January 25, 2004

THE NEW YORK PRESS OFFCUTS

On the principle of waste not, want not, I've pasted some material below that was originally intended for New York Press. Apologies to Marcus from Rephlex, who sent me the review copies - I did try my best to get the Rephlex reviews placed. I've also included a piece I wrote for NYP on the Junior Boys - it'll be old news to most of youse lot, but it's probably worth an airing.

Cybotnia: Cybotnia

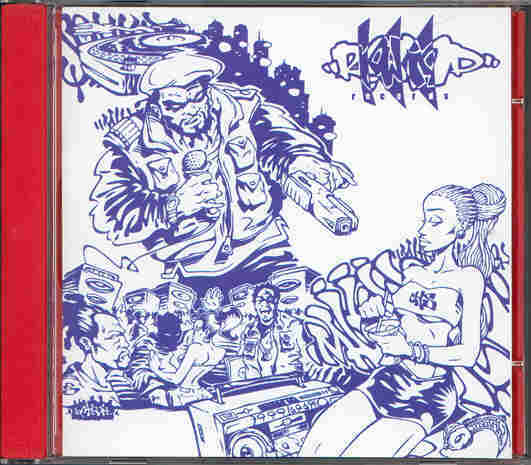

Rewind Records Soundmurderer and SK1

Pangeia Instrumentos: Victor Gama

Three releases showcasing the diversity of London’s maverick label, Rephlex.

The 8-track ep ‘Cybotnia’ is a collaboration between Cylob (aka longtime Rephlex artist Chris Jeffs) and Astrobotnia (aka Finnish ‘laptop dreamer’ Alekis Perala). Initial impressions of a somewhat forbidding glitched abstract techno give way, on subsequent listens, to a growing appreciation of the duo’s command of texture and mood control. Jeffs and Perala’s digital pallet of electronic moans, groans, squiggles, bleeps and ominous synths is offset by gently reverbed gongs and bells in what makes me think, on occasions, of a laptop update of Can’s ‘Peking O’ or Japan’s Tin Drum. Like all the best electronic music, ‘Cybotnia’ sounds less like something painstakingly programmed than a riotously luminescent audio unlifeform, undulating, pulsating and mutating according to its own alien logic.

Soundmurderer is the alias of Todd Osborn, the owner of Detroit’s first Drum and Bass record store; SK1 is one of the aliases of Ann Arbor’s Tadd Mullinx, a man who has produced instrumental hip hop under a variety of pseudonyms (including Dabyre, on Prefuse 73’s Eastern Developments label). Their joint LP (released in association with Osborn’s fittingly-named Rewind label) is very much an enthusiast’s record. It lovingly revisits the British ‘jump-up’ jungle sound of a decade ago: a genre which consisted almost solely of Jamaican MC ragga chat riding atop digital mash-ups of the ‘Amen’ breakbeat (so named because it is sampled from funksters the Winstons’ track, ‘Amen, Brother’). If that sounds limited, it actually wasn’t: jump-up jungle made astonishingly imaginative use of its few resources, and while history has been somewhat unkind to the then more critically-feted ‘artcore’ genre, jump-up jungle’s libidinal brutalism still sounds fresh. Which is presumably why producers have been drawn back to it recently. Fellow Rephlex artist Luke Vibert is another currently mining a similar seam , on his five ep series, ‘Amen Andrews’. But where Vibert imagines an alternative past in which jump-up jungle is combined with techno, Soundmurderer and SK’s approach is strangely curatorial. In a sonic equivalent of Gus Van Sant’s scene-by-scene remake of Hitchcock’s Psycho, the tracks seem to have been conceived of as near-exact simulations of the original jump-up sound, so much so that they could comfortably have been fitted into a DJ set in 1994. Even when they sample a rap source (Public Enemy’s ‘Mi Uzi Weighs a Ton’) it is from a pre 94-track. The whole effect is strangely disconcerting: as if a part of Britain’s mid-90’s (multi) culture has been wholesale preserved and re-animated in the USA in 2003.

In every way different is Victor Gama’s ‘Pangelos Instrumentos’. If Soundmurderer and SK1 recreate the near-past, Gama aims to establish a continuity between the ancient past and the present. Gama, an Angolan of Portuguese origin, produces his sounds on acoustic devices he has designed as ‘evolved’ versions of traditional African instruments. These strange machines – so oddly beautiful that they have been exhibited as sculptures – produce a hauntingly desolate sound, simultaneously harmonic and percussive. Gama’s deceptively simple, intricate involutions can sound like Steve Reich played on a ribcage; or junkyard symphonies played on glass; or chimes gently agitated by a playful wind; or automata learning to make music by beating their own mechanoid spines. (I’m reminded of the apartment of the android tinkerer, Sebastian, in Blade Runner.) Yet what breathes through all these compositions is the silence and space of desert(ed) terrains, landscapes populated by no-one but traversed by nomads; geographies beyond ordinary human time…

Richard X Presents the X-Factor Volume 1

‘We’re looking for the X-factor.’

- Line endlessly repeated by judges on the UK’s Pop Idol/ Popstars

Is Richard X a symptom of Pop’s current malady, or a potential cure?

With its hired-hand reality TV star guest vocalists, fruit machine bleeps, simulated adverts and omnipresent, ominous sense of ubiquitous commodification (‘everything is for sale – even this!’), Richard X presents his X-Factor is a distorting funhouse mirror of UK Pop 2003. But step through the mirror and you enter an alternate Pop universe of which X is the mad scientist x-perimenter-God.

XYZ not r ‘n’ r.

The Year Zero of X’s Popverse is something like ‘our’ 1979. X’s No rock and roll in X’s Pop anti-history, which begins with the synthesizer, and ends – or loops back on itself – before ‘our’ Pop universe rehabilitated guitar-n-r and the future ended. X’s is a postmodern Modernism, a revival of Synthpop’s disdain for rock nostalgia.

You will be familiar with X’s trademark technique from last year’s smash, ‘Freak Like Me’, in which the Sugababes sang Adina Howard over Tubeway Army’s ‘Are “Friends” Electric?’ Dr X repeats the same trick – splicing black r ‘n’ b with white electro - on Liberty X’s ‘Being Nobody’ (a Human League-Chaka Khan hybrid) and on Kelis’s ‘’Finest Dreams’ (Human League again, plus SOS Band). Yet on the album this seems to be less a gimmick than a formula for a Pop Utopia, or Utempia, in which Pop is racially – and temporally – desegregated. X engineers a Pop present in which Soul and Synths are (un)natural bedfellows. The template, oddly enough, might have been the early Spandau Ballet. Back in 1981, Spandau were soul boys turned leaders of the New Romantic scene, and it’s no surprise to hear their ‘’Chant Number 1’ getting the X treatment on ‘Rock Jacket’. Like the whole New Romantic clique, Spandau were Art Pop, and it is Art Pop that X-Factor dreams of digitally restarting. Art Pop was meta-Pop, and so is X Factor: a self-conscious reflection on 00’s Pop and its status as commodity. ‘Has Richard X sold out?’ asks a ‘meaningless market research’ survey on the CD booklet, in an echo of The Who Sell Out, a previous landmark in Art Pop.

Nothing new? Nothing now? The nullity of a ringtone Pop well past its sell-by date?

Yes or no?

Or X for unknown?

THE JUNIOR BOYS: HAIL THE NEUROMANTICS

It’s strange, isn’t it, how synthpop is so associated with a certain era?

Rock sounds and riffs are invariably allowed to ascend to some timeless place, beyond the vagaries of fashion, but dare to invoke synthpop’s textures, and you’ll be labeled retro quicker than you can say ‘Moog’ . Sometimes the accusation is justified: the Electroclash scene, or – an even more extreme example - Detroit’s Adult, display a forger’s obsessiveness, a fan’s desire to reanimate, wholesale, a particular moment, sometime in 1980… All of which confirms that nothing dates quite so quickly as Yesterdays’ Future.

And just a few years ago, nothing was more embarrassing than synthpop. We’re indebted to Kodwo Eshun’s study of ‘sonic fiction’, More Brilliant Than the Sun, for effecting a complete re-evaluation of the genre. Eshun’s tracking of the ur-sources of hip-hop, techno, house and jungle took him far beyond the usual suspect, Kraftwerk – who already enjoyed more or less universal respect – and down into the bargain bin depths of the apparently unredeemable and the laughable: Gary Numan, Visage and A Flock of Seagulls. Their rep as no-hopers, Eshun showed, was limited to White Rock(ism): in Techno Detroit and hip hop New York, the synthpoppers were revered as pioneers of electronic music. (Anyone who doubts this should check out Kurtis Mantronik’s 2002 compilation on London’s Soul Jazz records, ‘That’s My Beat.’ The LP – a collection of the tunes that inspired Mantronik when they were played in the New York clubs of the early eighties - includes Visage, Yello, YMO, and Sakamoto.)

What happened along the way, as synthpop begat Mayday and Underground Resistance, was that the synth got severed from the Pop. The Song got lost as the Track got built.

All of that changes with the Junior Boys, whose debut EP, ‘Birthday/ ‘Last Exit’ is released in September on London’s kin records. The Junior Boys – who are actually just one boy, Jeremy Greenspan - hail from Hamilton, Ontario, and there’s a pleasing symmetry in the fact that the Junior Boys’ material is to come out on a London label. Detroit’s infatuation with synthpop brought with it an attendant anglophilia (check all those simulated English accents on the early Model 500 records!), so there’s something of a closing of a cycle here. North America returns synthpop to its home, changed and renewed.

Renewal is the key. While the Junior Boys retain synthpop’s modernism, its intolerance for the old (something that Techno built a genre upon) what they also recover is something that is often forgotten about synthpop: its melancholia. Synthpop is usually remembered as death-of-affect emotionless, Terminator cold. Yet that very coldness often had a keening, plangent quality, an impersonal sadness, as if the machines themselves were weeping. The Junior Boys have obviously absorbed Numan and Foxx, but it is OMD who come to mind most when listening to ‘Birthday’ and ‘Last Exit.’ These delicate, vulnerable songs recall the yearning swoon of something like OMD’s ‘Souvenir.’

Yet there is no trace of revivalism here. In fact, it is just as easy to fit the Junior Boys into another trajectory altogether. Five years ago, the manic X-tasy rush of Speed Garage slowed down as it became acquainted with Timbaland’s R and B. The result was 2-step, an itchy and scratchy, edgy, dance music in which voice and song once again became central, albeit subjected to sampler-micro-splicing reconstruction and recombination. London’s Garage scene has taken another turn, into the brutalist rap of the so-called Grime scene. The Junior Boys’ rhythms – tripping and stuttering in that addictive tic-time Timbaland discovered – are a continuation of the prematurely curtailed 2-step experiment.

In combining 2-step with synthpop – a crude and mechanical description of their beguiling sonic sorcery, which could just as easily be compared to Steely Dan or Scritti Politti - the Junior Boys have mapped out a future for white pop. They have resisted the temptation either to ignore black music – never on the cards in their case – or to redundantly ape it. Instead, they have produced a new white pop template that acknowledges and absorbs black influence, but has the confidence to – literally – speak in its own voice. The Junior Boys’ vocals – vulnerable, quiet, quavering, wavering with longing – are their special treasure. Both ‘Birthday’ and ‘Last Exit’ are intimated in Jeremy’s emaciated, late-late night swooncroon, the sound of a dream voice, a dreamed voice… And make no mistake: this is pop music; there is a subtly compulsive hook in almost every line.

The term ‘neuromantic’ is being applied to Junior Boys and, in its suggestion of Gibsonesque edgy-tech plus synthpop plus emotional ravishment, it’s perfect. The sound of a renewed future….

Re: merging soul and synthpop, this was early Soft Cell's MO also (much more successfully than Spandau Ballet IMHO.) This is a big reason electroclash sounded so much worse than what its hype suggested; they forgot the soul behind the sleaze.

Posted by: anode at January 29, 2004 04:43 AM