July 16, 2004

CUSHING'S WHITSTABLE

I went for a daytrip to Whitstable, on the Kent coast, on Friday.

Whitstable is one of those enclaves of carefully ringfenced Englishness, in which Time is not so much frozen or artificially retarded (cf Prince Charles’ grotesquely kitsch retro-Stepfords) aspruned. Developments threatening the ambience are snuffed out or anticipatively warded off. The new is permitted in provided it doesn’t disrupt the existing hamony; thus modern cottages nestle amidst centuries-old counterparts. Since so many of the houses, bisected by the ‘alleys’ that make the town seem like a labyrinth of warrens, are, distinctively, constructed out of wood, Whitstable almost feels like Old New England.

The ocean always brings sublimity to any seaside town. Its inhuman vastness lures and lulls us into meditative revery that we couldn’t explain at the level of the conscious mind. It’s a cellular thing.

Like most seaside places, Whitstable is in an Innsmouthian becoming with the ocean and its creatures. Think of Whitstable and likely as not you think of oysters.

But there is little of the vulgar sublime, the candyfloss neon carny vivacity, of a Skegness or a Blackpool, here. The air smells of fish, not fried onions. Whitstable is discreetly deproletarianized. I had the impression that the families holidaying here were almost exclusively middle class.

But there were, after all, traces of the vulgar sublime in Whitstable on Friday.

Walking along the winding main street, you come across the modest-looking door to the town museum. Inside, there is an exhibition commemorating the life of Whitstable’s most famous resident, Peter Cushing, who died 10 years ago.

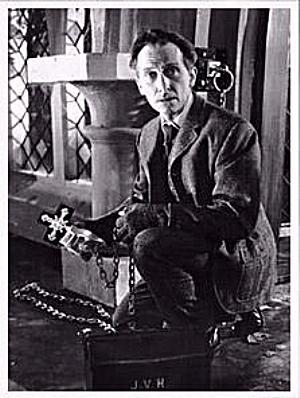

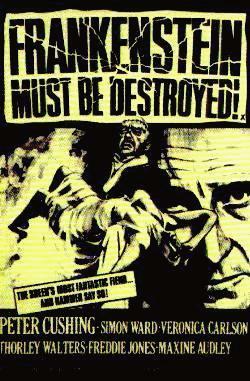

The small exhibition is lovingly curated: film posters, letters from fellow actors such as Lionel Jeffries, Richard Attenborough and Joanna Lumley, examples of Cushing’s model-making, personal effects and photographs are all beautifully displayed.

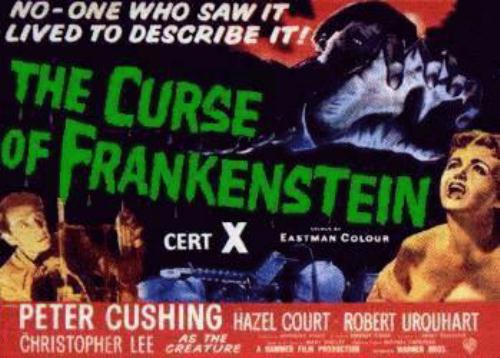

The Hammer film posters – virtually visual defintions of the lurid – point up the contrast between the films for which Cushing was most famous and the sedately retiring town in which he was resident while he made most of them.

Cushing is the kind of actor that has completely disappeared in Britain, along with the British cinema to which he belonged. Genre film is dead here now. In the issue-led, social workerish cineculture that produces Brassed Off and Bend it Like Beckham, everything is pitched at the middlebrow, at the oppressively sensible conscious mind. The unconscious – that ceaselessly productive machine upon which the pulp energies of Hammer fed – goes ignored, and with it the capacity to propagate myth.

Look over Hammer’s filmography, its most significant moments all featuring Cushing, and you see that it was a pulp factory, a hyperfictional production line. Hammer began by reanimating the fiends (Frankentstein’s monster, Dracula) Universal had electro-shocked into cinematic unlife back in the thirties, adding two new ingredients: technicolour and sexuality. (Universal has itself revived those monsters again recently, of course, in Van Helsing. I can only imagine that this was the disappointing travesty everyone said it was, because I couldn’t bring myself to see it). The Quatermass films were of course Hammer’s. (These films and the adapation of Wheatley's The Devil Rides Out - the mesmerically virile Lee as a thinly-disguised Crowley - were perhaps the only notable Hammer films in which Cushing did not feature.)

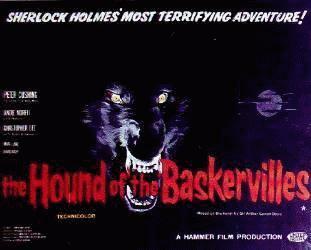

Terrence Fisher remains one of Britain’s most underrated auteurs. He directed Cushing in what is perhaps Hammer’s greatest film, their version of Conan Doyle’s Hound of the Baskervilles, made in the year, 1959, in which Cushing first settled in Whitstable. Fisher’s animistic Dartmoor – all lurking fog and perilous quicksand – is the perfect setting for the ageless battle between Reason and Desire, Civilization and Discontent, that Hammer would play out in endlessly in its version of the Gothic kingdom of the unconscious. Cushing gives the detective an intellect as sharp as his cheekbones, turning in a performance that makes him, for me, the definitive Holmes. The same capacity to embody gaunt rectitude made Cushing almost synonymous with the role of Van Helsing in the Dracula series, where he would play the straightbacked puritan to Christopher Lee’s polymorphously perverse inhuman seducer.

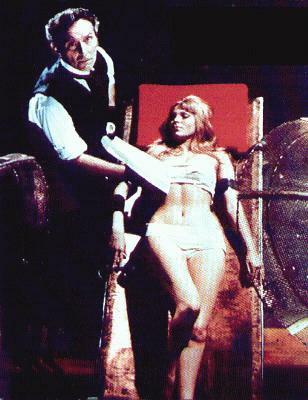

But in the Frankenstein series, it was Cushing’s turn to express a dangerously ambivalent sexuality. The callow, tragic Icarus of Shelley’s novel and the Universal movies – well-intentioned but hubristic - became, in Hammer and Cushing’s hands, an amoral ‘Baron’, marking the shift from nineteenth century Promethean romanticism to a Sixties Sadeianism, wherein Frankenstein’s fervid obsession with uncovering nature’s secrets took on a blatantly erotic dimension.

The most evocative aspect of the exhibition for me was the film posters. These vernacular art works were, famously, often better than the films themselves, occupying that same direct line from the eye to the unconscious as did the paintings on the front of ghost trains. As a child, I would fixate upon the film posters reproduced in my Horror books, constructing in my mind terrors far more vividly nightmarish than those in the movies themselves, which, however good they were, could not but be a disappointment when I saw them years later.

Note to self: must find out more about who produced the Hammer film posters.

Great post, Cushing occupies a special place in my heart. My fave Cushing anecdote is that during those scenes in Starwars where he's commanding plantets to be blown up (shot above the waist), he actualy wearing carpet slippers!

Yeah the Hammer posters are great too, Countess Dracula was always a fave and an alt version of The Mummy poster that has schematics of abilities and murder methods the Mummy employs in the movie, very helpfull.

Thanks Karl!

I forgot he was in Star Wars....

Posted by: mark at July 19, 2004 08:38 AMTop piece!

Mark the most Innsmouthian (?) place Ive ever been is Robin Hoods Bay in N Yorks: tiny little town clinging to the side of a cliff, the 'main' street literally ends in the sea. Full of wretched little lanes up sheer inclines, smokey pubs where you couldnt swing a kitten, weird boarded up houses, dead ends, shops selling only one jar of 'special jam'. At night a mist covers the whole place, hides it from above. You can imagine Dagon rising there. If ur ever oop north visit there sure u'd write a great piece about it.

Posted by: Baal at July 19, 2004 06:28 PMThat's near Whitby, isn't it?

Whitstable actually reminded of a Southern Whitby...

Posted by: mark at July 19, 2004 08:56 PMYes...just maybe 4 miles down the coast. On a sunny day its like that awful Heartbeat (filmed in nearby Goathlands actually) crossed with The Prisoner, with extras from Straw Dogs for company.

Posted by: Baals at July 19, 2004 09:13 PM