can go through, some process of recognition. Remnants of other almost forgotten places. Always returning.

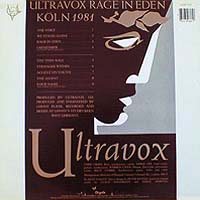

Tiny Colour Movies is a distillation of an aesthetic Foxx has dedicatedly explored since Ultravox's Systems of Romance. Although Foxx is most associated with a future-shocked amnesiac catatonia ('I used to remember/ now it's all gone/ world war something/ we were somebody's sons'), there has always been another trance-mode - more beatific and gently blissful, but no less impersonal or machinic - operative in Foxx's sound, even on the McLuhanite Metamatic.

Psychedelia had explicitly emerged as a reference point on Systems of Romance (1978) - particularly on tracks such as 'When You Walk Through Me' and 'Maximum Acceleration', with their imagery of liquifying cities and melting time ('locations change/ the angles change/ even the streets get re-arranged'). There might have been the occasional nod to the psychedelia of the past - 'When You Walk Through Me' stole the drum pattern from 'Tomorrow Never Knows' on, for instance - but Systems of Romance was remarkable for its attempt to repeat psychedelia 'in-becoming' rather than through plodding re-iteration. Foxx's psychedelia was sober, clean-shaven, dressed in smartly anonymous Magritte suits; its locale, elegantly overgrown cities from the dreams of Wells, Delvaux and Ernst.

The reference to Delvaux and Ernst is not idle, since Foxx's songs, like Ballard's stories and novels, often seemed to take place inside Surrealist paintings. This is not only a matter of imagery, but also of mood and tone (or, catatone); there is a certain languor, a radically depersonalised serenity on loan from dreams here. 'If anything,' Ballard wrote in his 1966 essay on Surrealism, 'Coming of the Unconscious', 'surrealist painting has one dominant characteristic: a glassy isolation, as if all the objects in its landscapes had been drained of their emotional associations, the accretions of sentiment and common usage.' It's not surprising that Surrealism should so often turn up as a reference in Psychedelia's 'derangement of the senses'.

The derangement in Foxx's psychedelia has always been a gentle affair, disquieting in its very quietude. That is perhaps because the machinery of perceptual re-engineering seemed to be painting, photography and fiction more than drugs per se. One suspects that the psychotropic agent most active on/in Foxx's sensibility is light. As he explained in this interview from 1983: 'some people at certain times seem to have a light inside them, it's just a feeling you get about someone, it's kind of radiance - and it's something that's always intrigued me - it's something I've covered before in songs like 'Slow Motion' and 'When You Walk Through Me'. I like that feeling of calm....It's like William Burroughs summed it up perfectly - 'I had a feeling of stillness and wonder."'

There is a clear Gnostic dimension to this. For the Gnostics, the World was both heavy and dark, and you got a glimpse of the Outside through glimmers and shimmers (two recurrent words in Foxx's vocabulary). Around the time of Systems of Romance, Foxx's cover art shifted from harsh Warhol/Heartfield cut/paste towards gentle detournements of Renaissance paintings. What Foxx appeared to discover in Da Vinci and Boticelli is a Catholicism divested not only of pagan carnality but of the suffering figure of Christ, and returned to an impersonal Gnostic encounter with radiance and luminescence.

What is suppressed in postmodern culture is not the Dark but the Light side. We are far more comfortable with demons than angels. Whereas the demonic appears cool and sexy, the angelic is deemed to be embarrassing and sentimental. (Wim Wenders' excruciatingly cloying and portentous Wings of Desire is perhaps the most spectacular failed contemporary attempt to render the angelic). Yet, as Rudolf Otto establishes in The Idea of the Holy, encounters with angels are as disturbing, traumatic and overwhelming as encounters with demons. After all, what could be more shattering, unassimilable and incomprehensible in our hyper-stressed, constantly disappointing and overstimulated lives, than the sensation of calm joy? Otto, a conservative Christian, argued that all religious experience has its roots in what is initially misrecognized as 'daemonic dread'; he saw encounters with ghosts, similarly, as a perverted version of what the Christian person would experience religiously. But Otto's account is a reterritorialization, an attempt to fit the abstract and traumatic encounter with 'angels' and 'demons' into a settled field of meaning.

Otto's word for religious experience is the numinous. But perhaps we can rescue the numinous from the religious. Otto delineates many variants of the numinous; the most familiar to us now would be 'spasms and convulsions' leading to 'the strangest excitements, to intoxicated frenzy, to transport, and to ecstasy'. But far more uncanny in the ultra-agitated, Dionysiac Present is that mode of the numinous which 'come(s) sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship.' Foxx's instrumental music - on Tiny Colour Movies and on the three Cathedral Oceans CDs, and with Harold Budd on the Transluscence and Drift Music LPs - has been eerily successful in rendering this alien tranquililty. On Transluscence in particular, where Budd's limpid piano chords hang like dust subtly diffusing in sunlight, you can feel your nervous system slowing to a reptile placidity. This is not an inner but Outer calm; not a discovery of a cheap New Age 'real' Self , but a positive alienation, in which the cold pastoral freezing into a tableau is experienced as a release from identity.

Dun Scotus' concept of the haecceity - the 'here and now' - seems particularly aposite here. Deleuze and Guattari seize upon this in A Thousand Plateaus as a depersonalized mode of individuation in which everything - the breath of the wind, the quality of the light - plays a part. A certain use of film - think, particularly, of the aching stillness in Kubrick and Tarkovsky - seems especially set up to attune us to hacceity; as does the polaroid, a capturing of a haecceity which is itself a haecceity.

The impersonal melancholy that Tiny Colour Movies produces is similar to the oddly wrenching affect you get from a site like Found Photos. It is precisely the decontextualized quality of these images, the fact that there is a discrepancy between the importance that the people in the photographs place upon what is happening and its complete irrelevance to us, which produces a charge that can be quietly overwhelming. Foxx wrote about this effect in his deeply moving short story, 'The Quiet Man' (Scanshifts and I used this at the start of our londonunderlondon broadcast last year). The figure is alone in a depopulated London, watching home movies made by people he never knew. 'He was fascinated by all the tiny intimate details of these films, the jerky figures waving from seaside and garden at weddings and birthdays and baptisms, records of whole families and their pets growing and changing through the years.'

'Here you see old sunlight from other times and other lives', Foxx observes in his evocative sleeve notes for Tiny Colour Movies. To leaf through other people's family photos, to see moments that were of intense emotional significance for them but which mean nothing to you, is, necessarily, to reflect on the times of high drama in your own life, and to achieve a kind of distance that is at once dispassionate and powerfully affecting. That is why the - beautifully, painfully - dilated moment in Tarkovsky's Stalker where the camera lingers over talismanic objects that were once saturated with meaning, but are now saturated only with water is for me the most moving scene in cinema. It is as if we are seeing the urgencies of our lives through the eyes of an Alien-God. Otto claims that the sense of the numinous is associated with feelings of our own fundamental worthlessness, experienced with a 'piercing acuteness [and] accompanied by the most uncompromising judgment of self-depreciation'. But, contrary to today's dominant Ego Psychology, which hectors us into reinforcing our sense of self (all the better to 'sell ourselves'), the awareness of our own Nothingness is of course a pre-requisite for a feeling of grace. There is a melancholy dimension to this grace precisely because it involves a radical distanciation from what is ordinarily most important to us.

- He stood in the soft beams of sunshine diffused by the curtains, caught for a moment in the stillness of the room, watching the dust swirling slowly golden through patches of light that fell across the carpets and furniture, feeling a strange closeness to the vanished woman. Being here and touching her possessions in the dusty intimacy of these rooms was like walking through her life, everything of her was here but for the physical presence, and in some ways that was the least important part of her for him.

Longing and aching are words that recur throughout Foxx's work. 'Blurred Girl' from Metamatic - its lovers 'standing close, never quite touching' - would almost be the perfect Lacanian love song, in which the desired object is always approached, never attained, and what is enjoyed is suspension, deferral and circulation around the object, rather than possession of it - 'are we running still? or are we standing still?' On Tiny Colour Machines, as on Cathedral Oceans and the LPs with Budd, where there are no words, this feeling of enjoyable melancholy is rendered by the minimally disturbed stillness and barely perturbed poise of the sounds themselves.

- I can detect tiny edges of time leaking through. I feel nothing is completely separate. At some point everything leaks into everything else. The trick is in finding the places. They are slowly moving. Drifting. You can only do this accidentally. If you set out to do it deliberately you will always fail.

- It is only when you remember, only then will you realise that you caught a glimpse. While you were talking to someone, or thinking of something else. When your attention was diverted. Just a hint, a glimmer, a shade.

- Much later, you will remember. Without really knowing why. Vague peripheral sensations gather. Some fraction of a long rhythm is beginning to be recognised. The hidden frequencies and tides of the city. Geometry of coincidence.

Listening to Tiny Colour Movies, as with all of Foxx's best records, one has a sense of returning to a dream-place. Foxx's shifting or shadow city, with its Ernst-like 'green arcades' and de Chirico colonnades, is urban space as seen from the unconscious on a derrive; an intensive space in which elements of London, Rome, Florence and other, more secret places are given an oneiric consistency.

I lost myself in that city more than twenty years ago.

- Sleeping in cheap boarding houses. A ghost with leaves in his pocket and no address. The good face half blind. A nebula of songs and memories slipping in and out of focus. Someone told me he was there but it didn't register at the time. The voice came unfocussed from all around. Still and quiet like the shadows of an ocean in the moving trees.

Indented text from the 'Quiet Man' story, 'Shifting City' and the Cathedral Oceans booklet.

STOP PRESS: I have just done a telephone interview with John Foxx, who was every bit as charming and fascinating as I'd expected... I'll try and post that in the next few days...

June 14, 2006

Hold-up of service...

... due to:

- Drowned World-like* oppressive humidity in London inducing lizard lethargy

- World Cup (see coverage by Philip of It's all in Your Mind here)

- being evacuated from my flat for 24 hours because of an explosion (apparently accidental) in one of the garages behind our house.

One reader wrote asking if I have abandoned the second part of The Fall piece. I have written most of it but will probably not have the opportunity to finish it before the end of this week. Most of today will be taken up writing my presentation for the Cultural Fictions conference, and I will be at that event on Thursday and Friday, so realistically there won't be many chances to write much before the weekend. However, I have nearly completed a piece on the brilliant new instrumental John Foxx LP, Tiny Colour Movies, and may be able to post that later today if everything else goes to plan.

Off the back of the X-Men posts, Myles Sullivan has some interesting observations on the current state of American comics:

- I remember as a young Catholic boy reading an issue of Excalibur where the Phoenix fought Galactus the Devourer of Planets. It was revealed that the Phoenix force derives its cosmic power by stealing the life force of those entities that are yet to be born across the universe. You can imagine how that rocked my world as a good little Catholic boy who had a taste for redheads.

- Marvel comics of late are very reactionary, almost neo-conservative. Many of the stories seem to be derrived from the fantasies of cruise missile-liberals and even run analagous to the brutal foreign policies of the US. Many of the heroes now exhibit facist enjoyment of torture and brutalisin enemies. See Ultimates, Authority, Wolverine etc.

- Instead of Nazis and Communists the superheroes now fight terrorists and insurgents-some are Muslim many are not, but this is just to disguise the blatant simplicity at work in the stories themselves-which do nothing more than mimic current events and violently simplifying evenmore that mainstream US corporate news.

- In the recent Marvel summer crossover title Civil War, a playground is blown up by a villain named Nitro. The government uses this as a opportunity to create a Super Hero Registration Act, etc. What is missing is the heroism of those on the margins, the mutants and the outcasts. Instead we have Wolverine hunting down Nitro (the next issue even appears to have Wolverine torturing the villain) while Spider Man and Iron Man work for the government!

- The comics I grew up with had the government and corporations as the villains. I can remember Rockefeller knock offs and industiral magnates as repulsive villains. Now these pigs are heroes, or finance them. American comics have become cynical and humorless-there is no devils laughter and the heroes are rotten with the perfection of the status quo.

- In the US right now I feel as if all of my childhood forms of fantasy have been assimilated by the military industrial complex-video games are even worse than comics. All media is being swallowed into this soft-fascist military/capitalist ideology.

- Here are some "trailers" for the Civil War "event".

- Maybe I am too sentimental, but I believe that because comics companies have become multimedia firms (trying to sell their products to film and game companies) and since their main audience is white men in their thirties, theyve shit the bucket and gone ever rightward. I've been visiting the comic book fan websites which do not even engage the characters as such, but discuss things along the libnes of potential stories that would be allowed by the markweting departments...the imagination is gone even among the fans.

- ... The adolescent and youth markets have migrated from American comics (I'd say starting in the mid to late 90s) and moved over to Manga and Anime.

- Many comics retailers in the States resent this for nationalistic as well as misogynistic and heterosexist reasons. Anime and manga often showcase bi and gay relationships and cast gender bending characters, as well as male characters who cry and are very emotional, but contain an incredible will to power, or will to survive--American comics characters seem to have no will to power to speak of, but then they dont need it, they die and come back to life every other issue.

*Speaking of Ballard, as we often do here, check this out ...

June 12, 2006

Cultural Fictions: the line-up

Cultural Fictions II

Sponsored by the AHRC and the Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths

All sessions held in the Small Hall (Cinema), Richard Hoggart Building (Main Building), Goldsmiths

Thursday 15th June

9:00 – 9:30

Registration

9:45 – 11:00

Greg Tate, ‘Closer to the Edit: Race Paper Scissors Islam Science Fiction’

11:15 –12:45

Panel #1: Potentialities

Owen Hatherley, ‘Art is a Branch of Mathematics': Zamyatin's Socio-Fantasy’

Wissam Mansour, ‘The End of Science Fiction With a Twist of Fiction’

Dene October, ‘The (Becoming wo)Man Who Fell to Earth’

12:45 – 1:45

Lunch

1:45 – 2:45

Anthony Joseph, ‘“Using the Future to Reconcile the Wrongs of the Past”: Building the African Origins of UFOs’

3:00 – 4:45

Panel #2: Sonic Science Fictions

Mark k-punk, ‘Consensual Hallucinations’

Susan Schuppli, ‘From Here to Eternity’

Mark Broughton, ‘Dyschronia in Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tape’

Steve Goodman, ‘Urban Delay: the Sonic Fiction of J.G. Ballard’

Friday 16th June

10:00 – 11:00

Roger Luckhurst, ‘Science Fiction: From Subculture to Network Portal’

11:15 – 12:45

Panel #3: Sci-phi

Nina Power, ‘Science Fiction and Philosophy in Kant, Sartre and Philip K. Dick: What Does the Extra-terrestrial Think We Are?’

James Burton, ‘Fabulation and Messianic Time: a Science Fictional Logic of Salvation’

Maeve Pearson, ‘Progeny: The Political Uses and Abuses of Childhood in Some Stories by Ursula Le Guin and Phillip K. Dick’

12:45 – 2:00

Lunch

2:00 – 3:00

Luciana Parisi, ‘Affective Sensorium’

3:15 – 4:50

Panel #4: Onto-mutations

Jessica Edwards, ‘“Running Out of Her Skin”: The Fold of Deep Time in the Black Female Body’

Oliver Belas, ‘“Transhumanism” and Metonymy in Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis’

Michael Metthey , ‘Nanotechnologies’

James Trafford, ‘Nanotechnics and SF Capital’

5.00 – 5:40

Final Panel: keynote speakers in discussion

Chair: Kodwo Eshun

5:50 – 6:30

Performance by Anthony Joseph and the Spasm Band

June 08, 2006

Phoenix as symptom

Some remarks (via email) by Nick Packwood allow me the opportunity to clarify a few things from the X-Men post:

- 'We learn, though, that there is no 'Jean Grey' the authentic Self, that the Jean Grey persona was itself always a 'screen identity' developed by Xavier to contain Phoenix. (And, naturally, all of our identities are negatively shaped by the deforming pulsions of the Death Drive.)'

-

I believe Professor X claims that the Phoenix is a consequence of the blocks he has put in place in order for the (adolescent) Jean Grey to contain/manage/control her powers.

Well, he would wouldn't he? :-) Xavier's formulation cries out for reversal: surely it is also Jean who is a 'consequence of the blocks [Xavier] has put in place'. The point is that Jean is as much an effect of the repression/creation of Phoenix as the other way around.

Nick continues:

- This does not render Jean Grey an inauthentic screen for the authentic Phoenix of the Id. It is, rather, a classic model of repression in the formation of an individual, and for that matter social, psyche. Yes, Jean Grey is more than her social face and yes this face masks seething desires. But such is precisely the discontent which makes Freud's psychology more interesting, and to my mind more credible, than Marx's utopianism.

- What I am saying here is that the Phoenix is as much a product of repression as Jean Grey; a dream projection onto those drives we can never know directly but only by indifference. In this sense, the Phoenix is a Symptom of containment rather than a positive Thing that is contained.

I in no way meant to suggest that Phoenix was more authentic than Jean Grey; that would be to subscribe to some hideous quasi-Lawrentian vitalism in which the 'real self' = inchoate desires kept pent up social convention. But it is precisely that model which is implied by claiming that 'Jean Grey is more than her social face and yes this face masks seething desires.' I would argue that, on the contrary, that Jean Grey is only the social face; and that the desires which seethe beneath that face (and shape it) are not dammed biologistic flux but an effect of the splitting, or spaltung, which is the primordial event of subjectivity. In other words, there is no authentic self of any kind; what is authentic is not either Jean or Phoenix but the spaltung. There is no Jean without (the repression of) Phoenix. At the same time, though, there is a radical asymmetry; Phoenix (as avatar of the Death Drive) is eternal because undead, whereas Jean is a particular mortal. But the Death Drive does not exist as some free-floating biologistic force; if it does not possess particular individual mortals, it is nothing.

Also check this: X-men, Badiou, Robespierre...

June 06, 2006

'Father, can't you see I'm burning?' The death drive in X-Men: The Last Stand

CONTAINS SPOILERS

|  |

There's a great deal to be said about the tremendous new X-Men film, (and much has already been said, very well, in Josef K's piece on Different Maps). By some distance the best film of the sequence so far, what is impressive about X Men: The Last Stand is that it dares to take itself seriously, avoiding the bad reflexivity of Pomo in favour of an unscreened exploration of a mythos. After all, the Pulp Unconscious of comics, populated by human-animal hybrids, is our closest equivalent to Greek or Roman myths, and thankfully, there is no Frank Miller style anti-mythic psychobiographical chin-rubbing in The Last Stand; this is not a film that tries to be 'psychologically realistic'. No, it is a film about the Real, that which we flee from when we awake from a dream. Thus it takes place in the apocalypses we encounter every night, in the endlessly collapsing and reconfiguring blue-black landscapes of nightmare.

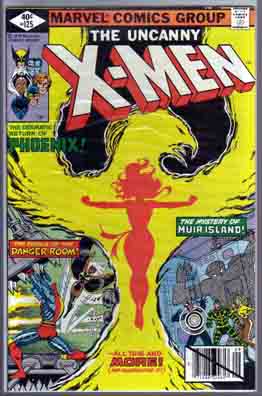

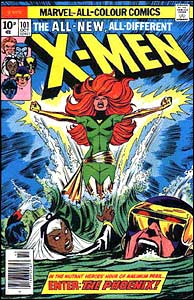

The Last Stand, like the New X-Men comics on which it is based, is dominated by the theme of death. (Long before the Phoenix story, on only their second mission, one of the New X-Men, Thuderbird, died in action.) Jean Grey had heroically died at the climax of the previous film, and The Last Stand risks bathos by having her return from the dead, as Phoenix. But any fears that the film would retrospectively cheapen the impact of the previous instalment by reviving Grey are quickly dispelled. The Last Stand is unwavering in its message that the return from is worse than death itself.

You may recall that last year that when I had to fill in a meme about what my superhero name would be, I, predictably, chose the name Death Drive. But Phoenix - not so much that which endlessly returns to life as that which cannot die - might as well be called Death Drive. In fact, you will not find a handier illustration of the distinction between the Death Drive and the desire to die than the opposition between Jean and Phoenix. Jean begs to die, whereas Phoenix is endlessly re-incarnating undead desire. Jean's wish to die is precisely, then, a wish to resist the Death Drive, to cease to be the meat puppet slave-shell inhabited by impersonal, inhuman, unliving desire.

The film is not only about phyical but also subjective-death - what is 'Jean Grey' if she is taken over by this uncontrollable, implacable force? (Conversely, what are Magneto or Mystique without their mutant powers?) We learn, though, that there is no 'Jean Grey' the authentic Self, that the Jean Grey persona was itself always a 'screen identity' developed by Xavier to contain Phoenix. (And, naturally, all of our identities are negatively shaped by the deforming pulsions of the Death Drive.)

|  |

Josef K rightly draws attention to the sexualized nature of the mutations and the implicit Queer politics of the film. The most traumatic and genuinely disturbing scene comes very early on:

- The teenage Warren Worthington (the X-Man Archangel) has locked himself in a bathroom and is breathing heavily. He is trying to cut off his wings with some rusty scissors. His father demands that he opens the door, "You've been in there for over an hour!" A panicked act of attempted concealment ensues, he opens the door, his father immediately understands, "Not you as well..."

This ambivalence of this scene is fascinating - on the one hand it functions as allegory of being caught in the act of masturbation (I made a similar parallel in my review of X-Men 2 - m k-p), on the other hand it seems to concern even more fundamentally the act of self-harm. Both noted patterns of teenage behaviour - and it seems to me that what the audience is being invited to understand here is that from a certain perspective (namely, that one of militant heteronormativism) these acts amount to the same act: sexuality (masturbation) as disease, as sin.

I couldn't help thinking, too, of the Birthday Party's 'Mutiny in Heaven' and the junkie-Cave's delirial scream, 'fucken wings burst out mah back (like ah was cuttin teeth!!)'. Transforming the body and mind through drugs is, needless to say, something else that parents dread teenagers are up to behind the locked bathroom door.

Observing the mutations of teen bodies through drugs and sex led recanting Marxist turned cultural conservative Leslie Fiedler to write of a 'feminization' of the young in his astonishingly prescient 1965 essay - which already referred to 'post-Modernism' and 'post-humanist sexuality' - 'The New Mutants' (the title of which lent itself to an X-Men spin off). For Fiedler, feminization initially appears as a kind of ultra-passivity, which immediately crosses over into schizophrenia; Fiedler is describing the spreading of a condition that someone like the psychotic Judge Schreber had already experienced back in the nineteenth century.

IT lookalike Rogue sporting 'badly home-dyed tribute to Billie Piper' hairstyle

Strafed by the rays of God, Schreber felt himself to be 'unmanned'. His delirium - echoed in the central image of the techno-invaginated Max in Cronenberg's Videodrome - was already telematic (but, then, isn't schizophrenia, its best known symptom the hearing of voices, an inherently telematic disorder?) The other side of the schizophrenic dread of being overwhelmed by a signal transmitted from outside is the terror of yourself becoming the transmitter. In both states, there is what Baudrillard characterized as 'the absolute proximity, the total instantaneity of things, the feeling of no defense, no retreat'. Not only Phoenix, but also Rogue is in horror of 'the unclean promiscuity of everything which touches, invests and penetrates without resistance' - precisely because she herself is the one whose touch is deadly, who can touch (and destroy) without resistance. Rogue therefore chooses subjective death - the elimination of her powers through the 'mutant cure' - in order to return to 'heterosexual normativity' via her relationship with Bobby Drake.

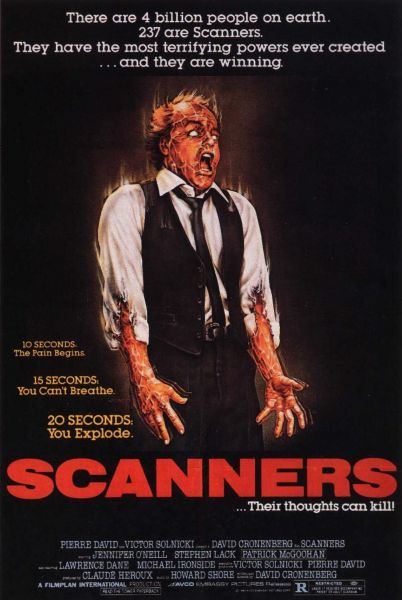

The best known film to deal with the dread of becoming a transmitter of lethal telekinetic signal is of course Cronenerg's Scanners. (Is it any accident, by the way, that Loefah samples Scanners in his dubstep favourite, 'Goat Stare'? Isn't the 'scanning experience' an analogue for being irradiated by bass waves?) Yet Scanners was in many ways a recapitulation of De Palma's underrated Fury, which itself refrained the theme of 'uncontrollable telekinetic power' in De Palma's previous, more celebrated, effort, Carrie.

|  |

The problem, in Carrie, Fury and The Last Stand is the failure of the Father. If, as Josef K persuasively suggests, The Last Stand re-presents, in the characters of Professor X and Magneto, the splitting of the Father into the Name of the Law and Pere Jouissance, then the film is remarkable for its refusal to vindicate either model of paternal authority. Both Fathers fail in their attempts to control, help or manipulate (and the film is very clear that these terms become interchangable) Phoenix; both, that is to say, cannot heed the cry of 'Father, can't you see I'm burning?' which her desire poses.

In the end, the only riposte to the unstoppable force of the Death Drive is the immovable object of love. It is tempting to read the highly affecting scene in which Wolverine kills Jean after being flayed by Phoenix's 'arrows of desire' as Eros winning out over Thanatos. In fact, Wolverine's love for Jean, as much as Phoenix's 'pure will, instinct, glee, rage', is beyond the pleasure principle. Earlier, Wolverine withdraws from a sexual encounter with the newly revived Phoenix (a scene that promised to be utterly Burroughsian: reality-warping psychic vortex fucks animal-warmachine cyborg), suppressing Eros in the interests of Agape. In his discussion of this scene, Josef K refers to Zizek's "I love you, but inexplicably I love something in you more than you, and therefore I destroy you." Yet, doesn't the scene present something that is almost the reverse of this? 'Even though you are totally possessed by something in you that is more than you, I still love you, and therefore I destroy you.'

June 05, 2006

Correspondence corner

Well, I'm back, but debilitated by illness, so I'll let readers take over for a while....

Chris Baylis writes:

- 'I was on the London underground last week visiting a friend (slices of bacon swinging from meat-hooks), surrounded by people with dead straight eyes gently nodding heads and drug white iPod wires stuck in there ears, when all of a sudden out of the I saw an advert rush by depicting a sheep wearing an iPod with the word "iSheep" on it. 'Thats strange' I thought, some kind of subvertising group advertising on the underground?

Today I visited the website [name of website]. At first I was enthralled (Yeah stick it to those iPod zombies etc) only to immediately realise that the website is a little to to well designed. Adbusters.com for instance is quite amauterish with a slow server speed. This website however has pretty graphics and slick animation. Upon reading some of its faux anti-corporate propaganda I clicked on the last window option in the list entitled "The Alternative" written in graphics that drip like fresh spray paint. I shall quote:

"So here it is the [name of product]"

You should do a post about this with lots of neologisms, quotes from Delueze and things like "This is hyperstitional coopted conformity semiotic dialectics presented as the new consensual hyper reality reflexive impotant schizogenic cybernesis. The mediaspheres alien brain parasite entity internodal affect with parareality."

Lol...

An American correspondent who would like to remain anonymous writes:

- Speaking of managerial solutions and ideology, my boss subjects me to that nonsense every day. I do security at the school library. A knife fight at the front door is not a problem, but someone opening the doors to the garden IS a problem. Another one: there is a patron who insults me every shift and is trying to instigate me to hit him. Instead of banning this asshole they offer me courses in how to deal with difficult customers and maintain "inner calm". Try yoga? Haha.

And Josef K from Different Maps forwards me news of a 'Hauntology month' at the Horse Hospital. The connections with hauntology seem a bit tenuous in many cases (well, the Horse Hospital was one of the principal inspirations for some of the invective in Pomophobia), but some of the events look like they might be worth checking out.

Dejan Nikolic writes:

- there's something you don't seem to understand and I, as a cultural parodist, simply must explain:

it is not only Minghella who shifted the dynamic from class to sexuality - it is Zizek, too. If you read his review of Talented Ripley you will see that the observations he makes never touch upon the issue of class, focusing instead on a critique of the film's representation of Ripley's sexual identity etc. And Minghella's adaptation is repulsive precisely because it wants us to share Ripley's admiration of the rich and persists in making us feel guilty about the death of characters like Gwyneth Partlow.

Zizek speaks from the position of a (Slovenian) neo-liberal and social-democrat. He always wanted to be with the rich capitalists, and he speaks the same doublespeak that he later deconstructs in his lectures.

And this ''Marxist circle of Christians'' that he seems to be building sounds like something straight from Hell!

lol again, but it seems to me that Zizek's review of the film took its cue from Minghella. The problem with most of Zizek's discussions of Highsmith, actually, (cf his London Review of Books piece on the Highsmith biography) is that they end up being about the film adaptations rather than about Highsmith's own texts. As is increasingly the case with Zizek's texts (but in contrast with the admirable focus of the current lecture series at Birkbeck), there are a few tantalising references to specific novels before he is off again, recounting old jokes or making remarks about films. Still, if he managed to produce a sustained account of Highsmith, there would be no need for I.T. and me to do one...

Meanwhile: reports on the Thursday Zizek lecture from Different Maps and Sit Down Man, You're a Bloody Tragedy: I missed it, I'm afraid, in order to endure the gruesome yet soporific spectacle of Badiou being pushed through the Continental Philosophy boredom and gravity-machine at Middlesex.

June 02, 2006

In the meantime...

|

I'll be away until Sunday evening. To keep you entertained until I return, the online version of my interview with Peter Saville is now available here. (This is the extended version - but there are still 10,000 very interesting words that didn't even make that!)

(btw, I'm pleased to see that Tim Wrong has caught the dubstep virus too...)