November 26, 2009

Beyond the Kettle and the Carnival-Protest

An example of how severe disagreement does not have to be trolling or grey vampirism: Philosophe Sans Oeuvre's response to my and others' exasperation in respect of the G20 protests. Instead of the troll or vampire's quisling retreat from taking a position, PSO very clearly sets out are a set of sincerities and refutable claims. I will respond to the post in the same spirit it was written - with a measure of knockabout sarcasm, but with also a comradely sense that this is not one more empty Web 2.0 'debate'. It is a discussion that urgently needs to happen. The effective opposition to the interpassivity of communicative capitalism is not some totalitarian authoritarianism, but purposive action. Discussion about the form that this purposive action should take is quite different from a 'debate' in which discussion is supposed to have value for its own sake - and of course that discussion is far better had with those who want to do things rather than engage in academic critique.

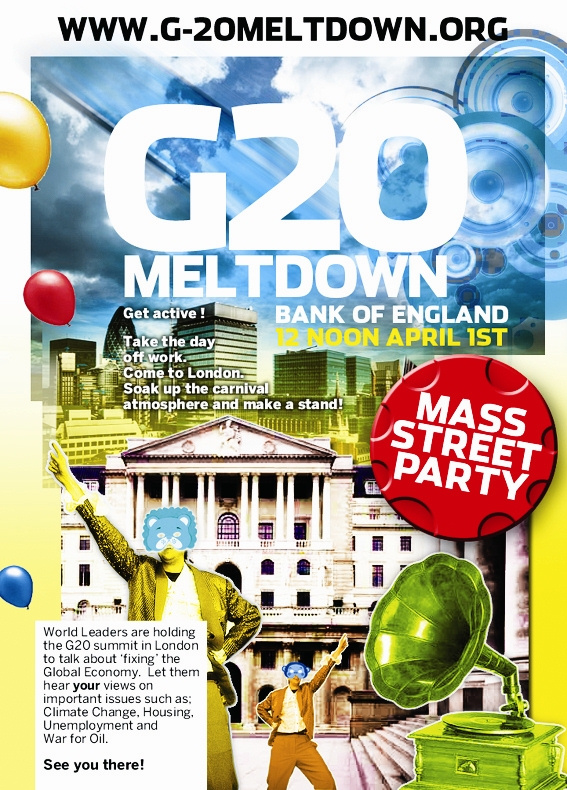

Nevertheless, I'm a little at a loss as to how PSO or his interloctuor, Paul Reed, answer my problems with the 'G20 Meltdown' since the substantive claims in favour of the protest seem to be unfalsifiable articles of faith: it felt good to be there, any 'activism' is a priori better than theory, we can't yet know what the effects of the protest will be (so if, as seems to be the case, the protests had no political effects whatsoever, don't worry, because it is too soon to tell - and it always will be, presumably...) Then there is the baffling claim that the protests were a success because they cost a lot of money. "The G20 Meltdown was ‘the most expensive protest in British history’, which is a good indication of its real potential: the British government could not afford to have another one like it." I'm not sure what this means - that government finances would collapse if another protest took place? Even if that improbable contingency were to come about, why would that be a good thing? Surely what is more likely is that the government will always find money for policing - and it will find it by taking it from other areas of public spending. I'm sure we can all think of better and more creative uses of public money than it being squandered on police overtime. If the point was to waste as much money as possible and to disrupt people going to work, then it's little surprise that - despite widespread anger about bankers, despite Tomlinson's death - that the media response was not an endorsement of the 'Meltdown', or that the protests failed to break down what Alex Williams has called 'negative solidarity' ('I have to work hard for poor wages, why are they complaining?'). The idea that the protests would have succeeded if it weren't for the pesky media is one of the strangest claims in the PSO post - surely media hostility and circumspection should have been expected and planned for?

Then there is the tired, self-aggrandising opposition between 'activists' and 'theorists' (an opposition being wielded here, as it so often is, by theorists themselves). If Nick, Alex, Reid and myself issued our writings on handbills in the street and organised protests that had no efficacy would we be suddenly elevated into the ranks of the Holy Activists? In point of fact, the only reason that I'm not an 'activist' is that I got 'made redundant' for being one - much of Capitalist Realism comes from my experiences as a Union member and organiser, which, amongst other things, led me to conclude that many forms of activism just haven't caught up with post-Fordism. I'm the last person to think that politics requires vindication from philosophy, or that 'workers' need to be organised 'from above'. What I do think is that 'workers' - whatever that word means now - do need to be organised, and that there must be new thought about what form that organisation might take. (Presumably, by the way, the G20 protests were in fact organised and co-ordinated: the rhetoric of the PSO post would have us believe that they were some direct, spontaneous outflow of the Will of the People - and belief in such spontaneism is itself a theoretical commitment, one of many egregious effects of certain post-68 tendencies in continental philosophy). Thought about organisation - not 'political theory' or 'political philosophy' as some empty academic exercise - is what I've been calling for. It' is a certain kind of 'action' which is the refuge of the beautiful soul now - especially the 'acting' which avoids engagement with institutions or the structure of work.

- There is no point in criticising a political strategy when you do not offer a political strategy or a political subject to replace it.

Well, there is a clear point, if the strategy is a waste of resources, or is counterproductive. Besides, of course, I and everyone else in the 'consensus' happen to have plenty of ideas about new political strategies.

As for the claim that "The folk-psychological reading of the protest is a facile interpretation of a complex event and grossly patronising to those that took part." I would reverse this: the folk-political form of the protest is a facile response to a complex phenonemon (capitalism). I've of course no doubt that many of the protestors have highy sophisticated understandings of capitalism, but that sophistication is not - and cannot be - reflected in the carnival/ protest model of political action. The problem is that there is a slide between the logic of protest and the logic of carnival: if there are no determinate demands, then that is because the point becomes a carnivalesque experience of street clamour. At the same time, the carnival is claimed to be more than a matter of 'feelgood-feelbad' affect because of its protest dimension. Protests certainly can work in particular circumstances. But a protest against capitalism seems designed to fail. Acting as if that is an agent who can meet the ill-defined demands cannot but be a matter of bad faith. Protests are petitions: who are what was this petition aimed at, and who or what could have met its demands? Let's imagine that all of the leaders at the G20 summit agreed to meet the protestors' demands - what would that have involved? My suspicion is that there was any real belief on anyone's part that the protests could have worked, nor was there any clear sense of what working woud even have meant - this isn't a left preparing to take power, but one that, in its heart of hearts, expects protest to follow protest forever, which is why such carnivalesque protest has been the background noise of capitalist realism, tuned out with increasing ease by the managerial and political elites. Beyond this, expectations peter out into fantasy, where the protests trigger a spontaneous revolt which will miraculously self-organise into a whole new society. But let's suppose that everyone in the world spontaneously decides that they don't want to live in capitalism any more. Even then - or rather especially then - the questions of organisation would impose themselves all the more forcefully.

Weight of numbers, and the kind of heterogeneous group that came together at the G20 Meltdown, can certainly be effective in labour disputes or occupations - where they are deployed against a particular point, instead of impotently and vaguely thrown at (a simulacrum of) Capital itself. (And, incidentally, if the point is to build alliances amongst the 'grass-roots anti-capitalist movement', why the gratuitous attacks on the SWP? Mustn't any "political theory which aligns itself on the Left" also "seek to draw on their support"?) There's surely a massive difference between the 'one day out of life' logic of G20 Meltdown and factory or university occupations. These latter involve both determinate demands and something more - the possibility of sustainable antagonisms, which can develop in the institutions where people actually work, as well as the 'practical sufficiency' of a collective will which demonstrates that it can organise work or education itself, without the need for the overpaid managers and executives.

One of many things that's haunted me from Andy Beckett's When The Lights Went Out is the account of the Grunwick dispute. Not so much the familar account of the struggles in front of the factory gates, as what the right did to break the strike behind the scenes - the so-called Pony Express operation that they organised to circumvent the postal blockade:

- The hundred thousand parcels had to be unloaded, individually weighed and stamped, then sorted by address and put back into mailbags for posting. There were 250 volunteers altogether ... It was hot in the barn, even with the door open. There was the odd Thermos of soup, tea or coffee, and an atmosphere like a particularly eager election count. 'It was revolting licking thousands of stamps,' Smith remembered, 'but there was a very strong sense that we had to get it done. The mail had to be out in the postboxes the next morning.'

- During the hours of Saturday, the finished sacks were loaded onto the smaller vehicles in the farmyard. 'Then the horseboxes and shooting brakes were despatched,' recalled Gouriet. They went down the long drive of Broadfield Farm, with instructions to deposit Grunwick's mail in modest, hopefully not-too-noticeable quantities at postboxes from Manchester to Truro. 'We were euphoric,' he said. It was the same spirit as in the war.'

I think this story shows many things: that the triumph of neoliberalism wasn't some inevitable law of History or Capital; that it happened not because of wealth alone, but because wealth was used as a resource to fund organisational strategies; that such such stragegies were often ingenious and experimental; that the activities themselves - buying and licking thousands of stamps, posting thousands of letters - were very far from being carnivalesque or enjoyable but that performing them produced a sense of euphoria. (One is tempted to say that the G20 melancholy carnival was the exact opposite of this: an ostensibly enjoyable party in the street that ended up as a boring and demoralising kettle, producing dysphoria in the bad sense, as Alex suggested.) Compare the hundreds of thousands on the street in the anti-capitalist protests of the last decade with what those 250 volunteers achieved. By helping to break the Grunwick strike, they did more than end one particular labour dispute - as with the defeat of the Miners Strike later, the Grunwick strikebreaking also functioned at the memetic and Symbolic level, preparing the way for capitalist realism. Pursuing winnable, determinate goals engenders a sense that winning is possible, which further reinforces the sense of conviction necessary for victory: a hyperstitional circuit. It's this kind of circuit that left activism needs.

Posted by mark at November 26, 2009 10:03 AM | TrackBack