January 09, 2005

Nihil Rebound: Joy Division

"If you shoot yourself, you'll become God, isn't that right?"

"Yes, I'll become God." – Dostoyevsky, The Devils

‘… [O]ut of the corner of my eye I saw him. He was kneeling in the kitchen. I was relieved – glad he was still there ‘Now what are you up to?’ I took a step towards him, about to speak. His head was bowed, his hands resting on the washing machine. I stared at him, he was so still. Then the rope – I hadn’t noticed the rope. The rope from the clothes rack was around his neck. I ran through to the sitting room and picked up the telephone. No, supposing I was wrong – another false alarm. I ran back to the kitchen and looked at his face – a long string of saliva hung from his mouth. Yes, he really had done it…’ - Deborah Curtis, Touching From a Distance: Ian Curtis and Joy Division, 133

So there it is, sublimation and desublimation. Suicide as Theological Art work (‘I’ll become God’), and suicide as a pathetic mess (‘a long string of saliva’) for someone else to clear up.

This post has been inevitable for over two decades.

But it has been given particular impetus by three recent encounters.

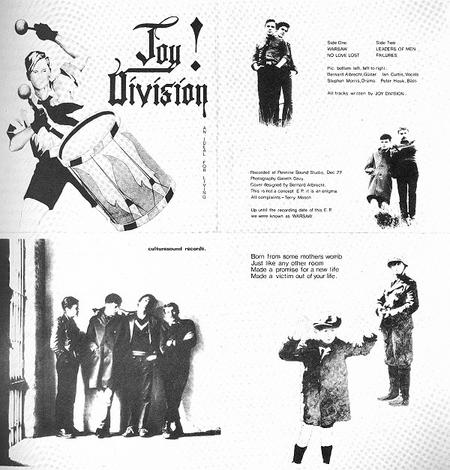

1. The NME’s Goth special, which, amongst other things, collects together the Joy Division reviews. Strange in many ways to see them canonized as Goth princes. There was no question of course that theirs was a fiercely expressionist sound – a sound in fact that was much more genuinely Gothic than that of the Caligari-faced panto turns who have appropriated the name or who have delighted in having had it foisted upon them. Yes, Joy Division, with the ‘witchy emptiness’ of the Pennines weighing heavy upon them, had produced what Jon Savage called ‘the definitive Northern Gothic statement’. They had transmuted what ‘the Manchester damp and the shadows and omen called into dread being by the hills and moors that lurked at the edge of their vision’ (Morley) into the darkest machine Pop, a terminus of the Gothic ‘Northern line’ in a Pop rigor mortified into anxious mechanism. Yet the austerity of Joy Division’s image – their staged refusal of Image – set them at odds with the post-Bowie mummery of the Banshees, the Cure, Bauhaus and their diminishing returns photocopy-of-photocopies offspring. They were Gothic, but not Goths, surely.

2. A conversation with Kodwo at the Noise conference, lines coming out of his pieces on Closer and Movement. Kodwo recognized that ‘moving on’ from Joy Division involved disavowal, in the strongest sense. ‘I can't help but feel this music as a missing part of my body, a part I sacrificed at the stake of Black British life.’ Joy Division were a cult, but a hermeticists’ cult, a cult of those who didn’t belong and who didn’t want to belong, a bedroom communion between those who would never meet.

New Order, more than anyone else, were in flight from the mausoleum edifice of Joy Division, and had finally achieved severance by 1990. The England world cup song, cavorting around with beery, leery Keith Allen, a man who for me more than any other personifies the quotidian masculinism of overground Brit bloke culture in the late eighties and nineties, was a consummate act of desublimation. This, in the end, was the ‘price of escaping [the] anxiety of influence (the influence of themselves).’ On Movement they were still in post-traumatic stress, frozen into a barely communicative trance (‘The noise that surrounds me/ so loud in my head…’) ‘They were moving towards an electronic post-punk fusion here for which there were simply no rules as yet. It's almost as if what they started here - on 'Doubts Even Here' and 'The Him' especially, with its churning, blizzard-against-the-windshield hail of sound - frightened them, and they pulled back towards something more manageable.’

3. A conversation with Mark Sinker at the k-punk/ Infinite Thought kristmas party. It was clear that Mark and I had were at opposite sides of an irrevocable break, or time-cut, a cultural chronos-chasm.

I didn’t hear Joy Division until 1982, so, for me, Curtis was always-already dead (the hanged man harbinger of the endlessly circulating no-time of non-live media). Mark however experienced the Curtis death ‘in becoming’ – as a closing down of possibilities that were then very much live, as a contingency not a Necessity, as mess, not Myth.

Even though I could hardly have been aware of it back then, in 1982 Pop was living off stored-up energy, playing out formulae and designs that had already been produced but were now discontinued. The source had expired, collapsed into a dead star named Ian Curtis. Curtis’ death warped everything in the Pop landscape, removing the urgency from the Modernist impulse to endlessly re-invent, providing an alibi for those who wanted to retrench, return.

Everything had already happened, though we didn’t know it yet. In fact, though, the retreat from punk modernism into postmodernism, from avant-Pop to New Pop, had been almost immediate, Mark claimed. ‘People thought they’d rather not have to hang themselves as part of their job, if possible.’

Asylyums with doors open wide

When I first heard Joy Division, aged 14, it was like that moment in In the Mouth of Madness when Sutter Cane forces John Trent to read the novel, the hyperfiction, in which he is already immersed: my whole future life, Good and Bad, intensely compacted into those deliReal sound images - Ballard, Burroughs, dub, disco, Gothic, antidepressants, psych wards, overdoses, slashed wrists. Way too much stim to even begin to assimilate. Even they didn’t understand what they were doing. How on earth could I, then?

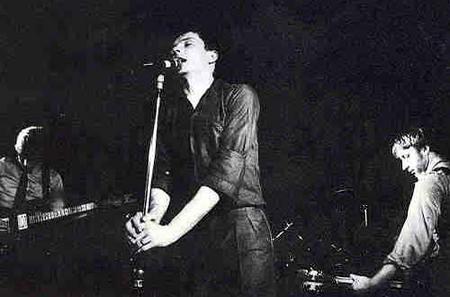

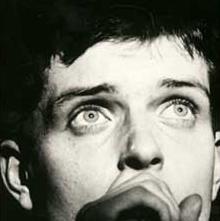

It was clear, in the best interviews the band ever gave - to Jon Savage, a decade and a half after Curtis’s death - that they had no idea what they were doing, and no desire to learn. Of Curtis’ disturbing-compelling hyper-charged stage trance spasms and of his disturbing-compelling catatonic downer words, they said nothing and asked nothing, for fear of destroying the magic. They were unwitting necromancers who had stumbled on a formula for channelling voices, apprentices without a sorcerer.

They saw themselves as mindless golems animated by Curtis’ vision(s). (Thus, when he died, they said that they felt they had lost their eyes…) As Mark put it in his piece on the early Eps in The Wire (over a decade ago!): ‘though the first bullying shards of Joy Division music are punk in sound, they don't clarify. This more than anything will become their signature - everything about them will be seized on, floridly discussed, and stay unexplained. Physical to a fault, the music exhibits all the the signs of the cerebral and none of its content - invention pours out of these dullard-geniuses, so stripped of hidden agendas that hidden agendas is all that many remark upon.’

Above all – and even if only because of audience reception - they were more than a Pop group, more than entertainment, that much is obvious. That’s why they are such an embarrassment, a part, yes, of our body we had to disclaim. We know all the words as if we wrote them ourselves, we followed stray hints in the lyrics out to all sorts of darker chambers, and listening to the albums now is like putting on a comfortable and familiar set of clothes….

But who is this ‘we’? Well, it might have been the last ‘we’ that a whole generation of not-quite-men could feel a part of. There was an odd universality available to Joy Division’s devotees (provided you were male of course). Look at those whom they left their mark upon, whom they still haunt: Savage, Morley (who has made an art out of not writing about them), Sinker, Eshun, Bohn, me. Gay, black, straight, white, postmodern, anti-postmodern: the point when you could count yourself one of Joy Division’s ‘we’ – ‘the sorrows we suffered and never were free’ – is prelapsarian now, a time before the straitjackets Identity Politics had tailor-made for us had been cooked up.

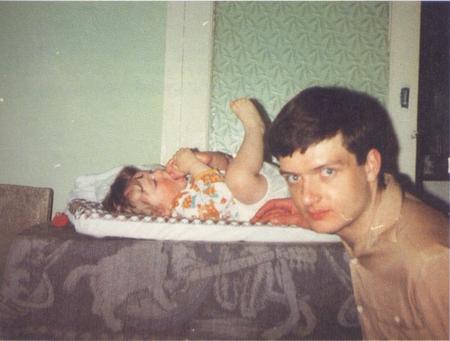

Provided you were male of course… The Joy Division religion was, self-consciously, a boys’ thing. The group wanted it that way and we, we colluded. Deborah Curtis: ‘Whether it was intentional or not, the wives and girlfriends had gradually been banished from all but the most local of gigs and a curious male bonding had taken place. The boys seemed to derive their fun from each other.’ (77) No girls allowed…

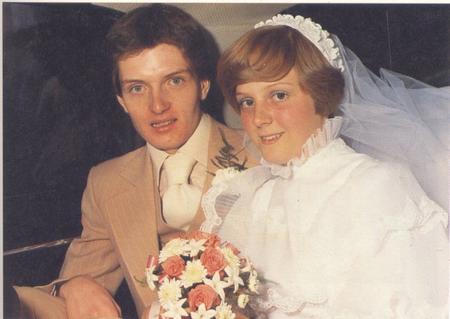

Ian and Deborah Curtis on their wedding day

In this colony

Try to imagine England in 1979 now…

Pre-VCR, pre-PC, pre-C4. Telephones far from ubiquitous (we didn’t have one till around 1980, I think). The postwar consensus disintegrating on black and white TV.

Simon wrote a year or so ago about ‘the sheer crapness of England in the late Seventies of Jim Callaghan and Grunwick and the Winter of Discontent, infusing everything from people’s clothes and hair to the advertising hoardings and pre-style culture drabness (the U.K. looks like an Eastern Bloc country).’ More than anyone else, Joy Division turned this dourness into a uniform that self-consciously signified absolute authenticity; the deliberately functional formality of their clothes seceding from Punk’s tribalized anti-Glamour, ‘depressives dressing for the Depression’(Deborah Curtis). It wasn’t for nothing that they were called ‘Warsaw’ when they started out.

But it was in this Eastern bloc of the mind (and of the political economy – after all, the UK in the Seventies, with its sclerotic nationalized industries, corrupt Sovietized Union power, and anti-commercial workerism, was much closer to the USSR than any of the British ruling class would then have liked to admit), it was in this slough of despond, that you could find working class kids who wrote songs steeped in Dostoyevsky, Conrad, Kafka, Burroughs, Ballard, kids who, without even thinking about it, were rigorous modernists who would have disdained repeating themselves, never mind disinterring and aping what had been done twenty, thirty years ago (the Sixties was a fading Pathe newsreel in 1979).

Chris Bohn’s claim that ‘Joy Division were making a music that was entirely white and European, which owed almost nothing to any rock past; that was their break with tradition’ is too simplistic, misleading because to discount altogether the immense influence on Joy Division of Morrison, Reed, Pop would be to miss how their Anglicization operated. You have to consider what happened to all these forebears in the Joy Division crucible. In effect, JD accelerated their becoming-European, took the Reed of Berlin and the Iggy who recorded in Berlin, took those starting points, which were already intersections, and subtracted what was left of the Americanness. Art Rock has always involved a flight from the terra firma what rockist rootists call authenticity, which is also what critics like Bangs and Marcus like to think of as quintessentially American. The only authenticity Joy Division craved was existential authenticity, something which, far from being inimical to artificiality, finds expression in it (there is no natural, Nature is still under production …)

Back in ’79, Art Rock still had a relationship to the sonic experimentation of the Black Atlantic, if only because it could be of use to it. Unthinkable now, but White Pop then was no stranger to the cutting edge, so a genuine trade was possible. Bowie and Roxy gave at least as much to the Black Atlantic as they took from it. And Joy Division provided the Black Atlantic with some conceptechnics, some fictions, it could re-deploy. Ask Grace Jones or Sleazy D.

For all that, Joy Division’s relationship to Black Pop was much more occluded than that of some of their peers. Postpunk’s break from lumpen punk r and r consisted in large part in an ostentatiously flagged return-reclaiming of Black Pop: funk and dub especially. There was none of that, on the surface at least, with Joy Division.

But a group like Pil’s take on dub, now, sounds a little laborious, a little literal, whereas, Joy Division, like The Fall, came off as a white anglo equivalent of dub. Both Joy Division and The Fall were ‘Black’ in the priorities and economies of their sound: bass-heavy and rhythm-driven.

This was dub not as a form, but a methodology, a legitimation for conceiving of sound-production as abstract engineering. But Joy Division also had a relationship to another super-synthetic, artily artificial ‘Black’ sound: disco. Again, it was they, better than PiL, who delivered the ‘Death Disco’ beat. As Savage loves to point out, the swarming syn-drums on ‘Insight’ (‘like a buzz of bees in the cortex’ – Bohn) seem to be borrowed from disco records like Amy Stewart’s ‘Knock on Wood’.

The role in all this of Martin Hannett, a producer who needs to be counted with the very greatest in Pop, cannot be underestimated and should not be undercelebrated. It is Hannett, alongside Peter Saville, the group’s sleeve designer, who ensured that Joy Division were more Art than Rock. The damp mist of insinuating uneasy listening Sound FX with which Hannett cloaked the mix, together with Saville’s depersonalising designs, meant that the group could be approached, not as an aggregation of individual expressive subjects, but as a conceptual consistency (what Kapital would call a brand – and btw Art Rock via Punk was one way in which UK Kapital would learn about the sexiness of corporate consistency).

It was Hannett (‘Eno's truest successor’ – Sinker) and Saville who transmuted the stroppy neuromantics of Warsaw into cyberpunks. Gibson’s world was Hannett’s and Saville’s more than it was Curtis’.

Set the controls for the heart of the black sun

What impressed and perturbed about JD was the fixatedness of their negativity. Unremitting wasn’t the word. Yes, Lou Reed and Iggy and Morrison and Jagger had dabbled in nihilism – but even with Iggy and Reed that had been ameliorated by the odd moment of exhilaration or at least there had been some explanation for their misery (sexual frustration, drugs).

What separated Joy Division from any of their predecessors, even the bleakest, was the lack of any apparent object-cause for their melancholia. (That’s what made it melancholia rather than melancholy, which has always been an acceptable, subtly sublime, delectation for men to relish.) From its very beginnings, (Robert Johnson, Sinatra) 20C Pop has been more to do with male (and female) sadness than elation. Yet, in the case of both the bluesman and the crooner, there is, at least ostensibly, a reason for the sorrow. Because Joy Division’s bleakness was without any specific cause, they crossed the line from the blue of sadness into the black of depression, passing into the ‘desert and wastelands’ where nothing brings either joy or sorrow. Zero affect.

No heat in Joy Division’s loins. They surveyed ‘the troubles and the evils of this world’ with the uncanny detachment of the neurasthenic. Curtis sang ‘I’ve lost the will to want more’ on ‘Insight’ but there was no sense that there had been any such will in the first place. Give their earliest songs a casual listen and you could easily mistake their tone for the curled lip spiky punk outrage, but, already, it is as if Curtis is not railing against injustice or corruption so much as marshalling them as evidence for a thesis that was, even then, firmly established in his mind.

Depression is, after all and above all, a theory about the world, about life.

The stupidity and venality of politicians (‘Leaders of Men’), the idiocy and cruelty of war (‘Walked in Line’) are pointed to as exhibits in a case against the world, against life, that is so overwhelming, so general, that to appeal to any particular instance seems superfluous. In any case, Curtis expects no more of himself than he does of others, he knows he cannot condemn from a moral high ground: he ‘let them use you/ for their own ends’ (‘Shadowplay’), he’ll let you take his place in a showdown (‘Heart and Soul’).

Depression is not sadness, not even a state of mind, it is a (neuro)philosophical (dis)position.

Beyond Pop’s bipolar oscillation between evanescent thrill and frustrated hedonism, beyond Jagger’s Miltonian Mephistopheleanism, beyond Iggy’s no-funhouse negated carny, beyond Roxy’s lounge lizard reptilian melancholy, beyond the pleasure principle altogether, Joy Division were the most Schopenhauerian of Rock groups, so much so that they barely belonged to Rock at all. Since they had so thoroughly stripped out Rock’s libidinal motor - ‘Sex has disappeared from these unknown pleasures; it is an aftermath of passion in which everything is (perhaps) lost’ (Bohn) – it would be better to say that they were, libidinally as well as sonically, anti-Rock.

Or perhaps, as they thought, they were the truth of Rock. Rock divested of all illusions. (The depressive is always confident of one thing: that he is without illusions.)

Accept like a curse an unlucky deal

‘And so here are the extremes of pop: the masking of the world of appearances, and the unmasking.’ - Morley

JD followed Schopenhauer through the curtain of Maya, went outside the Burroughs Garden of Delights, and dared to examine the hideous machineries that produce the world-as-appearance. What did they see there? Only what all depressives, all mystics, always see: the obscene undead twitching of the Will as it seeks to maintain the illusion that this object, the one it is fixated upon NOW, this one, will satisfy it in a way that all other objects thus far have failed to. Joy Division, with an ancient wisdom (‘Ian sounded old, as if he had lived a lifetime in his youth’- Deborah Curtis), a wisdom that is pre-mammalian, pre-multicellular life, pre-organic, saw through all those reproducer ruses. This is the ‘Insight’ that stopped fear in Curtis, the calming despair that subdued any will to want more.

Yet this wisdom brought no enjoyment, obviously. JD saw life as the Poe of ‘The Conqueror Worm’ had seen it, as Ligotti sees it: an automated marionette dance, which ‘Through a circle that ever returneth in/ To the self-same spot’, an ultra-determined chain of events that goes through its motions with remorseless inevitability. You watch the pre-scripted film as if from outside, condemned to watch the reels as they come to a close, brutally taking their time.

A student of mine wrote in an essay recently that they sympathise with Schopenhauer when their football team loses. But the true Schopenhauerian moments are those in which you achieve your goals, perhaps realise your long-cherished heart’s desire --- and feel cheated, empty, no, more – or is it less? – than empty, voided. Joy Division always sounded as if they had experienced one too many of those desolating voidings, so that they could no longer be lured back onto the merry-go-round. They knew that satiation wasn’t succeeded by tristesse, it was itself, immediately, tristesse. Satiation is the point at which you must face the existential revelation that you didn’t want really want what you seemed so desperate to have, that your most urgent desires are only a filthy vitalist trick to keep the show on the road. If you ‘can’t replace the fear or the thrill of the chase’, why stir yourself to pursue yet another empty kill? Why carry on with the charade?

As Scanshifts says, depressive ontology is dangerously seductive because, as the zombie twin of Spinozist dispassionate disengagement, it is half true. As the depressive withdraws from the vacant confections of the Lifeworld, he unwittingly finds himself in concordance with the human condition so painstakingly diagrammed by Spinoza: he sees himself as a serial consumer of empty simulations, a junky hooked on every kind of deadening high, a meat puppet of the passions. The depressive cannot even lay claim to the comforts that a paranoiac can enjoy, since he cannot believe that the strings are being pulled by any One. No flow, no connectivity in the depressive’s nervous system. It is a ‘dry brain’ (Eliot) condition.

The depressive is unable to break through to the other side of this, to see that the analysis of the mechanical causation of your misery is the first step to escaping your Self, and, with it, human OS. So he remains an Outsider who is not yet on the Outside, excluded from the Dominant Operating System, but not capable of making the holes and disused shafts beyond the Symbolic Order liveable, a neurotics, not a psychotic.

The sound from broken homes

Neurosis was Curtis’ art form, just as psychosis was Mark E Smith’s.

Nothing could have been more fitting than that Unknown Pleasures began with a track called ‘Disorder’, for the key to Joy Division was the Ballardian spinal landscape, the connexus linking individual psychopathology with social anomie. The two meanings of breakdown, the two meanings of Depression.

That was how Sumner saw it, anyhow. As he explained to Savage:

‘There was a huge sense of community where we lived. I remember the summer holidays when I was a kid: we would stay up late and play in the street, and 12 o’clock at night there would be old ladies, talking to each other. I guess what happened in the ‘60s was that the council decided that it wasn’t very healthy, and something had to go, and unfortunately it was my neighbourhood that went. We were moved over the river to a towerblock. At the time I thought it was fantastic; now of course I realise it was an absolute disaster.

I’d had a number of other breaks in my life. So when people say about the darkness in Joy Division’s music, by age of 22, I’d had quite a lot of loss in my life. The place where I used to live, where I had my happiest memories, all of that had gone. All that was left was a chemical factory. I realised then that I could never go back to that happiness. So there’s this void.’

Under capitalism, the Social intervenes to make the transition from childhood to ‘the coffin whose name is adulthood’ (Eshun) doubly traumatic. It is not just that you have lost ‘the protection and infancy’s guard’; it is that the whole world of your childhood has been re-developed, bulldozed, reduced to a box full of monochrome photographs. They are rebuilding the city… Yes, always…

Strip-lit, twenty-four hour Kapital grafts the artificial manic-depressive cycle of the economy on top of the ‘natural’ rhythms of the seasons. Kapital is literally extra-Terrestrial, since its crazed veerings from irrational exuberance to irrational dread, from boom to depression bear, no relationship to processes of the Earth.

Dead end lives at the end of the seventies. There were Joy Division, Curtis doing what most working class men still did, early marriage and a kid, the others trapped in the slow, quiet hells in which most of the proletariat endure their working lives.

Feel it closing in

Sumner again: ‘When I left school and got a job, real life came as a terrible shock. My first job was at Salford town hall sticking down envelopes, sending rates out. I was chained in this horrible office: every day, every week, every year, with maybe three weeks holiday a year. The horror enveloped me. SO the music of Joy Division was about the death of optimism, of youth.’

Day in/ Day out

Joy Division connected not just because of what they were, but when they were. Mrs Thatcher just arrived, the long grey winter of Reagonomics on the way, the Cold War still feeding our unconscious with a lifetime’s worth of retina-melting nightmares.

JD were the sound of British culture’s speed comedown, a long slow screaming neural shutdown. Since 1956, when Eden took amphetamines throughout the Suez crisis, through the Pop of the Sixties, which had been kicked off by the Beatles going through the wall on uppers in Hamburg, through Punk, which consumed speed like there was no tomorrow, Britain had been, in every sense, speeding. Speed is a connectivity drug, a drug that made sense of a world in which electronic connections were madly proliferating. But the comedown is vicious.

Massive serotonin depletion.

Energy crash.

Turn on your TV.

Turn down your pulse.

Turn away from it all.

It’s all getting

Too much.

A loaded gun won’t set you free – so you say

Deborah's last picture of Ian Curtis, May 13 1980

‘After pondering over the words to ‘New Dawn Fades’, I broached the subject with Ian, trying to make him confirm that they were only lyrics and bore no resemblance to his true feelings. It was a one-sided conversation. He refused to confirm or die any of the points raised and he walked out of the house. I was left questioning myself instead, but did not feel close enough to anyone else to voice my fears. Would he really have married me knowing that he still intended to kill himself in his early twenties? Why father a child when you have no intention of being there to see it grow up? Had I been so oblivious to his unhappiness that he had been forced to write about it?’ - Touching from a Distance(85)

The great debates over Joy Division – were they fallen angels or ordinary blokes? Were they Fascists? Was Curtis’ suicide inevitable or preventable? – all turn on the relationship between Art and Life.

We should resist the temptation to be Lorelei-lured by either the Aesthete-Romantics (in other words, us, as we were) or the lumpen empiricists. The Aesthetes want the world promised by the sleeves and the sound, a pristine black and white realm unsullied by the grubby compromises and embarrassments of the everyday. The empiricists insist on just the opposite: on rooting the songs back in the quotidian at its least elevated and, most importantly, at its least serious. ‘Ian was a laugh, the band were young lads who liked to get pissed, it was all a bit of fun that got out of hand…’

It’s important to hold onto both of these Joy Divisions – the Joy Division of Pure Art, and the Joy Division who were ‘just a laff’ – at once. For if the truth of Joy Division is that they were Lads, then Joy Division must also be the truth of Laddism.

And so it would appear: beneath all the red-nosed downer-fuelled jollity of the past two decades, mental illness has increased some 70% amongst adolescents. (Just get twenty teenagers in a room and look at their arms if you don’t believe it.) Suicide remains one of the most common sources of death for young males.

A conjecture: if female depression is a response to what they are forced to endure, if, that is to say, it is contingent, then there is something Necessary about male depression, something that goes beyond the circumstantial. The death drive is stronger in the male of the species, the young men with the weight on their shoulders. If testosterone-fed Thanatos cannot slake its death lust in war, it will wage a war on, and in, the Self.

This might explain Joy Division’s enigmatic relationship to Fascism. The Virilio/ Deleuze-Guattari analysis of Fascism, remember, maintains that Fascism is essentially self-destructive: a line of pure abolition. As such, Fascism is just the name for one more variant of the Romantic lust for the Night when all identity, all individuation, is subsumed in ‘an ecstatic aestheticized experience of Community’ (Zizek).

For the Thanatoid Romantic dreamer, life is too much of a mess, a tangle of loose ends that will never tie up. Only in what Zizek, following Kierkegaard, calls the ‘aesthetic suspension of the political’ can Art become Life. That is, Art can only become Life through Death… when the Artist has become one with the frozen tableaux he has created.

‘I crept into my parents’ house without waking anyone and was asleep within seconds of my head touching the pillow. The next sound I heard was ‘This is the end, beautiful friend. This is the end, my only friend, the end. I’ll never look into your eyes again…’ Surprised at hearing the Doors’ ‘The End’, I struggled to rouse myself. Even as I slept I knew it was an unlikely song for Radio One on a Sunday morning. But there was no radio – it was all a dream.’ (Touching From a Distance, 132)

Posted by mark at January 9, 2005 06:33 PM | TrackBack