July 25, 2004

Ian Penman: ‘Technology has made us all ghosts.’

Fredric Jameson: ‘The Jack Nicholson of The Shining is possessed neither by evil as such nor by the "devil" or some analogous occult force, but rather simply by History, by the American past as it has left its sedimented traces in the corridors and dismembered suites of this monumental rabbit warren, which oddly projects its empty formal after-image in the maze outside ‘

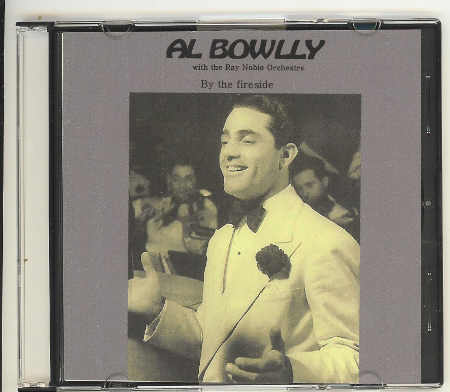

You’ve all heard at least on Al Bowlly song.

The one you’re most likely to know is his version of ‘Midnight, the Stars and You’. revived, appropriately, given that this is a song for which the term ‘haunting’ might have been coined, by Stanley Kubrick in his ‘metageneric ghost story’, The Shining in 1980.

Kubrick in fact utilized the song twice in The Shining; once in the Gold Room party scene, wherein a bewildered Jack Torrance, dressed in a Lumberjacket, stumbles confused amid the revellers in their twenties finery; and then, again, over the famous tracking shot which ends the film on a close-up of the photograph, dated July 1921, from which a tuxedo-wearing Torrance grins out.

If The Shining is a film about the influence of the past on the present - or rather, about the simultaneity of past and present, about the non-chronic, non-sequential time which Deleuze and Guattari call ‘Aeon’ - then Bowlly’s mottled recording was chillingly perfect. He already sounds like a ghost.

Bowlly actually made his most famous recordings a decade after the date of the Overlook party but a decade prior to the technological developments which would allow Frank Sinatra’s records to sound so intimately present. There was still, then, a palpable difference between the recording and the live performance, between presence (which the recording both occludes and preserves) and absence.* So while Sinatra still seems spookily present, uncannily contemporary, the audio equivalent of a sepia haze separates Bowlly from us. Even as you listen to them, his records sound like faded memories.

Like so many of Bowlly’s songs, ‘Midnight, the Stars and You’ is itself about memories, about the attempt to hold onto the haecceity, the hic et nunc, the here and now, even as it is stolen by Time’s passage.

Kubrick used two Bowlly songs in The Shining. The second, ‘It’s All Forgotten Now’, can be heard in the background as Jack speaks in the bathroom with Delbert Grady, ‘the bland and obsequious clean-shaven manservantwhose toneless politeness projects such malevolence through its very inexpressivity’ (Jameson). The irony of the song’s title in this context need hardly be stressed: here is Grady, a man who has murdered his family and then killed himself but who has ‘no recollection of this at all’ (like the father in that dream talked of by Freud and Lacan who, grotesquely, does not know that he is dead). And here is Jack, who, we are informed, has ‘always been the caretaker’ of the hotel but who, similarly, cannot remember being at the Overlook before.

Apart from The Shining, the other context in which you might have encountered Bowlly is of course in Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective and Pennies from Heaven. For Potter, as for Kubrick, Bowlly’s lovely, honeyed croon becomes synonymous with a past that is, paradoxically, forever lost and forever insistent. In other words, Bowlly gives voice to the psychoanalytic past, whose relics, as Freud says, are preserved by being buried.

Kubrick’s selection of Bowlly’s tunes was no doubt inspired by their Englishness and therefore with their association to the past. Yet it’s worth noting that, although Bowlly made his name in London, he was actually born in South Africa. It’s also misleading to atrribute these recordings to Bowlly, since Bowlly, as was par for the course in the thirties, was not so much the main focus of the band as the featured soloist. Most of his major recordings were attributed to the Ray Noble Band, and both Noble and Bowlly - ‘too big for London’ - would ultimately head over to America, where the success of their records had already created an audience for them.

Nevertheless, Bowlly provided the template for a discreetly elegant English pop, a template discarded and all but completely forgotten once rock ‘n’ roll ripped everything up. I’ve written before of my resistance to the claim that pop is essentially adolescent. Yes, Bowlly’s songs are about romance, but it would be to fall into the most crassly reductive cod-Freudianism to assume that romance must always equal sexuality as processed through rock and roll’s unsubtle amplifiers. Bowlly sings from a time before romance was monopolized by the consumer-culture machined desire of the yet-to-be invented teenager. The desire Bowlly’s plaintive warble embodies is no panting passion, but genteel, courtly, cooing. These songs are, genuinely, as seductive as any ever recorded in pop: swoonsomely, insouciantly beguiling rather than sweatily demanding.

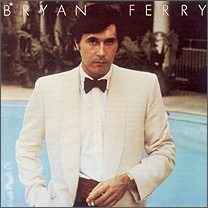

If anyone in English Pop remembers Bowlly, though, it is Bryan Ferry, Ferry who, as Ian Penman so memorably put it, ‘sings as if Rock’s late ‘60s dream of wistful social interference were nothing but an unfortunate lapse in good manners’. When Roxy emerged, all time-scrambled and anachronistic, not so much postmodern as retromodern, or modern retro, they sounded like they could have been the house band in the Overlook . Yet Roxy were more than symptomatic of that incapacity to deal ‘with time and history’ which Jameson identifies of as one of consumer capitalism’s ‘pathologies’. Rather than merely evoking ‘some indefinable nostalgic past, an eternal 1930s... beyond history’, like Kubrick, Roxy interrogated the ‘nostalgia mode’ itself. They were metageneric Pop in the way that The Shining was a metageneric ghost story. In both, Bowlly’s songs of stolen moments and lost time become themselves lost time, a time of authenticity and self-presence now forever gone.

*(It is easy to see why both ghosts. and recording - a ‘science of ghosts’ - should be preoccupations of the deconstructiionists.)

Posted by mark at July 25, 2004 08:42 PM | TrackBack